7. Adolescent help-seeking

7. Adolescent help-seeking

Adolescence is a period of complex developmental transition, characterised by heightened vulnerability to emotional and behavioural problems (Steinberg, 2005). Globally, mental health disorders are experienced by one in four young people aged 13-24 years (Belfer, 2008). Despite the high prevalence of mental health problems during adolescence, many young people do not seek help for their problems. Lawrence and colleagues (2015), for example, found that one third of Australian adolescents with a mental disorder had not accessed formal help (e.g. from health and school services). The reluctance of adolescents to seek professional help for their problems presents a significant barrier to the delivery of appropriate and timely care and can place them at greater risk of developing severe or extended mental health problems (Rickwood, Deane, & Wilson, 2007).

Understanding who adolescents go to for help for their personal and emotional problems is important to inform appropriate pathways of care. This chapter describes the past help-seeking behaviours and future help-seeking intentions of adolescents, focusing on who adolescents go to for help. The help-seeking behaviours and intentions of adolescents who are experiencing symptoms of mental health difficulties are compared with those of adolescents with no symptoms of mental health difficulties.

7.1 Who do adolescents go to for help?

Adolescents may be more willing to seek help for their personal and emotional problems from informal sources, including family members and friends (Lawrence et al., 2015; Rickwood, Deane, Wilson, & Ciarrochi, 2005). This can be viewed as less confronting than talking to an unknown professional (Raviv, Sills, & Wilansky, 2000). Internet and telephone mental health services are also being increasingly utilised by young people, and are advantageous because they are easily accessible, informative and commonly anonymous (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2014). They also reduce many of the barriers to adolescent help seeking including geographical boundaries, service fees, stigma and embarrassment (Kauer, Mangan, & Sanci, 2014; Nicholas, 2004).

Box 7.1: Help-seeking measures in LSAC

Help seeking was measured when study children in the LSAC K cohort were aged 10-11 (Wave 4), 12-13 (Wave 5) and 14-15 (Wave 6) years.

At Waves 4 and 5, children were asked, 'If you had a problem, who would you talk to about it?' and indicated whether or not they would talk to a range of sources (e.g. mum, dad, teacher).

At Wave 6, adolescents were asked whether they had sought help for a personal or emotional problem in the last 12 months from a wider range of sources (e.g. parent, friend, teacher, family doctor, mental health professional and phone and internet services). They also reported on how likely it is that they would seek help from the same sources for a personal or emotional problem in the next four weeks.

The LSAC data show that at each adolescent age group, more adolescents reported help seeking from friends and parents than from teachers. At age 10-11, for example, 90% of young people said they would talk to their mother about a problem, while only 42% would talk to a teacher in the future (Table 7.1). At age 14-15, 69% reported seeking help for a personal or emotional problem from either parent, while 25% sought help from a teacher in the last 12 months (Table 7.2). Help seeking from mental health professionals or doctors, measured only at age 14-15, was reported by only 9% and 6% of adolescents respectively.

