Children's views about parental separation

Children's views about parental separation

2.1 Introduction

In a sense, the old adage that children are to be "seen and not heard" reflects the way in which decisions were traditionally made about children's care and living arrangements associated with parental separation. Although this approach may have been in part to protect children from any distress associated with reporting their experiences and preferences, it may also have been influenced by a belief that, until they are around 12 years old, children tend to have much difficulty articulating their views about their lives and making meaningful contributions to decision-making about issues affecting their welfare (for a review, see Pryor & Emery, 2004).

Despite the "misgivings" about the decision-making capacities of children and adolescents, several authors have referred to a growing recognition that children in general are more competent in understanding and articulating their feelings and preferences than previously believed, and that their voices provide important insights that can improve decisions affecting them (Green & Hill, 2005; Parkinson & Cashmore, 2008; Pryor & Emery, 2004; Smith, Taylor, & Tapp, 2003). In line with this development, children's views are now often taken into account in family law proceedings in Australia and several other countries, a practice that Smart (2005) described as "a sudden rush of enthusiasm to hear children's voices" (p. 307).

The recency of this recognition seems surprising given that it is now more than 25 years since the United Nations (UN) General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), which among many other things, emphasised children's right to express their views freely on matters that affect them and to have their views taken into account in decision-making (Article 12).1

The value of taking account of children's views of their experiences and preferences is further reinforced by research suggesting that:

- the levels of agreement between the reports of parents and their children on various aspects of their children's wellbeing are by no means strong;

- factors identified to help explain children's wellbeing can vary according to whether the children or parents provide the wellbeing assessments; and

- regardless of the accuracy of their interpretation of their circumstances, these interpretations will have profound effects on their emotional reactions and behaviour (see Achenbach, McConaughy, & Howell, 1987; Baxter, Weston, & Qu 2011; Cremeens, Eiser, & Blades, 2007; Youngstrom, Loeber, & Stoughamer-Loeber, 2000).

Halpenny, Greene, and Hogan (2008) interviewed a group of children of separated parents aged 8-17 years in Ireland and concluded that these participating children provided sophisticated descriptions of their experience of parental separation and the effects of this on their lives, and clearly had "the ability to review and revise their own perspectives and understanding of what happened within their family" (p. 321). The study highlighted that children had different ways of coping with parental separation and different needs for support. Similarly, based on a qualitative study of a group of Australian children aged 7-17 years whose parents were separated, Campbell (2008) found that the children knew more about their parents' difficulties than the parents and other adults realised, and suggested that the stress of parental separation experienced by children might be alleviated to some extent if children's views were heard by their parents and others. Similarly, reflecting on transcripts of discussions with young children,2 Moloney (2005) argued that "children can be wiser than many of us might imagine" (p. 217).

Also in Australia, Lodge and Alexander (2010) examined the reports of 623 adolescents aged 12-18 years whose parents had separated after July 2006. They found that the majority of these adolescents said they had wanted to participate in decisions about their living arrangements and many believed that they did have a say on this matter. Similar findings have been reported by some other Australian studies (Campo, Fehlberg, Millward, & Carson, 2012; Cashmore & Parkinson, 2008; Parkinson, Cashmore, & Single, 2005).

Taken together, these various studies highlight the importance of taking into account the views of children, as emphasised in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. In relation to children of separated parents, this approach provides a more nuanced understanding of parenting matters and children's adjustment after parental separation - a point noted by Campo et al. (2012) and Weatherall and Duffy (2008).

This chapter focuses mainly on the personal reports of children (aged 12-13 years) about their experiences of parental separation. The following issues are addressed:

- How did the children feel about their parents' separation?

- How did these children whose parents had separated describe the quality of the relationship between their separated parents?

- To what extent were these children's perceptions similar to those held by their parents?

- To what extent were these children's perceptions similar to those of other children in LSAC whose parents were living together?

- What proportion of children with separated parents wanted and believed they did have input into decisions affecting their living arrangements?

- How did the children with separated parents feel about their care-time arrangements? For example, what proportion felt that they were spending sufficient time with the parent who was identified as "living elsewhere", and what proportion believed that they had participated in decisions about their living arrangements?

- To what extent, if at all, do children's views about their parents' separation differ according to the following factors:

- the children's gender;

- the duration of parental separation; and

- their care-time arrangements?

2.2 Data

In Wave 5 of the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC), children in the K cohort (aged 12-13 years) were asked about a wide range of issues via audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) when in the presence of an interviewer. This was the first wave in which K cohort children whose parents had separated were asked a series of questions regarding their views about their parents' separation. Their responses to these questions form the focus of this chapter. (B cohort children were not asked these questions.)

There were 901 K cohort children with a parent living elsewhere from their primary carer.3 Of these children, the 726 who had completed the module on parental separation represent the sample on which this chapter is based. Although the parents of some of these children may have never lived together, they are described as "separated parents" in this chapter for the sake of succinctness.

The 175 children from separated families who did not answer any questions in the module on parental separation include 38 whose primary carer did not give consent for the study child to be invited to participate. Those who completed the module and those who did not were similar in terms of gender profile, but differed significantly in relation to their care-time arrangements and age at parental separation. (The development of the latter variable is described later in this section.) Compared with the children who completed the module, those who did not do so were more likely to have not seen their father in the previous 12 months (33% vs 15%) and to have either experienced parental separation when they were infants (i.e., less than 1 year old) (46% vs 38%) or never lived with both parents (13% vs 6%). In other words, the results in this chapter may not be representative of all the children who had one parent living elsewhere from their primary carer.

One set of analyses in this chapter compares children's perceptions of the quality of the relationship between their parents with the reports of each of their parents. The parents are here classified as "resident" or "non-resident" according to whether they have been identified in LSAC as: (a) living with the child and knowing the child best and thereby becoming the "primary" parent-informant; or (b) living elsewhere. Some children spent 35-65% of nights with each parent (classified by the Child Support Agency as being in "shared care"), but for the purposes of the present analyses, these children were classified as having a "resident parent" and "non-resident parent".4 Some resident parents decided to skip the module on separation and parenting. Of the 726 children, 696 resident parents (631 mothers and 65 fathers) completed the module, and 392 non-resident parents (351 fathers and 41 mothers) were interviewed. Information provided by these parents is included in the analyses. However, non-resident parents who had not had face-to-face contact with their study child in the previous 12 months were not interviewed. These parents accounted for more than one-half of the non-resident parents who did not participate in Wave 5. It is worth noting that higher proportions of non-resident parents who were not interviewed than those who were interviewed had separated when the study child was under 1 year old (44% vs 35% respectively) or were not living with the child's mother when the child was born (11% vs 3% respectively).

This chapter also examines whether children's views about parental separation varied according to their gender, care-time arrangements and age at parental separation (with the latter reflecting the duration of their parents' separation). Both children and resident parents were asked about the nature of their care-time arrangements. The patterns of arrangements reported by each party were subsequently used in the analyses of the extent to which children's views of parental separation varied according to their care-time arrangements. For this reason, the first set of findings below summarises the care-time patterns that were reported by children and their resident parent.

The age of children at parental separation was derived from resident parents' reports on the age their child was when he or she last lived with both biological parents. Where resident parents did not provide this information and the separation occurred between waves, their child's age at parental separation was set at the mid-point between the two waves.5 Children were divided into four groups according to their age at parental separation: less than 1 year (applying to 44% of the children), 1-4 years (15%), 5-9 years (23%), and 10+ years (18%).6

2.3 Patterns of care-time arrangements reported by children and resident parents

Children were asked to indicate which parent they mostly or only lived with.7 Around three in four (73%) nominated their mother, around one in ten (9%) nominated their father, and around one in five (19%) reported that they spent (roughly) equal time with each parent.

Resident parents provided more detailed information about their child's care-time arrangements. On the basis of the reports of resident parents, the following patterns of care-time arrangements emerged:

- 15% of the children had not seen their father in the past year;

- 16% spent only daytime hours with their father;

- 16% spent 1-13% of nights with their father;8

- 36% spent 14-34% of nights with their father;

- 10% were in a shared care-time arrangement (covering 35-65% of nights with each parent); and

- 2% spent most or all nights with their father (66-100% of nights).

These categories roughly correspond with those developed by the Australian Government Department of Human Services - Child Support, for the assessment of child support liability.9 There was no statistically significant difference in care-time arrangements between boys and girls according to reports of both children themselves and resident parents.

