5. Teenagers and sex

5. Teenagers and sex

Key messages

As young people move from early to late adolescence, they develop both physically and psychologically, which also includes their sexual development. During this time, teens experience and explore different feelings and behaviours as aspects of their sexual growth. They may also begin dating which, while often short-lived, plays an important role in their day-to-day lives and ongoing development of how they see themselves and their exploration of sexual identity (Furman, Ho, & Low, 2007; Furman & Schaffer, 2003; Meier & Allen, 2009).

Many young people may not become sexually active until their late teenage years (Fisher et al., 2019); however, exploring sexual feelings, including thinking and talking about them, can occur much sooner. At this time, teenagers receive different information from parents, peers, social media and the internet about sex. This can shape their attitudes about sex and can influence their own sexual behaviours (Marston & King, 2006).

How young people approach their sexual development is personal, and so understanding their own sexuality and making informed decisions about their behaviours is essential for healthy sexual development into adulthood (Frayser, 1994). Parents and schools can play a pivotal role to enable a supportive environment so that teenagers can explore their feelings and behaviours in a respectful way for themselves and towards each other (Albert, 2007; Department for Education and Child Development, 2013; Dittus et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2011).

This important period in young people's sexual and psychosocial development - and the supportive role that parents and schools can play - is increasingly recognised with the delivery of respectful relationships education in schools and other child-focused settings.1

This chapter provides a snapshot of insights into sexual experiences and behaviours of teenagers aged 14-17 years. This includes sexual attraction and relationships, sexual intercourse, contraception choices, pornography viewing, and unwanted sexual behaviours.

5.1 Sexual attraction and relationships

From late childhood into early adolescence, many teenagers start to explore and discover their sexuality and who they are attracted to. Throughout this time teenagers can also start dating. In adolescence, sexual attraction and feelings are not always aligned - an adolescent primarily attracted to girls may also have sexual contact with boys and may or may not identify as heterosexual, lesbian, gay, bisexual or other sexual-orientation groups (e.g. asexual, pansexual, demisexual). This fluidity may be true of both adolescents and adults, and is reported more frequently by girls (Perales & Campbell, 2019).

Box 5.1: Sexual attraction

At the age of 14-15, LSAC study participants (K cohort, 2014) were asked, 'Which of these statements best describes your sexual feelings at this time in your life:

- I'm attracted only to girls

- I'm attracted only to boys

- I'm attracted to girls and boys

- I'm not sure who I am attracted to

- I don't feel any attraction to others.'

Note: Sexual orientation might change as children grow up, but 16-17 year olds were not asked who they were attracted to.

Adapted from the Ten to Men study, Wave 1 (2013).

At the age of 14-15, LSAC children were asked about their sexual attraction (Box 5.1):

- The majority (93% of boys and 85% of girls) reported being attracted only to the opposite sex.

- Two per cent of boys and 4% of girls said that they were attracted to both boys and girls.

- Less than 1% said they were attracted only to people of the same sex.

- Some teenagers were still in the process of understanding their sexual identity, with 2% of girls and 4% of boys reporting that they were not sure who they were attracted to, and 5% of girls and 4% of boys reporting that they were not attracted to anyone.

Box 5.2: Relationships

In Wave 6, when the LSAC K cohort children were aged 14-15, they were asked if they currently have a boyfriend or girlfriend.

At age 16-17, study children were asked if they currently have a boyfriend or girlfriend, and whether they had gone out with anyone since their last LSAC interview.

Those 16-17 year olds who said that they currently have a boyfriend or girlfriend were asked:

- 'How do you regard your relationship?' (The options were 'Casual', 'Exclusive/committed', 'Engaged to be married' and 'Married'.)

- 'Do you and your boyfriend/girlfriend that you feel more serious about or have been going out with the longest, regularly stay over at each other's place?'

Adapted from the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study, Age 32 Assessment phase.

From 14-15 years old LSAC young people were asked whether they had a boyfriend or girlfriend. Around one in seven 14-15 year olds (15% of boys and 16% of girls) said they had a boyfriend or girlfriend at the time of the interview. Among those who had a boyfriend or girlfriend (n = 673), most (81% of boys and 77% of girls) said that they went out together to places such as the movies, without anyone else.

