11. Here to help: How young people contribute to their community

11. Here to help: How young people contribute to their community

Youth engagement and community involvement has benefits for communities and young people alike. While the narrative about young people has often focused on deficits and risk behaviours, messages coming out of the Positive Youth Development (PYD) field since the early 1990s have stressed the importance of thinking about young people in terms of their developmental potential and positive outcomes (Benson, Scales, & Syvertsen, 2011; Catalano, Hawkins, Berglund, Pollard, & Arthur, 2002; Lerner, Almerigi, Theokas, & Lerner, 2005a). Participation in community-based activities is a key outcome of PYD since youth with social and emotional skills, a strong sense of self-worth and supportive relationships are more likely to become involved in their communities (Lerner, Lerner et al., 2005). Youth participation in community activities and civil society is also part of the process of PYD: when young people contribute, they are engaged as a source of change for their own and for their communities' positive development (Hinson et al., 2016). One of the major ways that young people contribute to their community is through volunteering.

Australia has a strong culture of community volunteering - almost a third of Australian adults (5.8 million people) participated in voluntary work in 2014 (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2015a). In 2018, Australia was ranked sixth out of 146 countries worldwide for participation in volunteering activities (Charities Aid Foundation, 2018). The direct contribution of the volunteer workforce to the economy has been estimated at over $17 billion (ABS, 2015c) and broader social and economic benefits have been estimated to be as high as $200 billion (Volunteering Australia, 2015).

Volunteering is defined as 'the provision of unpaid help willingly undertaken in the form of time, service or skills, to an organisation or group, excluding work done overseas' (ABS, 2018).

As adolescents grow up, they are provided with volunteering opportunities that can enhance their mental and physical health (Moreno, Furtner, & Rivara, 2013; Schreier, Schonert-Reichl, & Chen, 2013) and improve social and academic outcomes (e.g. Elder & Conger, 2000; Moorfoot, Leung, Toumbourou, & Catalano, 2015). Beyond the direct contribution to the community, involvement in these activities is likely to benefit their development, personal growth, self-confidence and wellbeing, providing them with important life experiences and a feeling of being valued (e.g. Elder & Conger, 2000; Moreno et al., 2013). It allows adolescents to connect with new and different people, broadening their understanding of community diversity. The experiences and skills learned through voluntary activities can also strengthen a young person's career prospects (e.g. Walsh & Black, 2015) and volunteering has been associated with a lower involvement in crime (e.g. Ranapurwala, Casteel, & Peek-Asa, 2016).

There is little available data on youth volunteering in Australia, particularly under the age of 15 (Walsh & Black, 2015). Understanding volunteering trends in young people is important, given that there are clear individual and societal benefits. LSAC provides a unique opportunity to explore volunteering among young adolescents, and the association between parents' and children's involvement in volunteering activities. Using data collected in 2016, this chapter describes the types of voluntary activities that adolescents at 12-13 and 16-17 years and their parents participate in. The chapter also looks at the frequency and amount of time that adolescents spend volunteering, and the characteristics of adolescents who participate in these activities.

11.1 Participation in volunteering activities

Previous ABS data show that approximately two in five 15-17 year olds reported volunteering in 2014, which was the highest rate of involvement of all age groups. This group was most likely to participate in sport and physical recreation, education and training, welfare or community and religious group activities (ABS, 2015b).

Box 11.1: Volunteering activities and time spent volunteering

In Wave 7 of LSAC, study children in the B and K cohorts, aged 12-13 and 16-17, respectively, and their parents, were asked to indicate whether or not, in the last 12 months, they did any unpaid work for any of the following types of organisations:

- Church or religious groups

- Community or welfare organisations (e.g. Clean Up Australia, The Smith Family)

- School and children's groups (e.g. canteen, teacher's aide, play group, child care)

- Sport and recreation (e.g. coaching, refereeing)

- Arts, heritage, cultural or music activities (e.g. museum)

- Youth, student service, mentoring, leadership or adventure (e.g. scouts)

- Environment (e.g. conservation)

- Animal welfare (e.g. RSPCA)

- Emergency services (e.g. firefighting, search and rescue)

- Health or health care (e.g. volunteering in a hospital or clinic)

- Teaching or training (e.g. TAFE, community college, adult education classes)

- Immigrant or refugee assistance

- International aid or development (e.g. Oxfam)

- Law, justice, political or human rights (e.g. Amnesty International)

- Business or professional associations or unions

- Ethnic and ethnic-Australian societies

- Other

The questions were adapted from the Australian Bureau of Statistics General Social Survey (ABS, 2011).