2.4 Children's views about the separation of their parents

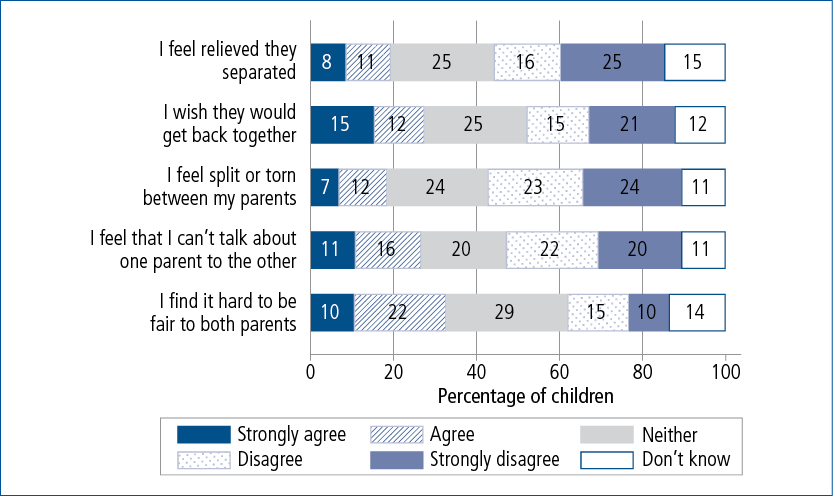

Children were asked to indicate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with each of five statements relating to their parents' separation: (a) I feel relieved they separated; (b) I wish they would get back together; (c) I feel split or torn between my parents; (d) I feel that I can't talk about one parent to the other; and (e) I find it hard to be fair to both parents. Six response options were provided to the children: strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, strongly disagree, and don't know. Figure 1 shows the patterns of answers provided by the children for each of the statements.

The statements "I feel relieved they separated" and "I wish they would get back together" focus on how children feel about the separation per se, whereas the other three statements focus on issues relating to difficulties children may have in handling inter-parental sensitivities arising from the breakdown of the relationship. This is particularly the case for the statements "I feel that I can't talk about one parent to the other" and "I find it hard to be fair to both parents".

Although the two issues "I feel relieved they separated" and "I wish they would get back together again" seem to take a somewhat opposing stance, these statements more commonly generated disagreement (strongly or otherwise) than agreement: 36-41% disagreed with each, while 19% agreed that they felt relieved about the separation and 27% agreed that they wished their parents would get back together. Around one-quarter indicated that they neither agreed nor disagreed with each statement (taken separately) and 12-15% selected the "don't know" option.

Disagreement was also more commonly expressed than agreement for two of the other three statements. Of the five statements, the one that was most commonly "rejected" was "I feel split or torn between my parents". Nearly one-half of the children (47%) disagreed with this statement, 19% agreed, 24% said they neither agreed nor disagreed, and 11% selected the "don't know" option.

The remaining statement that was more likely to be "rejected" than "accepted" was "I feel that I can't talk about one parent to the other". Although 42% disagreed with this statement, 27% agreed, with the remainder responding that they neither agreed nor disagreed (20%) or didn't know (11%).

The statement "I find it hard to be fair to both parents", was the only one which generated greater agreement than disagreement. Around one-third of the children (32%) agreed with this statement and one-quarter (25%) disagreed. On the other hand, 29% selected the "neither agree nor disagree" option and 14% indicated that they were not sure about this matter.

What does this all mean? Firstly, the response options "neither agree nor disagree" or "don't know" were fairly common across these different statements, applying to 31-43% of children (neither agree nor disagree: 20-29%; don't know: 11-15%). Secondly, for children who indicated agreement or disagreement, the most common responses were: not feeling split or torn between the parents (47% of all children), feeling able to talk to each parent about the other (42%), not feeling relieved that they separated (41%), not wishing that their parents would get back together again (36%), and finding it hard to be fair to both parents (32%). It seems reasonable to suggest then, that children were more inclined to have accepted the separation and to be handling the need to deal with each parent well. However, a substantial minority wished their parents would get back together again and/or had difficulties in dealing with each parent in some way, especially in being fair to both parents or in feeling comfortable regarding talking about one parent to the other.

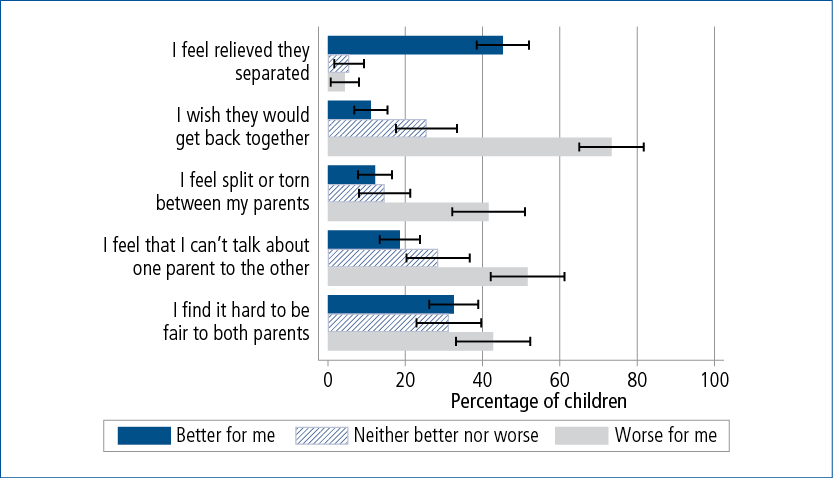

Children were also asked: "Do you think it was better for you that your parents separated, or do you think it would have been better for you if they stayed together?" Children were nearly twice as likely to indicate that separation was the better of the two alternatives for them. One-third (34%) said that their parents' separation was better for them, while nearly one in five (18%) considered that it would have been better for them had their parents stayed together. The remainder, representing around half the children (48%), either said that neither would have been worse or better for them (18%) or responded with "don't know" (30%). The high uncertainty rate about this issue is not surprising given that the parents of many of the children in this sample had separated when the children were very young (44% of the children were under 1 year at the time, and another 15% were 1-4 years old).

The views of children on parental separation (Figure 2.1) varied according to their overall evaluation of whether their parents' separation was better for them, whether they would have been better off had their parents stayed together, or whether neither alternative resulted in their being better off.

Figure 2.1: Children's level of agreement or disagreement with statements about their parents' separation, K cohort, Wave 5

Notes: Some children responded to some items but skipped others. Response sizes ranged from 710 to 714.

As shown in Figure 2.2, children who felt that parental separation was better for them were more likely than the other two groups to feel relieved by the separation (45% vs 4-7%), and children who believed that they would have been better off had their parents stayed together were much more likely than the other groups to report that they wished their parents would get back together (73% vs 12-26%). In addition, those who believed that they would have been better off had their parents stayed together were more likely than the other two groups to indicate that they: felt split or torn between their parents (42% vs 12-15%), and felt that they could not talk about one parent to the other (52% vs 19-29%). Their views on being fair to both parents did not differ significantly (43% vs 31-33%).

Although it is not possible to identify causal connections between these factors, difficulties in handling inter-parental sensitivities may have contributed to children's overall assessments that they would have been better off had their parents stayed together. Nevertheless, many other post-separation experiences are likely to have influenced such beliefs, including possible increases in financial hardship, relocation, distance between the two homes, a parent re-partnering, and so on.

Figure 2.2: Proportion of children who agreed with statements about their parents' separation, by whether they thought the separation was better for them, K cohort, Wave 5

Notes: Sample sizes: better for me, n = 246; neither, n = 133; worse for me, n = 127. For each group, numbers of children on which percentages were based may vary slightly due to refusals to individual items. Confidence intervals are shown by the horizontal line extending beyond each bar. A lack of overlap (or slight overlap)a in the confidence intervals for comparison groups indicates that the values are statistically significantly different at p < .05.

a According to Cumming and Finch (2005, p. 180), when the proportion of overlap, expressed as a proportion of the average length of margin of the two groups, is 50% or less, the difference in means between the two independent groups is statistically significant at the 5% level.

Simplifying children's responses to parental separation statements

Much of the rest of this chapter focuses on the extent to which children's views on the above matters varied according to their personal characteristics, such as gender, care-time arrangements and age at parental separation. In order to simplify the results, two scales were derived from five of the items. The first scale, regarding feeling relief about the parental separation, was based on two items: feeling relieved that the parents had separated; and wishing that they would get back together. The second scale, reflecting a sense of divided loyalties, was based on the other three items: feeling split or torn between parents; feeling unable to talk about one parent to the other; and finding it hard to be fair to both parents. With the exception of one item, children's responses on these items were assigned a rating from "1" (strongly disagree) to "5" (strongly agree). The exception related to children's responses concerning wishing that their parents would get back together. Here, ratings were reversed, so that "1" represented strong agreement and "5", strong disagreement. Each child's average rating across the component items in each derived scale was then determined, resulting in scores ranging from 1.0 to 5.0 for each of the two derived scales. Higher scores on the first scale indicate a greater sense of relief and a lower desire for parents to get back together. Higher scores on the second scale, on the other hand, reflect a greater feeling of divided loyalties in relation to the parents.10 The following results focus on the proportion of children with relatively high scores (ranging from 3.5-5.0) on the two derived scales.

It is worth noting that the item concerning children's level of agreement with the statement that their parents' separation was better for them or worse for them was not considered in the two scales for the following reasons: (a) this item was not presented to the children as part of the set of five items; and (b) the response options differed from those of the other statements. Given that the way in which the patterns of children's responses to this item varied according to the selected characteristics examined were largely consistent with those based on the first scale (concerning relief about parental separation), the results are not shown in the following discussion.

