2. Grandparents in their young grandchildren's lives

2. Grandparents in their young grandchildren's lives

Jennifer Baxter and Diana Warren

2.1 Introduction

Grandparents play a vital role in many families, being an important source of support to parents and enriching children's lives through a wider family network. This has been highlighted in research on grandparenting and intergenerational relationships for families in Australia (Brennan et al., 2013; Gray, Misson, & Hayes, 2005; Horsfall & Dempsey, 2011, 2013; Jenkins, 2010; Ochiltree, 2006; Weston & Moloney, 2014; Weston & Qu, 2009) and overseas (e.g., Barnett, Scaramella, Neppl, Ontai, & Conger, 2010; Fergusson, Maughan, & Golding, 2008; Griggs, Tan, Buchanan, Attar‐Schwartz, & Flouri, 2010; Mueller & Elder, 2003; Pebley & Rudkin, 1999; Tan, Buchanan, Flouri, Attar-Schwartz, & Griggs, 2010). This chapter uses LSAC to explore different ways that grandparents are involved in the lives of the LSAC children, capturing involvement from ages 0-1 years through to 12-13 years. It extends and updates previous LSAC research about grandparents (Gray et al., 2005).

Grandparent involvement may take different forms, such as grandparents sharing a residence with children, providing child care or otherwise having contact with grandchildren. This chapter describes these different forms of grandparent involvement. Comparisons across different family forms and children of different ages highlight the variable and changing nature of grandparent involvement across children's lives. These analyses are from the perspective of the LSAC children and family, and so report on children's possible involvement with any of the child's grandparents. This is a different perspective than that of grandparents themselves about their involvement with grandchildren.

Firstly, information on the household structure of LSAC children is used to identify the incidence of children having co-resident grandparents, and the characteristics of those grandparents and families. Gray et al. (2005) found that in Wave 1, 7% of the infants and 4% of the 4-5 year olds were living in the same household as a grandparent. While these numbers are quite small, previous research has shown that co-resident grandparents can make significant contributions to family life, especially to the financial circumstances of single-mother families (Mutchler & Baker, 2009). In fact, Gray et al. (2005) reported that in the infant cohort of LSAC in Wave 1, of children who had a parent living elsewhere from their primary parent's residence, almost one in four had a co-resident grandparent.1 Exploring the characteristics of co-resident grandparents (such as their age and health status), along with family characteristics, can provide some insights on the ways in which family life (in terms of child care arrangements and the amount of contact that children have with their grandparents) is different in these families compared to others. Information on financial wellbeing and sources of support provide some new insights about the functioning of grandparent co-resident families compared to others. The focus is on grandparents who are co-resident as part of a three-generation household, and does not cover grandparents who have primary care for grandchildren, since they are insufficiently represented in LSAC. For more information about these families refer to Brennan et al. (2013) and Weston and Moloney (2014).

This chapter also covers grandparents as child care providers. In Australia, grandparents are a key source of child care, especially when children are very young and when mothers are employed (Baxter, 2013; Jenkins, 2010), just as is the case in other countries such as the United States (Baydar & Brooks-Gunn, 1998). Australian research has highlighted the significance of grandparent care (Baxter, 2013, 2014; Baxter, Gray, Alexander, Strazdins, & Bittman, 2007; Gray et al., 2005; Hand & Baxter, 2013; Horsfall & Dempsey, 2011, 2013; Weston & Qu, 2009) and this chapter expands on this, to explore how grandparent care is used in conjunction with other forms of care across different families and as children grow, and to describe the characteristics of grandparent-provided child care.

As noted by Mutchler and Baker (2009) "caring 'from a distance' is characteristic of many grandparents whose roles may be defined in terms of affection and attachment but little day-to-day interaction" (p. 1577). The final aim of this chapter, then, is to include analyses of grandparent contact with grandchildren, to capture this form of grandparenting. Based on grandparents' reports, a significant proportion see their grandchild frequently. Horsfall and Dempsey (2011) reported that about three in four see their grandchild at least once a month. Gray et al. (2005) presented similar figures from children's perspectives, using Wave 1 of LSAC, in reporting on the proportion having at least monthly face-to-face contact with grandparents. Differences in contact are explored for maternal versus paternal grandparents as children grow and across different family forms. Exploring this for children growing up primarily in households headed by a single parent is especially useful as parental separation has previously been shown to potentially alter grandparents' involvement with grandchildren (Gray et al., 2005; Weston & Qu, 2009).

The key research questions explored in this chapter are:

- What are the characteristics of grandparents living with the LSAC children, and of the families in which they live?

- What is the nature of grandparent-provided child care, in terms of hours per week, days per week and purpose?

- How much contact do children have with their grandparents?

- How does grandparent-provided child care and grandparent-contact change as children grow?

- What family characteristics explain variations in different aspects of grandparent involvement?

2.2 Data and method

Data from both cohorts and five waves are explored in this chapter, to provide insights on grandparents' presence and involvement as children grow. Throughout these analyses, we have excluded children being raised by grandparents, identified as families in which a grandparent was the child's primary carer. This resulted in the exclusion of between 13 and 19 cases each wave when the B and K cohorts were pooled, and was done because the number of families in this situation is too few to be able to produce reliable estimates of such families' circumstances.

Three key sets of information are used in this chapter: one on grandparent co-residence, another on grandparents as child care providers, and another on children's contact with grandparents.

- Details about children's household structure were used to provide information about the co-residence of grandparents, on grandparents' relationships with resident parents and other characteristics.

- Details about the types of child care used by children were examined to determine to what extent grandparents provide child care, and how that care is contextualised with other forms of care across the ages of children in the B and K cohorts. Most of this information is as reported by the child's primary carer in the main interview.

- Finally, information on the frequency of contact between children and grandparents is analysed. This information is largely sourced from the primary carer's self-completion surveys.

The above data are examined by age of child throughout the chapter with some other comparisons made according to children's family characteristics. A key characteristic is whether children are living with couple parents or a single parent.2 Most single parents were single mothers (95% across both cohorts and five waves), but single fathers are included also. Because of the small number of single fathers we do not make the distinction between single mothers and fathers even though grandparent involvement (and whether maternal or paternal) is likely to vary depending on whether children live with their mother or their father. While this classification, therefore, does not capture the full complexity of family relationships that might affect grandparental involvement, it provides some first insights.3

Other data items are introduced within each of the sections. For example, in exploring grandparental child care, parents' employment status is included, given the strong associations between maternal employment and child care use. We report on associations between family characteristics or primary carer characteristics and grandparent involvement. Almost all the primary carers are mothers (95% in single-parent families and 97% in couple families, across both cohorts and all waves), but a focus on primary carer (rather than maternal) characteristics allows father primary-carer families to be included in the analyses.

The analyses explore different roles of grandmothers and grandfathers, and maternal and paternal grandparents where data permit. Specifically:

- In the analyses of grandparents, grandparents could be identified as maternal or paternal grandmothers or grandmothers through their relationship to the study child and their relationship to parents in the household. Even in single-parent households, it was possible to identify whether a co-resident grandparent was maternal or paternal.4 A very small number of co-resident great-grandparents of study children were counted as if they were grandparents. Grandparents who were visitors or temporary household members were not counted.

- For the analyses of grandparent-provided child care, details were not captured of whether care was specifically provided by grandmothers or by grandfathers, but (from Wave 2) was captured as care provided by maternal or paternal grandparents (or both).

- For the analyses of children's contact with grandparents, from Wave 2, information could be derived about contact with maternal or paternal grandparents, with some limitations that are discussed in that section concerning the incomplete information for single-parent families. Information is not collected separately in respect to grandmothers and grandfathers.

It was not possible to determine whether children actually had, at the times of data collection, living maternal or paternal grandmothers or grandfathers. It would of course be expected that as children grow older they would be less likely to have grandparents still living, and those living may be less accessible to grandchildren due to heightened frailty or health problems. Changes in grandparent involvement by child age may be a consequence of such changes. But also, given that fathers are on average older than mothers, such age differences might translate into children having older (or not living) paternal grandparents compared to maternal grandparents, and having older (or not living) grandfathers compared to grandmothers. These differences are likely to in part explain any observed differences between these grandparents' involvement with children. For example, for mothers in couple families in Wave 5 of the K cohort, the median birth years of their mothers was 1942 and of their fathers was 1939. For fathers, the median birth years of their mothers was 1939 and of their fathers was 1936. Within these families at Wave 5, when asked about children's contact with grandparents, it was reported that 7% of children had no maternal grandparents and 10% had no paternal grandparents, and the birth year of grandparents in these families was earlier than that reported for other families. In analysing children's contact with grandparents in section 1.5, we report how these figures changed over the waves of LSAC.

More detailed information about the data used is presented within each of the sections that follow.