At age 12-13 and 16-17 study participants who reported they had done some voluntary work were asked:

In the last 12 months, how often did you work for this organisation or these organisations on a voluntary basis?

Response options were: 'at least once a week', 'at least once a fortnight', 'at least once a month', and 'at least once a year'. Interviewers were instructed to classify voluntary work done over a block of time (e.g. a three-month period) as 'at least once a year'.

In total, how many hours did you do volunteer activities for this organisation or these organisations per week, fortnight, month or year?

Interviewers were instructed to enter whole hours. Hours given per week, fortnight or month were converted to number of hours per year.

The LSAC data in 2016 show that around four in 10 (43%) 12-13 year olds and over half (53%) of 16-17 year olds reported having participated in some type of voluntary work in the past year.

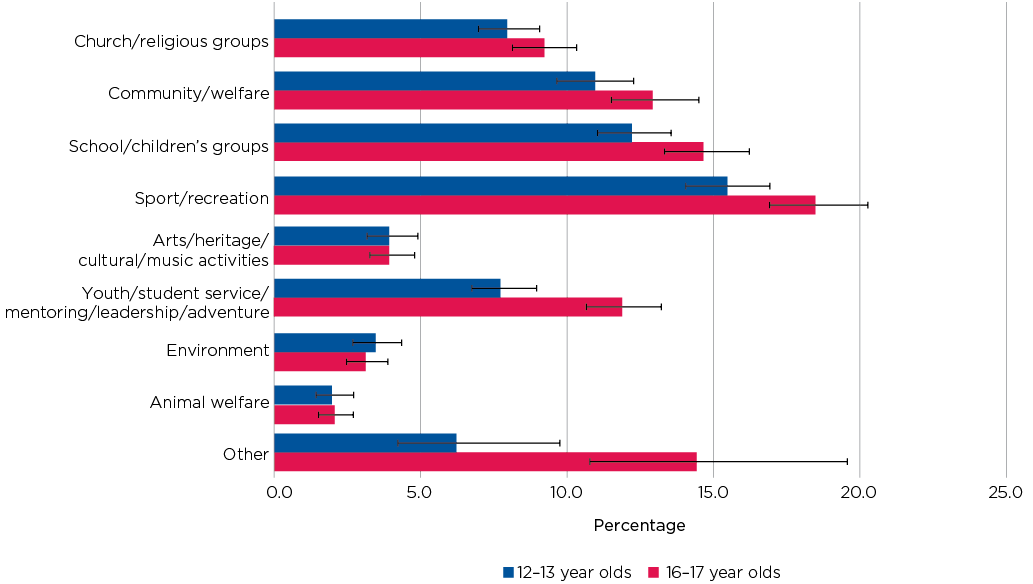

The most common types of volunteering activities, among 12-13 year olds and 16-17 year olds (Figure 11.1) were:

- sport and recreation - 16% at age 12-13 and 19% at age 16-17

- school and children's groups - 12% at age 12-13 and 15% at age 16-17

- community or welfare organisations - 11% at age 12-13 and 13% at age 16-17.

This may be because these types of volunteering activities are more readily available for young people at both age groups. Adolescents may also become involved in these activities at an early age and continue to participate in the same type of activities as they grow older. Additionally, adolescents might be connected to these activities through their schools or at least be encouraged by their schools to participate in these activities.

As adolescents become older, they may be more likely to take on leadership or mentoring roles while they decide on future education or employment opportunities (Figure 11.1). For example, more 16-17 year olds than 12-13 year olds participated in voluntary work related to youth, student service, mentoring, leadership or adventure (12% vs 8%). The LSAC data also show that more 16-17 year olds than 12-13 year olds volunteered for 'other' types of organisations (15% vs 6%), which may also suggest an increase in interest and opportunity to try a range of volunteering activities available to older adolescents. It is also likely that there are age restrictions for particular volunteering activities, limiting the choices of 12-13 year olds to participate in different volunteering activities.

Among those who volunteered, most (approximately three in five in both age groups) reported doing volunteer work for one organisation type.1 Around a quarter of adolescents volunteered for two organisation types and around one in six volunteered for three or more organisation types. This suggests that when adolescents volunteer, many are involved in a range of volunteering activities.

Figure 11.1: Volunteering at age 12-13 and 16-17, by organisation type

Notes: 95% confidence intervals are shown by the 'I' bars at the top of each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the differences in values are statistically significant. The 'Other' category includes the following types of organisations: emergency services, health or health care, teaching or training, immigrant or refugee assistance, international aid or development, law, justice, political or human rights, business or professional associations or unions, and ethnic and ethnic-Australian societies, which all had very small (less than 1% in either cohort) numbers of adolescent volunteers. n = 3,222 for B cohort (age 12-13) and 2,950 for K cohort (age 16-17).