Children's views about their parents' separation, by child gender, care-time arrangements, and age at separation

This section examines the extent to which children's views varied according to their gender, care-time arrangements and age when their parents separated. Given that all the children were 12-13 years old, their age at parental separation was treated as a proxy for duration of parental separation.

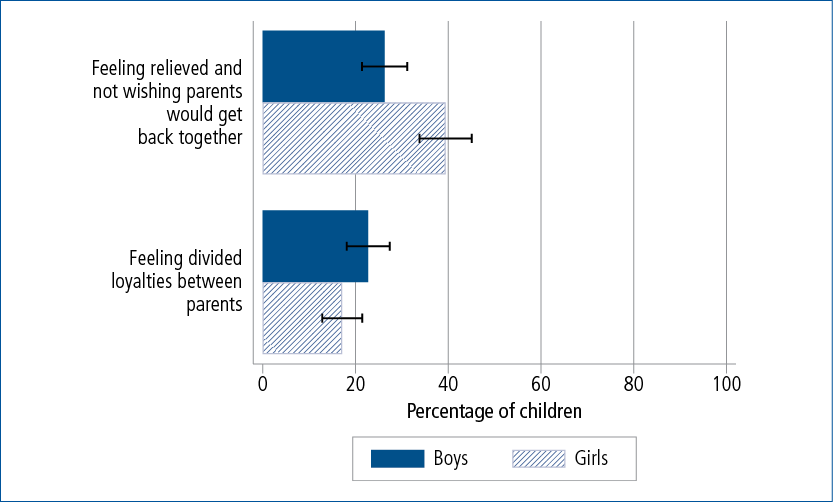

Figure 2.3 summarises the results for boys and girls. Girls were more likely than boys to feel relieved about their parents' separation (with little desire for their parents to get back together) (39% vs 26%), while also seeming slightly less likely than boys to experience divided loyalties (17% vs 23%). However, the latter result did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 2.3: Proportions of children who felt relieved or had divided loyalties about their parents' separation, by child gender, K cohort, Wave 5

Notes: Sample sizes: boys, n = 369; girls, n = 341. Confidence intervals are shown by the horizontal line extending beyond each bar. A lack of overlap in the confidence intervals for comparison groups (or slight overlap - see note a in Figure 2.2) indicates that the values are statistically significantly different at p < .05. Scores ranged from 1.0-5.0, with scores of 3.5-5.0 here taken as reflecting agreement.

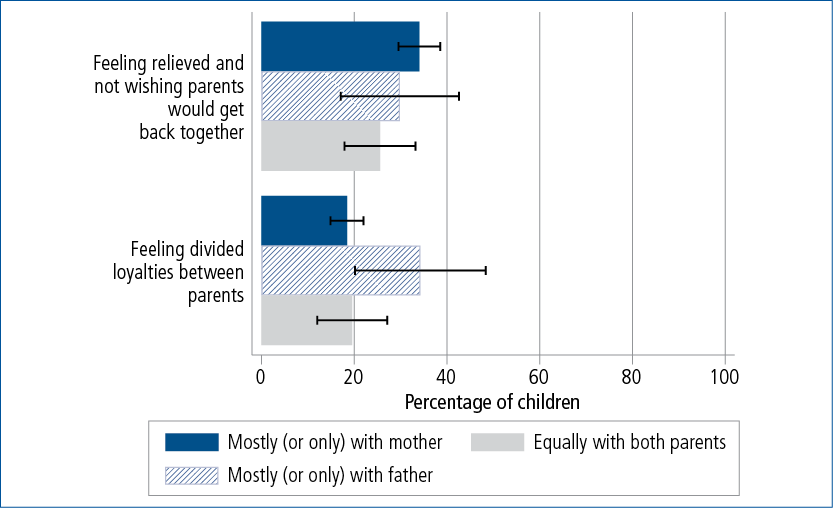

The extent to which children's views about their parents' separation varied according to their care-time arrangements, as described by the children, is summarised in Figure 2.4. Children were divided into three groups according to whether they indicated that they mostly/only lived with their mother or father or whether they lived for an equal time with both parents. Children who reported living mostly or only with their father were more likely than children in the other two care-time arrangements to indicate experiencing divided loyalties (34% vs 18-20%), while trends for children with the other two living arrangements were very similar. A higher proportion of children who lived mostly or only with their mother compared to those in the other two groups expressed feeling relieved about their parents' separation and not wishing that their parents would get back together (34% vs 26-30%), although this result was not statistically significant.

Figure 2.4: Proportions of children who felt relieved or had divided loyalties about their parents' separation, by children's reports of which parent they mostly lived with, K cohort, Wave 5

Notes: Sample sizes: with mother, n = 505; with father, n = 57; equally with both parents, n = 136. Confidence intervals are shown by the horizontal line extending beyond each bar. A lack of overlap in the confidence intervals for comparison groups (or slight overlap - see note a in Figure 2.2) indicates that the values are statistically significantly different at p < .05. Scores ranged from 1.0-5.0, with scores of 3.5-5.0 here taken as reflecting agreement.

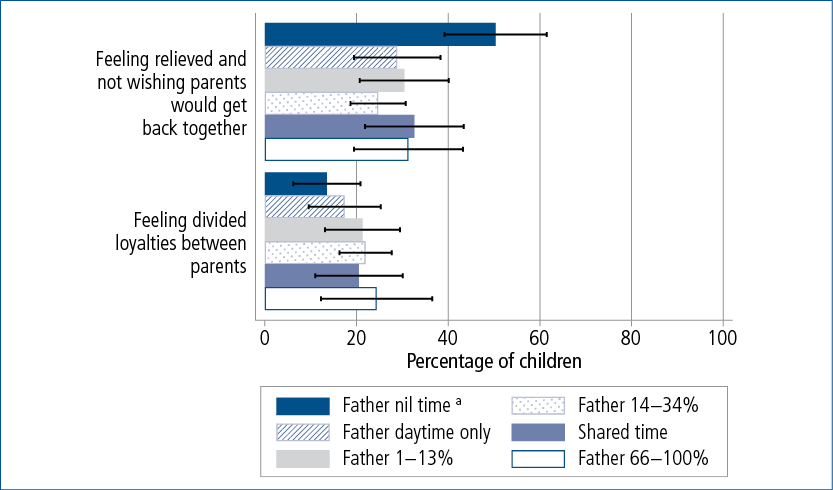

The views of children in the care-time arrangements identified on the basis of the resident parents' reports are presented in Figure 2.5. Children who had not seen their father in the previous 12 months were significantly more likely than children in other care-time arrangements to express relief about the separation, with little desire for parental reconciliation (50% vs 25-33%). Children who had not seen their father in the previous 12 months also seemed less likely than other children to experience divided loyalties, though the results were not statistically significant.

Figure 2.5: Proportions of children who felt relieved or had divided loyalties about their parents' separation, by care-time arrangements reported by their resident parent, K cohort, Wave 5

Notes: a "Father nil time" refers to seeing the child less than once a year or not at all, "shared time" refers to 35-65% of nights with each parent. Sample sizes: father nil time, n = 90-91; father daytime only, n = 106; father 1-13% nights, n = 112; father 14-34% nights; n = 225-226; shared time, n = 86; father 66-100% nights, n = 63. For each care-time group, numbers of children on which percentages were based may vary slightly due to non-response to individual items. Confidence intervals are shown by the horizontal line extending beyond each bar. A lack of overlap in the confidence intervals for comparison groups (or slight overlap - see note a in Figure 2.2) indicates that the values are statistically significantly different at p < .05. Scores ranged from 1.0-5.0, with scores of 3.5-5.0 here taken as reflecting agreement.

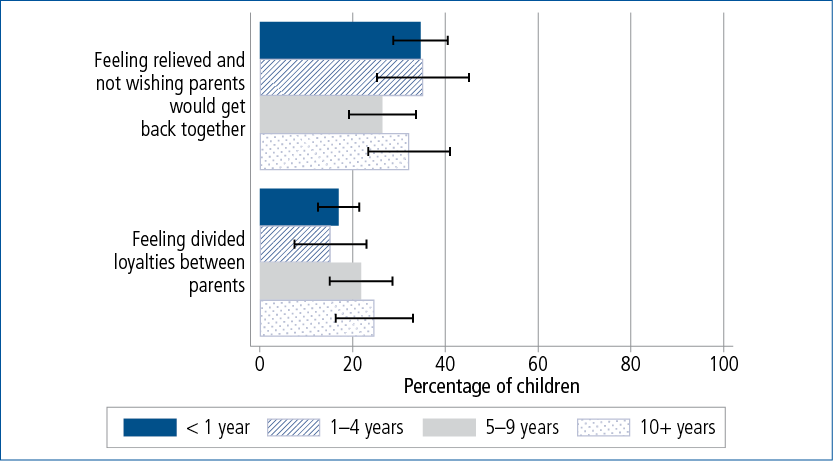

Figure 2.6 presents children's views on parental separation according to their age at the time their parents separated. Children's views on all three issues pertaining to parental separation did not vary significantly according to how old they were when their parents separated.

