Intimate partner violence among Australian 18–19 year olds

Intimate partner violence among Australian 18–19 year olds

Snapshot Series – Issue 11

Some of the following content may be distressing for the reader. If you need support, please call 1800RESPECT (1800 737 732), and for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 13YARN (13 92 76), or see our list of local support services.

Intimate partner violence is never the victim's fault

This snapshot examines risk and protective factors for intimate partner violence victimisation among Australian adolescents. This helps policy makers and service providers to identify populations that could be at increased risk, so that protective factors can be strengthened. Although the current snapshot focuses on victim-survivors, we emphasise that prevention of intimate partner violence perpetration should be a core focus of policy intervention.

What do we know?

During the teenage years, intimate partner relationships become increasingly important. When navigating these partnerships for the first time, young people are exposed to many new experiences. For some, these ‘new experiences’ can include intimate partner violence as either perpetrators or victims of physical, emotional or sexual violence and abuse (Crooks, Jaffe, Dunlop, Kerry, & Exner-Cortens, 2019). The adolescent and young adult life periods have the highest rates of intimate partner violence across the life span (Johnson, Giordano, Manning, & Longmore, 2015).

Intimate partner violence is a significant violation of the rights and safety of young people and without early intervention, can have lifelong impacts for victim-survivors and perpetrators (Exner-Cortens, 2014). Much of the research to date has focused on identifying risk factors that increase the likelihood of perpetration and/or victimisation among young people; for example, exposure to partner violence in one’s family of origin (Capaldi, Low, Tiberio, & Shortt, 2019; Kaufman-Parks, DeMaris, Giordano, Manning, & Longmore, 2018; Louis & Reyes, 2023). Recently, greater attention has been given to protective factors that reduce the likelihood of intimate partner violence, such as supportive relationships with peers and parents (Hébert et al., 2019).

Peers and parents can serve as key sources of informal support in the context of intimate partner violence victimisation (Greenman & Matsuda, 2016). They can provide emotional support, assist with safety planning, offer information, resources or advocacy and encourage seeking formal help from purpose built organisations (Sylaska & Edwards, 2014). The support of peers and parents is crucial to empowering victim-survivors to seek help and take steps towards safety and healing. Therefore, when addressing the issues of intimate partner violence and abuse among Australian adolescents, it is crucial that we further understand the potentially protective role of peers and parents.

What can we learn?

This snapshot focuses on victim-survivors of intimate partner violence. As such, the core aim of this work is to further understand the scope of intimate partner violence victimisation among Australian 18–19 year olds. Specific focus is given to different forms of intimate partner violence victimisation, and rates of intimate partner violence among adolescent females and males. The potentially protective role of peers and parents against intimate partner violence is considered. The following questions are addressed: (1) How prevalent is intimate partner violence and abuse victimisation among adolescents aged 18–19 years? (2) What are the most common violent or abusive behaviours experienced by adolescents in an intimate relationship? (3) Do supportive friendships in the teen years reduce the risk of intimate partner violence and abuse victimisation at ages 18–19 years? (4) Do supportive relationships with parents in the teen years reduce the risk of intimate partner violence and abuse victimisation at ages 18–19 years?

Terminology

Intimate partner violence: Across research and policy, in both Australia and elsewhere, intimate partner violence can also be referred to as ‘domestic violence’, ‘domestic and family violence’, ‘domestic abuse’, ‘domestic violence and abuse’, and ‘dating violence’. The terms ‘adolescent dating violence’ and ‘teen dating violence’ are also common when describing intimate partner violence among young people.1 In this snapshot, the term intimate partner violence is used throughout.

Victim-survivor:In this snapshot, young people who have experienced intimate partner violence victimisation will be referred to as victim-survivors. This is the most widely used term to describe someone who has experienced intimate partner violence, family and domestic violence or gender-based violence victimisation, and acknowledges their strength and resilience.2

In focus

This snapshot uses data from the LSAC K cohort at Wave 8, which were collected in 2018. There were 3,037 K cohort participants aged 18–19 years who completed the Wave 8 survey (61% of the original eligible Wave 1/2004 sample and 98% of the Wave 7/2016 sample).