Source: LSAC Wave 7, B and K cohorts, weighted

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

11.2 Time spent volunteering

The LSAC data show that for 12-13 year olds and 16-17 year olds, there were two common patterns of volunteering - regular commitments (weekly or fortnightly) and involvement in less frequent occasions, which might range from a one-off activity on a single day to contributions that continue for a period of time and then discontinue (Figure 11.3). There was no difference in the frequency of volunteering by gender. Given volunteering at least once a week was a very common pattern for adolescents (35% of 12-13 year olds and 38% of 16-17 year olds), it is clear that there is a large number of adolescents giving a substantial amount of time to volunteer activities.

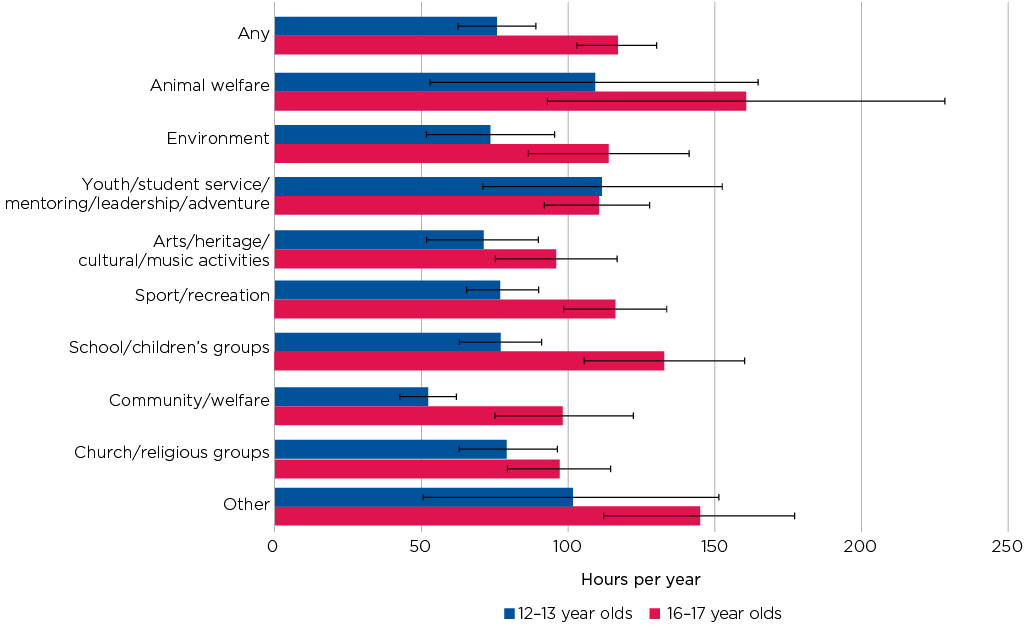

On average, 12-13 year olds who volunteered accrued 76 hours per year and 16-17 year olds engaged in 117 hours of volunteering per year. The contribution of the older cohort is similar to that reported by the ABS, which found that volunteers aged 15 years and older contributed an average of 128 hours of voluntary work in the last 12 months (ABS, 2015b). This would be influenced by the level of support provided by organisations for adolescents to participate in volunteering activities - as young people become older they become more independent and need less supervision, allowing them to volunteer for longer periods of time. This would also be supported by school requirements, which would encourage their engagement in volunteering activities. There was no significant difference in the average hours of volunteering by gender.

For 12-13 year olds, there was a difference in the number of hours that adolescents spent volunteering according to the organisation that they volunteered for (Figure 11.4).

For example, 12-13 year olds who volunteered for community or welfare organisations spent an average of 53 hours per year.2 This was the lowest of all organisation types and contrasts with those who volunteered for activities related to youth, student service, mentoring, leadership or adventure who volunteered double the amount of time (an average of 112 hours total volunteering per year). Among adolescents aged 16-17 years, there was no difference in the number of hours that young people volunteered for according to organisation type.

The average number of hours spent volunteering per week was related to the frequency of volunteering. Adolescents of both age groups who volunteered fortnightly volunteered for an average of almost two hours per week (or four hours per fortnight). This increased to an average of nearly three hours per week for those 12-13 year olds volunteering at least once a week (over four hours per week for 16-17 year olds). The LSAC data showed that adolescents at 12-13 years who volunteered less than monthly (at least once a year) did so for an average of six hours per year, or approximately three quarters of a working day. For 16-17 year olds this increased to 17 hours, or approximately two working days, over the course of a year.