Figure 2.6: Proportions of children who felt relieved or had divided loyalties about their parents' separation, by their age at separation, K cohort, Wave 5

Notes: Sample sizes: < 1 year, n = 298 (including 36-38 children whose parents had never lived together or had separated before they were born); 1-4 years, n = 103; 5-9 years, n = 166; 10+ years, n = 126. For each group, numbers of children on which percentages were based may vary slightly due to refusals to individual items. Confidence intervals are shown by the horizontal line extending beyond each bar. A lack of overlap in the confidence intervals for comparison groups (or slight overlap - see note a in Figure 2.2) indicates that the values are statistically significantly different at p < .05. Scores ranged from 1.0-5.0, with scores of 3.5-5.0 here taken as reflecting agreement.

2.5 Children's perceptions of the quality of the inter-parental relationship

Regardless of whether their parents were living together or apart, all K cohort children were asked how they would best describe their parents' relationship. Five response options were provided: friendly, cooperative, distant, lots of conflict, and don't know. The children's responses are summarised in Table 2.1.

| Inter-parental relationship | Parents had separated (%) | Parents lived together with child (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Friendly | 25.1 | 63.0 |

| Cooperative | 22.1 | 22.3 |

| Distant | 18.9 | 1.7 |

| Lots of conflict | 15.8 | 1.6 |

| Don't know | 18.1 | 11.4 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| No. of children | 714 | 2,833 |

Note: A chi-square test was used to compare response distributions between the two groups of children (χ2 (4, n = 3547) = 764.81; p < .001).

Of the children with a non-resident parent, nearly one-half (47%) described the relationship between their parents as either friendly or cooperative, with similar proportions reporting each of these options. On the other hand, 16% reported lots of conflict between their parents, 19% considered the relationship to be a distant one, and 18% expressed uncertainty. By contrast, the reports of children who were living with both (biological) parents tended to be much more positive,11 with 63% describing the relationship between their parents as friendly and 22% as cooperative; that is, 85% provided either of these two favourable assessments. Few children who were living with both parents in the same home described the inter-parental relationship as distant or marked by conflict (these alternatives were each selected by less than 2% of the children). A slightly smaller proportion of children who were living with both parents than those with separated parents indicated uncertainty about the quality of their parents' relationship with each other (11% vs 18%).

Comparison of children's and parents' perceptions of the quality of the inter-parental relationship

Before comparing children's and parents' perceptions of the quality of the inter-parental relationship, the reports of resident and non-resident parents on this issue are outlined (Table 2.2). Separated parents were asked to indicate how well they got along with their child's other parent by selecting one of the following response options: very well, well, neither well nor poorly, poorly, very poorly/badly, or that they had no contact with the other parent. In the following discussion, reports of getting along very well or well are treated as descriptions of a favourable relationship, while reports of getting along poorly or very poorly/badly are classified as descriptions of an unfavourable relationship. The selection of "neither well nor poorly" is taken to reflect a neutral stance.

Regardless of their gender and residence status, parents were more likely to report a favourable than unfavourable relationship. Table 2.2 presents the assessments of all (separated) resident mothers in the sample focused on; and of the resident mothers and non-resident fathers in the "former couples" sample (where both parents of the same children were interviewed).12 Of all resident mothers, 40% provided favourable assessments, 26% indicated a neutral stance, and 20% provided unfavourable assessments. The remainder said that they had no contact with their child's father. A similar overall pattern of assessments emerged for the resident mothers and non-resident fathers in the former couples sample: around one-half (49-54%) viewed their relationship favourably, less than one-quarter (22-23%) provided unfavourable assessments, and 20-26% saw the relationship in a neutral light. It is worth re-iterating here that parents living elsewhere who had had no contact with their child in the previous 12 months were not interviewed. Given that the former couple sample necessarily focuses exclusively on cases where both parents of the study children were interviewed, it is not surprising that few parents in this sample had no contact with each other (2-3%).

| How well resident and non-resident parents get along a | Separated resident mothers (%) | "Former couples" sample b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resident mothers c (%) | Non-resident fathers (%) | ||

| Very well | 12.3 | 15.6 | 14.7 |

| Well | 27.3 | 33.0 | 39.2 |

| Neither well nor poorly | 25.7 | 26.1 | 20.3 |

| Poorly | 9.2 | 11.2 | 12.0 |

| Very poorly/badly | 11.4 | 10.7 | 11.4 |

| No contact with other parent | 14.2 | 3.4 | 2.4 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| No. of parents | 621 | 351 | 351 |

Notes: a Resident and non-resident parents include those with shared care time. Parents who were classified as the primary carer of the study child in Wave 5 are here treated as resident parents, and parents who were classified as living elsewhere in Wave 5 are here treated as non-resident parents. No statistical test was used to compare responses of mothers and fathers of the "former couples" given that these responses were not independent. b Former couples are those where both parents of same child were interviewed. c These mothers form a subset of the "separated resident mothers" in the left-hand column.

Table 2.3 shows children's perceptions compared with their parents' perceptions of the quality of the inter-parental relationship. The upper panel of this table focuses on the reports of children and resident mothers (hereafter called "child-resident mother sample") and the lower panel outlines the reports of children and their non-resident fathers (hereafter called "child-non-resident father sample").13 The precise question and response options provided to children and their parents differed considerably, and these differences may well reduce the level of correspondence of patterns of answers between the two generations.

| Parents' reports | Children's reports | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friendly/cooperative (%) | Distant (%) | Lots of conflict (%) | Total (%) | |

| Reports of resident mothers a | ||||

| Very well/well | 36.2 | 5.6 | 1.1 | 43.0 |

| Neither | 14.1 | 7.4 | 3.2 | 24.7 |

| Very poorly/poorly | 5.1 | 5.4 | 10.1 | 20.6 |

| No contact with other parent | 3.0 | 4.7 | 4.0 | 11.7 |

| Total | 58.5 | 23.1 | 18.4 | 100.0 |

| No. of observations | 300 | 123 | 95 | 518 |

| Reports of non-resident fathers a | ||||

| Very well/well | 45.4 | 6.4 | 1.6 | 53.4 |

| Neither | 9.6 | 6.9 | 1.8 | 18.3 |

| Very poorly/poorly | 7.6 | 6.4 | 11.8 | 25.8 |

| No contact with other parent | 0.7 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 2.5 |

| Total | 63.2 | 20.2 | 16.6 | 100.0 |

| No. of observations | 194 | 67 | 50 | 311 |

Note: a Resident and non-resident parents include those in shared time; that is, parents who were interviewed as the primary carer of the study child in Wave 5 are here treated as resident parents, and parents who were interviewed as parents living elsewhere in Wave 5 are here treated as non-resident parents.

As suggested in the above-mentioned related analyses, children and their resident mothers and non-resident fathers most commonly reported favourably on the parental relationship, though children's views were generally more positive than those of their resident parents. This can be seen by comparing the "Total" results in Table 2.3, which summarise the views of the children (the rows labelled "Total") and those of their resident mothers and fathers (the "Total" column).

In relation to the child-resident mother sample, 59% of children believed that their parents had a friendly or cooperative relationship, while 43% of the mothers reported that they got along well or very well with their child's father. Similar proportions of children and their mothers provided negative descriptions: 21% of mothers reported getting along poorly or very poorly/badly with the father and 18% of children considered the inter-parental relationship to entail lots of conflict. The proportion of mothers who said that they neither got along well nor badly was similar to the proportion of children who described the inter-parental relationship as distant (25% vs 23%). Of course, a distant relationship may be interpreted quite differently from one that reflects neither getting along well nor badly. Some mothers (12%) said that they had no contact with their child's father.

Regarding the child-non-resident father sample, a higher proportion of children than fathers considered the relationship to be favourable (63% vs 53%) and a lower proportion of children than fathers considered it to be unfavourable (children 17%; fathers 26%), with the remaining one in five children and a similar proportion of fathers describing the relationship as distant. A small proportion of fathers said they had no contact with their child's mother. Again, it should be kept in mind that fathers who had not seen the child in the past year were not interviewed.

The other percentages in Table 2.3 provide insight into the proportions of parent-child pairs who provided similar or dissimilar views. For example, the top panel shows that 36% of the child-resident mother sample provided favourable assessments (i.e., the mothers reported that they got on very well or well, while their child said that relations were friendly or cooperative). In 10% of cases, both mother and child described the relationship as unfavourable, and in 7%, the mothers indicated that they neither got along well nor poorly with the father, while the children characterised the relationship as distant. In other words, 54% of children and their mothers provided similar assessments of the relationship between the separated parents and 35% of children and their mothers provided dissimilar assessments.14 Of the remaining 12%, mothers indicated no contact with the father while their children's reports were split between the three categories (friendly/cooperative, distant, lots of conflict) (with these assessments each provided by 3-5%).