2.3 Co-resident grandparents - incidence and characteristics

This section looks at co-resident grandparents; that is, grandparents who reside with the LSAC study child and either one or both parents of this child. These families are also sometimes described as three-generation families (Dunifon, Ziol-Guest, & Kopko, 2014; Pilkauskas & Martinson, 2014), and are distinct from custodial or "skipped generation" grandparent families, in which the children's parent/s are not resident within the household.5

In Wave 1 of LSAC, 7% of the infants and 4% of the 4-5 year olds were living with a grandparent. Table 2.1 shows the percentage of children who had a co-resident grandparent remained at around these levels across the five waves of the study for the B and K cohorts. Across all waves and the two cohorts combined, this equates to an overall average of 5% living with a grandparent. This is somewhat lower than the 8% of children reported to be living with grandparents in three-generation households in the US in 2012 (Dunifon et al., 2014).

| Grandparental presence | 0-1 year (%) | 2-3 years (%) | 4-5 years (%) | 6-7 years (%) | 8-9 years (%) | 10-11 years (%) | 12-13 years (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B cohort | |||||||

| Grandparent present | 6.6 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 5.1 | 4.4 | ||

| Grandmother only present | 2.4 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 2.1 | ||

| Grandfather only present | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.6 | ||

| Grandmother and grandfather present | 3.6 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 1.7 | ||

| Grandmother present a | 6.0 | 5.2 | 4.5 | 4.2 | 3.8 | ||

| Maternal grandmother | 4.1 | 3.9 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 2.6 | ||

| Paternal grandmother | 1.8 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.3 | ||

| Grandfather present a | 4.2 | 3.8 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 2.3 | ||

| Maternal grandfather | 2.8 | 3.0 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.6 | ||

| Paternal grandfather | 1.4 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | ||

| No. of observations | 5,101 | 4,600 | 4,331 | 4,239 | 4,071 | ||

| K cohort | |||||||

| Grandparent present | 4.3 | 4.7 | 5.4 | 4.6 | 4.6 | ||

| Grandmother only present | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 2.6 | ||

| Grandfather only present | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.7 | ||

| Grandmother and grandfather present | 1.6 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 1.4 | ||

| Grandmother present a | 3.8 | 4.1 | 4.5 | 3.8 | 4.1 | ||

| Maternal grandmother | 2.7 | 3.0 | 3.5 | 2.9 | 3.0 | ||

| Paternal grandmother | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.2 | ||

| Grandfather present a | 2.1 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 2.1 | ||

| Maternal grandfather | 1.5 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.6 | ||

| Paternal grandfather | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.4# | 0.5# | ||

| No. of observations | 4,971 | 4,451 | 4,284 | 4,159 | 3,940 | ||

Notes: Percentages in the maternal and paternal rows do not totally add up to the total grandparent present row, as a very small number of grandparents were not identified as either maternal or paternal grandparents (< 1%). a These percentages include those with grandmother present as well as grandfather present. # Relative Standard Error > 25%. Percentages may not sum exactly to the subtotals due to rounding.

Source: B and K cohorts, Waves 1 to 5

Other information about co-resident grandparents is summarised in Table 2.1:

- The percentage of LSAC children who lived with a grandparent was higher at younger ages, with the percentage living with a grandparent highest at age 0-1 year (7%) and 2-3 years (6%) compared to older ages (varying between 4% and 5%).

- Children were more likely to be living with a grandmother than with a grandfather across all ages, although the patterns by child age were consistent for grandmother and grandfather co-residence.

- When children lived with a grandfather, they usually also had a grandmother co-resident, such that children lived with both grandparents. It was rare for children to be living with a grandfather without a grandmother also present, when compared to living with only a grandmother.

Analyses of these data longitudinally show that the presence of a co-resident grandparent is not very stable, a finding that has been observed elsewhere (Pilkauskas & Martinson, 2014). Overall, across five waves of LSAC, 13% of children in the B cohort (covering 0-1 year through to 8-9 years) and 10% in the K cohort (covering 4-5 years through to 12-13 years) had a grandparent present for at least one of the five waves. In the B cohort, this included 9% with a grandparent co-resident at one or two waves only, 3% for three or four waves and 1% for five waves. In the K cohort, this included 7% with a grandparent co-resident at one or two waves only, 2% for three or four waves and 2% for five waves.

Information about grandparent co-presence is disaggregated in Table 2.1 to show how children's grandparents were related to the children's mother or father. That is, if the grandparents were the parents of the child's mother they were classified as maternal grandparents, and if parents of the child's father, they were classified as paternal grandparents. Overall, it was more likely that co-resident grandparents were maternal grandparents rather than paternal grandparents. This applied to grandmothers as well as grandfathers.

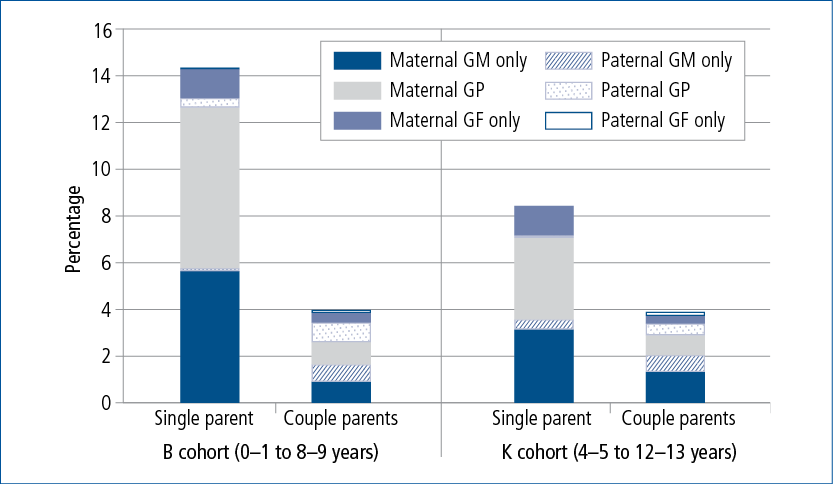

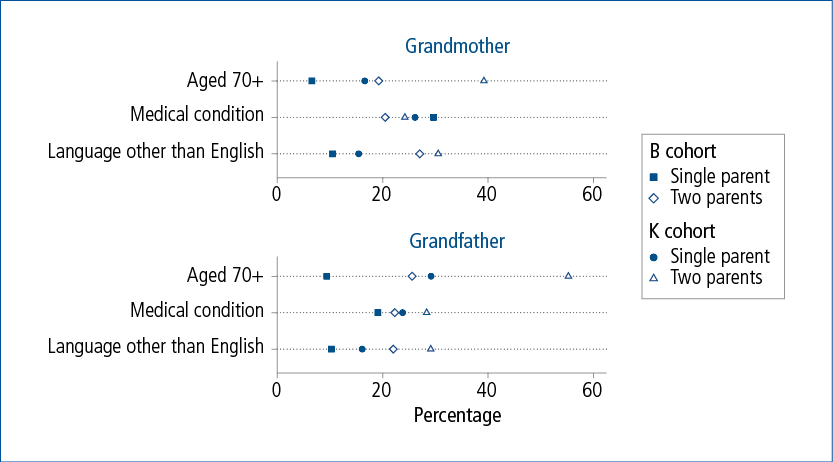

The higher incidence of the co-presence of maternal, rather than paternal, grandparents largely reflected that in single-parent households, the majority of grandparental co-residence involved maternal grandparents, either as the maternal grandmother alone or both maternal grandparents (Figure 2.1). Within two-parent families there was more diversity of co-resident grandparental relationship types.

Table 2.1 shows that among 0-1 year olds (Wave 1 of the B cohort) one in four children living in a single-parent household had a co-resident grandparent. This percentage declined over later waves for this cohort, as seen in the percentage of children in single-parent households who have a co-resident grandparent in Chapter 3 of this volume (the percentage declined from 24% to 8% over the five waves). However, even averaged over five waves (from 0-1 through to 8-9 years), the percentage living with a grandparent was higher in single-parent households than in other household forms. This is indicated in Figure 2.1, with the height of the bars being the percentage of children living with a grandparent within each household type.

The difference between single-parent and couple-parent households was also apparent among somewhat older children (in the K cohort), although was less marked than at the younger ages of children in the B cohort.

While it was uncommon for children to have a co-resident grandparent, selection into this household form may be more likely when parents have a greater need for help or support (financial or otherwise) (Dunifon et al., 2014; Pebley & Rudkin, 1999; Pilkauskas & Martinson, 2014). Parents' age, educational attainment and employment status are included here to explore this, as they capture different aspects of socio-economic status. Also, as families from certain cultures are more likely than others to live in extended family forms, parents' language spoken at home is explored as an indicator of cultural differences. To capture possible regional variation in grandparent co-residence, we explore differences according to remoteness. Table 2.2 shows that at Wave 1, some parental characteristics were associated with a higher likelihood of having a co-resident grandparent:6

- Consistent with the earlier analyses, having a co-resident grandparent was significantly more likely in single-parent households.

- When the child's primary carer was relatively young, families were significantly more likely to have a co-resident grandparent, and this was especially marked in the younger cohort.

- Differences according to the primary carer's educational attainment were less marked, although those with lower educational attainment were more likely to have a co-resident grandparent than those with higher educational attainment.

- A family-level variable that identified whether or not both (or single) parents were employed was not significantly associated with grandparent co-residence for 4-5 year olds (K cohort, Wave 1), but for 0-1 year olds (B cohort, Wave 1) grandparent co-residence was less likely when all parents in the household (whether one or two) were employed.

- Having a co-resident grandparent was more likely when one of the parents mainly spoke a language other than English at home. (Other analyses of grandparent characteristics (not shown) reveal that in many of these families, the grandparent mainly spoke a language other than English also.)

- Only small differences were apparent according to an area-level classification of the remoteness of residence (only 4-5 year olds).

Figure 2.1: Co-resident maternal and paternal grandmothers and grandfathers by household type

Notes: GM = grandmother: GF= grandfather; GP = grandparents, i.e., both grandmother and grandfather. Most single parents are single mothers (95% across the sample). Two-parent families include two-biological parent families as well as those with one or two non-biological parents.

Source: B and K cohorts, pooled Waves 1 to 5

As noted previously, grandparental co-residence may be explained by a number of circumstances. It may be to provide some support or assistance to the grandparent. It may simply be to allow for family members to spend time together and develop relationships. It may also be to allow grandparents to provide some support to the children and parents, especially to provide assistance with housing or financial support for a time. Existing research reveals that the formation of multigenerational households, such as is formed through grandparent co-residence, is usually done to address the needs of the younger generation, as reflected in the last of these reasons (see Mutchler & Baker, 2009 for related literature). Not surprisingly, research has shown that single parents are particularly advantaged when living in a multigenerational household, such that single parents living with grandparents have significantly better financial circumstances compared to those living alone (Mutchler & Baker, 2009). This reflects that pooling living costs, or pooling or access to the grandparents' resources (housing and other) may improve the economic circumstances of families who would otherwise be faced with difficult financial circumstances.