Figure 11.2: Approximately 50% of 16-17 year olds had volunteered in the last 12 months

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Figure 11.3: Frequency of volunteering among volunteers at ages 12-13 and 16-17

Notes: 95% confidence intervals are shown by the 'I' bars at the top of each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the differences in values are statistically significant. B cohort: n = 1,416 volunteers only; K cohort: n = 1,649 volunteers only.

Source: LSAC Wave 7, B and K cohorts, weighted

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Figure 11.4: Average time spent volunteering in the past year for 12-13 and 16-17 year olds, by organisation type

Notes: 95% confidence intervals are shown by the 'I' bars at the top of each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the differences in values are statistically significant. 12-13 year olds: n = 1,416 volunteers only; 16-17 year olds: n = 1,649 volunteers only. The 'other' category includes the following types of organisations: emergency services, health or health care, teaching or training, immigrant or refugee assistance, international aid or development, law, justice, political or human rights, business or professional associations or unions, and ethnic and ethnic-Australian societies. The hours per year is for all voluntary work undertaken. This may have been for one or multiple organisations. Those volunteering for more than one organisation type are represented in each organisation category they volunteered for.

Source: LSAC Wave 7, B and K cohorts, weighted

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

11.3 Parents' participation in volunteering activities

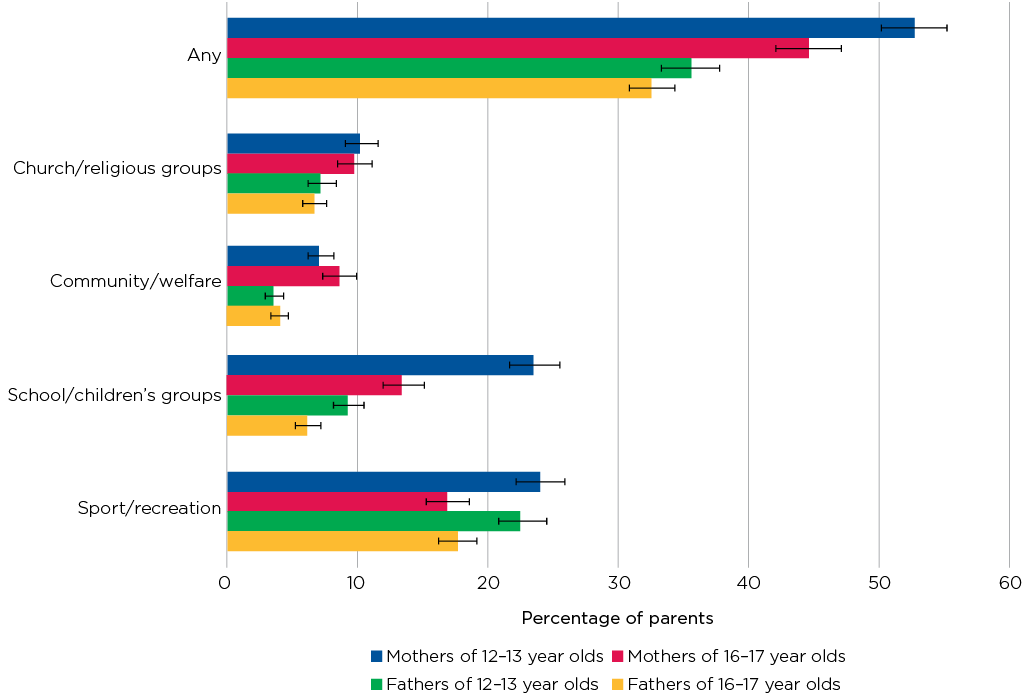

Two thirds of volunteers report having at least one parent who participated in volunteer work (ABS, 2015b). This is not surprising as parents are role models for their children's values and social behaviours. The LSAC data show that around a half of mothers (53%) and a third of fathers (36%) of 12-13 year olds had volunteered in the past year (Figure 11.5). Similar numbers of fathers of 12-13 year olds and 16-17 year olds volunteered; however, fewer mothers of 16-17 year olds than 12-13 year olds volunteered (45% vs 53%) possibly reflecting changes in mothers' lives such as increased participation in the paid workforce and less volunteering at their child's school as their children grow older.