The generally consistent descriptions of the quality of inter-parental relationship were also apparent when comparing the reports of children and their non-resident fathers. Specifically, 45% of those in the child-non-resident father sample provided a favourable description of the inter-parental relationship, 12% provided an unfavourable description and 7% indicated that the relationship was neither positive nor negative (the response option for fathers) or distant (the response option for children). Taken together, 64% of children and fathers provided similar assessments and 34% provided dissimilar views while the remainder represented cases where the father had no contact with the child's mother (applying to almost 3%).

Thus, both for the child-resident mother and child-non-resident father samples, the children's reports were largely consistent with those of their parents. Secondly, both children and parents most commonly considered the inter-parental relationship to be favourable.

Where children's perceptions were dissimilar to parents' own reports, children tended to provide the more positive picture. For example, in 19% of the child-resident mother sample, children described the relationship as friendly or cooperative, while their mother either indicated that the relationship was poor or that they got along neither well nor poorly. For 10% of the child-resident mother sample, the children provided a less favourable assessment of the relationship compared with their mother (i.e., where the child described the relationship as distant while their mother indicated that she and the father got along well or very well; or where the child reported much conflict and their mother provided a favourable assessment or indicated that they neither got along well nor poorly with the father).

Children's perceptions of the inter-parental relationship, by child gender, care-time arrangements, and age at separation

Children's assessments of their parents' relationship with each other did not vary significantly according to the children's gender or age at parental separation (based on four age-at-separation groups). However, the two groups of children whose parents had been separated when they were less than 5 years old (i.e., longer duration of parental separation) were less likely to describe their parents' relationship as marked by high conflict, compared with the two groups whose parents had been separated for a shorter duration (12-13% vs 20-23%) (see Table 2.4). In addition, although the children's assessments did not vary significantly with their personal reports of their living arrangements, their assessments varied according to their (more detailed) living arrangements, as reported by their parents.

| Friendly/cooperative (%) | Distant (%) | Lots of conflict (%) | Don't know (%) | Total (%) | No. of children | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender of child | ||||||

| Boys | 48.9 | 19.1 | 16.2 | 15.9 | 100.0 | 370 |

| Girls | 45.2 | 18.6 | 15.4 | 20.7 | 100.0 | 344 |

| Children's report of their own living arrangements | ||||||

| Mostly (or only) with mother | 47.9 | 19.8 | 14.2 | 18.1 | 100.0 | 508 |

| Mostly (or only) with father | 45.9 | 10.5 | 21.4 | 22.3 | 100.0 | 57 |

| Equally with both parents | 48.6 | 19.0 | 16.8 | 15.7 | 100.0 | 137 |

| Resident parents' reports of care-time arrangements | ||||||

| Father nil time in the last 12 months | 18.3 | 27.3 | 20.4 | 34.0 | 100.0 | 90 |

| Father daytime only | 53.2 | 13.8 | 9.6 | 23.4 | 100.0 | 107 |

| Father 1-13% of nights (mother 87-99%) | 58.1 | 19.4 | 13.1 | 9.4 | 100.0 | 114 |

| Father 14-34% of nights (mother 66-86%) | 53.9 | 18.7 | 14.3 | 13.0 | 100.0 | 226 |

| Shared time (35-65% of nights with each parent) | 52.8 | 19.1 | 22.8 | 5.3 | 100.0 | 86 |

| Father 66-100% (mother 0-34% of nights) | 47.8 | 12.2 | 14.2 | 25.7 | 100.0 | 63 |

| Child's age at parental separation | ||||||

| < 1 year old | 48.0 | 19.6 | 12.2 | 20.3 | 100.0 | 301 |

| 1-4 years old | 51.6 | 18.5 | 12.6 | 17.3 | 100.0 | 103 |

| 5-9 years old | 48.0 | 18.3 | 20.1 | 13.6 | 100.0 | 166 |

| 10+ years old | 39.8 | 18.7 | 22.7 | 18.7 | 100.0 | 127 |

Notes: Chi-square tests were used to compare responses of perceived inter-parental relationship by children's gender (χ2 (3, n = 714) = 2.89; p > .05 not significant); by children's own report of living arrangements (χ2 (6, n = 702) = 5.72; p > .05 not significant); by resident parents' reports of care-time arrangements (χ2 (15, n = 686) = 69.35; p < .001); and by child's age at parental separation (χ2 (9, n = 697) = 13.42; p > .05 not significant). Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Table 2.4 shows that, compared with other children, those who had not seen their father during the previous 12 months were less likely to describe the relationship between their parents as friendly or cooperative (18% vs 48-58%) and more likely to describe it as distant (27% vs 12-19%) or to express uncertainty about the quality of the relationship (34% vs 5-26%). In addition, children in two of the six living arrangements - those who had not seen their father for the last 12 months, and those who experienced shared care time - were more likely than the other children to describe the relationship as marked by conflict (20% and 23% respectively). These results are fairly consistent with those based on the reports of parents in the Longitudinal Study of Separated Families where fathers never saw their child. Both fathers and mothers who reported these circumstances were the most likely of all groups examined to describe their relationship as entailing much conflict or as fearful (Kaspiew et al., 2009).

As indicated above, one-third of children who had not seen their father in the previous 12 months said that they did not know how to describe the relationship between their parents. These children were the most likely of all children to state this. This is not surprising, given the limited opportunity they would have had to observe or read how their parents got along with each other. Around one-quarter of children who spent time with their father in the daytime only and those who spent the majority of nights (66-100%) with their father also expressed uncertainty about the quality of the relationship between their parents. Children with shared care time were least likely to express uncertainty about this matter (5%).

Children's perception of the inter-parental relationship and views about their parents' separation

Children's views on their parents' separation (outlined in section 2.4) are likely to be strongly influenced by their perceptions of how well their parents were getting along with each other. Although it is not possible to explore causal connections in the present analyses, the results depicted in Figure 2.7 suggest that these views were linked in the expected direction. The greatest contrast in patterns of views about the separation emerged for those who described the inter-parental relationship in favourable or unfavourable terms (rather than as distant).

Figure 2.7: Proportions of children who felt better, relieved or had divided loyalties about their parents' separation, by their perception of the inter-parental relationship, K cohort, Wave 5

Notes: Sample sizes: friendly/cooperative, n = 334-337; distant, n = 140-141; lots of conflict, n = 141. Confidence intervals are shown by the horizontal line extending beyond each bar. A lack of overlap in the confidence intervals for comparison groups (or slight overlap - see note a in Figure 2.2) indicates that the values are statistically significantly different at p < .05. The latter two measures represent scores on derived scales, ranging from 1.0 to 5.0. Scores of 3.5-5.0 are here taken to reflect agreement.

Children who believed that their parents' relationship entailed much conflict were more likely than those who perceived their parents' relationship as friendly or cooperative to believe that their parents' separation was better for them than the alternative (45% vs 29%). In addition, the former group of children were more likely than both of the other groups to feel relieved about the separation (with little desire for parental reconciliation) (52% vs 23-33%) and to experience divided loyalties (38% vs 15-20%).

2.6 Children's perceptions of their role in making decisions about their living arrangements

A component of the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) 2009 evaluation of the 2006 family law reforms was a survey of around 700 Australian adolescents aged 12-18 years whose parents had separated after July 2006. Drawing upon the data from this survey, Lodge and Alexander (2010) reported that 63% of the adolescent participants said that they had wanted to have a say in the decision about who they would live with and 70% of all adolescents believed they had input into this decision. Similarly, two other Australian studies (Cashmore & Parkinson, 2008; Parkinson et al., 2005) reported that at least one-half of the children studied had some say about their living and contact arrangements after parental separation.15

Similar questions were asked of the LSAC children in the K cohort with a parent living elsewhere. Specifically, children were asked: (a) Have you had a say in any of the decisions about who you would live with?; and (b) Did you want to have a say about who you would live with?

Taken together, the results in Table 2.5 show that over one-half (56%) of the children reported that they had wanted to have a say in the decision about who they would live with, and a slightly lower proportion (49%) said that they did have a say on their living arrangements. One-fifth did not want to provide input (20%), while a higher proportion (28%) believed that they did not have a say. Just under one-quarter (24%) were unsure whether they had wanted to have a say, and a similar proportion (23%) did not know whether they actually had a say. Taken separately, of those with a view on whether they wanted a say (other than uncertainty), 73% answered in the affirmative, and of those with a view on whether they did have say, 64% reported that they had done so - proportions that are similar to those reported by Lodge and Alexander (2010; based on a sample that included older adolescents).

| Did you want to have a say about who you would live with? | Have you had a say in any of the decisions about who you would live with? | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (%) | No (%) | Don't know (%) | Total (%) | |

| Yes | 39.4 | 12.0 | 4.5 | 55.9 |

| No | 5.3 | 10.1 | 4.9 | 20.3 |

| Don't know | 4.7 | 5.6 | 13.5 | 23.8 |

| Total | 49.4 | 27.8 | 22.8 | 100.0 |

| No. of children | 356 | 202 | 158 | 716 |

Table 2.5 also shows that: around four in ten children (39%) both wanted to have and believed they did have a say (the most common of all nine scenarios); 12% wanted to have but felt they had not had a say; 10% neither wanted to have nor believed they did have a say; and 5% said that they did have a say, despite not wanting to do so. However, the second most common scenario, applying to one-third of the children, was that children were unsure about one or both of these issues.