Reasons for co-residence of grandparents are not collected in LSAC, and so we cannot determine whether co-residence is primarily for the benefit of the grandparent/s or for the rest of the family. However, information about parents' housing tenure provides insights, especially in the identification of parents who are living rent-free, who are likely to be living in the grandparents' home.

| Children aged 0-1 year (B cohort) | Children aged 4-5 years (K cohort) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selected characteristics | Has co-resident grandparent (%) | No co-resident grandparent (%) | Total (%) | Has co-resident grandparent (%) |

No co-resident grandparent (%) | Total (%) |

| Family composition | ||||||

| Single parent | 24.2 | 75.8 | 100.0 *** | 8.6 | 91.4 | 100.0 *** |

| Couple parents | 4.6 | 95.5 | 100.0 | 3.5 | 96.5 | 100.0 |

| Primary carer age at child's birth (years) a | ||||||

| 15 to 24 | 19.8 | 80.2 | 100.0 *** | 6.6 | 93.4 | 100.0 ** |

| 25 to 34 | 5.1 | 94.9 | 100.0 | 4.3 | 95.7 | 100.0 |

| 35 and over | 2.7 | 97.3 | 100.0 | 2.9 | 97.1 | 100.0 |

| Primary carer education | ||||||

| Incomplete secondary only | 12.6 | 87.4 | 100.0 *** | 6.8 | 93.2 | 100.0 *** |

| Secondary, certificate or diploma | 7.6 | 92.4 | 100.0 | 4.2 | 95.8 | 100.0 |

| Bachelor degree or higher | 3.7 | 96.3 | 100.0 | 3.3 | 96.7 | 100.0 |

| Employment status | ||||||

| Both parents (or single parent) employed | 5.1 | 94.9 | 100.0 ** | 4.3 | 95.7 | 100.0 |

| One (or both) parents not employed | 7.9 | 92.1 | 100.0 | 4.2 | 95.8 | 100.0 |

| Main language spoken at home | ||||||

| Both (or single parent) mainly speaks English | 5.5 | 94.5 | 100.0 *** | 3.2 | 96.8 | 100.0 *** |

| One (or both) parents mainly speaks a language other than English at home | 12.2 | 87.8 | 100.0 | 9.3 | 90.7 | 100.0 |

| Region | ||||||

| Major city area | 7.2 | 92.8 | 100.0 | 4.8 | 95.2 | 100.0 * |

| Inner regional | 5.2 | 94.8 | 100.0 | 3.3 | 96.7 | 100.0 |

| Outer regional or remote b | 5.7 | 94.3 | 100.0 | 3.1 | 96.9 | 100.0 |

| All families | 6.6 | 93.4 | 100.0 | 4.3 | 95.7 | 100.0 |

Notes: Significance (chi-square) tests used to compare proportions with, without co-resident grandparents. a This is derived from parent age and child age at Wave 1. b Some LSAC families live in remote areas but LSAC is not representative of families living in remote areas. *** p < .001; ** p < .01; * p < .05. Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Source: B and K cohorts, Wave 1

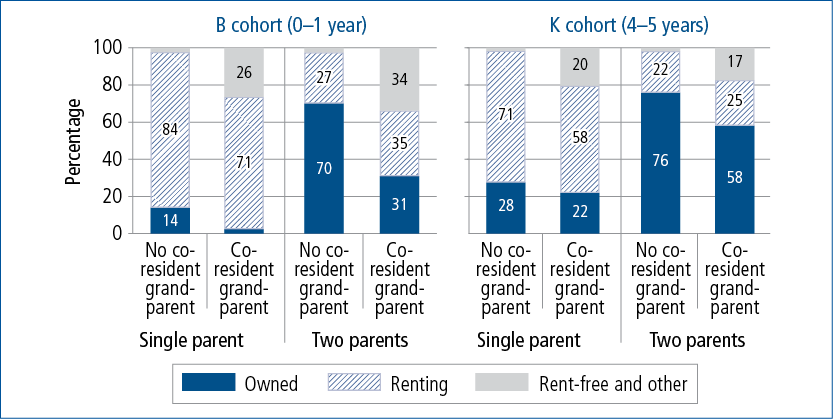

Figure 2.2 shows the parent-reported housing tenure at Wave 1 for families with and without a co-resident grandparent, also classifying families by cohort and parental relationship status. The category of most interest is that of "living rent-free or other", which captured a significantly larger proportion in the grandparent co-resident households. The findings suggest that within families who are co-resident with grandparents, approximately one fifth to one third (varying across groups) were possibly living in the grandparents' home, with no or very low housing costs. Parents in these grandparent co-resident households were also less likely to be home owners or purchasers compared to those who were not, suggesting a degree of socio-economic disadvantage associated with the incidence of grandparent co-residence, at least for some families. However, within two-parent households of 4-5 year olds a large proportion with co-resident grandparents owned or were purchasing their own home. Together, this information suggests considerable heterogeneity in the grandparent co-residence group.

Without also having information about co-resident grandparents' own housing tenure, we are somewhat limited in our being able to explain the housing circumstances within co-resident grandparent families. Nevertheless, in future analyses of these data it may be useful to consider how tenure intersects with grandparent co-residence in different regional areas (such as remoteness or socio-economic disadvantage) and in families with different characteristics (such as parental education or employment).

Figure 2.2: Housing tenure of LSAC children's parents, by grandparental co-residence, household type and cohort, Wave 1

Notes: Owned includes "being paid off by you and/or your partner" or "owned outright by you and/or your partner". Renting is "rented or boarded at by you and/or your partner" plus small numbers who reported tenure of "being purchased under a rent/buy scheme" and "occupied under a life tenure scheme". Rent-free and other includes "live here rent free" (86% of cases) and "none of these" (14%).

Source: B and K cohorts, Wave 1

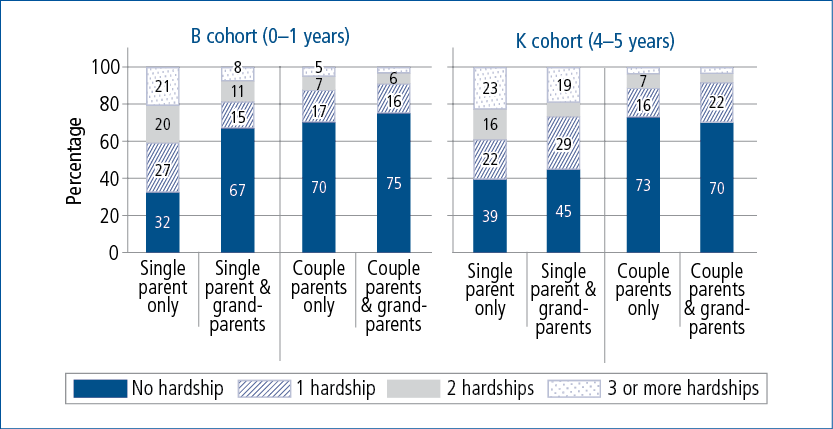

As noted above, a consequence of, and perhaps a motivation for, grandparental co-residence may be that parents are able to avoid certain financial hardships, through sharing of resources or being able to draw upon the resources of the grandparent. This was explored, using LSAC, by counting how many of a list of financial hardships each family reported experiencing in the previous year. These hardships were having gone without meals, been unable to heat or cool their home, having had to pawn or sell something, being unable to pay the mortgage or rent on time, having sought assistance from a welfare or community organisation, having been unable to pay bills on time.7 Figure 2.3 shows the distribution of number of hardships by family structure and grandparent co-residence as at Wave 1.

- In families of 0-1 year olds (the B cohort), single parents without a co-resident grandparent were the most likely to have experienced some hardships, with 21% having experienced three or more hardships, 20% experiencing two hardships and 27% experiencing one hardship. In contrast, single parents with a co-resident grandparent were much more like couple parent families, although with slightly more experiencing one or more hardships. The number of financial hardships varied little for households of two parents according to whether or not grandparents were present.

- In the families of the 4-5 year old children (in the K cohort), single-parent households with no co-resident grandparent were similar to those of the 0-1 year olds in the B cohort with respect to the number of hardships reported. As for the younger children, the single parents with no co-resident grandparent were the most likely to have experienced hardships. The single parents with grandparents, however, were less like the two-parent families in the families of 4-5 year olds, having a higher likelihood of experiencing hardships than two-parent families.

For both cohorts, two parents with co-resident grandparents were less likely to experience hardships than single parents with co-resident grandparents. These findings are consistent with analyses for the US, in which Dunifon et al. (2014) explained that these differences have to do with differences in home ownership within these two groups, with housing of two parents more often owned by those parents, and single parents more often living in homes owned by the grandparents. This is also consistent with what is suggested by the housing tenure information presented above.

Figure 2.3: Number of financial hardships experienced by grandparental co-residence, household type and cohort, Wave 1

Source: B and K cohorts, Wave 1

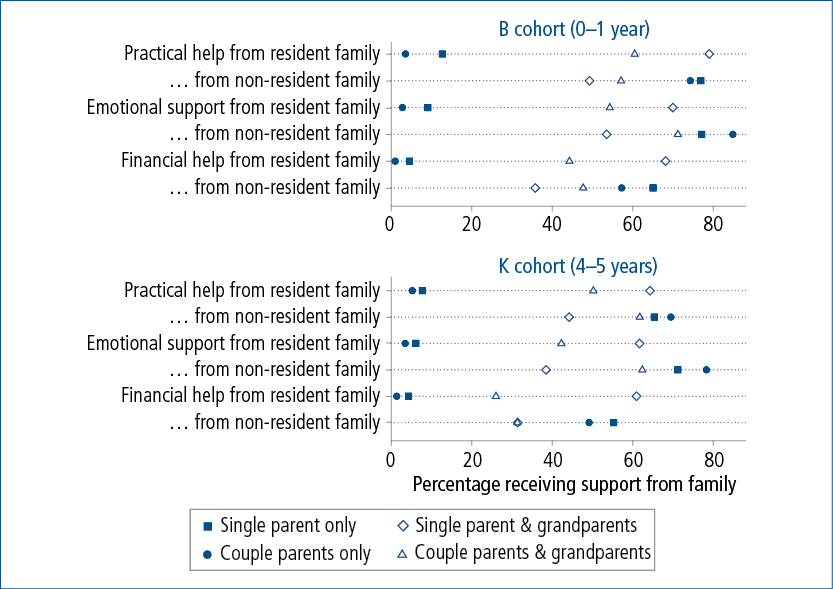

The provision of help and support by co-resident grandparents to parents is also apparent in Figure 2.4, which shows (using Wave 1) the percentage of parents reporting that they received practical help, emotional support or financial help from resident family or from non-resident family. Parents with co-resident grandparents, and especially single parents, said very often that they received any of these forms of help or support from resident family, which we would assume includes grandparents in many cases. Note, though, that not all parents with co-resident grandparents report that they receive these forms of help or support from resident family. The figure also shows that those parents who do not live with a grandparent were more likely to receive help or support from non-resident family, compared to those with a co-resident grandparent, although the differences were not always very marked.

