Experience of sexual harassment among young Australians: Who, where and how?

Experience of sexual harassment among young Australians: Who, where and how?

Snapshot Series – Issue 12

Responsibility for sexual harassment sits with the person who engages in (perpetrates) the behaviour, not the victim-survivor who experiences it. However, there is limited data on people who engage in sexual harassment. Hence, this snapshot examines factors that are associated with a reduced or increased likelihood of young Australians experiencing sexual harassment. These findings can help policy makers and service providers identify subgroups of young people that could be at greater risk, so that protective factors can be strengthened.

What do we already know?

Sexual harassment is a significant social issue, and young females are most affected. Nationally, 13% of women and 4.5% of men aged 18 years or over experienced sexual harassment in the 12 months to the time they were surveyed in 2021–22 (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2021–22). For young women (aged 18–24 years) it was much higher at 35%.

Sexual harassment is when a person behaves in a sexual manner that is unwelcome, and it makes another person feel intimidated, uncomfortable, degraded, humiliated or offended (ABS, 2021–22). Sexual harassment can take different forms, take place in different environments and includes behaviours that are illegal, such as rape or sexual assault. It can be verbal (sexual remarks, jokes), physical (touching and grabbing) or visual (showing sexually explicit images); and direct or indirect (e.g. publishing sexually related rumours). It can take place online and offline (at school, home, the workplace) and via technology (e.g. texting) (Douglass et al., 2018).

Australian evidence on the experience of sexual harassment for adolescents and young adults is limited. There are 2 available studies but they are not nationally representative, one is longitudinal and was conducted in one state only (Lei et al., 2020) and the other is cross-sectional and recruited participants using convenience sampling, so is not representative of the general population (Douglass et al., 2018). The first of these studies reported that 41% of New South Wales (NSW) high school students from 13 schools experienced sexual harassment in the past school term (Lei et al., 2020). The second study reported that among young people aged 15–19 years, 64% experienced sexual harassment in person and 54% through technology in the past 12 months (Douglass et al., 2018). There are studies that are representative of Australian young people but those aged less than 18 years have been excluded (ABS, 2021–22; Australian Human Rights Commission [AHRC], 2017; Heywood et al., 2022).

Some groups of young people are at greater risk. A recent scoping review (Bolduc et al., 2023) found that young people experiencing higher levels of sexual harassment was significantly associated with:

- factors such as sex, gender, sexual and gender diverse identities, low socio-economic status and household structure

- family-related factors such as violence and conflict among family members

- peer-related factors such as peer delinquency and poor peer relationships.

However, all the evidence in this scoping study was international (USA, Canada and Sweden) and mostly cross-sectional (Bolduc et al., 2023).

Greater use of digital technologies can also expose young people to the harms and risks associated with that technology. A study from the USA found that the internet and social media, when widely used, can increase young people’s vulnerability to experiencing sexual harassment (Ybarra & Mitchell, 2008). More recent Australian evidence suggests that 3 in 10 young people (8–17 years) experienced online harm where someone made unwanted contact or they were sent unwanted inappropriate content such as porn or violent content (eSafety Commissioner, 2018). Moreover, LGBTIQ+ teens, young people with disability or First Nations young people are much more likely than the national average to have experienced hurtful and hateful online interactions (eSafety Commissioner, 2022, 2023, 2024).

How will this research build the evidence base?

This is the first Australian evidence from a nationally representative sample on the experience and nature of sexual harassment among young people that includes those aged less than 18 years. This study focuses on the experience of sexual harassment among young people aged 16–19 years. This study also explores factors that can reduce or increase the likelihood of experiencing sexual harassment.

Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children collected data on the experience of sexual harassment from young people aged 16–17 years in 2016 and 18–19 years in 2018. This provides a unique opportunity to address the research gaps discussed earlier. In this snapshot, we investigate the following 4 research questions:

1.What is the prevalence of sexual harassment experienced by young people?

2.What is the nature of sexual harassment experienced by young people (i.e. types, experiencing multiple forms and relationship to perpetrator)?

3.Where do young people experience sexual harassment?

4.Which factors are associated with the experience of sexual harassment among young people?

The ‘Data in focus’ section provides further details on the study measures related to the experience of sexual harassment used in this study and statistical methods used in analysing the data. Details on other measures are provided in the supplementary materials.

Data in focus

Study sample

The study sample includes participants from LSAC K cohort who responded to the sexual harassment question in Waves 7 and 8, collected in 2016 and 2018 respectively. There were 2,930 young people aged 16–17 years in 2016 (62% of the eligible sample in Wave 1 in 2004) and 2,644 young people aged 18–19 years in 2018 (61% of the eligible sample in Wave 1 in 2004) who reported their experience of sexual harassment and unwanted sexual behaviours. Full details of the study sample, measures used and full results are provided in the supplementary materials.

Sexual harassment behaviours

In 2016, young people aged 16–17 years were asked about whether they had experienced any of the following 3 sexual harassment behaviours in the last 12 months.

- Someone told, showed or sent sexual pictures, stories or jokes that made me feel uncomfortable.

- Someone made sexual gestures, rude remarks, used body language, touched or looked at me in a way that embarrassed or upset me.

- Someone kept asking me out on a date or asking me to hook up although I said ‘No’.

In 2018, young people aged 18–19 years were asked the same question with an additional 3 sexual harassment behaviours included:

- Someone requested or pressured me for sex or other sexual acts.

- Someone raped me, attempted to rape me or sexually assaulted me.

- Someone subjected me to other unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature.

The response options for each behaviour were ‘Yes’ and ‘No’.

Place

In 2016, for those who had experienced any form of sexual harassment in the past 12 months, they were asked, ‘Where did this/these happen?’ and were given 3 response options:

- At place of study

- At work

- Other.

In 2018, 2 more response options were added to the above 3 options and open-text responses were also allowed for those who responded ‘other’:

- At a party, club or bar

- Online

- Other (specify).

Young people could choose multiple options.

Relationship to the person engaging in sexual harassment

In 2018, young people who had experienced any form of sexual harassment were also asked, ‘What was your relationship to this person/those people when this happened?’ and provided with the following response options:

- Person at your place of study

- Person at work

- Person related to work (e.g. customers or business clients)

- Stranger

- Boyfriend/girlfriend/partner

- Friend

- Other.

Young people could choose multiple options.

Limitations of the sexual harassment measures

The questions on sexual harassment have some limitations including the use of:

- language such as ‘uncomfortable’, ‘embarrassed’ or ‘upset’ to suggest that the behaviour was not consensual - this language applies a lower threshold than the Sex Discrimination Act 1984, which defines sexual harassment as any unwelcome sexual behaviour that is likely to offend, humiliate or intimidate.