By the age of 16-17, around two-thirds (67% of boys and 62% of girls) reported having had at least one relationship. One in five boys and one in four of girls said that they currently had a boyfriend or girlfriend (n = 673). This is slightly lower than statistics reported in the National Survey of Secondary Students and Sexual Health (Fisher et al., 2019). According to this survey, in 2018, around 77% of 14-18 year olds reported having a relationship at some point in their lives but only around 40% reported being in a relationship at the time of the survey.

Among those 16-17 year olds who reported having a boyfriend or girlfriend in the LSAC survey:

- Around 4% reported dating someone of the same sex.

- More than four in five (84%) considered that they were in committed/exclusive relationships while the rest considered their relationships casual.

- Around half (51%) reported regularly staying over at each other's place.

Figure 5.1: By the age of 16-17, two thirds of teenagers had been involved in a romantic relationship

5.2 Sexual behaviours

While the majority of LSAC children at age 16-17 reported having a boyfriend or girlfriend, a much smaller proportion reported being sexually active.2 It is worth acknowledging that sexual behaviours are not limited to sexual intercourse but also include genital touching, deep kissing and oral sex (although LSAC respondents were not asked about these behaviours).

Box 5.3: Sexual intercourse

In Waves 6 and 7 of LSAC, when the K cohort children were aged 14-15 and 16-17, they were asked if they had ever had sex (with the question specifying 'by sex we mean sexual intercourse').

Those who said they had had sex at least once were asked how old they were the first time they had sex.

Adapted from the WA Child Health Survey: Youth Self-report (15–16 years).

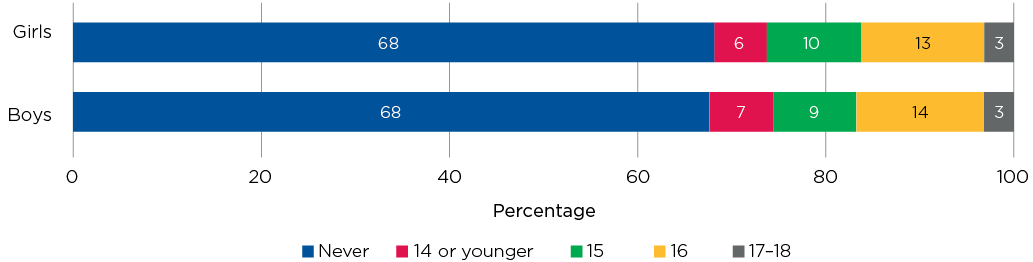

At the age of 16-17 years old, two thirds (68%) reported they had not yet had sexual intercourse by this age, with no significant differences in the age that girls and boys had sex for the first time:

- Just over one in 15 (7% of boys and 6% of girls) said that they had sex for the first time at age 14 or younger.

- Around one in 10 (9% of boys and 10% of girls) said they first had sex at age 15.

- One in six (17% of boys and 16% of girls) reported having sex for the first time at age 16 or 17 (Figure 5.2).

Adapted from the WA Child Health Survey: Youth Self-report (15–16 years).

According to the 2018 National Survey of School Student and Sexual Health, touching one's own genitals was the most common sexual behaviour (89%), followed by deep kissing (74%), being touched on the genitals (66%) or touching a partner's genitals (65%), and around half reported having engaged in oral sex at least once (Fisher et al., 2019).

Figure 5.2: Age first had sexual intercourse, 16-17 year olds in 2016

Notes: n = 1,469 boys and 1,434 girls. At Wave 7 interview, 54.4% of the study children in the K cohort were aged 16 years and 45.3% were aged 17 years. Ten children were aged 18 at the time of their Wave 7 interview.

Source: LSAC Wave 7, K cohort, weighted

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

5.3 Contraception and safe sex

Box 5.4: Contraception and prevention of sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

In Waves 6 and 7 of LSAC, study participants in the K cohort (aged 14-15 and 16-17) who reported having sex at least once were asked about the methods they had used to prevent pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections the last time they had sex.

In the question about methods used to prevent pregnancy, the options at age 14-15 (Wave 6) were: 'None', 'Birth control pills', 'Condoms', 'Other' and 'Not sure'.

At Wave 7 (age 16-17), a wider range of options was provided that included 'None', 'Birth control pills', 'Condoms', 'Morning after pill', 'Contraceptive implant', 'Contraceptive injection', 'Intrauterine device (IUD)', 'Diaphragm', 'Vaginal ring', 'Other', and 'Not sure'.