What we do not know is to what extent LSAC parents (or indeed children) provide some degree of help or support to the co-resident grandparents. It seems likely that this would occur, especially when co-resident grandparents are older or need help managing a medical condition.

We can look further at the characteristics of the grandparents themselves, with information available on grandparents' age, main language spoken and medical conditions. This offers some insights on the characteristics of these grandparent co-resident households. (Note that this information cannot be used to identify which grandparents are likely to be co-resident, given we do not have a reference group of non-co-resident grandparents.)

Looking at grandparents co-resident with 0-1 year olds (B cohort, Wave 1):

- The median age of co-resident grandmothers was 53 and of co-resident grandfathers was 55 (5% of grandmothers and 9% of grandfathers were aged over 70 years).

- Thirty-six per cent of co-resident grandmothers and co-resident grandfathers had a long-term health condition (i.e., a medical condition or disability that had lasted or was likely to last for 6 months or more).

- Twenty-one per cent of co-resident grandmothers and 19% of co-resident grandfathers mainly spoke a language other than English at home.

Among grandparents co-resident with 4-5 year olds (K cohort, Wave 1):

- The median age of co-resident grandmothers was 61 and of co-resident grandfathers was 64 (23% of grandmothers and 34% of grandfathers were aged over 70 years).

- Forty-seven per cent of co-resident grandmothers and 44% of co-resident grandfathers had a long-term health condition.

- Thirty per cent of co-resident grandmothers and 35% of co-resident grandfathers mainly spoke a language other than English at home.

Figure 2.4: Receipt of help and support from resident and non-resident family, by cohort, grandparent co-residence and household type, Wave 1

Source: B and K cohorts, Wave 1

These age differences (across cohorts, and of grandmothers and grandfathers) would be expected (see section 2.2). The higher incidence of health conditions for grandparents of 4-5 year olds might also reflect the age differences between these grandparents and those of the 0-1 year olds. However, within cohorts, health differences did not emerge when comparing grandmothers to grandfathers. When these characteristics were explored across waves, there was considerable variation, such that the only (unsurprising) trend was for grandparents to be older at later waves. Some differences were apparent according to whether grandparents were living with the LSAC children in a single-parent or two-parent household, as shown for data pooled across waves in Figure 2.5. Grandparents were older and more likely to be non-English speakers in couple-parent households than in single-parent households. Differences were not apparent for grandparents' likelihood of having a long-term medical condition.

The findings from this section are summarised and discussed further in the final section of this chapter, after the analyses of grandparents as child care providers, and grandparents' contact with children.

2.4 Grandparents as child care providers

This section focuses on grandparents as child care providers. In Australia, grandparents are a key source of child care, especially when children are very young and when mothers are employed (Baxter, 2013; Jenkins, 2010). Australian research has highlighted the significance of grandparent care, including research using LSAC (Baxter, 2014; Baxter et al., 2007; Gray et al., 2005; Hand & Baxter, 2013) and other data sources (Baxter, 2013; Horsfall & Dempsey, 2011, 2013; Weston & Qu, 2009). Likewise, international literature has shown that families greatly value grandparent-provided care and often use it as a supplement or alternative to formal care arrangements (Brandon, 2000; Goodfellow & Laverty, 2003; Wheelock & Jones, 2002).

Figure 2.5: Grandparent demographics averaged across five waves, by cohort and household type

Note: Based on pooled data on co-resident grandparents across waves, and so show average characteristics across waves. For grandmothers, n = 1,756 from 923 families with co-resident grandmothers at one or more waves. For grandfathers, n = 1,124 from 620 families with co-resident grandfathers at one or more waves. For each, there were fewer observations for a medical condition, which was not available in Wave 4.

Source: B and K cohorts, Waves 1 to 5

This section extends existing research on grandparent-provided child care in Australia, to provide more detail about the nature of that care, and on the extent to which grandparent care supplements other forms of care. Where possible, we analyse whether care was provided by maternal or paternal grandparents, but we do not have information on whether that care was provided by grandmothers or grandfathers, as has been explored by Horsfall and Dempsey (2013) and Hank and Buber (2009), for example.

First, this section begins with a broad overview of grandparent-provided child care across the ages of children in the two cohorts of LSAC. Then, more detail is provided in two separate subsections, one on care for under-school-aged children and the other on school-aged children.

For children under school age, information about child care was collected in LSAC by asking parents about their regular use of child care over the previous month, excluding casual or occasional babysitting.8 Details of children's participation in formal child care (such as long day care or family day care) or informal care (such as grandparent or other relative care) were collected and, at the appropriate ages, this was captured separately to participation in preschool. When children became school-aged, parents were asked about their current use of care for children before school, after school or at other times. There were some changes to questions used to capture this information across the waves.9 Care for school holidays was also collected for school-aged children but this is not covered in this chapter - see Baxter (2014) for analyses of these data.

Overview of grandparent-provided child care

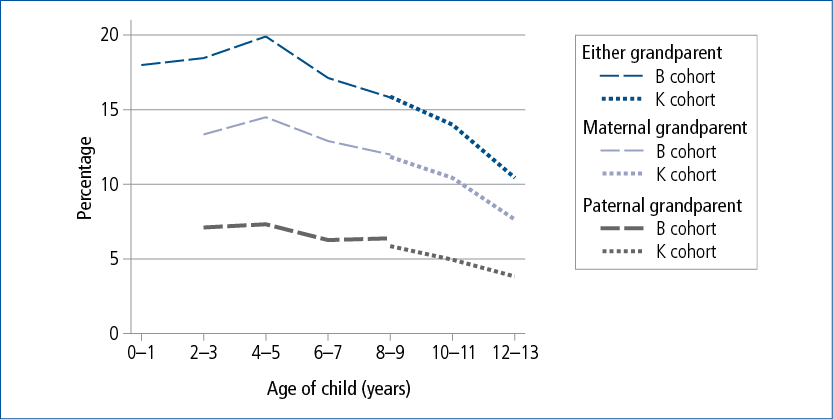

To first provide an overview of grandparent-provided child care, Figure 2.6 shows the percentage of children (by age and cohort) who were regularly cared for by grandparents. From Wave 2, this was separately identified as care provided by a maternal grandparent or paternal grandparent, as shown. The percentage of children in some grandparent care was highest when children were under school age, with a decline in the proportion being cared for by grandparents as children progressed through the primary school years.

Figure 2.6 shows that at any age children were more often cared for by maternal grandparents than by paternal grandparents. For example, 18% of children aged 2-3 years were cared for by either grandparent and this included 13% cared for by maternal grandparents (72% of 2-3 year olds cared for by a grandparent) and 7% cared for by paternal grandparents (39% of 2-3 year olds cared for by a grandparent). As is evident in these data, some children were cared for by maternal grandparents as well as paternal grandparents (11% of those sometimes cared for by grandparents at this age).

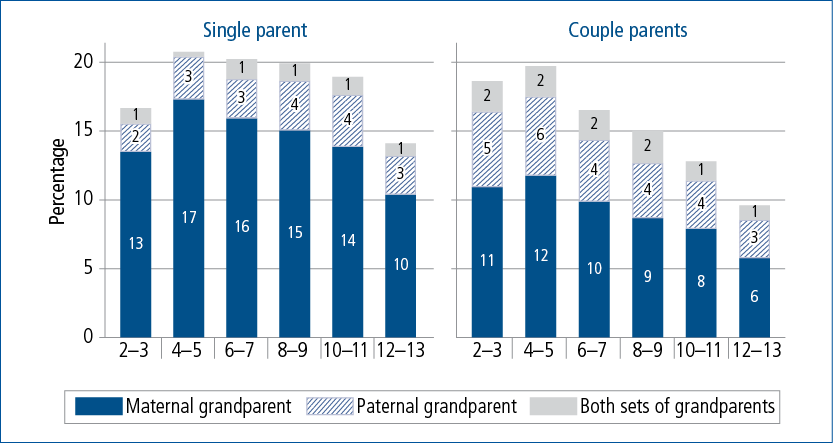

Among children cared for by a grandparent, those in single-parent households were less often cared for by paternal grandparents and more often cared for by maternal grandparents compared to children in two-parent households. Figure 2.7 shows this, for children aged 2-3 years and older.

Figure 2.6: Percentage of children with some grandparent care (maternal or paternal) by child age and cohort

Note: Grandparent care was not collected separately in respect to maternal or paternal grandparents in Wave 1.