Fifty-nine per cent (n = 1,788) of LSAC K cohort respondents indicated having been in a romantic relationship since age 16 (i.e. had reported ‘going out’ with someone at ages 16–17 or 18–19). This group were asked a series of questions relating to intimate partner violence and abuse in the 12 months prior to their interview. These questions were then categorised as either emotional abuse (8 items), physical violence (5 items) or sexual abuse (2 items).

Experiences of intimate partner violence among 18–19 year olds

Intimate partner violence can take many forms, in the current snapshot, the rates of emotional abuse, physical violence and sexual abuse are considered. Emotional abuse, also known as psychological abuse, is characterised by a pattern of actions or behaviours that are intended to manipulate, control, isolate or intimidate another person.3 Physical violence includes the use of physical force with the intent to cause injury or harm. Sexual abuse involves sexual acts that are committed or attempted without the explicit informed consent of the other person and/or despite their refusal (Breiding, Basile, Smith, Black, & Mahendra, 2015).

In the LSAC data, 29% of 18-19 year olds reported some form of intimate partner violence. Emotional abuse was the most common form of intimate partner violence reported – experienced by 25% of young Australian women and men. Physical violence was experienced by 12% of adolescents and sexual abuse was experienced by 8% of adolescents.4

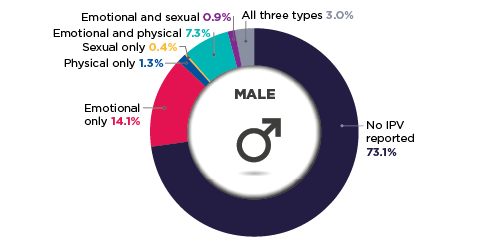

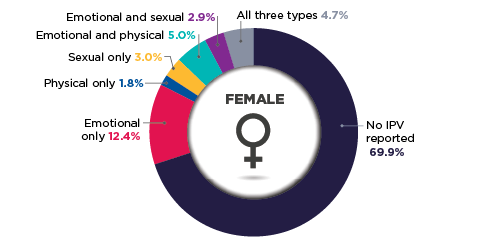

Figure 1: Three in 10 young women and men aged 18–19 years reported at least one experience of intimate partner violence in the previous year5

Prevalence rates of forms of intimate partner violence among by 18–19 year old Australians

Young women more likely to experience sexual abuse than young men6

Young women were more likely to be victim-survivors of sexual abuse than young men – with 11% of females aged 18–19 years reporting sexual abuse, compared to 4% of males of the same age. The rates of victimisation of emotional abuse and/or physical violence did not differ substantially between young women and young men, with 25% of women and men reporting emotional abuse, and 12% of women and men reporting physical abuse.

Many victim-survivors experienced two or three types of intimate partner violence

Overall, 17% of adolescents reported experiencing one type of intimate partner violence or abuse, 8% reported experiencing two types of intimate partner violence or abuse and 4% reported experiencing three types of intimate partner violence or abuse. Emotional abuse and physical violence were the most likely to co-occur, reported by 7% of young male victim-survivors and 5% of female victim-survivors (Figures 2 and 3). These values are consistent with international estimates (Hacıaliefendioğlu, Yılmaz, Koyutürk, & Karakurt, 2020).

Around 5% of young female victim-survivors reported the co-occurrence of all three types of intimate partner violence. An estimated 3% of young male victim-survivors reported all three types of violence and abuse. Emotional and sexual abuse were the least likely to co-occur, reported by 1% of young male victim-survivors and 3% of young female victim-survivors.

Figure 2: Distribution of types of violence among the 27% of males aged 18–19 years reporting any violence or abuse

Notes: Weighted distribution among male adolescents who are victim-survivors of intimate partner violence. The proportion of adolescents that reported a combination of physical violence and sexual abuse was negligible and therefore not included.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Wave 8, weighted. N = 875, population estimate = 73,469.