In the question about methods used to prevent sexually transmitted infections, the options were the same at ages 14-15 and 16-17: 'None', 'Condoms', 'Other' and 'Not sure'.

The sexual experience and contraception concepts were derived from the 2014 Ontario Child Health Study (OCHS) self-complete questionnaire.

Among teenagers who were sexually active, the majority were using either condoms or birth control pills to prevent pregnancies; and most were taking precautions to prevent sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (Table 5.1).

Of the 5% of 14-15 year olds who reported being sexually active in 2014:

- Three out of four (76% of boys and 73% of girls) said they had used a condom to prevent pregnancy the last time they had sex.

- While around one in three girls (30%) and one in 10 boys (10%) said that they (or their partner) had used birth control pills to prevent pregnancy. The number of observations was too small for these estimates to be considered reliable.

- Around three in four (75% of boys and 77% of girls) said they had used a condom to prevent STIs the last time they had sex.

- Almost one in five (19%) said they did not use any method to prevent STIs.

Among the 32% of 16-17 year olds who reported having had sexual intercourse at least once in 2016 (Table 5.1):

- Around three in four (78% of boys and 71% of girls) said that they had used a condom to prevent pregnancy the last time they had sex.

- Around one in four boys (27%) and one in two girls (46%) said that they (or their partner) had used birth control pills to prevent pregnancy.

Notes: na - not asked. #Estimate not reliable (cell count < 10). Due to very small numbers of observations, for methods used to prevent pregnancy, the following categories were not reported even at aggregated level: Contraceptive injection, Intrauterine device (IUD), Diaphragm, Vaginal ring. Asterisks (marked in the second column of each age group) indicate statistically significant differences in proportions between boys and girls, from chi-square tests: * p < .05, ** p <. 01, *** p < .001.

Source: LSAC Waves 6 & 7, K cohort, weighted

Other methods of birth control were less common:

- One in eight (13%) girls said they had used a contraceptive implant; and one in 12 (8%) boys said their partner had done so.

- Fewer than one in 10 (8% of boys and 6% of girls) said that they, or their partner, had used the morning after pill.

While around three quarters of 16-17 year olds who were sexually active said that they had used a condom to prevent STIs the last time they had sex - one in four girls (26%) and nearly one in five boys (17%) had not taken any action for prevention. This finding highlights the importance of sex education in schools that covers aspects of safe sex by understanding what is preventing young people from using contraception to prevent unplanned pregnancies and STIs.

5.4 Viewing pornography

A review of the literature on the effects of pornography on young people reveals that young people can use pornography for a number of reasons; that is, as a source of sex education, for entertainment or for sexual stimulation (Quadara, El-Murr, & Latham, 2017). Viewing pornography can affect young people's sexual attitudes, expectations and practices (Quadara, El-Murr & Latham, 2017). While viewing pornography might be part of young people's sexual experience, what is concerning is the wrong message it can give to young people about control, pleasure and physical aggression.

Box 5.5: Viewing pornography

At Wave 7 of LSAC, study children in the K cohort (age 16-17) were asked about viewing pornography. They were asked:

- How old were you when you started viewing pornography?

- In the past 12 months, how often did you view pornography?

- Who do you usually view pornography with?

Items on the age of first viewing pornography and frequency of pornography viewing were adapted from the Burnet Institute Big Day Out Study (2017).