Source: B cohort, Waves 1 to 5; K cohort, Waves 3 to 5

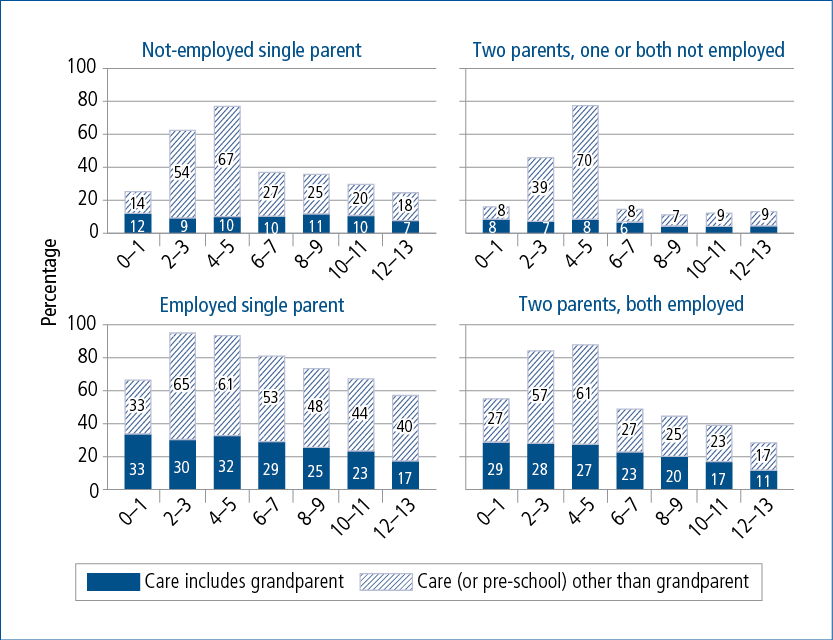

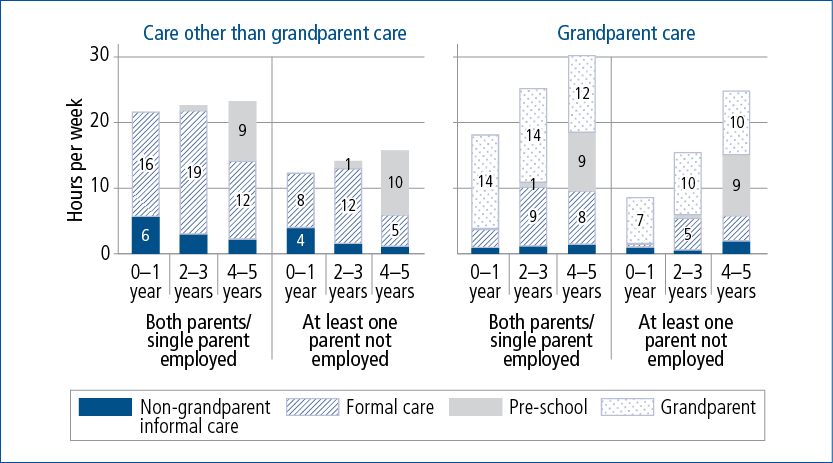

In addition to child age and parent's relationship status, children's care arrangements are expected to be strongly associated with parents' employment status (Baxter, 2013).10 This is apparent in Figure 2.8, which also contextualises the grandparent child care with other forms of care or preschool. For children with a not-employed parent, there were lower percentages in care or preschool overall, although at ages 2-3 years and 4-5 years, care was often used, which no doubt reflects that formal care or preschool is especially valued as children approach school age, given the opportunities these arrangements provide for social and educational development (Hand, Baxter, Sweid, Bluett-Boyd, & Price-Robertson, 2014). Grandparent care, however, did not have the same pattern by child age for these families, with the percentage in grandparent care varying only slightly as children grew.

Figure 2.7: Grandparent care by maternal and paternal grandparents, by child age and household type

Note: Grandparent care was not separately identified as maternal or paternal at Wave 1.

Source: B cohort, Waves 2 to 5; K cohort, Waves 3 to 5

Figure 2.8: Grandparent and other care, by child age and parents' employment status

Notes: Care other than grandparent includes informal or formal care. Informal care includes friends or neighbours, other relatives, a parent living elsewhere or nannies. Formal care includes long day care, occasional care, family day care, before or after school care or preschool or kindergarten.

Source: B cohort, Waves 1 to 5; K cohort, Waves 3 to 5

Among children with employed parents, the percentages in any care were significantly higher than for children with a not-employed parent across all ages, except for at 4-5 years. Across all ages, this was reflected in a higher percentage in grandparent care. Also across all ages, children with employed single parents were more likely to be in some grandparent care, compared to children with two employed parents. The differences were quite small at some ages, though. There were far greater differences between employed single parents and dual-employed couple parents in relation to children's participation in care other than grandparent care. This was most likely in the single-parent households.

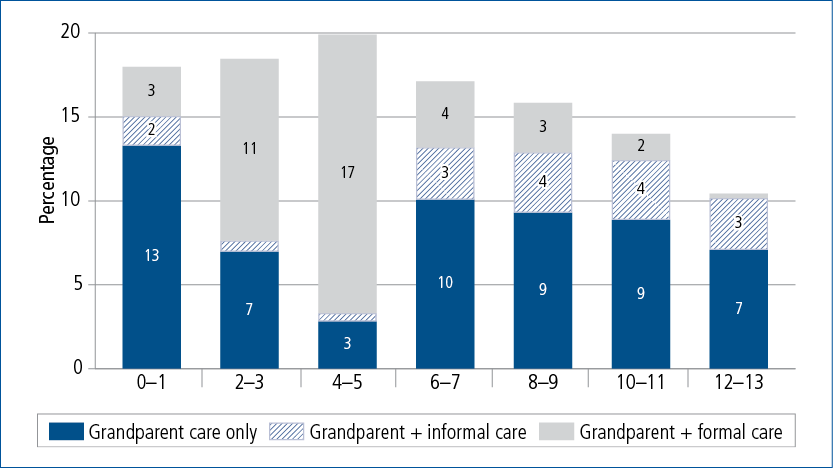

Figure 2.9 looks in more detail at the care arrangements of children who have some grandparent child care. Overall, children cared for by a grandparent were often also in other care arrangements; however, this varied considerably by child age. At 0-1 year, 18% of children were in grandparent child care. Of those, 13% were only in grandparent care. By 2-3 years, out of 18% in grandparent care, only 7% were only in grandparent care, and at 4-5 years, 3% were only in grandparent care out of a total of 20% in some grandparent care. Once children were school age, it was more likely that children were only in grandparent care rather than a combination of grandparent and other care.

Figure 2.9: Children in grandparent care, showing grandparent care combinations with other care types, by child age

Notes: Informal care includes friends or neighbours, other relatives, a parent living elsewhere or nannies. Formal care includes long day care, occasional care, family day care, before or after school care or preschool or kindergarten.

Source: B cohort, Waves 1 to 5; K cohort, Waves 3 to 5

Parents' employment status and children's age are key characteristics in describing which children are cared for by grandparents, as seen above and as evident in other research (Baxter, 2014; Hand & Baxter, 2013; Silverstein & Marenco, 2001; Vandell, McCartney, Owen, Booth, & Clarke-Stewart, 2003). While it is of interest to examine which other characteristics of families predict greater use of grandparent care, we leave this to further research, as this would require more comprehensive analyses than can be covered here. It is worth noting, however, the connection between the provision of grandparent care and the focus of the previous subsection on grandparent co-residence. Not surprisingly, children were more likely to be cared for by a grandparent when they shared a home with one. Among children with a co-resident grandparent, grandparents provided care to 55% of under-school-aged children and 50% of school-aged children with employed parents; 18% of under-school-aged children and 25% of school-aged children with a not-employed parent. In comparison, among children without a co-resident grandparent, grandparents provided care to 27% of under-school-aged children and 18% of school-aged children with employed parents; 8% of under-school-aged children and 5% of school-aged children with a not-employed parent.

The longitudinal nature of LSAC allows us to explore to what extent grandparent child care is experienced across the waves of LSAC, to examine the stability of this care arrangement. (This is just done for the B cohort, over ages 0-1 year through to 8-9 years, since we have not used the first two waves of the K cohort to analyse grandparent care.) In this cohort, 44% of children had been cared for by a grandparent at one or more of the five waves. Overall, 19% were in grandparent care at one wave only. Most commonly, this one wave was when the children were aged 0-1 year, although significant proportions were only in grandparent care at each of the other four waves. Another 11% were in grandparent care at two waves, with the grandparent care more often occurring during the under-school ages. The remainder were 7% having been in grandparent care for three waves, 4% for four waves and 2% for five waves. These findings suggest that grandparent care is not a persistent or consistent form of care for many children across their early years. This is likely to reflect that parents' needs for any child care change as parents (usually mothers) move into and out of employment, as children spend more time in formal care or preschool, and as the availability of grandparents changes.

The two following subsections now provide some more detail about care provided to under-school-aged children and school-aged children.

Under-school-aged children

This subsection includes information on grandparent care of under-school-aged children. These analyses use data from the B cohort (Waves 1 to 3) and the K cohort (Wave 1), excluding 4-5 year old children who were already in school.11

Looking first at the average amounts of time children are in grandparent care, the LSAC data show that, among children who were in any sort of child care:12

- At 0-1 year, the average duration of care per week was 17.3 hours. This included an average of 6.4 hours cared for by grandparents, 3.0 hours in other informal care and 8.0 hours in formal child care.

- At 2-3 years, the average duration of care (including preschool) per week was 20.5 hours. This included an average of 3.6 hours cared for by grandparents, 2.0 hours in other informal care, 14.0 hours in formal child care and just less than 1.0 hour in preschool.

- At 4-5 years, the average duration of care (including preschool) per week was 21.6 hours. This included an average of 2.3 hours cared for by grandparents, 1.6 hours in other informal care, 8.3 hours in formal child care and 9.3 hours in preschool.

- Across the under-school-aged period, formal care is the most common care arrangement, followed by grandparent care, followed by other informal care.

Figure 2.10 presents information on the average weekly hours children were in different forms of care, by parental employment status and child age, and separating those who were in some grandparent care from those who were not.

- For children with employed parents who did not have grandparent care, the average amount of care changed little as children grew through the under-school ages, remaining at around 21 hours per week. The type changed, such that children spent more time in preschool at 4-5 years than at earlier ages.

- For children with care other than grandparent care who had a not-employed parent, the average hours in care increased, reflecting more time in formal child care at 2-3 years, then more time in preschool (offset by less time in child care) at 4-5 years.

- For children with employed parents who did have grandparent care, the amounts of time in care changed considerably as children grew, although the time spent cared for by grandparents did not change a great deal. These children spent, on average, 14 hours per week being cared for by grandparents at 0-1 year and 2-3 years, and 11 hours per week at 4-5 years. Their time in other forms of care changed over these ages, with more time in formal child care at 2-3 years and more time in preschool at 4-5 years.

- Children who had some grandparent care and a not-employed parent spent an average of 7 hours in grandparent care at 0-1 year, then an average of 10 hours per week at 2-3 years and 4-5 years. Like the other children, their time in formal child care was higher at 2-3 years and in preschool at 4-5 years.