Figure 3: Distribution of types of violence among the 30% of females aged 18–19 years reporting any violence or abuse

Notes: Weighted distribution among female adolescents who are victim-survivors of intimate partner violence. The proportion of adolescents that reported a combination of physical violence and sexual abuse was negligible and therefore not included.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Wave 8, weighted. N = 913, population estimate = 74,733.

Emotional abuse was the most prevalent form of abuse experienced by victim-survivors

Considering the rates of specific abusive or violent behaviours experienced by victim-survivors provides a more detailed understanding of intimate partner violence among Australian adolescents.7

Forms of emotional abuse were the most prevalent type of intimate partner violence reported. Just over 16% of victim‑survivors of emotional abuse reported that an intimate partner has said that they are ‘crazy, stupid or not good enough. Around 12% of victim‑survivors of emotional abuse were blamed by their perpetrator – being told that they ‘caused’ the violent behaviours. Twelve percent of victim-survivors of emotional abuse experienced technology facilitated harassment such as over the phone, by text message, email or social media. The least prevalent form of emotional abuse was ‘being kept from their job, money or financial resources’, with these financial forms of emotional abuse reported by 2% of victim-survivors.

The most common form of physical violence, reported by approximately 10% of physical violence victim‑survivors, was being shaken, pushed, grabbed or thrown by their intimate partner. This form of physical violence was almost twice as common as being hit with a fist or object, kicked or bitten (or attempts at such behaviours). Other forms of physical violence, such as being choked, harmed (or threatened) by a knife, gun or other weapon, or/and confinement in a locked room were least common, experienced by 2%–3% of physical violence victim‑survivors.

Forms of sexual abuse were higher among female victim-survivors than their male counterparts. Compared to 3% of male victim‑survivors, 9% of female victim‑survivors of sexual abuse reported that they were made to perform sex acts they did not want to perform. Furthermore, around 7% of female sexual abuse victim‑survivors reported that they were forced into having sex with their intimate partner, compared to 3% of male sexual abuse victim‑survivors.

Intimate partner violence protective factors

Supportive friendships throughout adolescence play a protective role

Peer relationships are extremely important during adolescence. Friends provide young people with the opportunity for connection, belonging and exploration of the self that is differentiated from their family. Close friendships are a key source of social support for adolescents and are especially advantageous to wellbeing when they provide a trusting space for young people to talk through their thoughts, feelings and difficulties.

In the current findings, supportive friendships during adolescence reduced the risk of later emotional abuse victimisation by 36% (Figure 4). This is consistent with established and emerging evidence that high-quality adolescent friendships lower the likelihood of intimate partner violence in adulthood (Alvarez-Lizotte et al., 2020; Linder & Collins, 2005).

Figure 4: Supportive friendships lower the risk of emotional abuse victimisation

Results from generalised structural equation model estimating the relationship between supportive friendships and intimate partner violence at age 18–19 years

Notes: Full results are available in Table S2 of the supplementary materials. Covariates include relationship quality with parents, bullying, gender, gender role attitudes, parental education, exposure to inter-parental hostility during childhood, parent experiences of childhood abuse and violence, financial hardship and area disadvantage. N = 1,489.