Figure 7.1: 14-15 year olds who sought help from a mental health professional

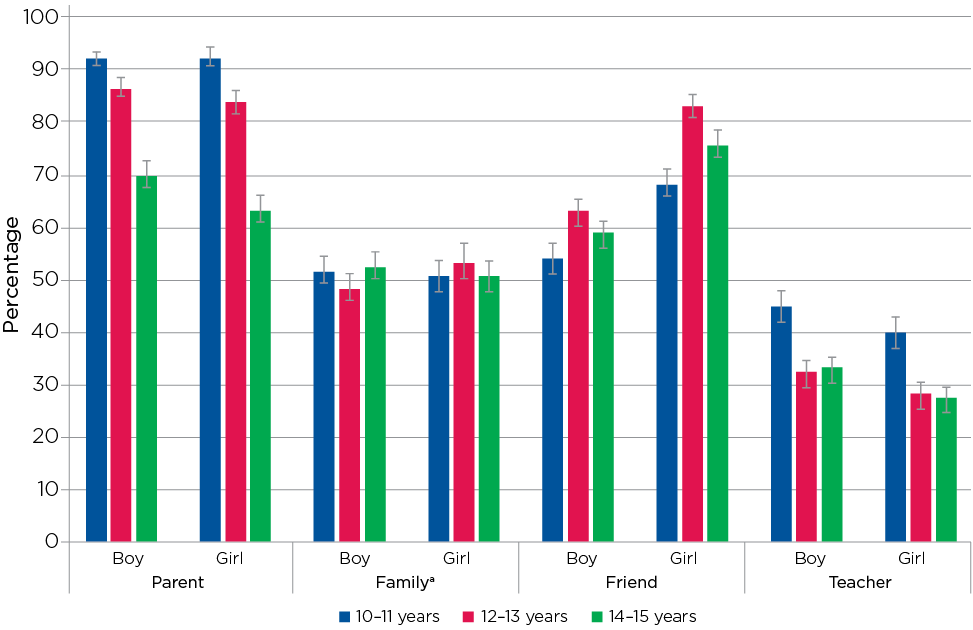

As adolescents grow older and experience increasing independence and evolving relationships, it is possible that the source of help they seek for a personal or emotional problem will change (Rickwood et al., 2007). Previous research has also consistently reported gender differences in help seeking, with females being more likely than males to seek help from friends (Rickwood et al., 2005; Sen, 2004). The LSAC data show that the percentage of study children who said that they would seek help from parents, friends and teachers if they had a problem changed as they got older; but willingness to seek help from a friend was more common for females than males at each age (Figure 7.2). For example:

- At age 10-11, 92% of boys and girls said that they would seek help from a parent, compared to only 70% of boys and 63% of girls at age 14-15.

- At age 10-11, 54% of boys and 68% of girls they would seek help from a friend if they had a problem, while at age 12-13, 63% of boys and 83% of girls said they would seek help from a friend.

- Willingness to seek help from a teacher was most common at age 10-11, when 45% of boys and 40% of girls reported they would do so. By age 14-15, only around a third of boys and 28% of girls said they would be willing to seek help from a teacher.

Note: a Comprises only those who reported having siblings, 10-11 years: n = 3,127 (91.8%) and 12-13 years: n = 3,060 (90.3%).

Source: LSAC Waves 4 and 5, K cohort, weighted

Notes: a Only adolescents who indicated they have had any emotional or personal problems in the last 12 months were reporting on past help-seeking behaviours. b Comprises only those who reported ever having a boyfriend or girlfriend, n = 1,657 (49.6%). c Comprises only those who reported having a boyfriend or girlfriend at the time of interview, n= 498 (15.4%). d Comprises only those who reported having siblings, n = 2,949 (88.2 %).

Source: LSAC Wave 6, K cohort, weighted

Figure 7.2: Willingness to seek help from parents, family, friends and teachers across three time points, by gender

Note: a Parents excluded.

Source: LSAC Waves 4, 5 and 6, K cohort, weighted

Help-seeking behaviours and intentions at age 14-15 years

Not every adolescent reports experiencing emotional or personal problems but a vast majority do (Table 7.3). About 91% of 14-15 year old girls and 81% of 14-15 year old boys reported having any emotional or personal problems within the past 12 months. When adolescents do have a problem, they might seek help from formal, informal or non-face-to-face sources (e.g. internet, phone helpline), though there can be discrepancies between adolescents' intentions to seek help and their actual help-seeking behaviour (Rickwood et al., 2005). Therefore, in order to fully understand adolescents' help-seeking behaviour, measuring both their behaviour and their intentions can be beneficial.

Source: LSAC Wave 6, K cohort, weighted

Box 7.2: Help-seeking behaviour and intentions at 14-15 years of age

At Wave 6, comprehensive data were collected on adolescents' help-seeking behaviours in the past 12 months, as well as their help-seeking intentions in the next four weeks. Based on this data, adolescents were classified as having demonstrated:

- formal help-seeking behaviours if they responded 'yes' to seeking help in the past 12 months from any formal source (teacher, other school staff, family doctor/GP, mental health professional)

- informal help-seeking behaviours if they responded 'yes' to seeking help in the past 12 months from any informal source (boyfriend/girlfriend, friend, parent, brother/sister, other relative/family member, other adult)

- non-face-to-face (non-F2F) help-seeking behaviours if they responded 'yes' to seeking help in the past 12 months from any non-F2F source (internet, phone helpline).