Figure 2.10: Mean weekly hours in care types for children in some care, by whether care includes grandparent care, age and mothers' employment status

Source: Waves 1 to 3 of the B cohort and Wave 1 of the K cohort

Table 2.3 provides some more information about the grandparent-provided child care.13

- Figure 2.9 showed how grandparent care was combined with other forms of child care, by child age. Here this is evident also, with grandparent care reported to be the main form of care for 86% of 0-1 year olds in grandparent care, 63% of 2-3 year olds and 31% of 4-5 year olds.

- Among children in grandparent care, this care was more often provided in the child's home when children were aged 0-1 year (45% were cared for in their own home), compared to 34% at 2-3 years old and 32% at 4-5 years old. Among children who were cared for somewhere else, this was most likely to be in the home of their grandparents.

- Information about the hours spent in grandparent care allow some elaboration beyond the averages shown above. There was considerable variation in the number of hours children were cared for by grandparents. For example, at 0-1 year, 26% spent less than 5 hours per week in grandparent care, 33% spent 5-9 hours per week in grandparent care, 21% spent 10-19 hours per week in grandparent care and 20% spent 20 hours or more in grandparent care. The distribution of hours did not vary greatly from this at 2-3 years or 4-5 years.

- Looking at how many days per week children were in grandparent care, it was most common for children to have been cared for just 1 day a week (about half the children in grandparent care), with about one in four cared for 2 days per week, and the rest distributed over other numbers of days.

- There were often two (or more) adults present when the child was being cared for by grandparents. Presumably this often indicated the presence of both a grandmother and grandfather. This was the case for 40% of 0-1 year olds, 46% of 2-3 year olds and 49% of 4-5 year olds in grandparent care. For the balance, just one adult was usually present.

- The number of months in total that children experienced grandparent care of course varies by age, but even looking at the older children here, there were very diverse experiences. At 4-5 years, 17% of children experienced grandparent care for most of their life (4 years or more) and another 14% had been in grandparent care for 3 years or more.

| Selected characteristics | 0-1 year (B cohort, Wave 1) (%) |

2-3 years (B cohort, Wave 2) (%) |

4-5 years (B cohort, Wave 3 K cohort, Wave 1) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grandparent care is main care | |||

| Yes | 86.1 | 63.2 | 30.8 |

| No | 13.9 | 36.8 | 69.2 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Care provided in child's home | |||

| Yes | 44.5 | 34.3 | 32.2 |

| No | 55.5 | 65.7 | 67.8 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Hours in grandparent care | |||

| Less than 5 hours | 26.4 | 19.5 | 25.0 |

| 5-9 hour | 33.3 | 35.2 | 36.4 |

| 10-19 hours | 20.7 | 23.8 | 22.4 |

| 20 hours or more | 19.6 | 21.5 | 16.3 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Days per week in grandparent care | |||

| 1 | 48.3 | 53.6 | 55.3 |

| 2 | 26.7 | 23.3 | 22.8 |

| 3 | 9.8 | 10.2 | 10.7 |

| 4 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 2.5 |

| 5 | 9.0 | 8.1 | 7.1 |

| 6 or 7 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 1.6 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Number of adults present | |||

| One | 60.3 | 54.3 | 51.5 |

| Two or more | 39.7 | 45.8 | 48.5 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| How long child has been in this care | |||

| 0-5 months | 65.4 | 19.9 | 22.4 |

| 6-11 months | 32.3 | 12.4 | 13.1 |

| 12-23 months | 2.3 | 31.2 | 17.8 |

| 24-35 months | n.a. | 34.1 | 15.5 |

| 36-47 months | n.a. | 2.4 | 14.2 |

| 48 months or more | n.a. | n.a. | 17.1 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| No. of observations | 926 | 874 | 1,729 |

Note: Children aged 4-5 years already attending school are excluded. Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Source: Waves 1 to 3 of the B cohort and Wave 1 of the K cohort

In addition, across all these ages under school age (but not shown in Table 2.3):

- Ninety-eight per cent of parents of under-school-aged children reported that when children were in grandparent care, there were usually one to five children present. We can expand on this from information provided by grandparents who responded, in Waves 1 or 2, to the home-based carer component of LSAC.14 Almost all grandparents reported that they were caring only for the study child when the child was aged 0-1 year, while 61% said they were caring only for the study child at 2-3 years, and another 37% said they were caring for up to five children.

- Few parents (5-6%) paid the grandparents for the child care they provided. Not surprisingly, then, according to the grandparent respondents, 99% reported that they were not Child Care Benefit registered carers.

School-aged children

This section presents further information on the care provided to school-aged children by their grandparents. The analyses span the ages 6-7 years (Wave 4 of the B cohort), 8-9 years (Wave 5 of the B cohort and Wave 3 of the K cohort), 10-11 and 12-13 years (Waves 4 and 5 of the K cohort). Prior to Wave 3, the questions about child care for school-aged children differed, and so those data (Wave 2 of the K cohort) were not used.

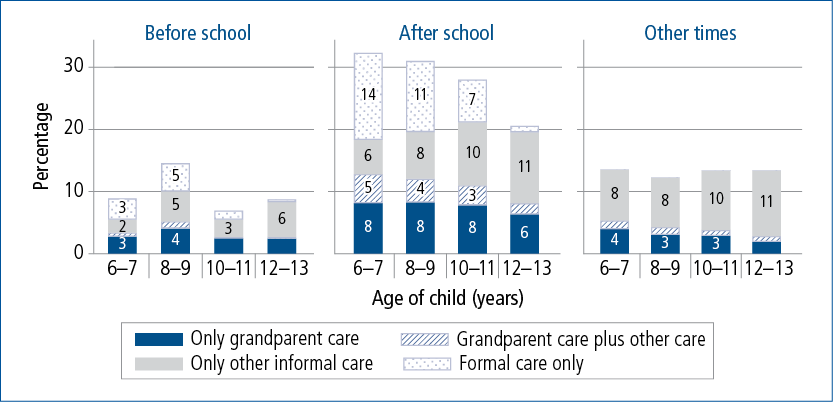

The additional information provided here relates to the time of day that grandparent and other care is provided to school-aged children. Figure 2.11 shows child care according to whether it was provided before school, after school, or at other times (weekends or evenings). Children in some child care are classified according to whether they only had grandparent care, they had grandparent care plus some other (formal or informal) child care, they only had informal child care other than grandparent care, or they had formal child care (including those who also had non-grandparent informal care).

The peak time for child care for school-aged children was after school:

- Just less than one third of 6-7 year olds were in some after-school care, although this declined considerably as children grew, with 20% of the 12-13 year olds in some after-school care.

- At age 6-7 years 13% of children were cared for by grandparents after school (8% by only grandparents and 5% had grandparent care and some other care). This declined as children grew, with 8% cared for by grandparents after school at age 12-13 years.

- Changes in formal and non-grandparent informal care after school were much more apparent as children grew, with a decline in the proportion in formal child care and an increase in the proportion in informal (non-grandparent) arrangements.

Figure 2.11: Grandparent and other care of school-aged children, by time of day and child age

Note: Children may be in grandparent care at more than one of the specified times.

Source: Waves 4 and 5 of the B cohort (age 6-7 and 8-9 years) and Waves 3 to 5 of the K cohort (age 8-9, 10-11 and 12-13 years)

Before school hours, the arrangements were more diverse and the patterns by child age more varied. Fewer than 5% of children were cared for by grandparents before school hours.

For care at other times, children were most often in informal arrangements other than grandparent care, with fewer than 5% cared for by grandparents at these times, declining slightly by child age.

The key findings from the above sections, in conjunction with other findings, are discussed after an examination of children's contact with grandparents, below.

2.5 Children's contact with grandparents

The final aim of this chapter is to explore to what extent children have face-to-face contact with their grandparents. Grandparent contact may take different forms, and our focus is on the most direct form of contact in which grandparents share some time together with the children. At one extreme, face-to-face contact will be expected especially when grandparents are co-resident with or regularly care for grandchildren. Some grandparents, however, will not be able to have such direct forms of contact, especially those who live some distance from the family, and for these, phone calls or other means of communication may allow different types of contact that will not be captured with the data available in LSAC. There will be some families, of course, who have no contact with children's grandparents, including those children with no living grandparents and those in which there are strained or distant relationships between children's parents and grandparents. In particular, the latter may be true in the case of some single-parent households, as contact with one set of grandparents may be disrupted by the parents' separation.15

This section explores the frequency of children's face-to-face contact with grandparents as children grow and across different family forms. Information about children's contact with grandparents primarily comes from questions on this, asked of the child's primary carer in the self-completion component of LSAC. These questions have changed across the waves of LSAC and, from Wave 2, the frequency of contact with maternal grandparents can be explored separately from contact with paternal grandparents.16 Given the changes in questions, a challenge has been in correctly taking account of children's contact with paternal grandparents in the case of single-parent families.17 The data do allow broad estimates of grandparent contact to be derived, though, so we have used these data to compare across different families. The information on children's contact with grandparents cannot be separated into information about contact with grandmothers versus grandfathers.

In all waves and for both cohorts, over 95% of children had at least some face-to-face contact with a grandparent, including those who "rarely" had contact with a grandparent, through to those who saw them every day. (The frequency of contact is explored below.) Contact with maternal grandparents was more common than contact with paternal grandparents:

- The percentage of children who had some contact with a maternal grandparent ranged from 94% of children age 2-3 to 88% of children age 12-13.

- The percentage of children who had some contact with a paternal grandparent ranged from 88% of children age 2-3 to 82% of children age 12-13.

Some of the decline in children having contact with grandparents, as children grow, has been due to the death of those grandparents, as discussed in section 2.2. For example, 2% of 2-3 year old children (in the B cohort at Wave 2) were reported to have no maternal grandparents, but this was 7% of children at 12-13 years (in the K cohort at Wave 5). Children with no grandparents are still included in the calculations.