Children's views about having input into care-time arrangements, by child gender, type of arrangement, and age at separation

For succinctness, this section focuses exclusively on factors relating to whether children reported that they wanted a say in their living arrangements and whether they believed that they did have a say. Table 2.6 shows the proportion of children who responded affirmatively to each question according to their gender, living arrangements and age at parental separation. The analyses were run separately for both issues: desire to have a say and beliefs about doing so.

| Selected characteristics | Wanted to have a say (%) | Had a say (%) | No. of children |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender of child | ns | ns | |

| Boys | 54.5 | 51.1 | 371 |

| Girls | 57.4 | 47.6 | 346 |

| Children's report of their own living arrangements | * | ** | |

| Mostly (or only) with mother | 53.8 | 46.4 | 511 |

| Mostly (or only) with father | 72.3 | 71.6 | 57 |

| Equally with both parents | 54.2 | 51.6 | 137 |

| Care-time arrangements, resident parents' reports | * | *** | |

| Father nil time in the last 12 months | 55.8 | 48.8 | 91 |

| Father daytime only | 53.3 | 46.6 | 107 |

| Father 1-13% of nights (mother 87-99%) | 55.0 | 44.8 | 114 |

| Father 14-34% of nights (mother 66-86%) | 51.3 | 44.5 | 227 |

| Shared time (35-65% of nights with each parent) | 66.7 | 58.2 | 86 |

| Father 66-100% of nights (mother 0-34% of nights) | 68.1 | 69.0 | 63 |

| Child's age at parental separation | ns | ns | |

| < 1 year | 54.8 | 49.7 | 303 |

| 1-4 years | 47.8 | 41.4 | 103 |

| 5-9 years | 60.0 | 53.2 | 167 |

| 10+ years | 60.2 | 53.9 | 127 |

Note: Chi-square tests were used to assess the relationship between each issue taken separately (whether wanted a say and whether did have a say) and each variable (e.g., children's gender). * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001; ns = not significant).

It should be noted that many children of separated families experience a change in living arrangements during the years following separation (see Qu & Weston, 2014). Children's desire to have an input into their living arrangements and any opportunities for having an input may have occurred during the separation period and/or months or years later, with the desire and opportunity not necessarily occurring during the same period.

Neither the desire to have input into these decisions, nor the belief that they had done so, varied significantly according to the children's gender or age at the time their parents had separated. Both issues about having a say were linked with their care-time arrangements. Compared with children who either reported that they lived equally with both parents or mostly or only with their mother, those who reported that they mostly or only lived with their father were more likely to have indicated that they had wanted a say in the decision and that they had done so. Specifically, 72% of those who said they spent most or all nights with their father wanted a say and 72% believed that they did have a say; 54% of those reporting other arrangements indicated that they had wanted a say and 46-52% reporting such arrangements said that they did have a say.

A mostly similar pattern of results emerged when the children's living arrangements were based on the resident parents' reports. Compared with children who, according to their resident parent, spent most or all nights with their mother, those in the care of their father for most or all nights were more likely to indicate that they had wanted a say (68% vs 51-56%) and to indicate that they did have a say (69% vs 45-49%). However, those with shared care time were also more likely than those who spent most or all nights with their mother to indicate that they had wanted a say (67% vs 51-56%) and to report that they did have a say (58% vs 45-49%). These results relating to shared care time differ from those based on children's reports of their living arrangements: the proportions of children wanting and having a say did not vary significantly according to whether they said that they lived mostly or only with their mother or equally with each parent.

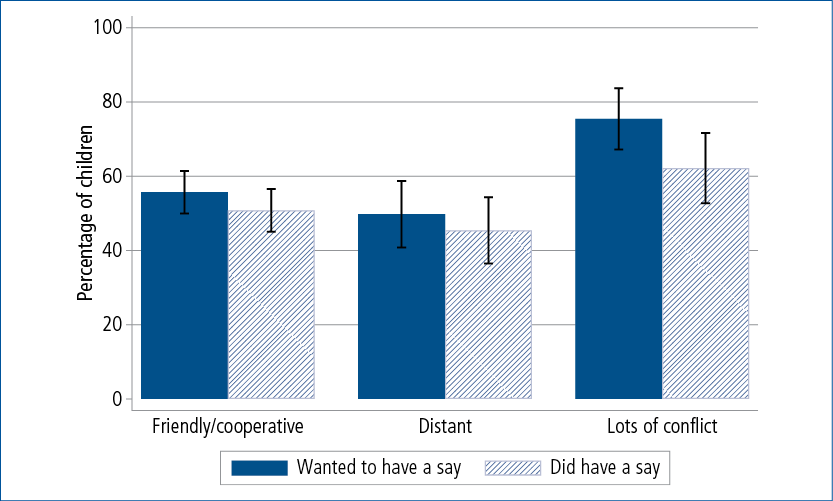

Children's perception of the quality of the inter-parental relationship and their role in making decisions about their living arrangements

Children's desire to participate in decisions about their living arrangements and their beliefs about their actual participation were associated with their perceptions of the quality of their parents' relationship, as shown in Figure 2.8. Children who described their parents' relationship as marked by conflict were more likely than those who said that their parents had a distant or friendly/cooperative relationship to report that they had wanted to have a say (75% vs 50-57%) and to indicate that they did have a say (62% vs 45-51%). This result is consistent with the finding from Parkinson et al. (2005) that young people who reported many arguments between their parents were more likely to have had some say compared with those who reported few or no arguments between their parents. This theme also emerged in the qualitative study by Cashmore and Parkinson (2008). Section 2.5 of this chapter showed that children who considered their parents' relationship to entail much conflict were also more likely than other children to report feeling "caught" between parents in the sense of finding it difficult to talk to one parent about the other and to be fair to both parents. Possibly, negative inter-parental relationships and feeling caught between their parents increased the likelihood of children wanting to have a say about their living arrangements (or changing their living arrangements).

Figure 2.8: Proportions of children who wanted to or did have a say about their living arrangements, by perceived quality of inter-parental relationship, K cohort, Wave 5

Notes: Sample sizes: friendly/cooperative, n = 337; distant, n = 141; lots of conflict, n = 115. Confidence intervals are shown by the vertical line extending beyond each bar. A lack of overlap in the confidence intervals for comparison groups (or slight overlap - see note a in Figure 2.2) indicates that the values are statistically significantly different at p < .05.

2.7 Children's views about the time spent with their non-resident parent

In Wave 5 of LSAC, the K cohort children were asked whether they were able to see their non-resident parent when they wanted to, by selecting from the response options: always, sometimes, occasionally, never, and "I don't want to see him/her". This was followed by a question about whether they thought the amount of time they spent with this parent was: nowhere near enough, not quite enough, about right, a little too much, or way too much.

Table 2.7 summarises children's responses according to the gender of their non-resident parent. The most common response to the question about whether they were able to see their non-resident parent when they wanted to was "always" (36%), followed by "sometimes" (24%) and "occasionally" (22%). The least common was "never" (8%). It is worth noting that 10% of children said that they did not want to see this parent at all. The patterns of children's responses were broadly similar whether it was their mother or their father who lived elsewhere.

Regarding their views on the overall amount of time they spent with their non-resident parent, the most common response was that the amount of time was "about right" (44%), followed by "not quite enough" (30%) and "nowhere near enough" (21%). That is, one-half of the children did not feel that they had sufficient time with their non-resident parent. Only small proportions of children reported that they spent "a little too much" or "way too much" time with this parent (6% combined). Again, children's views on this issue did not vary significantly according to which of their parents lived elsewhere.

| Responses | Gender of non-resident parent | All non-resident parents (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Father (%) | Mother (%) | ||

| Whether able to see non-resident parent when wanted | |||

| Always | 35.9 | 39.2 | 36.2 |

| Sometimes | 22.4 | 33.4 | 23.5 |

| Occasionally | 23.0 | 16.2 | 22.4 |

| Never | 8.1 | 5.7 | 7.9 |

| I don't want to see him/her | 10.6 | 5.6 | 10.1 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| No. of children | 650 | 67 | 717 |

| Whether amount of time spent with non-resident parent was enough | |||

| Nowhere near enough | 21.2 | 19.1 | 21.0 |

| Not quite enough | 29.1 | 33.1 | 29.5 |

| About right | 43.9 | 43.0 | 43.8 |

| A little too much | 3.7 | 1.1 | 3.4 |

| Way too much | 2.1 | 3.8 | 2.3 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| No. of children | 645 | 67 | 712 |

Notes: Based on chi-square tests, there is no statistically significant association between children's reports on these two issues (taken separately) and the gender of non-resident parents. Percentages may not total 100.0% exactly due to rounding.