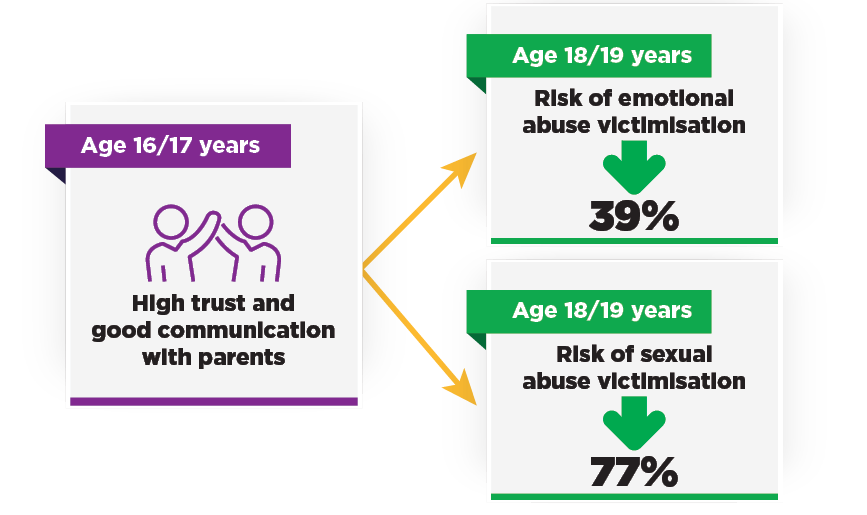

Trust and good communication with parents throughout adolescence are protective

Although peers are of increased importance during adolescence, parents continue to provide a secure emotional base for young people to feel valued, understood, accepted and loved. Parent–child relationships that are supportive, trusting and promote good communication throughout adolescence can foster constructive conflict resolution skills for future intimate relationships (Conger, Cui, Bryant, & Elder Jr, 2000; Jamison & Lo, 2021).

Considering intimate partner violence at ages 18–19, it was found that trust and good communication with parents earlier in adolescence reduced the risk of later emotional and sexual abuse victimisation (Figure 5). Compared with low levels of trust and communication, the risk of experiencing emotional abuse decreased by 39% among adolescents with high levels of trust and communication with their parents, while the risk of sexual violence decreased by 77%.

Figure 5: Trusting and communicative relationships with parents lowers the risk of emotional and sexual abuse

Results from generalised structural equation model estimating the relationship between trusting and communicative relationships with parents and intimate partner violence at age 18–19 years

Notes: Full results are available in Table S2 of the supplementary materials. Covariates include relationship quality with parents, bullying, gender, gender role attitudes, parental education, exposure to inter-parental hostility during childhood, parent experiences of childhood abuse and violence, financial hardship and area disadvantage. N = 1,489.

Relevance for policy and practice

Intimate partner violence amongst adolescents is at concerning levels, with the findings showing that approximately three in 10 young people have experienced some type of violence or abuse. In agreement with the National Plan to End Violence Against Women and Children 2022–2032, this snapshot highlights the need for primary prevention, as well as demonstrating the importance of early intervention.

Acknowledging that Growing Up in Australia only collects data on victim-survivors, several areas relevant for families could be addressed, including:

- Increasing awareness of the prevalence of intimate partner violence among practitioners in health and community services that work with young people.

- Within these service settings, it is essential that practitioners are mindful that young men are just as likely to be victim-survivors of emotional abuse and physical violence as young women. However, young women are more likely than young men to be victim-survivors of sexual abuse within intimate partner relationships.

- This could help practitioners to appropriately identify at-risk adolescents and ensure that the right referral pathways for support services are provided.

- Supporting evidence-based respectful relationship education for children and young people that addresses gender inequality and the underpinnings of violent or abusive behaviours. In other high-income countries like Australia these programs have been effective in reducing intimate partner violence among youth.8

- Implementing family-based programs9 that focus on improving communication between parents, model respectful relationships to children and young people, as well as increase parents’ awareness of their children’s relationships with peers and partners to identify risks of abusive behaviours as victims or perpetrators.

- As a primary source of informal support, arming parents and adolescents with the appropriate resources and knowledge if their child or friend discloses experiencing violent or abusive behaviours from their intimate partner.

- A key focus here is to ensure that victim-survivors are appropriately supported when they reach out for help but, equally, that recipients of such disclosures feel capable to respond and experience less psychological distress.10

Potential of the Growing Up in Australia study

A number of research questions could be further explored with the current available data, as well as upcoming waves of data collection (B cohort aged 18–19 and K cohort aged 22–23).

Using currently available data:

- What are the protective factors that reduce the risk of intimate partner violence and abuse among adolescents in higher risk family environments (e.g. parents abused in childhood, anger/hostility in parent relationship)?