These categories are not mutually exclusive, as adolescents may seek help from multiple formal, informal or non-F2F sources.

Similar categories were created for adolescents' help-seeking intentions. Those who said they 'definitely would' or 'probably would' seek help from any formal/informal/non-F2F source in the next four weeks were considered to have formal/informal/non-F2F help-seeking intentions respectively.

Overall, around 37% of adolescents reported seeking help from any formal source in the past 12 months, while 40% said it was likely that they would seek formal help if they had a personal or emotional problem in the next four weeks (Table 7.4). Compared to formal sources such as mental health professionals, seeking help from informal sources such as a friend, sibling or parent, was more common among adolescents. Around 95% reported that they did seek help and 89% said that they would seek help from an informal source. Non-F2F help seeking was the least common help-seeking strategy (21% in the past 12 months and 23% in the next four weeks).

At age 14-15, there were some gender differences in adolescent help-seeking behaviours (Table 7.4). Girls generally reported more help-seeking behaviours and intentions than boys across formal, informal and non-F2F help sources. Still, it appears that the majority of 14-15 year olds did seek some type of help when they needed it, with 97% of girls and boys reporting that they sought some type of formal, informal or non-F2F help in the last 12 months for personal or emotional problems; and 95% of girls and 89% of boys saying they would be willing to seek help if they had a personal or emotional problem in the next four weeks.

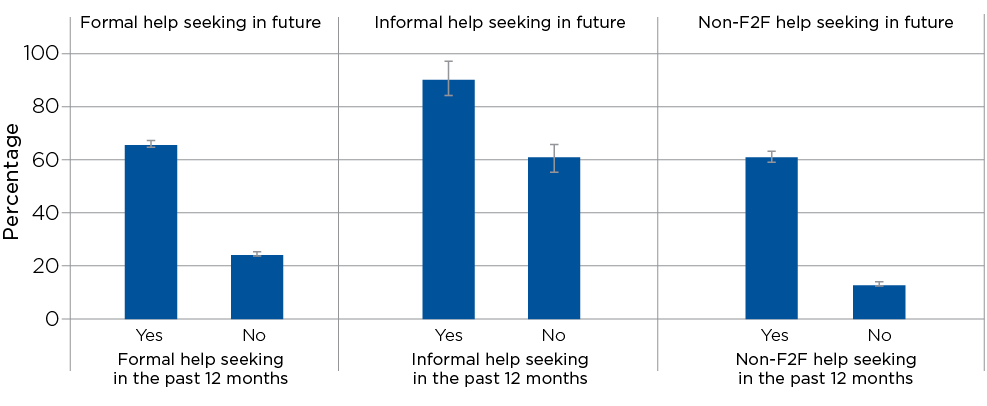

Adolescents with emotional or personal problems who sought formal, informal, or non-F2F help in the past 12 months also indicated that they were more likely to seek help via the same source in the next four weeks (Figure 7.3). Around 70% of adolescents with emotional or personal problems who used formal help sources in the past 12 months reported that they would use a formal help source in the next four weeks if they were to have a problem. This was compared to only 25% of adolescents who had an emotional problem in the last 12 months but had not used any formal help sources.

Compared to those who had not used non-F2F help in the past 12 months, those who had were also more likely to say they would use a non-F2F help source in the next four weeks if they had a problem (10% vs 60%). Similarly, adolescents who had used informal help for an emotional or personal problem in the last 12 months were more likely to use this source in future (90%) than those who had not sought help from their friends and families in the past. The results were similar for boys and girls.

Notes: Help-seeking behaviours are not mutually exclusive. Differences are statistically significant if confidence intervals do not overlap.

a Only adolescents who indicated that they have had any emotional or personal problems in the last 12 months were reporting on past help-seeking behaviours.