Children's views about the time spent with their non-resident father and ability to see him when they wished

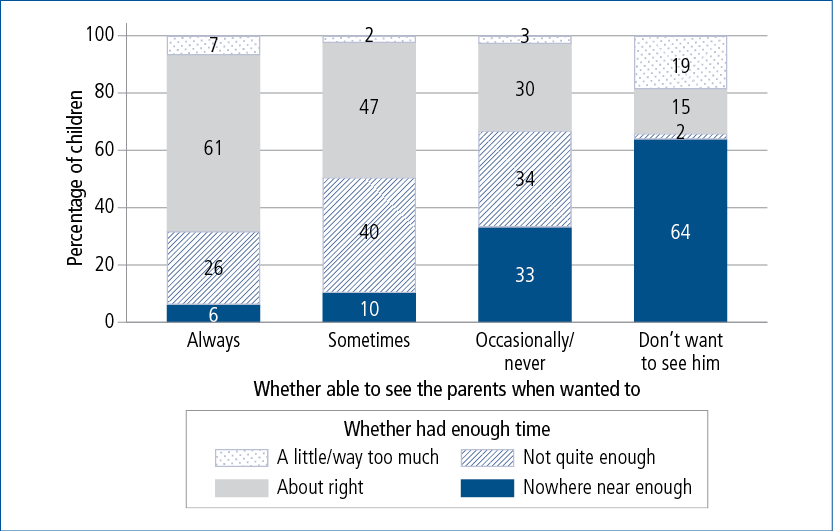

Not surprisingly, Figure 2.9 shows that where the children's fathers lived elsewhere from the primary carer (the most common arrangement after parental separation), children's views on the amount of time they spent with him varied significantly according to whether they were able to see their father when they wished.16 However, some of the results may at first seem counter-intuitive. Nearly two-thirds of the children who did not want to see their father at all reported that the amount of time spent with him was nowhere near enough, compared with 6-33% of other children. Further analysis reveals that most of the children (nearly two-thirds) who did not want to see their father had not seen him in the previous 12 months (and the remaining one-third either saw him during the daytime only or spent 1-13% of nights with him). Many of the children who neither wanted to see their father nor had seen him in the previous 12 months may have considered it nonetheless obvious their time spent with their father must be far from adequate.

Figure 2.9: Children's reports about the time spent with their non-resident father, by whether they were able to see him when they wanted to, K cohort, Wave 5

Note: Sample sizes: always, n = 232; sometimes, n = 151; occasionally/never, n = 201; don't want to see him, n = 61.

Figure 2.9 shows that most of the children who felt that they were always able to see their father when they wished reported that their time with their father was about right (61%). Such a judgement was also reported by 47% of children who felt they were sometimes able to see their father when they wanted to, and by 30% of those who said that they were never or only occasionally able to see their father when they wished. Similar proportions of children who were sometimes able to see their father when they wanted to judged their time with him to be not quite enough or about right (40% and 47% respectively). In addition, much the same proportions of children who felt that they were never, or only occasionally, able to see their father when they wished judged their time with their father to be nowhere near enough, not quite enough or about right.

Whereas one in five children who did not want to see their father said that their time with him was a little or way too much, only 2-7% of children in the other three groups judged their time with their father to be excessive.

Children's views about the time spent with their non-resident father by child gender, care-time arrangements, and age at separation

Table 2.8 presents the proportions of children who believed that they were always able to see their non-resident father when they wished and the proportions of children who reported having nowhere near enough time with him, according to selected characteristics.

A higher proportion of girls than boys reported that they were always able to see their father when they wanted to (42% vs 30%), but similar proportions (20-23%) reported that the amount of time with him was nowhere near enough.

It is not surprising that children's ability to see their father when they wished and the belief that they had nowhere near enough time with him were linked with their care-time arrangements, as reported by the children themselves and by their resident mothers (including those with shared time). Compared with children who said that they were living equally with both parents, those who said that they were mostly or only living with their mother were less likely to indicate that they were always able to see their father when they wanted to (32% vs 52%) and more likely to say that they had nowhere near enough time with him (24% vs 10%).

| Selected characteristics | Always able to see father (%) | Nowhere near enough time with father (%) | No. of children a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender of child | ** | ns | |

| Boys | 30.3 | 20.1 | 334 |

| Girls | 42.1 | 22.8 | 317 |

| Children's report of their own living arrangements | *** | *** | |

| Mostly (or only) with mum | 32.0 | 24.1 | 509 |

| Equally with both parents | 51.9 | 9.6 | 123 |

| Care-time arrangements, resident parents' reports | *** | ** | |

| Father nil time in the last 12 months | 7.5 | 60.6 | 92 |

| Father daytime only | 38.0 | 19.5 | 107 |

| Father 1-13% of nights (mother 87-99%) | 29.0 | 18.5 | 114 |

| Father 14-34% of nights (mother 66-86%) | 45.9 | 10.5 | 226 |

| Shared time | 59.8 | 3.3 | 69 |

| Child's age at parental separation | ns | * | |

| < 1 year | 32.2 | 26.5 | 287 |

| 1-4 years | 41.6 | 20.3 | 88 |

| 5-9 years | 35.4 | 16.7 | 150 |

| 10+ years | 43.2 | 12.6 | 112 |

Notes: a No. of children refers to the sample sizes for the column "Always able to see father". Chi-square tests were used to identify the strength of associations between each variable (e.g., children's gender) and children's views on: (a) whether they were always able to see father; and (b) whether they had nowhere near enough time with him. * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001; ns = not significant.

The link between views on these two issues and care-time arrangements was even more apparent when the more detailed measure of care-time arrangements (i.e., those reported by the mothers) were focused on. Children in shared time were the most likely of all care-time groups to report that they were always able to see their father when they wanted to (60%), and the least likely to say that they spent nowhere near enough time with him (3%). In addition, children who spent 14-34% of nights with their father (the arrangement in Table 2.8 that was closest to shared care time) were the second most likely to report that they were always able to see their father on time (46%), and the second least likely to believe that they spent nowhere near enough time with him (11%).

On the other hand, those who had not seen their father within the previous 12 months were the least likely to report that they were always able to see their father when they so wished (8%) and the most likely to report that they spent nowhere near enough time with him (61%).

Further analysis indicated that a large proportion of children who had not seen their father within the previous 12 months said that they did not want to see him (45%) and a similar proportion (43%) reported being occasionally or never able to see him when they wanted to. (These results are not presented in Table 2.8.)

Children's views on whether they were able to see their father when they wished did not vary significantly according to the child's age at separation. Nevertheless, children who were younger when their parents had separated were more likely to say that the amount of time with him was nowhere near enough. However, these differences disappeared once parents' reports on the children's care-time arrangements were controlled (results not shown here).

Children's views about the time spent with their non-resident father and their perceptions of the inter-parental relationship

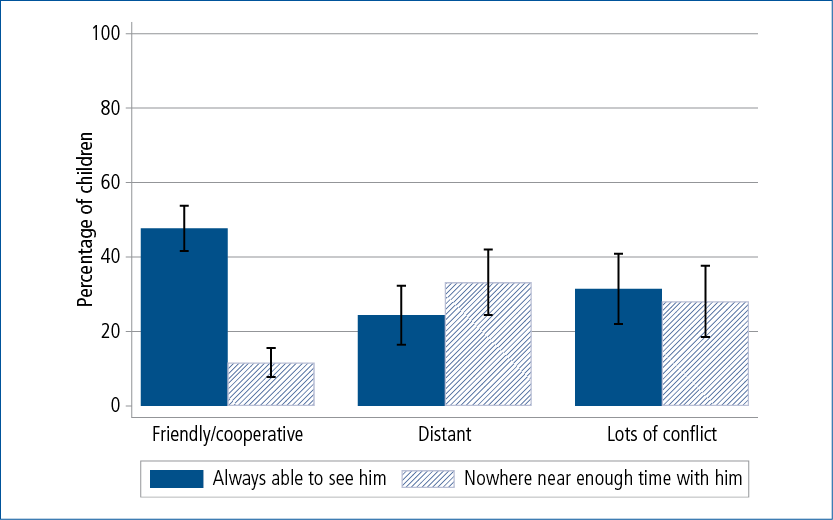

As expected, children's views on whether they were always able to see their father when they wished and whether they had enough time with him varied with their perceptions of the quality of their parents' relationship. Figure 2.10 shows that those who described their parents' relationship as friendly or cooperative were more likely than others to feel that they were always able to see their father when they wanted to (48% vs 24-31%) and thus, unsurprisingly, less likely to feel that they spent nowhere near enough time with him (12% vs 28-33%).17

It is worth noting, however, that nearly one-fifth of the children who described their parents' relationship as entailing a great deal of conflict said that they did not want to see their father, compared with one-tenth of children who described the inter-parental relationship as distant, and even fewer (2%) who considered the relationship to be friendly or cooperative (results not shown in Figure 2.10).