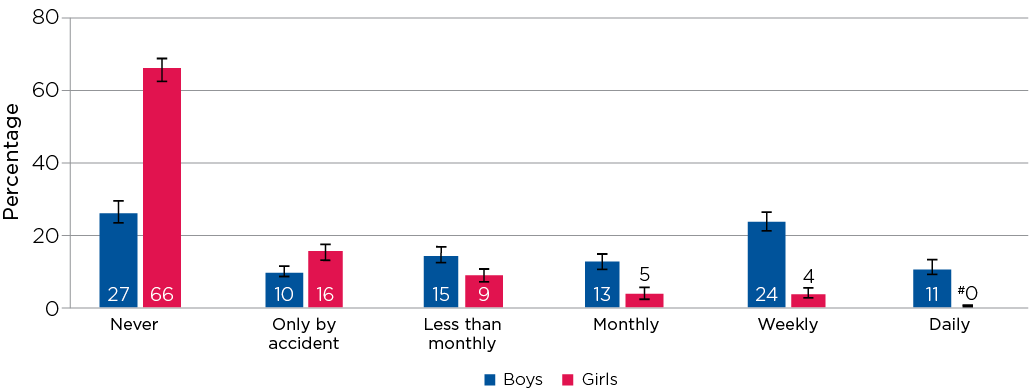

According to the LSAC data, at age 16-17, significantly more boys than girls had intentionally viewed pornography in the past 12 months; that is, almost three quarters of boys but only one in three girls saying they had viewed pornography in that time (Figure 5.3). Boys also reported viewing pornography far more frequently than girls:

- One in 10 boys (11%) and less than one in 100 girls (0.004%) said they watched pornography daily.

- One in four boys (24%) and less than one in 20 girls (4%) said they watched pornography weekly.

Among those who reported viewing pornography intentionally, the vast majority said that they usually did so alone. While it was less common for girls than boys to intentionally watch pornography; among those who did, it was more common for girls than boys to say that they viewed pornography with a partner or with friends:

- Around nine in 10 boys and girls (96% of boys and 90% of girls) said they usually viewed pornography alone.

- Around one in 30 boys (3%) and one in eight girls (13%) said they usually viewed pornography with their boyfriend, girlfriend or partner.

- One in 25 boys (4%) and one in 10 girls (10%) said that they usually watched pornography with friends.

- One in 50 boys and girls (2%) said they usually viewed pornography with people other than a partner or friend.

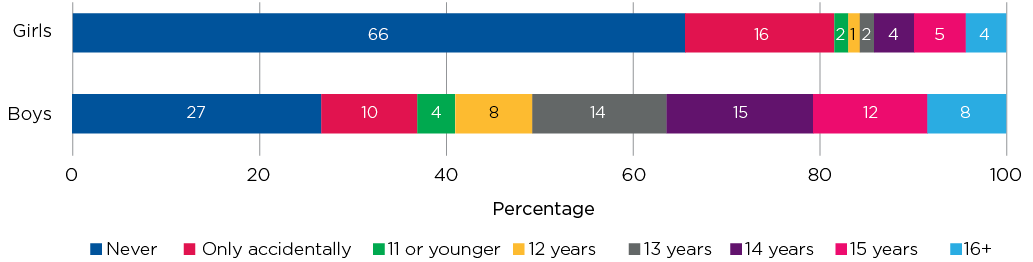

Boys also start viewing pornography at a younger age than girls. At 16-17 years, more than half of the boys (53%) and one in seven girls (14%) had viewed pornography intentionally before the age of 16 (Figure 5.4). Twelve per cent of boys and 3% of girls had viewed pornography before the age of 13; while 4% boys were aged 11 or younger when they had first seen pornography, compared to 2% of girls.

Teenagers who reported viewing pornography before the age of 15 years old were also more likely to report having sex for the first time before the age of 16 (23%) compared to teenagers who reported viewing pornography after they turned 15 (15% had sex before the age of 16) or who had never viewed pornography (11% had sex before the age of 16).

Figure 5.3: How often 16-17 year olds viewed pornography in past 12 months

Notes: #Estimate not reliable (cell count < 20). n = 1,446 boys and 1,437 girls. 95% confidence intervals are shown by the 'I' bars at the top of each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the differences in values within each category are statistically significant.

Source: LSAC Wave 7, K cohort, weighted

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Figure 5.4: Age first viewed pornography

Note: n = 1,430 boys and 1,434 girls.

Source: LSAC Wave 7, K cohort, weighted

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

5.5 Unwanted sexual behaviours

It is normal for young people to express their sexuality to others, but not all sexual behaviours are wanted or welcomed. 'An unwelcome sexual advance, unwelcome request for sexual favours or other unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature which makes a person feel offended, humiliated or intimidated, where a reasonable person would anticipate that reaction in the circumstances', often also referred to as sexual harassment, is of great concern among young people (Australian Human Rights Commission, 2003). As a teen, the experience of unwanted sexual behaviours can impair romantic relationships. It is also related to symptoms of depression and anxiety (Bendixen, Daveronis, & Kennair, 2018).