Source: LSAC Wave 6, K cohort, weighted

Figure 7.3: Future help-seeking behaviours based on past help-seeking behaviours

Notes: Only adolescents who indicated that they have had any emotional or personal problems in the last 12 months were reporting on past help-seeking behaviours. Help-seeking behaviours are not mutually exclusive. Differences are statistically significant if confidence intervals do not overlap.

Source: LSAC Wave 6, K cohort, weighted

7.2 Help seeking in adolescents with symptoms of mental health difficulties

Anxiety and depression are two of the most common mental health disorders experienced by Australian children and adolescents. Among young people aged 12-17, 7% experience an anxiety disorder, while 5% experience a major depressive disorder (Lawrence et al., 2015). Many more young people experience symptoms that do not meet the threshold for clinical diagnosis of these conditions. Rates of self-harm are also alarming among Australian adolescents, with one in ten 12-17 year olds reporting that they have ever self-harmed (Lawrence et al., 2015).

Adolescents experiencing symptoms of mental health difficulties are those most often in need of help and support. Understanding who these adolescents go to for help for their personal and emotional problems can help to identify opportunities to promote help seeking and better inform pathways to professional services (Rickwood et al., 2007). Some studies (e.g. Sheffield, Fiorenza, & Sofronoff, 2004) found that, compared to adolescents with no signs of psychological distress, those experiencing psychological distress are more likely to seek help, while other studies (e.g. Wilson, Rickwood, & Deane, 2007) found the opposite was true.

Box 7.3: Mental health difficulties

At age 14-15 (Wave 6), the LSAC K cohort reported on various aspects of their mental health, including symptoms of depression and anxiety and their history of self-harm.

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (Angold et al., 1995).

Anxiety symptoms were measured using the Spence Children's Anxiety Scale (Spence, 1998).

On both measures, adolescents can be categorised as either having symptoms or having no symptoms of these mental health difficulties.

Self-harm was measured using a single item on which adolescents indicated whether they had hurt themselves on purpose in any way in the past 12 months.

Depression

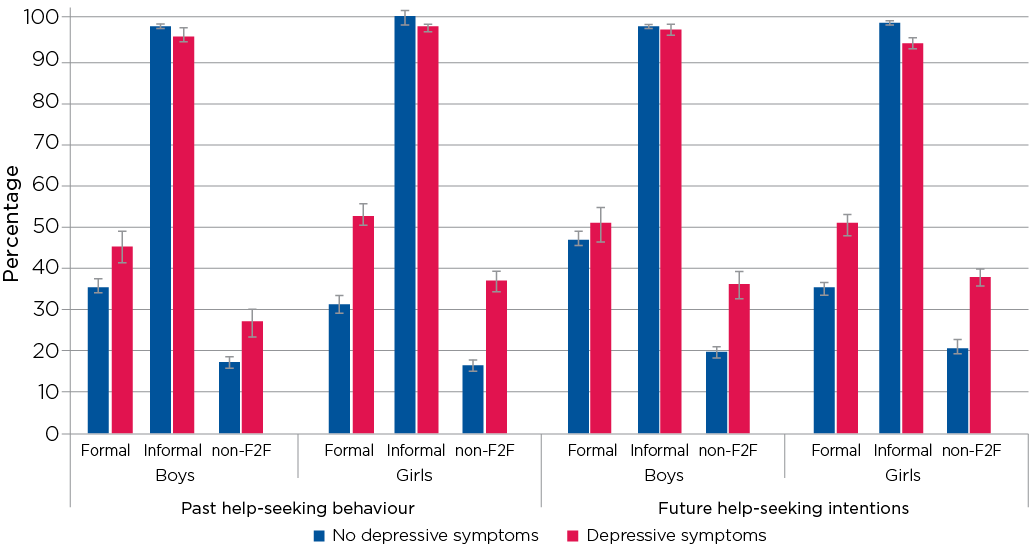

Depressive symptoms were reported by 26% of all 14-15 year olds, with 19% of boys and 34% of girls reporting symptoms. Overall, 91% of adolescents with symptoms of depression reported seeking help (from any source) for a personal or emotional problem in the last 12 months, compared to 81% of those with no symptoms (Table 7.5). Similar proportions of adolescents with and without symptoms, 90% and 92% respectively, reported intentions to seek help if they had a personal or emotional problem in the next four weeks. The differences were statistically significant.