- the word ‘No’ to identify whether consent was given or not − the current understanding of consent suggests that the absence of a no is not sufficient to prove consent.

- the word ‘requested’ in the response option ‘Someone requested or pressured me for sex or other sexual acts’ − this is problematic because a person requesting and being respectful with being rejected isn’t sexual harassment.

- the response option on rape or sexual assault does not cover attempted sexual assault as the word ‘attempted’ isn’t specified in relation to sexual assault as it is for rape.

Analysis

We use number (n) and per cent (%) as descriptive statistics for the types of sexual harassment, experiences of multiple forms, the relationship to the perpetrator and place of the harassment. We investigated the association between different factors at ages 14–15 (family and peer) or 16–17 (family and peer) years that can increase or decrease the risk of experiencing sexual harassment at ages 16–17 or 18–19 years respectively. In addition, we also examined the association between social media use and experience of sexual harassment at age 18–19 years. To investigate the association, we used logistic regression, adjusting for covariables, and subsequently used the model to estimate marginal probabilities. All analysis was done separately by sex at birth and by gender and sexual diversity based on evidence that these characteristics also influence the risk of sexual harassment. Descriptions of the factors examined are provided in the supplementary materials. All estimates are weighted by key socio-demographic factors.

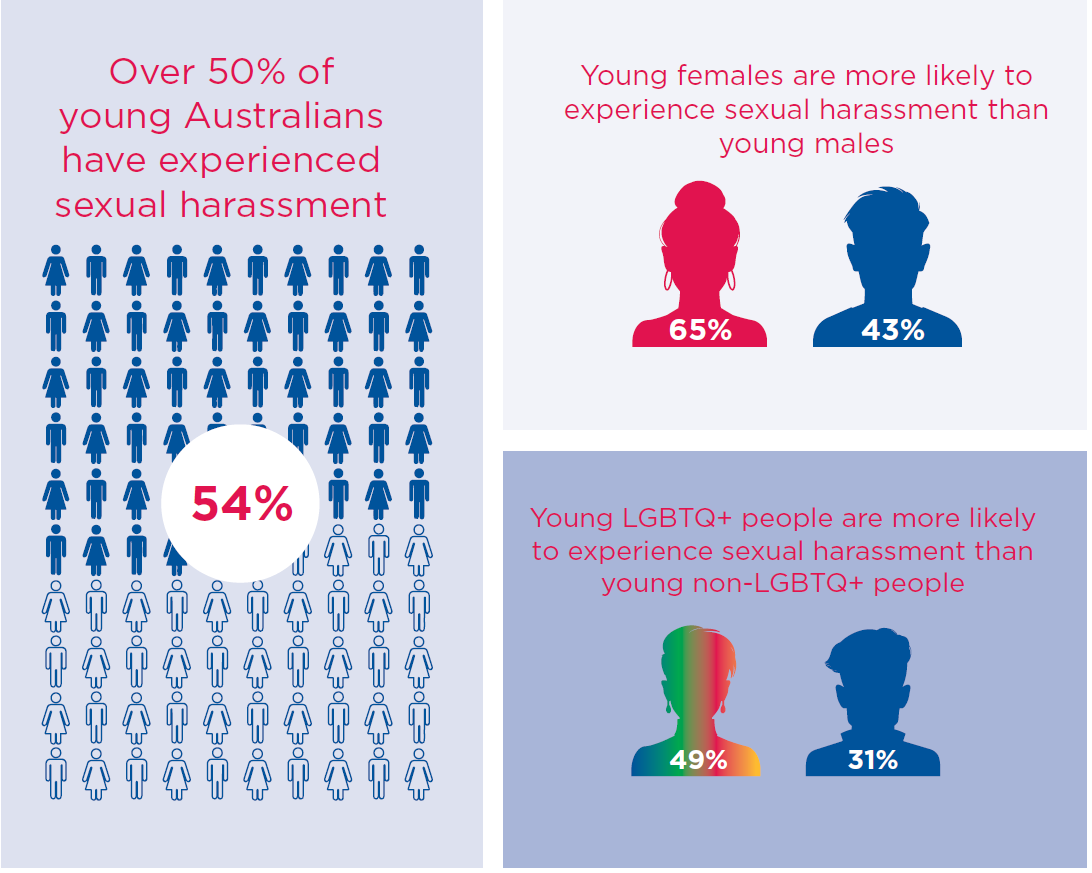

Experience of sexual harassment among young males and females

What is the prevalence of sexual harassment?

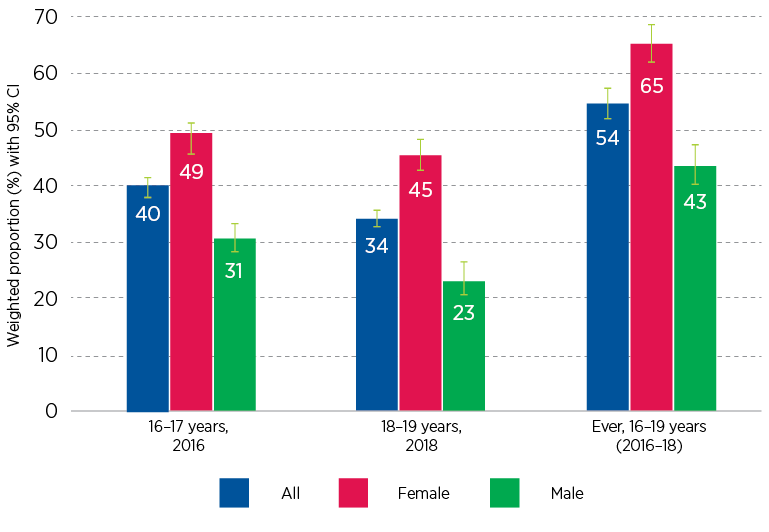

Young females were more likely to experience sexual harassment than young males. For young females aged 16–17 years in 2016, around half reported experiencing sexual harassment (of any type) in the past 12 months, compared to around one-third of young males. Slightly lower proportions were reported for these young people when they were aged 18–19 years, in 2018, (45% of young females and 23% of young males) (Figure 1).

Overall, 65% of young females and 43% of young males reported experiencing sexual harassment by 18–19 years of age (Figure 1). Among young females who reported experiencing sexual harassment, 29% experienced it both at 16–17 and 18–19 years. Among young males, 11% experienced it at both ages.