More parents of 12-13 year olds (24% of mothers and 23% of fathers) than 16-17 year olds (17% of mothers and 18% of fathers) volunteered for sport and recreation activities (Figure 11.5), possibly due to lesser involvement and supervision in their children's sporting activities when their children are older. Similarly, involvement in school and children's groups was lower among parents of older adolescents. However, similar numbers of mothers and fathers of older and younger adolescents volunteered for church or religious groups and community or welfare organisations, suggesting that involvement in these types of volunteering is unrelated to the age of their child and more to do with family values and religious beliefs. Fathers were most likely to volunteer for sport and recreation organisations. Mothers most commonly volunteered for sport and recreation organisations and school and children's groups. Although similar numbers of mothers and fathers volunteered for sport and recreation organisations, more mothers than fathers volunteered for church or religious groups, community or welfare organisations, and school and children's groups.

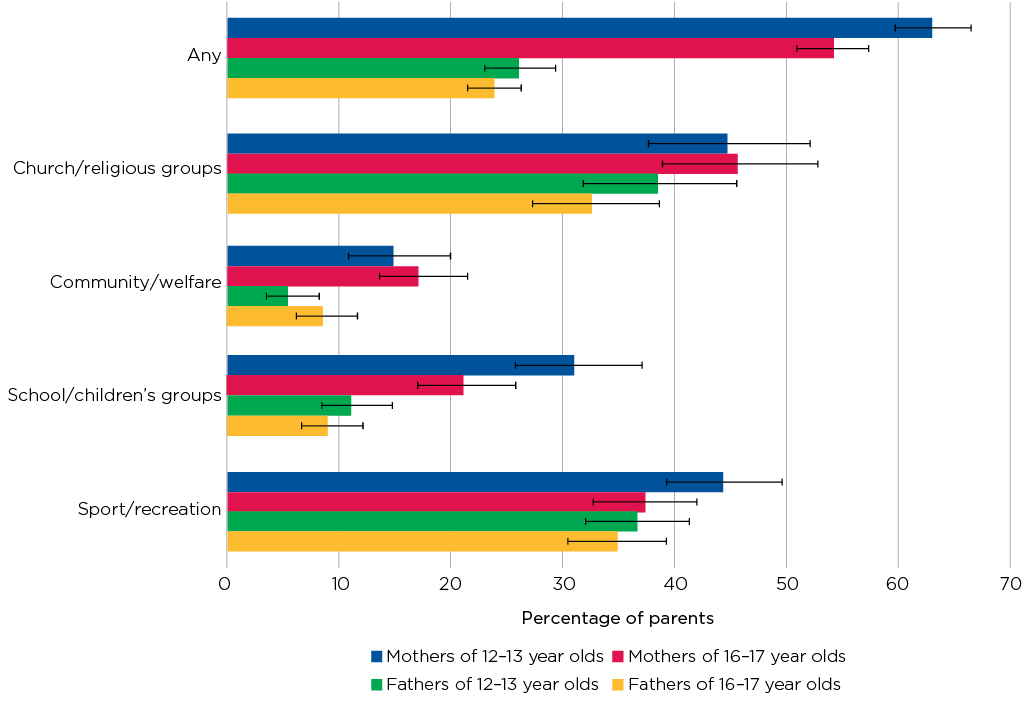

The LSAC data show that adolescents were more likely to volunteer if their parents volunteered, particularly their mother. Among volunteers, 63% of 12-13 year olds and 54% of 16-17 year olds had a mother who volunteered (Figure 11.6). Fewer adolescent volunteers had a father who volunteered (26% of 12-13 year olds and 24% of 16-17 year olds). Adolescents whose parents volunteered for sport and recreation organisations or church or religious groups were more likely to be volunteers compared to adolescents whose parents volunteered for school and children's groups or community or welfare organisations. Presumably, this is because community service is a key aspect of most religions and sport and recreation may reflect a broader family involvement with a particular sporting interest that increases the likelihood of children also becoming involved.

Figure 11.5: Mothers and fathers of 12-13 year olds and 16-17 year olds volunteering

Notes: 95% confidence intervals are shown by the 'I' bars at the top of each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the differences in values are statistically significant. n = 3,237 for B cohort mothers (age 12-13), n = 2,905 for K cohort mothers (age 16-17), n =3,319 for B cohort fathers (age 12-13) and n = 3,034 for K cohort fathers (age 16-17). Church or religious groups, community or welfare organisations, school and children's groups and sport and recreation organisations are the most common types of organisations parents volunteered for. Other categories are not shown.