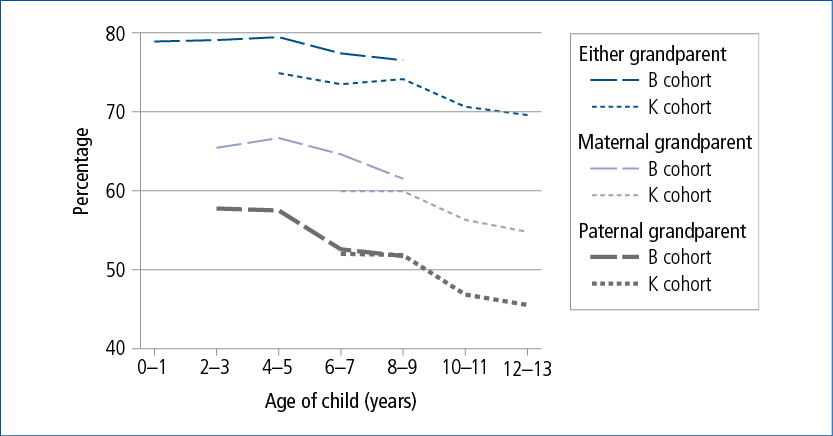

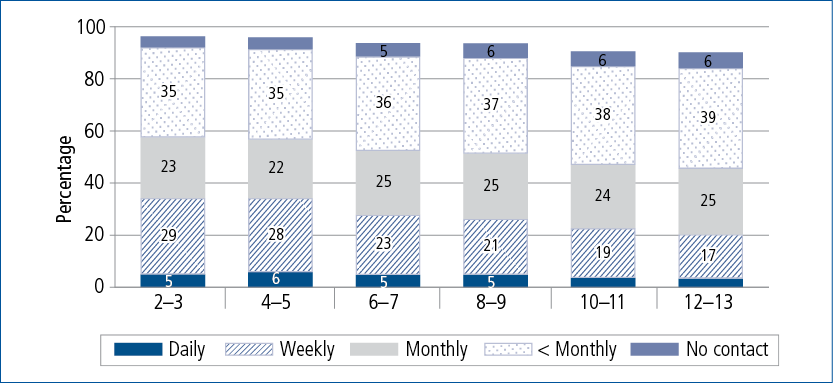

While most children had some contact with their grandparents, regular contact was less common. Figure 2.12 shows the percentage of children, by age and cohort, who had at least monthly contact with their grandparents (with estimates of regular contact for children with a parent living elsewhere, as described in footnote 18).

The percentage of children having at least monthly contact with a (maternal or paternal) grandparent was highest when children were under school age and declined with the age of the child. Still, the majority of children keep in regular contact with grandparents. Around 80% of children had at least monthly contact with a grandparent at 4-5 years, compared to 70% of children aged 12-13 years. The patterns by the child's age are similar to those reported previously for grandparent-provided child care (Figure 2.6). As already discussed, the trends in contact by the child's age may be more a reflection of the ageing of the grandparents, rather than of the children themselves. Similarly, differences in contact between maternal and paternal grandparents will partly be explained by children being less likely to have paternal than maternal grandparents, given that maternal grandparents are likely to be younger.

Across all ages, it was more common for children to have regular (at least monthly) contact with their maternal grandparents than their paternal grandparents. By age 12-13, 55% of children had regular contact with their maternal grandparents, compared to 46% for paternal grandparents.

Figure 2.12: Percentage of children who have at least monthly contact with (maternal or paternal) grandparents, by age and cohort

Note: Refer to footnotes 17 and 18 for information about derivation of these data.

Source: Waves 1 to 5 of the B and K cohorts.

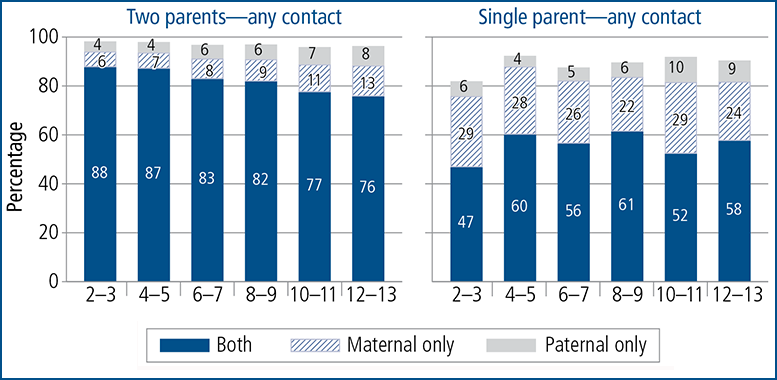

When we explored differences in maternal and paternal grandparent involvement in previous sections, the higher rates of maternal grandparent involvement were particularly apparent in single-parent households, with differences less marked within two-parent households. Consistent with this, Figure 2.13 shows that for grandparent contact, compared to children in two-parent households, those in single-parent households were much less likely to have contact with both sets of grandparents, and more likely to be only in contact with their maternal grandparents. (As noted previously, the vast majority of single parents are single mothers.) This figure shows the percentage of children who have any contact with their grandparents, depending on whether they are living in a two-parent or a single-parent household. The height of each bar gives the percentage who have some contact with either grandparent, such that the balance is those with no grandparents and with no contact with grandparents. In analyses below we explore this more.

Figure 2.13: Percentage of children who have any contact with (maternal or paternal) grandparents, by child age

Notes: Refer to footnotes 17 and 18 for information about derivation of these data. “Any contact” includes monthly contact or less regular contact. The balance includes children with no contact with grandparents and those who do not have grandparents.

Source: Waves 2 to 5 of the B and K cohorts

Among children in two-parent households, the majority had some contact with both sets of grandparents through the ages of 2-3 to 12-13 years. Still, the percentage of children who had contact with both sets of grandparents declined slightly over time; and of those children in two-parent households who only had contact with one set of grandparents, it was more common for that contact to be with their maternal, rather than their paternal grandparents.

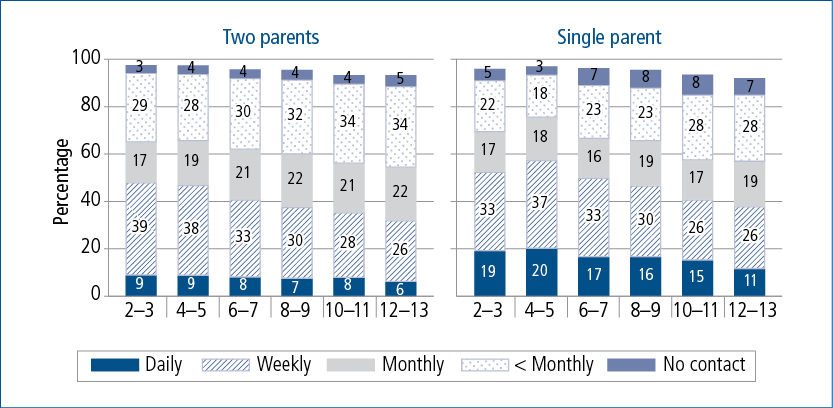

Focusing just on children's contact with maternal grandparents, Figure 2.14 shows a larger proportion of children in single-parent households seeing their maternal grandparents daily or weekly. This is mainly explained by children in single-parent households being more likely than those in two-parent households to co-reside with their grandparents (as explored in Section 2.3).18 Other key findings are:

- Regardless of whether the child lived with one or two parents, the percentage of children who had daily or weekly contact with maternal grandparents declined with age.

- Very few children at any age have grandparents with whom they never had face-to-face contact.

- The height of the columns in Figure 2.14, which represents the percentage of children with maternal grandparents, declines with the age of the child.

Figure 2.14: Frequency of contact with maternal grandparents, by child age and parents' relationship status

Notes: Column height represents the percentage of children who had maternal grandparents. Where the amount of contact is unknown, contact is assumed to be at least monthly.

Source: Waves 2 to 5 of the B and K cohorts

To explore children's contact with paternal grandparents, we focus in Figure 2.15 only on two-parent households, because of the difficulty in deriving this information for single-parent households. As Figure 2.13 showed, children have somewhat less contact with paternal grandparents compared to maternal grandparents, and this was also apparent in children being less likely to have daily or weekly face-to-face contact with paternal grandparents.19

- At 2-3 years, 48% of children in two-parent households had either daily or weekly contact with a maternal grandparent but only 34% had daily or weekly contact with a paternal grandparent.

- By the age of 12-13, these percentages dropped to 32% for maternal grandparents and 20% for parental grandparents.

Single-parent households were not included in Figure 2.15, as the frequency of children's contact with their other parent's parents was not collected from the primary carer. (They, in fact, may not know how often the child sees these grandparents.)

Figure 2.15: Frequency of contact with paternal grandparents, by child age, two-parent households

Notes: Column height represents the percentage of children who had paternal grandparents. Where the amount of contact is unknown, contact is assumed to be at least monthly.

Source: Waves 2 to 5 of the B and K cohorts

While contact with grandparents becomes less frequent as children grow, it is not the case that children usually go from having regular contact with their grandparents to having hardly any contact. In fact, if we explore how grandparent contact changes as children grow, we find the amount of contact with grandparents increases for some children over time. For example, among children in the B cohort who were living in two-parent households at age 2-3 and 8-9 years:

- Of those who had daily contact with a (maternal or paternal) grandparent at 2-3 years, 36% still had daily contact at 8-9 years; while 42% saw them weekly and 10% saw them monthly.

- Of those who had weekly contact at 2-3 years, 59% still had weekly contact at 8-9 years, while 26% saw them monthly at 8-9 years, and 7% had increased their contact to daily.

- Among children with monthly contact with a grandparent at 2-3 years, 50% were still seeing grandparents monthly at 8-9 years. While 27% of these children at 8-9 years saw grandparents less frequently, 21% had increased their contact to weekly.

- Of those children who had less than monthly contact with a grandparent when they were 2-3 years old, this was still the case at 8-9 years for 62% of children, but 11% had moved to monthly contact and 20% to at least weekly contact with a grandparent.

The above analyses have shown that it is quite common for children to have at least some contact with their grandparents, and regular contact is more common for maternal than paternal grandparents, particularly for children in single-parent households. Many factors can influence the amount of contact that grandparents have with their grandchildren, some key ones are likely to be geographical distance, grandparents' health status and their own employment status, and the nature of the grandparents' relationship with the child's parents. We do not have information on geographical distance, nor do we know about the health status of grandparents who are not resident in the LSAC household. We do not know about grandparents' employment, even if they are co-resident. Information is also not collected that allows some classification of the quality of the parent-grandparent relationship at the time of the survey.