Figure 1: Prevalence of any form of sexual harassment in the last 12 months in 2016 and 2018

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 7 & 8; n(male) = 1,486 (2016) and 1,330 (2018); n(female) = 1,444 (2016) and 1,315 (2018)

The prevalence of sexual harassment showed no statistically significant difference across most personal characteristics including language background, household composition, where you lived or employment status (details on the other characteristics are provided in the supplementary materials Table S2). The exception was disability status.

Young people aged 18–19 years with any medical conditions or disability that has lasted, or is likely to last, for 6 months or more were more likely to report having experienced sexual harassment (42%) than those without (33%). There is not enough evidence to confirm the differences in prevalence of sexual harassment by disability status at age 16–17 years (supplementary materials Tables S3 and S5).1

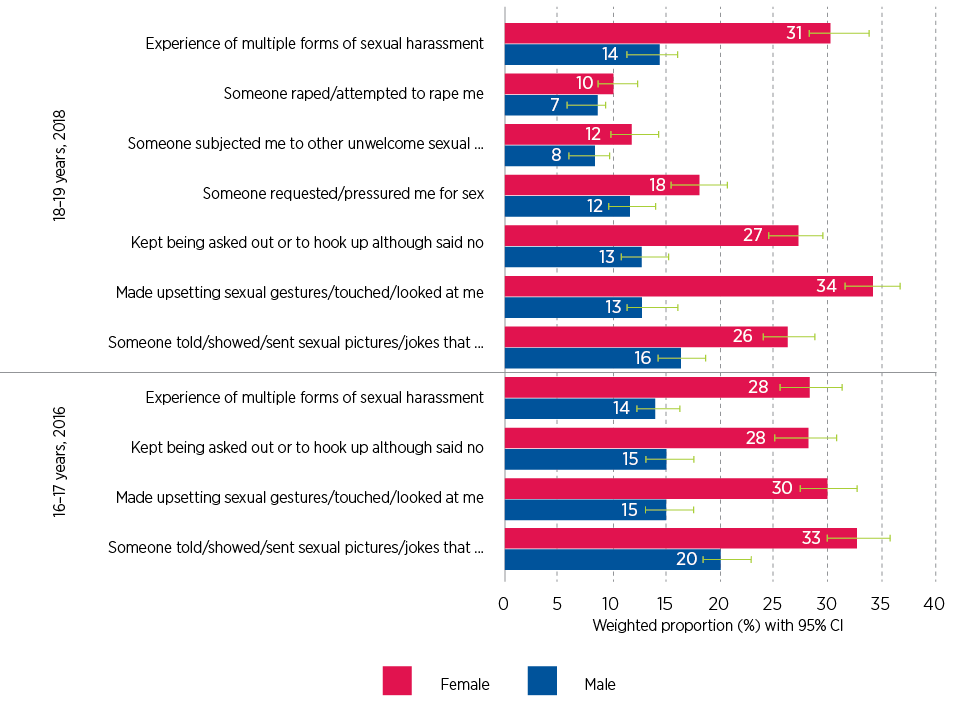

In 2016, the most common form of harassment was someone telling, showing or sending sexual pictures, stories or jokes that made the receiver uncomfortable (Figure 2). A third of females (33%) and 1 in 5 males (20%) reported this form of harassment at age 16–17 years. Making sexual gestures, rude remarks, touching or looking at the person in a way that embarrassed or upset the receiver was the next most common, reported by 30% of females and 15% of males.

Three new sexual harassment behaviours were added in 2018, meaning overall levels of sexual harassment are not comparable between 2016 and 2018. The most common form of harassment differed for young females and males aged 18–19 years. Among females, the most common form was someone who made sexual gestures, rude remarks, touching or looking at the person in a way that embarrassed or upset them (34%), followed by someone who kept asking them out or to hook up (27%) and someone who sent sexual pictures, stories and jokes (26%). Among males aged 18–19 years, the most common form was someone who sent sexual pictures, stories and jokes (16%) (Figure 2).

Young people aged 18–19 years who only reported experiencing the 3 new forms (being requested/pressured for sex; subjected to unwanted sexual conduct; or raped, attempted rape or sexually assaulted) was 2%.

In terms of experiencing multiple forms, young females were more likely to experience multiple types of sexual harassment at both ages. For young females, the proportion was 28% in 2016 and 31% in 2018, compared to 14% of young males in both 2016 and 2018 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Proportion of young people who experienced different forms of sexual harassment in the last 12 months, 2016 and 2018

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 7 and 8, weighted; n(male) = 1,486 (2016) and 1,330 (2018); n(female) = 1,444 (2016) and 1,315 (2018)