Compared to those with no symptoms of depression, a higher proportion of adolescents with symptoms of depression reported seeking help from formal and non-F2F sources in the previous 12 months (Table 7.6). For example, 51% of 14-15 year olds with symptoms of depression reported seeking formal help and 33% reported seeking non-F2F help, while only 33% of those without symptoms of depression reported seeking formal help and 17% sought non-F2F help.

It was also more common for adolescents with symptoms of depression, compared to those with no symptoms, to say that it was likely that they would seek formal help (50% with symptoms versus 41% without symptoms) and non-F2F help (37% with symptoms versus 20% without symptoms) if they had a personal or emotional problem in the next four weeks. However, there was no difference in informal help seeking between adolescents with and without symptoms of depression. Informal help seeking was preferred by the majority of adolescents.

Overall, a larger proportion of girls with depressive symptoms reported seeking help, compared to boys with depressive symptoms (Figure 7.4). For example, among adolescents with symptoms of depression, 52% of girls and 45% of boys reported seeking formal help; and 37% of girls and 27% of boys reported seeking non-F2F help.

Source: LSAC Wave 6, K cohort, weighted

Note: a Only adolescents who indicated that they have had any emotional or personal problems in the last 12 months were reporting on past help-seeking behaviours.

Source: LSAC Wave 6, K cohort, weighted

Figure 7.4: Help-seeking behaviours and intentions of adolescents with and without symptoms of depression at age 14-15, by source and gender

Notes: Only adolescents who indicated that they have had any emotional or personal problems in the last 12 months were reporting on past help-seeking behaviours. Differences are statistically significant if confidence intervals do not overlap.

Source: LSAC Wave 6, K cohort, weighted

Anxiety

Symptoms of anxiety were reported by 16% of all 14-15 year olds, with 8% of boys and 25% of girls reporting symptoms. Patterns of help seeking among adolescents with and without symptoms of anxiety are similar to those for depressive symptoms (Table 7.7). Overall, 93% of adolescents with anxiety symptoms reported seeking help (from any source) in the last 12 months, compared to 82% of those with no anxiety symptoms. A similar proportion of adolescents with and without anxiety symptoms, 93% and 92% respectively, reported intentions to seek help if they had personal or emotional problems in the next four weeks.

Source: LSAC Wave 6, K cohort, weighted

Compared to adolescents with no anxiety symptoms, more adolescents with anxiety symptoms reported past help seeking from either formal or non-F2F sources (Table 7.8). For example, 51% of those with anxiety symptoms, and 35% of those without, reported formal help seeking; while 36% of those with anxiety symptoms, and 18% of those without, reported non-F2F help seeking.

Adolescents with symptoms of anxiety also more commonly reported willingness to seek help than those without symptoms if they had personal and emotional problems in the next four weeks from formal sources (48% with symptoms versus 43% without) and non-F2F sources (39% of those with symptoms versus 22% of those without). A similar proportion of adolescents with and without anxiety symptoms, 93% and 98% respectively, reported they would seek informal help in the next four weeks. Similar proportions of males and females with anxiety (95% and 90% respectively) reported willingness to seek help from informal sources in the future (Figure 7.5).

Note: a Only adolescents who indicated that they have had any emotional or personal problems in the last 12 months were reporting on past help-seeking behaviours.

Source: LSAC Wave 6, K cohort, weighted

Figure 7.5: Help-seeking behaviours and intentions of adolescents with and without symptoms of anxiety at age 14-15, by source and gender

Notes: Only adolescents who indicated that they have had any emotional or personal problems in the last 12 months were reporting on past help-seeking behaviours. Differences are statistically significant if confidence intervals do not overlap.