Figure 2.10: Proportions of children who reported they were able to see their non-resident father always or not enough, by perceived quality of inter-parental relationship, K cohort, Wave 5

Notes: Sample sizes: friendly/cooperative, n = 304; distant,n = 132; lots of conflict, n = 104. Confidence intervals are shown by the vertical line extending beyond each bar. A lack of overlap in the confidence intervals for comparison groups (or slight overlap - see note a in Figure 2.2) indicates that the differences in values are statistically significant at p < .05.

2.8 Summary

There is a growing recognition of the importance of seeking children's perspectives on matters that concern them. Parents' interpretations of their children's understanding of the separation and feelings about it do not necessarily correspond with children's accounts. This chapter focuses almost exclusively on the perspectives of children whose parents were separated. It examines: (a) their feelings about parental separation; (b) their interpretation of the quality of the relationship between their parents; (c) their preferences and perceived opportunities regarding having a say in their living arrangements; and (d) their views about the time they spent with their non-resident parent.18

Children's feelings about parental separation

Overall, children were more likely to disagree than agree with the statements that they: felt relieved that their parents had separated, wished their parents would get back together, felt split or torn between their parents, or felt that they could not talk about one parent to the other. On the other hand, they were more likely to agree than disagree with the statement that they found it hard to be fair to both parents.

Nevertheless, substantial minorities of children provided the alternative views to those outlined above. For example, around one in five children indicated that their parents' separation provided them with a sense of relief, and more than one in four wished their parents would get back together.

An additional question sought children's views on whether their parents' separation was better for them or whether they would have been better off had their parents stayed together. The children were nearly twice as likely to indicate that the separation was better for them than to say that they would have been better off had their parents stayed together. However, nearly one-half gave a neutral response, indicating that they neither agreed or disagreed that they would have been better off. The high uncertainty rate about this issue (expressed by two in five children) is not surprising given that the parents of many of the children in this sample had separated when the children were very young.

In general, however, views about parental separation did not vary significantly with children's age at parental separation or gender. Nevertheless, girls were more likely than boys to feel relieved about their parents' separation (with little if any desire for their parents to get back together). There were also no clear and consistent associations between children's views about parental separation and their care-time arrangements, where they spent at least some time with their father. Those who had not seen their father in the previous 12 months were the most likely to indicate feeling relieved, and with little if any wish for their parents to get back together.

In many cases where relief about parental separation was expressed, such relief may have resulted from the child being removed from everyday family dynamics that were highly dysfunctional. Subsequent analysis indicated that the children who had not seen their father within the previous 12 months tended to provide less favourable views about the quality of their parents' relationship than other children.19

Children's perceptions of the inter-parental relationship

While the LSAC children with separated parents most commonly provided a positive picture of their parents' relationship (nearly one-half reported that their parents had a friendly or cooperative relationship), their reports were much less likely to be positive than those provided by LSAC children whose parents had not separated.

The analyses also compared children's perceptions of the quality of their parents' relationship with their parents' own reports. Children's perceptions were more often similar to, than different from, those of their parents, and where differences emerged, children tended to provide the more positive picture. Possibly, some children were not as astute as others about their parents' relationship dynamics, or some parents who were not getting along very well were able to hide this from their children.

Children's views about their parents' separation are likely to be strongly influenced by any recollections they have about their pre-separation home environments and by their perceptions of their post-separation circumstances, including their views about the quality of their parents' relationship. Indeed, children who described their parents' current relationship as being marked by considerable conflict were more likely than other children to feel that they were "caught" between their parents.

Children's perceptions of their role in making decisions about their living arrangements

Over one-half of all children reported that they had wanted to have a say in the decision about who they would live with, and the remainder were evenly split between not wanting to have a say and being unsure. In addition, nearly one-half reported that they did have a say on their living arrangements. These findings were similar to those of some previous Australian studies (Cashmore & Parkinson, 2008; Lodge & Alexander, 2010; Parkinson et al., 2005). Children who spent the majority of nights with their father were the most likely, or among the most likely, to indicate that they wanted a say and that they did have a say in their living arrangements. In addition, children who described their parents' relationship as entailing a great deal of conflict were more likely than other children to have wanted to have a say and to believe that they had done so. This link between children's views about having a say and the quality of inter-parental relationship is consistent with previous research (Cashmore & Parkinson, 2008; Parkinson et al., 2005). While it is possible that many of these children wanted to have a say so that they could avoid witnessing acrimonious conflict between their parents, Cashmore and Parkinson (2008) found that compared to other children, those whose parents had a problematic relationship with each other, such as high conflict or violence, were less concerned that voicing their views would put them in a difficult position. Cashmore and Parkinson also found that children wanted it to be acknowledged that such issues concerned their lives and that they should therefore be able to make some contribution to the decision-making process.

Children's views about the time spent with their non-resident parent

This chapter also explored children's views about the amount of time they spent with their non-resident parent and whether they were able to see this parent when they wished. Over one-third of children said that they were always able to see their non-resident parent when they wished, while nearly one in ten said they were never able to do so, and one in ten said that they did not want to see this parent.

One-half of the children said that the amount of time with their non-resident parent was either nowhere near enough or not quite enough. The remainder mostly indicated that the amount of time with their non-resident parent was about right. Few children described this time as a little too much or way too much. Unsurprisingly, the majority of children who had not seen their father within the previous 12 months felt that they had nowhere near enough time with him.

Children's preferences on this issue were related in ways that could be expected to their perceptions of the quality of their parents' relationship. Compared with those who described this relationship as distant or marked by conflict, children who considered the relationship to be friendly or cooperative were more likely to say that they could always see their father when they wanted to and were thus less likely to indicate that they spent nowhere near enough time with him. Similarly, Parkinson and colleagues (2005) also found that compared with other children, those whose parents argued a great deal were more likely to indicate that they were not able to see their non-resident parents when they wanted to.

Data limitations

The results in this chapter should be interpreted with some caution given limitations inherent in the data. Firstly, some children with a parent living elsewhere did not complete the questions on parental separation. These children were more likely than those who answered the questions to have not seen their father in the previous 12 months20 and to have either experienced parental separation when they were very young or never lived together with both parents. Secondly, non-resident parents who spent no face-to-face time with their study child were not interviewed, and were therefore not represented in the analyses of parents' reports.

Final comments

This chapter shows that children's views about parental separation are diverse. Consistent with prior research, the results suggest that the children (in this case aged 12-13 years) tended to be aware about their parents' relationship and were able to report on how they felt about their parents' separation. Most also wanted to have a say in their living arrangements, almost half believed that they did have a say (regardless of whether they wanted it), and around two in five both wanted a say and believed that they had been given this opportunity.

Children's views about their parents' separation, their perceptions of the quality of their parents' relationship, and their views about having a say in decisions on their living arrangements were linked with each other in some ways. Home environments before parental separation were likely to have been unpleasant for many of the children. However, life after parental separation did not appear to be easy for some in terms of relationship dynamics among both the parents and children. Some parents themselves described their inter-parental relationship unfavourably. It is not surprising, then, that a substantial minority of children felt "caught" between their parents or had divided loyalties, which was especially likely when they described their parents' relationship as entailing a great deal of conflict.

These findings are a reminder to separated parents of the difficulties their children can face when the parents themselves remain locked in acrimonious conflict. The encouragement of parents to put aside their conflict and focus on their children was one of the key aims of the 2006 family law reforms. Indeed, the results reinforce the importance of two of the central aims of the reforms: to help build strong healthy relationships and prevent separation, and to help separated parents agree on what is best for their children (rather than litigating). To be consistent with Article 12 of the Convention of the Rights of the Child, the process in reaching such agreement should ensure that the right of children to freely express their views on matters that affect them is upheld and that such views are taken into account.

2.9 References

Achenbach, T. M., McConaughy, S. H., & Howell, C. T. (1987). Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin, 101(2), 213-232.

Baxter, J. A., Weston, R., & Qu, L. (2011). Family structure, co-parental relationship quality, post-separation paternal involvement and children's emotional wellbeing. Journal of Family Studies, 17(2), 86-109.

Campo, M., Fehlberg, M., Millward, C., & Carson, R. (2012). Shared parenting time in Australia: Exploring children's views. Journal of Social Welfare & Family Law, 34(3), 295-313.

Campbell, A. (2008). The right to be heard: Australian children's views about their involvement in decision-making following parental separation. Child Care in Practice, 14(3), 237-255.

Cashmore, J., & Parkinson, P. (2008). Children's and parents' perceptions on children's participation in decision making after parental separation and divorce. Family Court Review, 46(1), 91-104.

Cremeens, J., Eiser, C., & Blades, M. (2007). A qualitative investigation of school-aged children's answers to items from a generic quality of life measure. Child: Care, Health & Development, 33(1), 83-89.