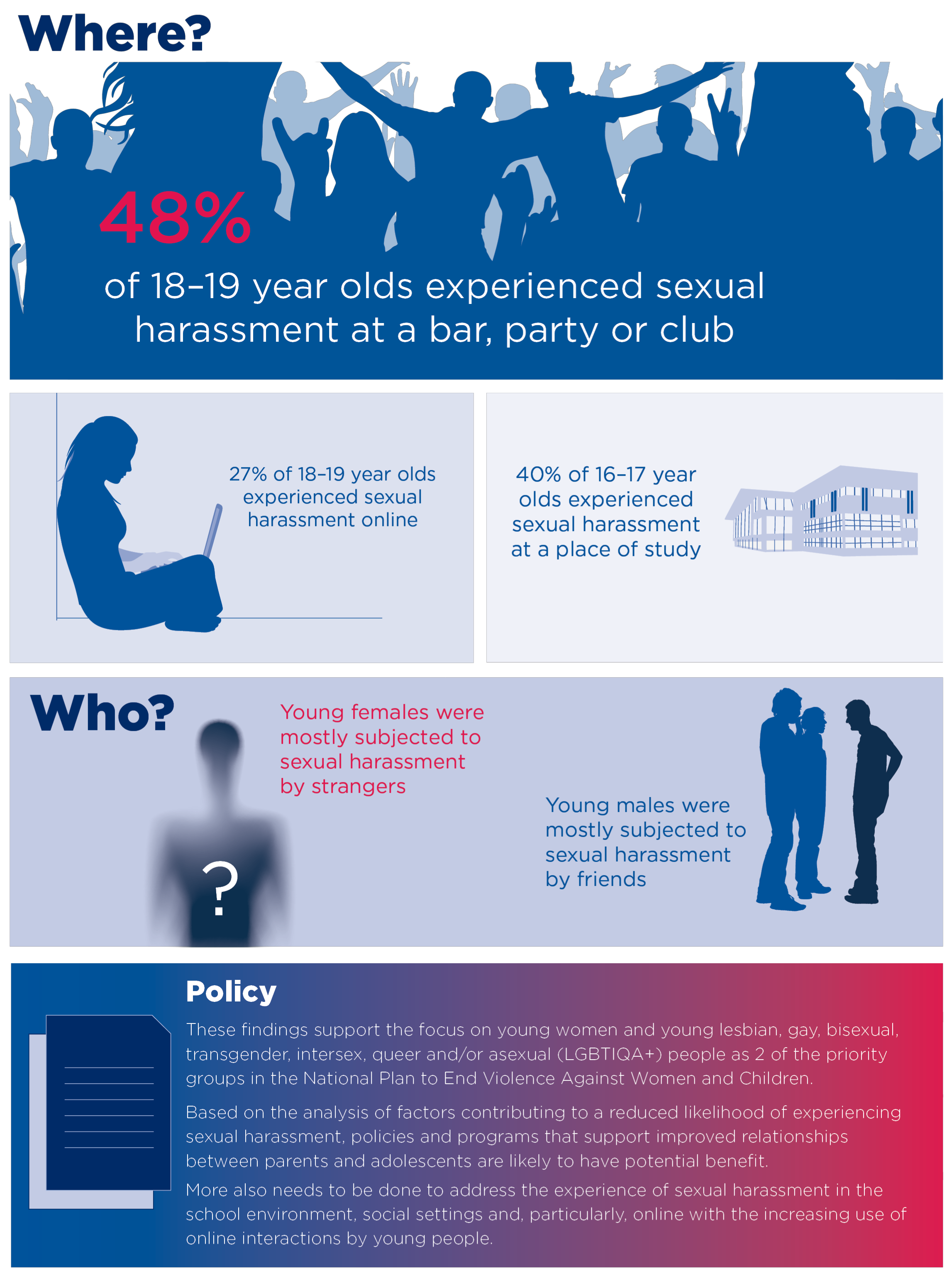

Where did young people experience sexual harassment?

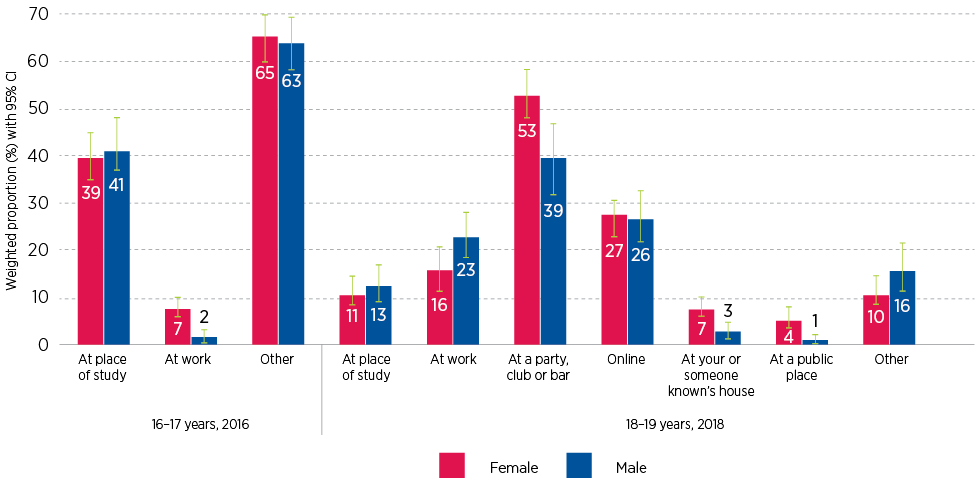

In 2016, for young people aged 16–17 years who experienced sexual harassment and reported the place of harassment, 40% reported that it happened in a place of study, of which 95% were attending school. Harassment at work was reported by 7% young of females and 2% of young males in this age group (Figure 3).2

In 2018, 2 more options were added for the place where sexual harassment was experienced. Open-text responses were also allowed for those who responded ‘other’. These open-text responses were analysed and categorised as ‘At your or someone known’s house/home’, ‘At a public place’ or ‘Other’.

Among young people aged 18–19 years who experienced harassment and reported the place of harassment, the most common place was at a party, club or bar (48% overall, 53% of females and 39% of males). Online was the second most common place (27% overall, 27% of females and 26% of males).

As young people transitioned from adolescence to young adulthood (i.e. 16–17 to 18–19 years), harassment at work increased from 5% to 18% (from 7% to 16% for females and 2% to 23% for males), whereas harassment at a place of study decreased from 40% to 12%.

The most common places that young people reported sexual harassment occurring at age 18–19 years, in 2018, may have been reported within the ‘Other’ category in 2016 (at ages 16–17 years), which accounted for 65% of responses for females and 63% for males.

Figure 3: Place where sexual harassment was experienced

Notes: Respondents could choose multiple options.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 7 and 8, weighted. Sample is restricted to those who experienced sexual harassment and reported place of harassment. n(male) = 322 (2016) and 282 (2018); n(female) = 593 (2016) and 590 (2018).

What is their relationship to the person who harassed them?

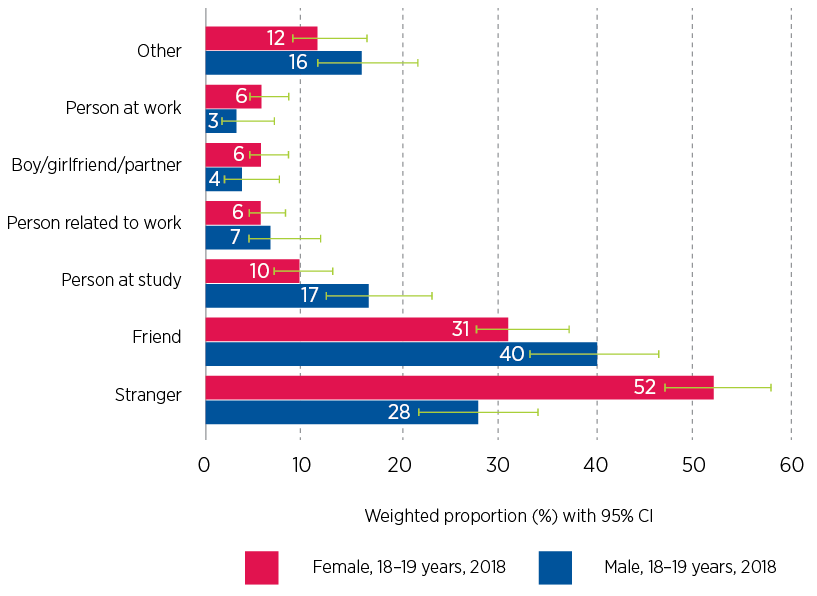

Among young people aged 18–19 years, in 2018, who had experienced sexual harassment in the past 12 months, almost all (98%) reported their relationship status to the person/s who harassed them. This was their relationship with the person(s) at the time of harassment, for all incidents in the previous 12 months. This information was not collected in 2016 (when the young people were aged 16–17 years).