Source: LSAC Wave 7, B and K cohorts, weighted

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Figure 11.6: Volunteers aged 12-13 and 16-17 years (any) who had a parent volunteering, by type of organisation parents volunteer for

Notes: 95% confidence intervals are shown by the 'I' bars at the top of each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the differences in values are statistically significant. n = 3,144 for B cohort mothers (age 12-13), n = 2,788 for K cohort mothers (age 16-17), n =3,216 for B cohort fathers (age 12-13) and n = 2,908 for K cohort fathers (age 16-17).

Source: LSAC Wave 7, B and K cohorts, weighted

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

11.4 Characteristics associated with adolescent volunteering

Adolescents' involvement in volunteering varied according to their age, and to a lesser extent, their gender. After accounting for other personal and family characteristics, these characteristics continued to be significantly associated with adolescents' volunteering behaviour (Table 11.1):

- Young people aged 16-17 had almost double the odds of being involved in some form of volunteering compared to 12-13 year olds (odds ratio = 1.8). They also had higher odds of engaging in many types of volunteering (odds ratios ranging from 1.3 to 1.8), with the largest difference relating to voluntary activities in the youth, student service, mentoring, leadership or adventure areas (odds ratio = 1.8).

- Girls had higher odds of being volunteers than boys (odds ratio = 1.3). These findings are consistent with other Australian data showing higher rates of volunteering among females than males (PricewaterhouseCoopers Australia, 2016). Gender differences were most apparent for animal welfare organisations (girls had more than double the odds of volunteering with these groups; odds ratio = 2.1).

Notes: Logistic regression models, odds ratios reported. * p < .05, ** p <.01, *** p <.001. n = 5,845. All models control for neighbourhood disadvantage (SEIFA), along with all of the other characteristics in the table. a In Wave 7 of both cohorts, the primary caregiver was asked whether the child has a condition which has lasted or is expected to last for at least 12 months, which causes him or her to use medicine prescribed by a doctor, other than vitamins, or more medical care, mental health or educational services.

Source: LSAC Wave 7, pooled data from B and K cohorts, unweighted

Birth order was also significantly related to volunteering. Compared to first-born children, adolescents who were a middle child, a twin or an only child had lower odds of engaging in voluntary work of any type (about 20-30 percentage points lower). Additionally, middle children and twins had lower odds of volunteering in youth, student service, mentoring, leadership or adventure roles, and adolescents who were the youngest or only child in the family had lower odds of volunteering for sport and recreation groups. Although it may be expected that younger siblings will follow the example set by older siblings, this idea was not supported by the data. This finding could be explained by the observation that first-born children tend to be 'highly organised achievers' (Grose, 2003), and may therefore want to participate in extracurricular activities such as volunteering. It is also possible that second-born or subsequent children may not have the same levels of access to parents' time and resources as first-born children.

As noted earlier (section 11.3), adolescents were more likely to volunteer if their parents were volunteers and, particularly so, if their mother was a volunteer. This association remained after controlling for a range of other factors. Compared to adolescents whose mothers did not volunteer, those who had a mother who did, had double the odds of volunteering themselves, and had higher odds of engaging in all types of volunteering. Adolescents also had a higher likelihood of volunteering if their father was a volunteer (odds 1.4 times higher). However, father's volunteering was only associated with increased odds of adolescents engaging in particular forms of voluntary work (i.e. church or religious groups; sport and recreation groups; and activities related to youth, student service, mentoring, leadership or adventure).

These results are consistent with other research (Van Goethem, van Hoof, van Aken, Orobio de Castro, & Raaijmakers, 2014), demonstrating that parents might act as volunteering role models for their children. The findings also demonstrate a family commitment to particular organisations, which could also assist in strengthening parent-child relationships. In addition, adolescents who had a parent with a degree had higher odds (1.3 times higher) of becoming a volunteer than adolescents whose parents had no post-secondary qualifications. More specifically, they had higher odds of volunteering for community or welfare organisations (1.8 times higher) and activities related to youth, student service, mentoring, leadership or adventure (double the odds). Adolescents whose parents had completed a post-secondary certificate or diploma also had increased odds of participating in these forms of volunteering, although the likelihood of them doing so was lower than for those with a degree.

Language spoken at home was also associated with adolescents' volunteering, which may be associated with cultural backgrounds. Compared to adolescents who only spoke English at home, adolescents who spoke a language other than English had higher odds of volunteering overall (1.3 times higher) and volunteering for:

- community or welfare organisations (1.5 times higher)

- church or religious groups (1.8 times higher)

- activities related to arts, heritage, culture or music (1.8 times higher).