Box 5.6: Unwanted sexual behaviours

At age 16-17, the LSAC study children were asked about their experiences of unwanted sexual behaviours, both of being harassed themselves and whether they had sexually harassed someone else (adapted from Clear et al. (2014)). More specifically, they were asked how often, in the 12 months prior to their LSAC interview, they had:

Experienced unwanted sexual behaviours:

- Someone told, showed or sent sexual pictures, stories or jokes that made me feel uncomfortable.

- Someone made sexual gestures, rude remarks, used body language, touched, or looked at me in a way that embarrassed or upset me.

- Someone kept asking me out on a date or asking me to hook up although I said 'No'.

Engaged in unwanted sexual behaviours towards someone else:

- I told, showed or sent sexual pictures, stories or jokes that made someone feel uncomfortable.

- I made sexual gestures, rude remarks, used body language, touched, or looked at someone in a way that embarrassed or upset them.

- I kept asking someone out on a date, or asking them to hook up, although they said 'No'.

The LSAC data show that (Table 5.2):

- One in two girls (49%) and one in three boys (31%) said that they had experienced some form of unwanted sexual behaviours in the past 12 months, though the gender of the person who had done this was not reported.

- Around one in 12 girls (8%) and one in eight boys (12%) reported having engaged in sexually unwanted behaviours towards someone else in the past 12 months, though the gender of the person at who such behaviour was directed was not reported.

Note: n = 1,486 boys and 1,444 girls.

Source: LSAC Wave 7, K cohort, weighted

Of those who reported having engaged in unwanted sexual behaviour, most said they had done so once or twice. However, among the 8% of boys who said they had showed or sent sexual pictures, or told stories or jokes that made someone feel uncomfortable, almost a quarter said they had done it three times or more in the past 12 months. Of the 7% of boys who reported that they had made sexual gestures, rude remarks, used body language, touched, or looked at someone in a way that embarrassed or upset them, one in five said they had done so three times or more in the past 12 months.

5.6 Pornography and unwanted sexual behaviours

Studies have shown that boys who view pornography are more likely to engage in verbal and physical sexual aggression (Wright, Tokunaga, & Kraus, 2015). A 2012 review of the effect of internet pornography on adolescents found that adolescents who are intentionally exposed to violent sexually explicit material were six times more likely to be sexually aggressive than those who were not exposed (Owens, Behun, Manning, & Reid, 2012). Another study found exposure to pornography was associated with greater acceptance of stereotyped and sexist notions about gender and sexual roles, including notions of women as sexual objects (Peter & Valkenburg, 2007).

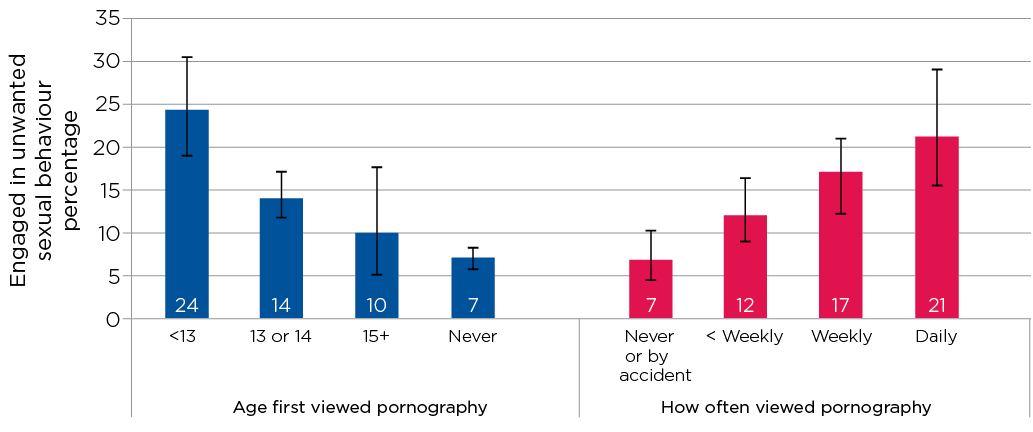

The LSAC data show that the percentage of boys who reported unwanted sexual behaviours in relation to someone else at the age of 16-17 was significantly higher among those who had viewed pornography for the first time before the age of 13 compared to boys who said they had never viewed pornography; that is, one in four (24%) versus less than one in 10 (7%) (Figure 5.5).3

How often boys viewed pornography at age 16-17 was also associated with unwanted sexual behaviours (Figure 5.5). Among boys who reported watching pornography daily, more than one in five (21%) reported engaging in unwanted sexual behaviour, compared to less than one in 10 (7%) of boys who said they had never viewed pornography in the previous 12 months, or had done so by accident.