For young females aged 18–19 years who had experienced sexual harassment in the past 12 months, the most common relationship to the person who harassed them was as a stranger (52%) followed by a friend (31%). Among males, this pattern was reversed with friend being the most common relationship to the person who harassed them (40%) followed by a stranger (28%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Victim’s relationship to the person who harassed them

Notes: Respondents can choose multiple options.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Wave 8, weighted. Sample is restricted to those who experienced sexual harassment and reported on their relationship to the person/s who harassed them. n(male) = 296 (2018); n(female) = 599 (2018)

What are the factors associated with sexual harassment?

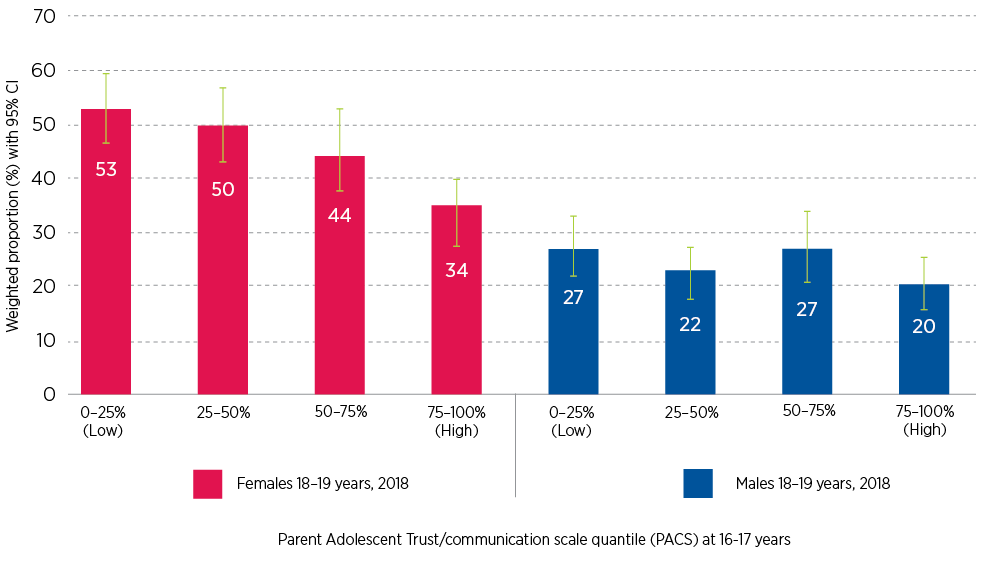

Trust and communication with parents

Having better trust and communication with parents at age 16–17 years can potentially reduce the likelihood of experiencing sexual harassment as a young adult aged 18–19 years (Figure 5 and Table S5 in supplementary materials).

- Young females: 53% who had low trust and communication with parents at age 16–17 years experienced sexual harassment at age 18–19 years, compared to 34% of those who had high trust and communication with parents at age 16–17 years.

- Young males: 27% who had low trust and communication with parents at age 16–17 years experienced sexual harassment at age 18–19 years, compared to 20% of those who had high trust and communication with parents at age 16–17 years.

The relationship between experiencing sexual harassment at age 16–17 years and trust and communication with parent at age 14–15 years was similar (Supplementary materials Table S6).

Figure 5: Proportion of young people likely to experience sexual harassment based on parent–child trust and communication

Notes: Figure shows weighted marginal probabilities of experiencing sexual harassment by level of parent and adolescent trust and communication.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 7 and 8

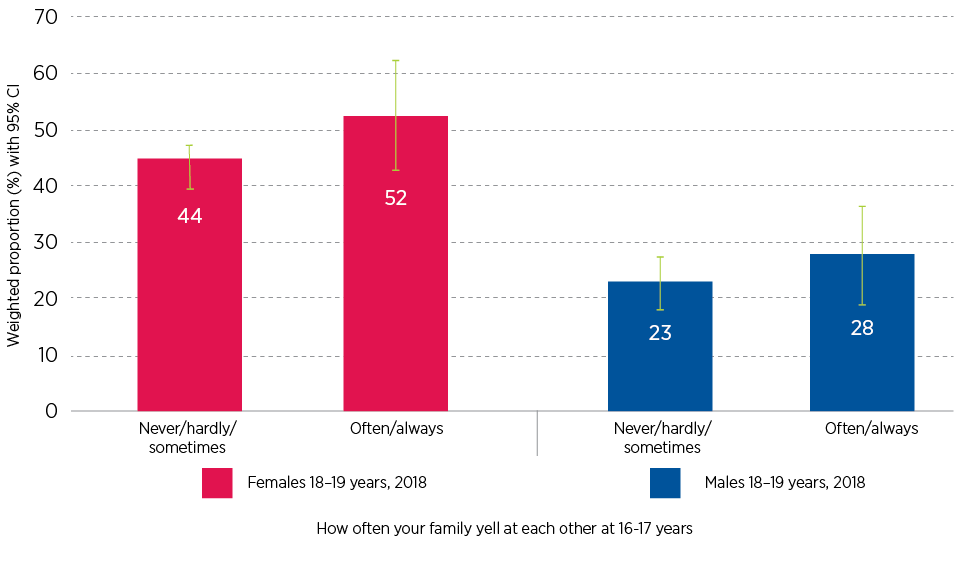

Family yells at each other

Young females aged 16–17 years with family members who never, hardly ever or sometimes yelled at each other had a reduced likelihood of experiencing sexual harassment at age 18–19 years (see Figure 6 and Table S5 of the supplementary materials).

- Young females: 52% of those aged 16–17 years with family members who often or always yelled at each other experienced sexual harassment at age 18–19 years, compared to 44% of those with family members who never, hardly ever or sometimes yelled at each other. A similar pattern was seen between experiencing sexual harassment at age 16–17 years and this factor at age 14–15 years ( Supplementary materials Table S6).

- Young males: There was not enough evidence to suggest that the proportion of young males who experienced sexual harassment differed by the frequency of yelling within the family (Supplementary materials Tables S3 and S5).