Source: LSAC Wave 6, K cohort, weighted

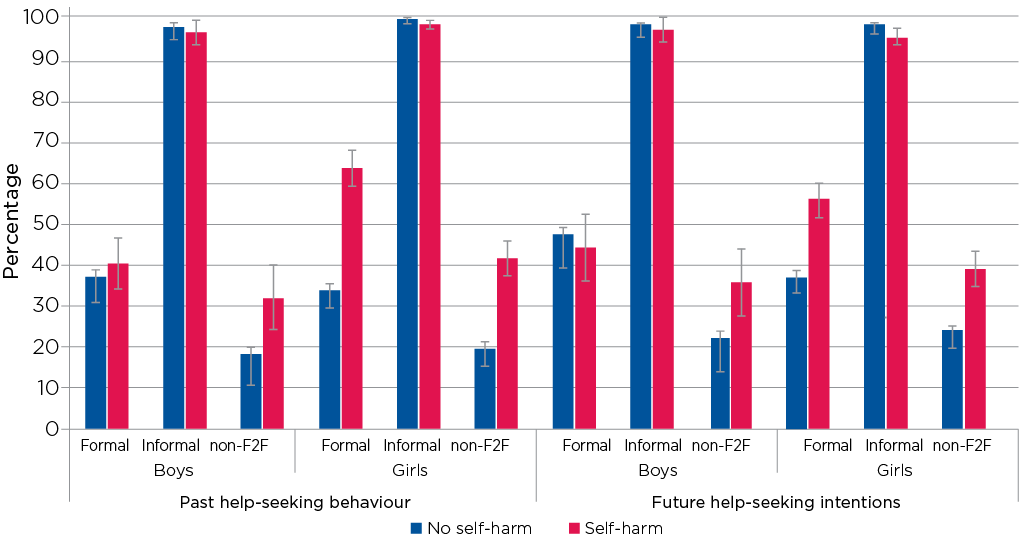

Self-harm

Almost 10% of all 14-15 year olds reported self-harming in the past 12 months, with 4% of boys and 15% of girls reporting an act of self-harm. Patterns of help seeking among adolescents who had self-harmed are similar to those for depression and anxiety (Table 7.9). Overall, 95% of adolescents who had self-harmed reported seeking help from any source in the last 12 months, compared to 82% who had not self-harmed.

A similar proportion of adolescents who had (93%) and had not (92%) self-harmed reported intentions to seek help (from any source) if they had personal or emotional problems in the next four weeks (Table 7.9). Compared to adolescents who had not self-harmed in the last 12 months, more adolescents who had self-harmed reported having sought help from formal and non-F2F sources (Table 7.10). For example, more than half of those who self-harmed (58%) reported seeking formal help, compared to 35% of those who had not self-harmed.

Adolescents who had self-harmed also more commonly reported that they would seek formal help (54% versus 42% of those who had not) and non-F2F help (38% versus 23% of those who had not) if they had a personal or emotional problem in the next four weeks. Rates of past informal help seeking were similar across adolescents who had and had not self-harmed.

As was the case for girls with symptoms of depression or anxiety, girls who reported having self-harmed were more likely to seek formal help than boys; that is, 63% of girls and 40% of boys sought help formally in the last 12 months (Figure 7.6). However, there was no significant gender difference in informal non-F2F help seeking among adolescents who had self-harmed, with 32% of boys and 41% of girls who reported having self-harmed in the past 12 months saying that they had sought non-F2F help, and around 95% of boys and girls saying they sought informal help in the past 12 months. Gender differences in help-seeking intentions, according to whether they had self-harmed in the past 12 months, were similar to those for help-seeking behaviour.

Source: LSAC Wave 6, K cohort, weighted

Note: a Only adolescents who indicated that they have had any emotional or personal problems in the last 12 months were reporting on past help-seeking behaviours.

Source: LSAC Wave 6, K cohort, weighted

Figure 7.6: Help-seeking behaviours and intentions of adolescents who have and have not harmed at age 14-15, by source and gender

Notes: Only adolescents who indicated that they have had any emotional or personal problems in the last 12 months were reporting on past help-seeking behaviours. Differences are statistically significant if confidence intervals do not overlap.