The type of school an adolescent attended was related to their involvement in volunteering, with adolescents who attended Catholic or independent schools having higher odds of engaging in voluntary work than adolescents from government schools. Independent or Catholic schools may provide more opportunities and encouragement for volunteering than government schools or even mandate volunteering in some cases. The largest sector differences were found for volunteering for church or religious groups. Compared to adolescents in government schools, the odds of volunteering for church or religious groups were 2.1 times higher for adolescents in Catholic schools, and 2.3 times higher for adolescents in independent schools.3

A number of personal and family characteristics were significantly associated with specific forms of volunteering, once other factors were controlled for:

- Indigenous status was uniquely associated with voluntary activities related to arts, heritage, culture or music. This strong association may reflect the fundamental importance of art and music in the culture of Indigenous people in Australia (Department of Health, 2017). Compared to non-Indigenous adolescents, the odds of volunteering for activities related to arts, heritage, culture or music were more than tripled for adolescents with an Indigenous background.

- Adolescents with special health care needs had lower odds of volunteering for sport and recreation groups (27 percentage points lower) than those without special health care needs, suggesting that their health care needs might limit their capacity to volunteer in activities of this type.

- Income was also related to specific forms of volunteering, but not volunteering overall. Adolescents from high-income families (top third) had higher odds of volunteering for sporting and recreation groups (about 30 percentage points higher), and lower odds of volunteering for church or religious groups (45 percentage points lower) than adolescents from low-income families (bottom third). This may be associated with the cost of participating in particular activities; for example, sports uniforms.

- Region of residence was also only associated with particular types of volunteering. Compared to adolescents living in major cities, adolescents living in inner regional areas, or outer regional and remote areas had higher odds of volunteering for sport and recreation groups (1.4 and 1.5 times higher, respectively). This finding is consistent with the observation that sport and recreation activities form a major part of the culture in country areas of Australia, and these activities often rely heavily on volunteers (Tonts, 2005). Conversely, adolescents living in inner regional areas had lower odds of doing voluntary work for church or religious groups.

Summary

This chapter has provided a picture of adolescent volunteering at ages 12-13 and 16-17 in 2016. It described the types of voluntary activities that adolescents participate in and associations with individual and family characteristics, including their parents' volunteering. This adds a unique understanding of youth volunteering by providing information on young people under the age of 15.

By age 12-13 years, a considerable percentage (over 40%) of adolescents were involved in some form of volunteering and, by age 16-17, over half of young Australians reported volunteering. Adolescents most commonly volunteered for sport and recreation organisations, school and children's groups, and community or welfare organisations. At both ages, more adolescents volunteered if a parent volunteered, particularly their mother, suggesting that parents act as important role models for their children. Generally, adolescents were more likely to volunteer if they were female, older (16-17 rather than 12-13 years of age), attended independent or Catholic schools rather than government schools and had parents with higher levels of education.

These findings are encouraging because they indicate that younger Australians are engaging in voluntary activities, which may have a positive effect on their individual development and wellbeing, while also contributing to their community and Australian society more broadly. The double benefit of this engagement - in terms of benefits to society from adolescents' contributions and the benefits to the adolescents themselves in developing skills and experience beyond what they could gain in the classroom - means that efforts should be made to encourage and empower adolescents to get involved in volunteering. Given the association between volunteering by adolescents and their parents, possible approaches to increase youth volunteering would be to encourage parent volunteering and family volunteering opportunities. Future research in this area to understand the motivations of adolescents who volunteer (and who do not volunteer) would help to target efforts to encourage volunteering. Further follow-up of the volunteering behaviours of the LSAC cohorts will reveal the immediate and longer-term benefits of youth volunteering.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2011). General social survey: User guide, Australia, 2010. Paper questionnaire (cat. No. 4159.0.55.002). Canberra: ABS. Retrieved from www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/47A8702AD871F040CA2579...$File/general%20social%20survey%20questionnaire%202010.pdf

ABS. (2015a). 4159.0 - general social survey: Summary results, Australia, 2014. Canberra: ABS. Retrieved from www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/latestProducts/4159.0Media%20Release102014

ABS. (2015b). 4159.0 - general social survey: Summary results, Australia, 2014. Canberra: ABS. Retrieved from www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/4159.0Main%20Features152014?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=4159.0&issue=2014&num=&view=

ABS. (2015c). 5256.0 - Australian national accounts: Non-profit institutions satellite account, 2012-13. Canberra: ABS. Retrieved from www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/5256.0

ABS. (2018). 4159.0.55.005 - information paper: Collection of volunteering data in the ABS, March 2018. Canberra: ABS. Retrieved from www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/7d12b0f6763c78caca257061001cc588/b23e1cea513878b7ca258255000dd750!OpenDocument

Benson, P. L., Scales, P. C., & Syvertsen, A. K. (2011). The contribution of the developmental assets framework to positive youth development theory and practice. In J. V. Lerner, & J. B. Benson (Eds.), Advances in child development and behavior (pp.195 -228). London, England: Elsevier.