Figure 6: Proportion of young people likely to experience sexual harassment based on family cohesion

Notes: Figure shows weighted marginal probabilities of experiencing sexual harassment by levels of family cohesion.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 7 and 8

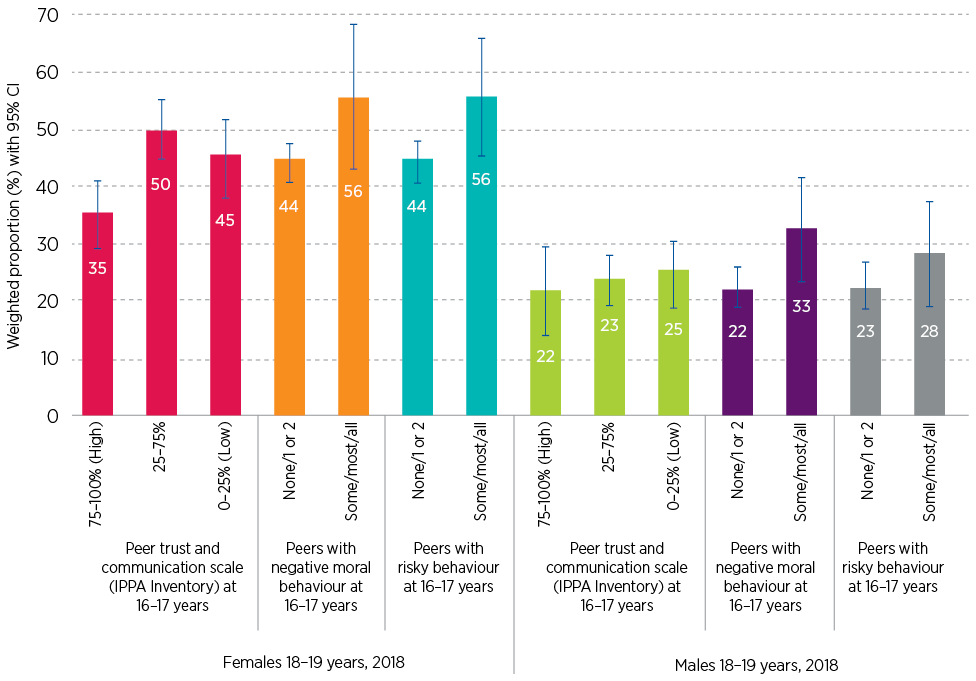

Supportive friendships and peer group behaviours

Having supportive friendships that involved trust, respect and good communication at age 16–17 years reduced the likelihood of experiencing sexual harassment among young females aged 18–19 years (Figure 7 and supplementary materials Table S5).

- Young females: 45% with poor and 50% with moderate peer trust and communication, compared to 35% with better trust and communication with their friends at age 16–17 years, experienced sexual harassment at age 18–19 years. A similar pattern was observed between experiencing sexual harassment at age 16–17 years and peer trust and communication at age 14–15 years (supplementary materials Table S5).

- Young males: The proportions of young males who experienced sexual harassment at ages 18–19 years were similar across different levels of peer trust and communication. However, better peer trust and communication reduced the likelihood of experiencing sexual harassment when they were aged 16–17 years (supplementary materials Table S6).

Characteristics of a young person’s peer group were associated with the experience of sexual harassment (Figure 7). For females, this included peers with risky behaviours such as getting into fights, using drugs, cigarettes and alcohol and breaking the law. For males, this included peers with negative moral behaviours such as being mean to others, cheating on tests and getting into trouble at school.

- Young females: 56% of those who had some, most or all peers with risky behaviours at age 16–17 years experienced sexual harassment at age 18–19 years, compared to 44% with none/one or two peers with these behaviours. The pattern was similar for females aged 16–17 years.

There was evidence to suggest that peers’ negative moral behaviours at age 16–17 years were associated with the experience of sexual harassment at age 18–19 years (supplementary materials Table S3 and S5). Similarly, they were associated with experiencing sexual harassment when they were younger at age 16–17 years (supplementary materials Table S6).

- Young males: Peers’ negative moral behaviours but not peers’ risky behaviours were associated with the experience of sexual harassment. One-third (33%) of those who had some, most or all peers with negative moral behaviours at age 16–17 years experienced sexual harassment at age 18–19 years, compared to 22% of males with none, one or two peers with these behaviours. The pattern was similar for males aged 16–17 years (supplementary materials Table S6).

Figure 7: Proportion of young people likely to experience sexual harassment based on peer-related predictors

Notes: Figure shows weighted marginal probabilities of experiencing sexual harassment by levels of peer trust and communication.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 7 and 8