Figure 5.5: Association between viewing pornography and unwanted sexual behaviour, boys 16-17 years old

Notes: n = 2,838. 95% confidence intervals are shown by the 'I' bars at the top of each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the differences in values between age categories in the left graph and between frequencies of viewing pornography in the right graph are statistically significant.

Source: LSAC Wave 7, K cohort, weighted

Summary

Adolescence is an important time developmentally for teenagers in regard to their sexual behaviours and relationships. In the teenage years, young people are still exploring their sexual orientation; at age 14-15, while most reported being attracted only to the opposite sex, around 4% reported both or same-sex attraction.

As teenagers start exploring their sexual feelings and behaviours, they are likely to start dating - one in seven teenagers aged 14-15 reported having a boyfriend or girlfriend while two out of three reported being in a relationship by age 16-17.

By the age of 16-17, around one in three had engaged in sexual intercourse. These estimates are consistent with those of the Secondary Students Sexual Health Study, which showed that the age that Australian teenagers are first having sex has been declining and, in 2018, 34% of Year 10 students reported having had sexual intercourse (Fisher et al., 2019).

Estimates based on LSAC data show that most teenagers who were sexually active said they had used a condom to prevent sexually transmitted infections the last time they had sex; and research has shown that Australian secondary students are largely engaging in responsible behaviours and that they are accessing a diverse array of educational sources to learn about STIs (Fisher et al., 2019). However, of 16-17 year olds who were sexually active, around one in five said that they had done nothing to prevent sexually transmitted infections and around one in 12 said that they had done nothing to prevent pregnancy the last time they had sex.

Almost half of girls aged 16-17 and almost one third of boys said that they had experienced some form of unwanted sexual behaviours in the past 12 months; and one in 13 girls and one in eight boys reported having sexually harassed someone else during that time. Reports of engaging in unwanted sexual behaviours were significantly higher among boys who had viewed pornography for the first time before the age of 13, and those who viewed pornography daily at the age of 16-17.

Boys were much more likely than girls to have intentionally viewed pornography, and among those who did view pornography, boys did so much far more often than girls. More than half of boys aged 16-17 and one in seven girls had viewed pornography before the age of 16. There was a significant association between the age at which teenagers had viewed pornography for the first time and the age at which they had sex for the first time, with 26% of those who reported having seen pornography for the first time before the age of 13 having had sex before the age of 16.

Improvements to internet downloading speeds and the use of handheld smart devices have made accessing pornography easier, faster and more anonymous. Children and young people are accessing pornography at increasing rates, with boys aged 14-17 years being the most common underage consumers of pornographic material (Campo, 2016). In Australia, just under half (44%) of children aged 9-16 reported encountering sexual images in the last month; and younger children (aged 9-12) were particularly likely to be distressed or upset by pornography (Quadara, El-Murr, & Latham, 2017).

This chapter has provided insights into the sexual behaviours of teenagers, as well as their experiences with unwanted sexual behaviours and pornography. It highlights that it is important to have supportive conversations with children to empower them to make informed decisions about their sexual behaviours. For example, school sexual health education programs can support teenagers, using a whole-school approach to address respectful relationships, sexual orientation and navigating the online environment (including sexting and pornography).

References

Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC). (2003). A bad business: Legal definition of sexual harassment. Sydney: AHRC. Retrieved from www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/bad-business-fact-sheet-legal-definition...

Albert, B. (2007). With One Voice 2007: America's Adults and Teens Sound Off about Teen Pregnancy. A Periodic National Survey. Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy. Retrieved from success1st.org/uploads/3/4/5/1/34510348/wov_2012.pdf

Bendixen, M., Daveronis, J., & Kennair, L. E. O. (2018). The effects of non-physical peer sexual harassment on high school students' psychological well-being in Norway: Consistent and stable findings across studies. International Journal of Public Health, 63(1), 3-11.