Source: LSAC Wave 6, K cohort, weighted

7.3 Predictors of formal, informal and non-F2F help-seeking behaviour

Two factors that have been shown to influence adolescents' help-seeking behaviours are gender and the presence of mental health difficulties. However, there are also a range of other factors that can influence adolescents' decisions about seeking help when they have a problem. The availability of adequate social support such as close relationships with peers and family may be one such factor. Previous research suggests that adolescents with greater levels of self-perceived social support (e.g. from family and friends) may be more likely to seek help from their informal networks, compared to those who experience less supportive relationships (Rickwood & Braithwaite, 1994; Sheffield et al., 2004). While some early evidence suggests that adolescents with more close friends may indeed be less likely to seek professional help (Sherbourne, 1988), other studies have found no relationship between social support and formal help seeking (Rickwood & Braithwaite, 1994; Sheffield et al., 2004). It will be useful to better understand which factors, among the range of factors associated with adolescent help seeking, are the best predictors of formal, informal and non-F2F help seeking.

Table 7.11 shows that the odds of seeking formal help for personal or emotional problems in the past 12 months were:

- two times higher for adolescents who had a history of self-harming (in the last 12 months) compared to those who had not self-harmed

- 1.6 times higher for adolescents with symptoms of depression and 1.4 times higher for adolescents with symptoms of anxiety, compared to those with no symptoms.

Adolescents who had experienced self-harm in the past 12 months and had good relationships with parents and peers were more likely to seek formal help in the next four weeks if they have a personal or emotional problem than those with no mental health symptoms and poor relationships with others. Compared to boys, girls were less likely to report seeking formal help in the next four weeks. The odds of adolescents reporting that they would seek formal help in the next four weeks were:

- 1.4 times higher for adolescents with a history of self-harming in the last 12 months compared to those who had not self-harmed

Notes: Odds ratios (OR) are shown. * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001. n.i. = not included. a SEP = socio-economic position.

Source: LSAC Wave 6, K cohort, weighted

- 30 percentage points lower for females compared to males

- 1.8 times higher for adolescents with good peer relationships and 1.4 times higher for adolescents with good parent relationships, compared to those with poor relationships

- 5.1 times higher for adolescents who sought formal help in the past 12 months compared to those who did not seek formal help in the past.

Informal help seeking in the past 12 months was more often reported by girls than boys, adolescents with symptoms of depression than without any depressive signs, and among those in a relationship at the time of interview. In particular, the odds of adolescents seeking informal help for personal or emotional problems in the past 12 months were:

- 1.5 times higher for adolescents with symptoms of depression compared to those with no symptoms

- 1.8 times higher for girls than boys

- 2.4 times higher for adolescents who were in a relationship at the time of the interview.

Compared to boys and adolescents with poor relationships with others, girls and adolescents with good relationships with parents and peers were also more likely to seek informal help for personal or emotional problems in the next four weeks. Adolescents' intentions to seek informal help were:

- 1.7 times higher for girls than boys

- 2.8 times higher for adolescents with good relationships with their parents and 2.5 times higher for adolescents with good relationships with their peers, compared to those with poor relationships

- 2.6 times higher for adolescents who sought informal help in the past 12 months compared to those who did not seek informal help.

Non-F2F help-seeking behaviour was more common among adolescents with mental health symptoms, from higher socio-economic background and who were in a relationship at the time of the interview, compared to those with no mental health symptoms, from low socio-economic background and without a boyfriend/girlfriend. Compared to adolescents with poor relationship with parents, adolescents with good relationships with parents were less likely to use non-F2F help seeking in the past 12 months. The odds of adolescents seeking non-F2F help for personal or emotional problems in the past 12 months were:

- 1.7 times higher for adolescents who have a history of self-harming, compared to those who have not self-harmed

- 1.7 times higher for adolescents with symptoms of depression and 1.6 times higher for adolescents with anxiety symptoms, compared to those with no symptoms

- 1.5 times higher for adolescents from a high socio-economic background compared to adolescents from a low socio-economic background

- 20 percentage points lower for adolescents with a good relationship with parents

- 1.4 times higher for adolescents who are currently in a relationship.

Table 7.11 also shows that, after accounting for other factors, the odds of adolescents reporting they would seek non-F2F help in the next four weeks were:

- 1.4 times higher for adolescents with symptoms of depression compared to those with no symptoms

- 30 percentage points lower for adolescents with a good relationship with parents

- 1.5 times higher for adolescents with good peer relationships, compared to those with poor relationships

- 8.5 times higher for adolescents who sought non-F2F help in the past 12 months compared to those who did not seek non-F2F help.