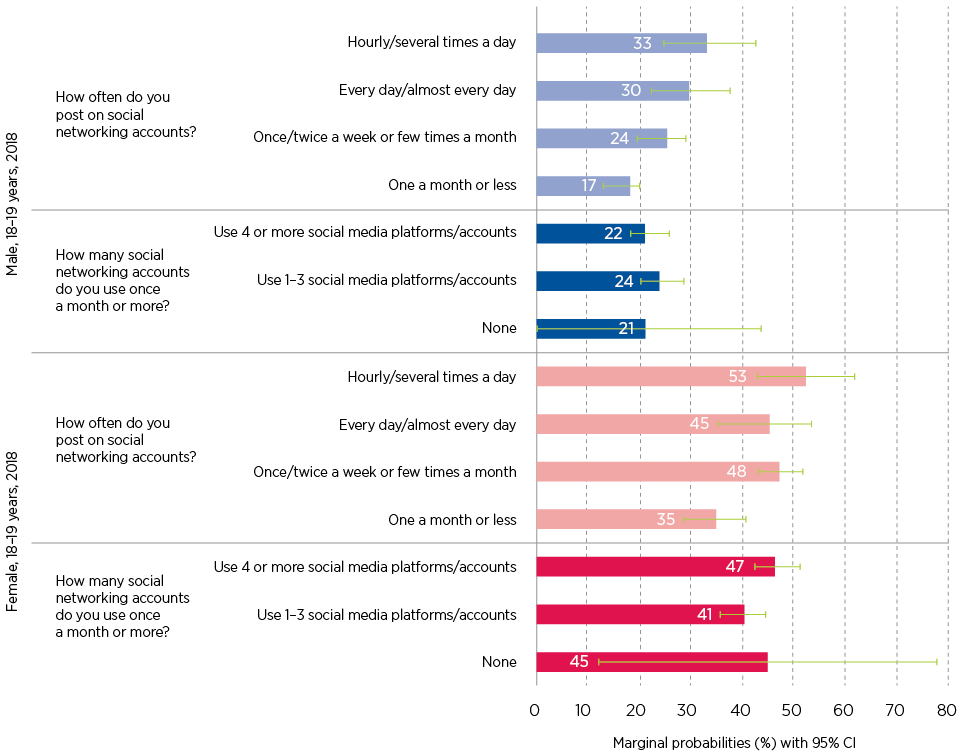

Frequency of posting and sharing on social media

Sharing or posting on social networking sites more than once a month was associated with the increased likelihood of experiencing sexual harassment for young females and males aged 18–19 years, in 2018 (Figure 8). For example, 53% of females and 33% of males who shared or posted on social media hourly or several times a day experienced some form of sexual harassment, compared to 35% of females and 17% of males respectively who posted or shared on social media once a month or less (supplementary materials Table S5). There was not enough evidence to suggest an association between the number of social network accounts young people had and the experience of sexual harassment (supplementary materials Table S5).

Figure 8: Proportion of young people likely to experience sexual harassment based on frequency of social media use

Notes: Figure shows weighted marginal probabilities of experiencing sexual harassment by frequency of posting and sharing on social media.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 7 and 8

Engaging in sexual harassment

Data on engaging in sexual harassment were collected at age 16–17 years along with young people’s experience of sexual harassment. They were asked to report whether they had engaged in any of 3 behaviours in the past 12 months. Overall, 8% of females and 12% of males reported having engaged in any of 3 types of sexual harassment at age 16–17 years.3

Engaging in sexual harassment at age 16–17 years was associated with experiencing sexual harassment at aged 18–19 years (supplementary materials Table S5).

- Young females: Among those who engaged in and experienced sexual harassment at the age of 16–17 years, 67% experienced sexual harassment at the age of 18–19 years. The likelihood of experiencing sexual harassment at age 18–19 years was similar (69%) among those who engaged in but did not experience sexual harassment at the age of 16–17 years. The likelihood then reduced to 58% for those who were not engaged in but experienced sexual harassment and reduced further to 32% for those who did not engage in nor experience sexual harassment at 16–17 years.

- Young males: 34% of those who engaged in and/or experienced sexual harassment at the age of 16–17 years experienced sexual harassment at the age of 18–19 years, compared to 17% of those who did not engage in nor experience sexual harassment at 16–17 years.

Experience of sexual harassment among young LGBTQ+ and non-LGBTQ+ people

Prevalence, where it happened, and relationship to the person who harassed them

Young people aged 18–19 years in 2018 who identified as being gender and sexually diverse or gender non-confirming (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and/or queer (LGBTQ+)) were more likely to report having experienced sexual harassment (49%) in the past 12 months than those who identified as non-LGBTQ+ (31%).4 In addition, young LGBTQ+ people were more likely to experience multiple types of sexual harassment (36%) compared to young non-LGBTQ+ people (20%).

Among young LGBTQ+ people, females were more likely to report experiencing sexual harassment (59%) in the past 12 months than males (29%). The most common form of harassment was ‘someone making sexual gestures, rude remarks, touching or looking at the person in a way that embarrassed or upset the receiver,’ which was reported by 34% of young LGBTQ+ people compared to 22% of young non-LGBTQ+ people. Similarly, almost one-third of young LGBTQ+ people (32%) and 2 in 10 young non-LGBTQ+ people reported ‘someone telling, showing or sending sexual pictures, stories or jokes that made the receiver uncomfortable.’

Among both young LGBTQ+ and non-LGBTQ+ people who experienced sexual harassment and reported on their:

- place of harassment, the most commonly reported place was a party, club or bar (46% and 49% respectively). Although ‘online’ was the second most common place for both groups, a higher proportion of young LGBTQ+ people reported online harassment (36%) compared to young non-LGBTQ+ people (24%).

- relationship to the person(s) who harassed them, the most common relationship was a stranger (50% and 42% respectively), followed by a friend (29% and 36% respectively).

More information on the findings in this section are in supplementary materials, Tables S7–S9.

Factors associated with sexual harassment

Having better trust and communication with parents at age 16–17 years, in 2016, reduced the likelihood of experiencing sexual harassment among both young LGBTQ+ and non-LGBTQ+ people aged 18–19 years, in 2018 (supplementary materials Table S10). For example, among young LGBTQ+ people, 60% who had low trust and communication with parents at age 16–17 years experienced sexual harassment at age 18–19 years, compared to 42% of those who had high trust and communication with parents at age 16–17 years.

We did not find sufficient evidence that different levels of yelling within the family and peer trust and communication were associated with the risk of experiencing sexual harassment among young LGBTQ+ or non-LGBTQ+ people. There was also not enough evidence to suggest an association between other characteristics of peer groups such as moral and risky behaviours and the experience of sexual harassment for either of the groups.

Sharing or posting on social networking sites more than once a month was associated with an increased likelihood of experiencing sexual harassment for both young LGBTQ+ and non-LGBTQ+ people at age 18–19 years. For example, 60% of young LGBTQ+ people and 40% of young non-LGBTQ+ people experienced sexual harassment if they shared or posted on social media hourly or several times a day, compared to 36% of young LGBTQ+ people and 22% of young non-LGBTQ+ people who posted once a month or less.

Among young LGBTQ+ people who engaged in and experienced sexual harassment at age 16–17 years, 74% experienced sexual harassment at age 18–19 years. The likelihood decreased to:

- 67% for those who were not engaged in but experienced sexual harassment at age 16–17 years

- 59% for those who were engaged in but did not experience sexual harassment at age 16–17 years

- 40% for those were not engaged and did not experience sexual harassment at 16–17 years.

Similar patterns were observed for young non-LGBTQ+ people (supplementary materials Table S10).

Relevance for policy and practice

Addressing levels of sexual harassment experienced by young people is critical, particularly for young females and young LGBTQ+ people

We found that the prevalence of sexual harassment is high among young people, particularly for young females and young LGBTQ+ people. These findings, albeit from data that are now 6 years old, address a key data gap on the experience of sexual harassment among young people in Australia aged 19 years or less. These findings also confirm the importance of women and LGBTIQA+ people as 2 of the priority groups in the National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children (Department of Social Services (DSS), 2022).

To better address the high prevalence of those experiencing sexual harassment, we also need data on people who engage in this harassment, which is currently limited. Further data collection on people who engage in sexual harassment is warranted to better inform future policy and practice.