Campo, M. (2016). Children and young people's exposure to pornography (CFCA Discussion Paper). Retrieved from aifs.gov.au/cfca/2016/05/04/children-and-young-peoples-exposure-pornography

Clear, E. R, Coker, A. L., Cook-Craig, P. G., Bush, H. M., Garcia, L. S., Williams, C. M. et al. (2014). Sexual harassment victimization and perpetration among high school students. Violence Against Women, 20(10), 1203-1219.

Department for Education and Child Development. (2013). Responding to problem sexual behaviour in children and young people: Guidelines for staff in education and care settings. Adelaide: DECD, Government of South Australia.

Dittus, P. J., Michael, S. L., Becasen, J. S., Gloppen, K. M., McCarthy, K., & Guilamo-Ramos, V. (2015). Parental monitoring and its associations with adolescent sexual risk behavior: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 136(6), e1587-e1599.

Fisher, C. M., Waling, A., Kerr, L., Bellamy, R., Ezer, P., Mikolajczak, G. et al. (2019). 6th National Survey of Australian Secondary Students and Sexual Health 2018 (ARCSHS Monograph Series No. 113). Bundoora: Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health & Society, La Trobe University.

Frayser, S. G. (1994). Defining normal childhood sexuality: An anthropological approach. Annual Review of Sex Research, 5(1), 173-217.

Furman, W., Ho, M. J., & Low, S. M. (2007). The rocky road of adolescent romantic experience: Dating and adjustment. In R. C. M. E. Engels, M. Kerr, & H. Stattin (Eds.), Friends, lovers and groups: Key relationships in adolescence (pp. 93-104). New York: Wiley.

Furman, W., & Shaffer, L. (2003). The role of romantic relationships in adolescent development. In P. Florsheim (Ed.), Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications (pp. 3-22). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Marston, C., & King, E. (2006). Factors that shape young peoples' sexual behaviour. The Lancet, 368(9547), 1581-1586.

Meier A., & Allen G. (2009). Romantic relationships from adolescent to young adulthood: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Social Quarterly, 50, 308-335

Owens, E., Behun, R., Manning, J., & Reid, R. (2012). The impact of internet pornography on adolescents: A review of the research. The Journal of Treatment & Prevention, 19(1-2).

Perales, F., & Campbell, A. (2019). How many Australians are not heterosexual? It depends on who, what and when you ask. The Conversation, June 11. Retrieved from theconversation.com/how-many-australians-are-not-heterosexual-it-depends-on-who-what-and-when-you-ask-118256

Peter, J. & Valkenburg, P. (2007). Adolescents' exposure to a sexualized media environment and their notions of women as sex objects. Sex Roles, 56(5-6), 381-395.

Quadara, A., El-Murr, A., & Latham, J. (2017). The effects of pornography on children and young people: An evidence scan (Research Report). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Smith, A., Schlichthorst, M., Mitchell, A., Walsh, J., Lyons, A., Blackman, P., & Pitts, M. (2011). Sexuality education in Australian secondary schools 2010 (Monograph Series No. 80). Melbourne: La Trobe University, the Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health & Society.

Wright, P. J., Tokunaga, R. S., & Kraus, A. (2015). A meta-analysis of pornography consumption and actual acts of sexual aggression in general population studies. Journal of Communication, 66(1), 183-205.

1 Over the last two decades, Respectful Relationships curricula have been developed and delivered in Australian schools as a key plank in reducing family, domestic and sexual violence. Under the fourth action plan to reduce violence against women and their children, two of the key national priorities are: implement community-led and tailored initiatives to respect, listen and respond to the diverse lived experience and knowledge of women and their children affected by violence; and respond to sexual violence and sexual harassment though specialised and consistent support as well as through targeted initiatives that promote informed consent, bodily autonomy and respectful relationships (for details see www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/08_2019/fourth_action-plan.pdf).

2 Being sexually active is defined as in Fisher et.al. (2019) - 'young people are defined sexually active if they had ever engaged in sexual intercourse (anal and/or vaginal sex)'.

3 Note that the analysis of associations between use of pornography and sexually unwanted behaviours was undertaken only for boys, as the number of observations for girls viewing pornography and reporting unwanted sexual behaviours were too small for reliable estimates.

Acknowledgements

Featured image: © GettyImages/Ales-A