- For example, support from adults outside the household, engagement in extracurricular activities and parental help seeking.

Using future data:

- Do respondents who reported intimate partner violence and abuse at age 18–19 report violence and abuse again at age 22–23? What are the factors associated with cessation and onset of intimate partner violence and abuse in the transition to adulthood?

- What is the prevalence of intimate partner violence and abuse among 18–19 year olds in 2023? Has it changed compared to the prevalence among 18–19 year olds in 2018?

- How does the experience of intimate partner violence at 18–19 years of age impact the timing of family formation and later relationship quality during young adulthood?

Media release

Three in ten older teens have experienced intimate partner violence

News stories

- Teenagers experiencing intimate partner violence at 'troubling' rates, research finds

- Intimate partner violence happens to teens too

- Nearly 30% of late teens suffer intimate partner violence

- Aussie Teens Are Experiencing Devastatingly High Rates Of Intimate Partner Violence

- New research: One third of teens experience intimate partner violence – this is preventable

- UOW student forms domestic violence advocacy organisation

Further details

Technical details of this research, including description of measures, detailed results and bibliography are available to download as a PDF [256 kB]

About the Growing Up in Australia snapshot series

Growing Up in Australia snapshots are brief and accessible summaries of policy-relevant research findings from Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC). View other Growing Up in Australia snapshots in this series.

1 For insights on how youth aged 16–18 years define intimate partner violence and abuse see Carlisle, E., Coumarelos, C., Minter, K., & Lohmeyer, B. (2022). ‘It depends on what the definition of domestic violence is’: How young Australians conceptualise domestic violence and abuse (Research report, 09/2022). Sydney: ANROWS.

2 For more on preferred terminology see ‘Glossary’ in Department of Social Services. (2022). National plan to end violence against women and children 2022–2032. Canberra: Government of Australia. apo.org.au/node/319995

3 Domestic Violence: Experiences of Partner Emotional Abuse (abs.gov.au)

4 Full results available in Figure S1 of the supplementary materials.

5 Full results are available in Table S1 of the supplementary materials.

6 No participants in the sample indicated they were nonbinary.

7 Full results are available in Table S2 of the supplementary materials.

8 Our Watch. The evidence for respectful relationships education.

9 The Stop it at the Start campaign is an example of one such program that is currently being rolled out Respect.gov.au – Violence against women. Let’s stop it at the start

10 Bundock, K., Chan, C., & Hewitt, O. (2020). Adolescents’ help-seeking behavior and intentions following adolescent dating violence: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 21(2), 350–366.

Acknowledgements

Authors: Dr Karlee O’Donnell, Dr Pilar Rioseco, Amanda Vittiglia and Dr Lisa Mundy

Series editors: Dr Tracy Evans-Whipp, Dr Bosco Rowland and Dr Lisa Mundy

Copy editor: Katharine Day

Graphic design: Lisa Carroll

This snapshot benefited from academic contributions from from Dr Antonia Quadara, Dr Rachel Carson, Dr Jennifer Prattley, Dr Neha Swami, Dr Clement Wong, Dr Tracy Evans‑Whipp, Dr Bosco Rowland, Dr Chris Schilling and Dr Sharman Stone.

This research would not have been possible without the invaluable contributions of the Growing Up in Australia children and their families. Website: growingupinaustralia.gov.au Email: [email protected] The study is a partnership between the Department of Social Services and the Australian Institute of Family Studies, and is advised by a consortium of leading Australian academics. The Australian Bureau of Statistics were also partners of the study until 2022, with Roy Morgan joining at this point. Findings and views expressed in this publication are those of the individual authors and may not reflect those of the Australian Institute of Family Studies, the Department of Social Services, the Australian Bureau of Statistics or Roy Morgan.

Featured image: © GettyImages/janiecbros

Publication details

O’Donnell, K., Rioseco, P., Vittiglia, A., Bowland, R., & Mundy, L. (2023). Intimate partner violence among Australian 18–19 year olds. (Growing Up in Australia Snapshot Series – Issue 11). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.