Catalano, R. F., Hawkins, J. D., Berglund, M. L., Pollard, J. A., & Arthur, M. W. (2002). Prevention science and positive youth development: Competitive or cooperative frameworks? Amsterdam: Elsevier Science B.V.

Charities Aid Foundation. (2018). CAF world giving index 201: A global view of giving trends. Kings Hill, United Kingdom: Charities Aid Foundation.

Department of Health. (2017). My life my lead: Opportunities for strengthening approaches to the social determinants and cultural determinants of indigenous health. Report on the national consultations. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, Department of Health.

Elder, G. H., Jr., & Conger, R. (2000). Children of the land: Adversity and success in rural America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Grose, M. (2003). Why first borns rule the world and last borns want to change it. North Sydney, Australia: Random House Australia.

Hinson, L., Kapungu, C., Jessee, C., Skinner, M., Bardini, M., & Evans-Whipp, T. (2016). Measuring positive youth development toolkit: A guide for implementers of youth programs. Washington, DC: YouthPower Learning, Making Cents International.

Lerner, R. M., Almerigi, J. B., Theokas, C., & Lerner, J. V. (2005a). Positive youth development a view of the issues. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 25(1), 10-16.

Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., Almerigi, J. B., Theokas, C., Phelps, E., Gestsdottir, S. et al. (2005b). Positive youth development, participation in community youth development programs, and community contributions of fifth-grade adolescents: Findings from the first wave of the 4-h study of positive youth development. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 25(1), 17-71.

Moorfoot, N., Leung, R. K., Toumbourou, J. W., & Catalano, R. F. (2015). The longitudinal effects of adolescent volunteering on secondary school completion and adult volunteering. International Journal of Developmental Sciences, 9(3-4), 115-123.

Moreno, M. A., Furtner, F., & Rivara, F. P. (2013). Advice for patients. Adolescent volunteering. JAMA Pediatrics, 167(4), 400.

PricewaterhouseCoopers Australia. (2016). State of volunteering in Australia. Australia: PricewaterhouseCoopers Australia.

Ranapurwala, S. I., Casteel, C., & Peek-Asa, C. (2016). Volunteering in adolescence and young adulthood crime involvement: A longitudinal analysis from the add health study. Injury Epidemiology, 3(1), 26-35.

Schreier, H. M., Schonert-Reichl, K. A., & Chen, E. (2013). Effect of volunteering on risk factors for cardiovascular disease in adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA Pediatrics, 167(4), 327-332.

Tonts, M. (2005). Competitive sport and social capital in rural Australia. Journal of Rural Studies, 21(2), 137-149.

Van Goethem, A. A. J., van Hoof, A., van Aken, M. A. G., Orobio de Castro, B., & Raaijmakers, Q. A. W. (2014). Socialising adolescent volunteering: How important are parents and friends? Age dependent effects of parents and friends on adolescents' volunteering behaviours. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 35(2), 94-101.

Volunteering Australia. (2015). Key facts and statistics about volunteering in Australia. Canberra: Volunteering Australia.

Walsh, L., & Black, R. (2015). Youth volunteering in Australia: An evidence review. Canberra: Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth.

1 This does not necessarily mean that adolescents only volunteered for one organisation; they may have volunteered for multiple organisations of the same type.

2 The number of hours is the total time spent volunteering for all organisation types. LSAC participants were not asked separately about the time spent volunteering for each organisation type. Individuals who volunteered for more than one type of organisation are represented in each category they volunteered for.

3 Separate analyses were conducted for the K cohort alone, where adolescents aged 16-17 years were additionally asked whether they are active in a religious or spiritual group, such as regularly going to services, Sunday school or a religious youth club. After adjusting for all other variables, compared to adolescents who were not, adolescents who were active in a religious or spiritual group had 1.6 times the odds of any volunteering; 1.9 times the odds of volunteering related to youth, student service, mentoring, leadership or adventure; 1.7 times the odds of volunteering related to arts, heritage, cultural or music activities; 1.3 times the odds of volunteering for community or welfare organisations; 9.9 times the odds of volunteering for church or religious groups; and lower odds of volunteering for sport and recreation organisations (reduced by 31 percentage points).

Acknowledgements

Featured image: © GettyImages/imgorthand