Sites where sexual harassment is more commonly reported by young people require further research attention

There is limited information in LSAC on engagement in sexual harassment. Hence, we examined the information that was collected about where sexual harassment was experienced as reported by the victim-survivors in this instance. We found that:

- Around 2 in 5 young people at age 16–17 years who experienced sexual harassment reported that it happened at their place of study. Research indicates that young people at age 16–17 years who were harassed at an educational institution were more likely to report that it was their peers or fellow students who harassed them (AHRC, 2017; Lei et al., 2020). This supports the need to ensure education about healthy sexual relationships is delivered in schools.

- Around 1 in 4 young people at age 18–19 years reported experiencing sexual harassment online. With increasingly more people interacting online, the prevalence is likely to be considerably higher in 2024 and therefore a focus on preventing online sexual harassment is needed.

- Around half of young females and 2 in 5 young males at age 18–19 years reported experiencing sexual harassment at a party, club or bar. A focus on preventing sexual harassment in these external social environments is also needed to facilitate safe and respectful environments for young people.

Policies and programs that support positive communication between parents and their children in adolescence may also reduce the likelihood of experiencing sexual harassment

We identified that trust and communication with parents, family members who do not yell at each other, and supportive friendships through adolescence reduced the likelihood of young people experiencing sexual harassment in early adulthood. These factors have also been identified as protective factors against intimate partner violence and cyberbullying (O’Donnell et al., 2023; Rioseco & Vassallo, 2021). The findings suggest policies and programs that support positive communication between parents and their children in adolescence may assist in reducing the likelihood of young people experiencing sexual harassment.

Potential of Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC)

This study explored the factors associated with experiencing sexual harassment as they are central to informing future interventions and programs. Many related and important questions could be addressed with current and future waves of LSAC data.

Currently, LSAC has only collected data on people engaging in sexual harassment behaviours at age 16–17 years (for the K cohort). We are planning to collect more data in Wave 11 on people who experience sexual harassment, which will allow researchers to examine the following:

- how the prevalence of sexual harassment has changed overtime and the groups of young people more at risk

- how the forms, place and relationship to perpetrator of sexual harassment have changed over time

- factors associated with online and offline harassment among young adults.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2021–22). Sexual harassment. ABS. www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/crime-and-justice/sexual-harassment/lat....

Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC). (2017). Change the course: National report on sexual assault and sexual harassment at Australian universities. Redress, 26(2), 27–29.

Bolduc, M. L., Martin-Storey, A., & Paquette, G. (2023). Correlates of sexual harassment victimization among adolescents: A scoping review. Journal of Social Issues, 79(4), 1147–1173.

Department of Social Services (DSS). (2022). National plan to end violence against women and children 2022–2032. Canberra: DSS, Commonwealth of Australia.

Douglass, C. H., Wright, C. J. C., Davis, A. C., & Lim, M. S. C. (2018). Correlates of in-person and technology-facilitated sexual harassment from an online survey among young Australians. Sexual Health, 15(4), 361–365. doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1071/SH17208

eSafety Commissioner. (2018). State of play — Youth, Kids and digital dangers. Canberra: Australian Government.

eSafety Commissioner. (2022). Cool, beautiful, strange and scary: The online experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and their parents and caregivers. Canberra: Australian Government.

eSafety Commissioner. (2023). A new playground: The digital lives of young people with disability. Canberra: Australian Government.

eSafety Commissioner. (2024). Tipping the balance: LGBTIQ+ teens’ experiences negotiating connection, self-expression and harm online. Canberra: Australian Government.

Heywood, W., Myers, P., Powell, A., Meikle, G., & Nguyen, D. (2022). National Student Safety Survey: Report on the prevalence of sexual harassment and sexual assault among university students in 2021. Melbourne: The Social Research Centre.

Lei, X., Bussey, K., Hay, P., Mond, J., Trompeter, N., Lonergan, A. et al. (2020). Prevalence and correlates of sexual harassment in Australian adolescents. Journal of School Violence, 19(3), 349–361.

O’Donnell, K., Rioseco, P., Vittiglia, A., Rowland, B., & Mundy, L. (2023). Intimate partner violence among Australian 18–19 year olds. (Growing Up in Australia Snapshot Series – Issue 11). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Rioseco, P., & Vassallo, S. (2021). Adolescents online. (Growing Up in Australia Snapshot Series – Issue 5). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Warren, D., & Swami, N. (2018). Teenagers and sex. In G. Daraganova and N. Joss (Eds.), Growing Up In Australia – The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children, Annual Statistical Report 2018. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Ybarra, M. L., & Mitchell, K. J. (2008). How risky are social networking sites? A comparison of places online where youth sexual solicitation and harassment occurs. Pediatrics, 121(2), e350–e357. doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-0693

Further details

Supplementary materials

Technical details of this research, including description of measures, detailed results and bibliography are available to download as a PDF [256 kB]

About the Growing Up in Australia snapshot series

Growing Up in Australia snapshots are brief and accessible summaries of policy-relevant research findings from Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC). View other Growing Up in Australia snapshots in this series.

1Based on 95% confidence intervals of the estimates (i.e. marginal probabilities and odds ratios) and p values.

2In 2016, according to LSAC data, 48% of Australian school students aged 16–17 years were in part-time paid employment, with almost 90% working less than 15 hours per week (Evans-Whipp et al., 2021)

3Previous analysis of LSAC data on sexual engagement reported on the association between sexual engagement and age of first viewing pornography and is available in Warren and Swami (2018).

4LBGTQ+ data were not collected at the age of 16–17 years in Wave 7, in 2016. Thus, this section only presents data from Wave 8, in 2018.

Acknowledgements

Authors: Dr Neha Swami, Kathryn Apeness, Catherine Andersson, Dr Monsurul Hoq

Swami, N., Apeness, K., Andersson, C., & Hoq, M. (2024). Experience of sexual harassment among young Australians: Who, where and how? (Growing Up in Australia Snapshot Series – Issue 12). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Copy editor: Katharine Day

Graphic design: Rachel Evans

This snapshot benefited from contributions from the eSafety Commissioner and the Department of Social Services (Research, Evaluation and Data section of Ending Gender Based Violence Group; and Longitudinal Studies – Research Methods, Data Strategy Branch).

This research would not have been possible without the invaluable contributions of the Growing Up in Australia children and their families.

Publication details

Swami, N., Apeness, K., Andersson, C., & Hoq, M. (2024). <i>Experience of sexual harassment among young Australians: Who, where and how?</i> (Growing Up in Australia Snapshot Series – Issue 12). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.