Summary

This chapter has provided a picture of the help-seeking behaviours and intentions of Australian adolescents aged from 10-11 to 14-15 years. The LSAC data show that the majority of adolescents who reported having a personal or emotional problem did seek help (97%); and 91% would seek help for personal or emotional problems in the future, whether that be from a formal, informal or non-F2F source.

Informal sources, such as family and friends, were the most common sources of help for adolescents, though as adolescents grow older fewer adolescents reported seeking help from parents (90% at 10-11 years old vs 69% at 14-15 years old). Also, if adolescents with emotional or personal problems used formal or non-F2F help sources in the previous 12 months, they were more likely to use the same sources in the immediate future.

This chapter confirms previous research on the association between adolescent help seeking and gender, mental health difficulties and social support. Adolescents with mental health difficulties were found to be more likely to seek help than those without such difficulties. However, when considering informal help seeking, the presence of mental health difficulties is more strongly associated with past help-seeking behaviours than with adolescents' reports of willingness to seek help in the future. For both formal and informal help sources, adolescents with higher levels of self-perceived social support from peers and parents are more willing to seek help in the future than those with inadequate social support.

The chapter raises a number of questions that will be important lines of enquiry for future work and which will help to directly inform practice and policy around adolescent help seeking for mental health difficulties.

References

Angold, A., Costello, E. J., Messer, S. C., Pickles, A., Winder, F., & Silver, D. (1995). Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. International Journal Of Methods In Psychiatric Research, 5, 237-249.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2014). Mental Health services - in brief 2014. Cat.no. HSE 154. Canberra: AIHW.

Belfer, M. L. (2008). Child and adolescent mental disorders: The magnitude of the problem across the globe. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(3), 226-236.

Kauer, S. D., Mangan, C., & Sanci, L. (2014). Do online mental health services improve help-seeking for young people? A systematic review. Journal Of Medical Internet Research, 16(3), e66-e66. doi:10.2196/jmir.3103

Lawrence, D., Johnson, S., Hafekost, J., de Haan, K. B., Sawyer, M., Ainley, J., & Zubrick, S. R. (2015). The mental health of children and adolescents. Report on the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Canberra: Department of Health.

Nicholas, J. (2004). Help-seeking behaviour and the Internet : An investigation among Australian adolescents. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 3(1), 1-8.

Raviv, A., Sills, R., & Wilansky, P. (2000). Adolescents' help-seeking behaviour: The difference between self- and other-referral. Journal of Adolescence, 23(6), 721-740. doi:10.1006/jado.2000.0355

Rickwood, D., Deane, F. P., Wilson, C. J., & Ciarrochi, J. (2005). Young people's help-seeking for mental health problems. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 3, 218.

Rickwood, D. J., & Braithwaite, V. A. (1994). Social-psychological factors affecting help-seeking for emotional problems. Social Science & Medicine, 4, 563.

Rickwood, D. J., Deane, F. P., & Wilson, C. J. (2007). When and how do young people seek professional help for mental health problems? The Medical Journal Of Australia, 187(7 Suppl.), S35-S39.

Sen, B. (2004). Adolescent propensity for depressed mood and help seeking: Race and gender differences. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 7(3), 133-145.

Sheffield, J. K., Fiorenza, E., & Sofronoff, K. (2004). Adolescents' willingness to seek psychological help: Promoting and preventing factors. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 33(6), 495-507.

Sherbourne, C. D. (1988). The role of social support and life stress events in use of mental health services. Social Science & Medicine, 27(12), 1393-1400.

Spence, S. H. (1998). A measure of anxiety symptoms among children. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(5), 545-566.

Steinberg, L. (2005). Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9, 69-74. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.005

Wilson, C., Rickwood, D., & Deane, F. (2007). Depressive symptoms and help-seeking intentions in young people. Clinical Psychologist, 11(3), 98-107. doi:10.1080/13284200701870954

Acknowledgements

Featured image: © GettyImages/Asiseeit