It is likely that parents' own childhood experiences might contribute to later relationships with parents. In Table 2.4, we consider whether grandparent contact varies according to parents' feelings about the happiness of their childhood. For simplicity, this has just been done for mothers' reports of happiness, against children's contact with maternal grandparents (having at least monthly contact, versus no or less regular contact). The table shows that in both cohorts, children were more likely to have at least monthly contact with their maternal grandparents if their mother reported having a happy childhood, with the highest percentage having at least monthly contact when mothers said they had a "very happy" childhood. Still, even among children whose mothers reported having an unhappy or very unhappy childhood, just over half of children in the B cohort and 45% of children in the K cohort had at least monthly contact with their maternal grandparents.

| Mother's rating of happiness in childhood | Child's face-to-face contact with maternal grandparents | Mother's contact (see/talk/email) with child's maternal grandparents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At least monthly (%) | No or less regular contact (%) | Total (%) | At least weekly (%) | No or less regular contact (%) | Total (%) | |

| B cohort (age 2-3) | ||||||

| Very happy | 73.1 | 26.9 | 100.0 *** | 91.3 | 8.7 | 100.0 *** |

| Pretty happy | 65.9 | 34.1 | 100.0 | 83.0 | 17.0 | 100.0 |

| Unhappy/Very unhappy | 52.8 | 47.2 | 100.0 | 60.2 | 39.8 | 100.0 |

| All | 67.4 | 32.6 | 100.0 | 83.9 | 16.1 | 100.0 |

| K cohort (age 6-7) | ||||||

| Very happy | 67.5 | 32.5 | 100.0 *** | 88.9 | 11.1 | 100.0 *** |

| Pretty happy | 62.6 | 37.5 | 100.0 | 77.7 | 22.3 | 100.0 |

| Unhappy/Very unhappy | 45.2 | 54.8 | 100.0 | 56.1 | 43.9 | 100.0 |

| All | 62.6 | 37.4 | 100.0 | 79.2 | 20.8 | 100.0 |

Notes: Sample is restricted to children with maternal grandparents whose mothers responded to the question about childhood happiness. Significance (chi-square) tests used to compare proportions with, without monthly contact with grandparents. *** p < .001; ** p < .01; * p < .05; ns p > .05. Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Source: B and K cohorts, Wave 2

These data are likely to reflect stronger parent-grandparent relationships when parents' retrospective reports of their own childhood were happier. In fact, Table 2.4 also shows the frequency of contact between mothers and their parents, collected at the same time as the information on children's contact with these grandparents. For these data, "contact" is broader than face-to-face contact, and so we have shown the percentage having at least weekly contact.

- The majority of mothers have at least weekly contact with their mother (84% in the B cohort and 79% in the K cohort).

- Within each cohort, weekly contact is less likely when mothers reported having had an unhappy childhood, and is highest when mothers reported having had a very happy childhood.

Beyond these factors, there are likely to be demographic factors that could make a difference to the frequency or incidence of grandparents' contact with children. We explore here, whether grandparent contact varies according to parents' age, cultural background, education and employment. Table 2.5 shows that at Wave 1:

- When the child's primary carer was relatively young at the child's birth, families were significantly more likely to have daily contact with a grandparent, and this was especially marked in the B cohort. (This of course is affected by the fact - seen in section 2.3 - that grandparent co-residence is more likely in these families.) Children with older parents are significantly less likely to have regular face-to-face contact with their grandparents. This is likely to be related to the grandparents being older themselves when parents are older, such that grandparents' capacity for face-to-face contact with grandchildren may be adversely affected by their frailty or ill health, or perhaps more constrained financial circumstances.

- The main finding related to the primary carer's educational attainment is that of daily contact being more likely when the educational attainment is lowest. Again, this is likely to reflect the higher rates of grandparent co-residence in the households of the least educated primary carers. It is also possible that these families are less able to afford formal child care, and therefore regular child care is more likely to be provided by grandparents.

- Weekly or monthly contact with a grandparent was somewhat more likely when both parents (or the parent in single-parent households) were employed.

- Having daily grandparent contact was most likely if one of the parents mainly spoke a language other than English at home, which may reflect high rates of grandparent co-residence. However, these data also show relatively high rates of non-contact with grandparents in these families, which is likely to be due to geographical distance.

| Selected characteristics | Daily (%) |

Weekly or monthly (%) |

Less regular (%) |

No contact or don't have (%) |

Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B cohort | |||||

| Primary carer age at child's birth (years) | |||||

| 15 to 24 | 26.1 | 62.0 | 9.4 | 2.4 | 100.0 *** |

| 25 to 34 | 12.8 | 68.3 | 15.9 | 2.9 | 100.0 |

| 35 and over | 8.2 | 61.4 | 23.4 | 7.0 | 100.0 |

| Primary carer education | |||||

| Incomplete secondary only | 16.0 | 61.6 | 15.3 | 7.1 | 100.0 |

| Secondary, certificate or diploma | 15.5 | 65.1 | 15.7 | 3.8 | 100.0 |

| Bachelor degree or higher | 10.1 | 67.4 | 19.2 | 3.3 | 100.0 |

| Employment status | |||||

| Both parents (or single parent) employed | 13.0 | 69.9 | 15.4 | 1.7 | 100.0 *** |

| One (or both) parents not employed | 13.5 | 61.9 | 18.8 | 5.9 | 100.0 |

| Main language spoken at home | |||||

| Both (or single parent) mainly speaks English | 11.7 | 69.3 | 17.2 | 1.8 | 100.0 *** |

| One (or both) parents mainly speaks a language other than English at home | 22.1 | 44.7 | 17.0 | 16.2 | 100.0 |

| All families | 13.2 | 65.7 | 17.2 | 3.9 | 100.0 |

| K cohort | |||||

| Primary carer age at child's birth (years) | |||||

| 15 to 24 | 18.5 | 65.3 | 12.6 | 3.6 | 100.0 *** |

| 25 to 34 | 11.7 | 64.7 | 20.9 | 2.7 | 100.0 |

| 35 and over | 9.3 | 56.5 | 27.0 | 7.2 | 100.0 |

| Primary carer education | |||||

| Incomplete secondary only | 17.9 | 57.1 | 18.1 | 6.9 | 100.0 |

| Secondary, certificate or diploma | 13.0 | 62.5 | 21.0 | 3.5 | 100.0 |

| Bachelor degree or higher | 8.5 | 65.7 | 22.8 | 3.0 | 100.0 |

| Employment status | |||||

| Both parents (or single parent) employed | 13.0 | 66.7 | 18.5 | 1.8 | 100.0 *** |

| One (or both) parents not employed | 10.9 | 58.3 | 24.5 | 6.3 | 100.0 |

| Main language spoken at home | |||||

| Both (or single parent) mainly speaks English | 10.6 | 66.1 | 21.1 | 2.2 | 100.0 *** |

| One (or both) parents mainly speaks a language other than English at home | 19.6 | 45.0 | 22.4 | 13.0 | 100.0 |

| All families | 12.0 | 62.9 | 21.3 | 3.9 | 100.0 |

Notes: Significance (chi-square) tests used to compare, for each variable, the proportions with different levels of contact with grandparents. *** p < .001; ** p < .01; * p < .05; ns p > .05. Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Source: B and K cohorts, Wave 1

2.6 Summary and discussion

This chapter looked at three broad aspects of possible grandparent involvement in children's lives. First, the co-residence of grandparents with children was explored through analyses of grandparents who live with the study children and their parent/s in multi-generational households. Second, grandparents as child care providers was explored. Third, children's contact with grandparents was explored. These different perspectives allow us to see some of the varied ways grandparents' and grandchildren's lives may intersect, providing opportunities for building relationships, help and support across generations.

Overall, the analyses of grandparents' co-residence confirmed that it is not common in Australia for children to have a co-resident grandparent. Percentages are highest among the 0-1 year old children, at 7% of these children, or more than an estimated sixteen thousand 0-1 year old children across Australia. The very young children in single-parent households quite often shared a home with a grandparent. These analyses also showed that having a co-resident grandparent was more likely for some other demographic groups; in particular, those with young parents and from culturally diverse backgrounds (as indicated by language spoken at home). These patterns may reflect, in some families, a means of addressing housing and financial security, while in others, they may reflect cultural aspects of family formation. These findings are consistent with other research on grandparent co-residence, and on multi-generational families in Australia and the United States (Dunifon et al., 2014; Mutchler & Baker, 2009; Pilkauskas & Martinson, 2014).

There were clearly advantages for many families in having co-resident grandparents. This is especially true in single-parent households, as was observed for the United States by Mutchler and Baker (2009). For example, comparing single parents with a co-resident grandparent to those without, housing tenure was more often described as living rent-free when there was a co-resident grandparent, financial hardships were less often experienced, and there was significantly greater access to help or support within the family. In couple-parent households, the presence of a grandparent did not seem to confer benefits to the family to the same degree, suggesting that there may be different reasons for this co-residence, perhaps to benefit the grandparent or for reasons unrelated to the economic circumstances of the parent(s). The analyses of the characteristics of the grandparents themselves highlighted some differences for single-parent versus couple-parent households, with younger grandparents in single-parent households than in couple households; and grandparents in couple households more likely to speak a language other than English than those in single-parent households.

Families without grandparents living with them are still often able to draw upon their help, with grandparent-provided child care being a common way that grandparents provide assistance to families. Grandparent care is often used as a supplement to other forms of care, with formal care still playing an important role in many families, even those who do use some grandparent care. Children are generally not cared for by grandparents for very many hours per week, with the average ranging from 6.4 hours when children were age 0-1, to 2.3 hours per week for 4-5 year olds. However, at least for young children, it tends to be flexible (being provided in the home of the child or the grandparents) and free: two factors that are no doubt valued by parents.

Even when non-resident grandparents do not provide regular child care, a significant proportion still see their grandchildren frequently. That is, for many grandparents, their relationship with their grandchildren involves attention and attachment, but little day-to-day interaction, as described by Mutchler and Baker (2009). Our analysis has shown that while most children have at least monthly contact with a grandparent, regular contact with maternal grandparents is more common than with paternal grandparents, and, as one would expect, contact with paternal grandparents is much less common in single-parent households.