4. Parental influences on adolescents' alcohol use

4. Parental influences on adolescents' alcohol use

Jacqueline Homel and Diana Warren

4.1 Introduction

Alcohol has a complex role in Australian society. While most Australian adults drink alcohol at levels that cause few adverse effects, a substantial proportion drink at levels that increase their risk of alcohol-related harm (National Health and Medical Research Council [NHMRC], 2009). In many countries, including Australia, alcohol is responsible for a considerable burden of death, disease and injury; and alcohol-related harm is not limited to drinkers but also affects families, bystanders and the broader community (NHMRC, 2009; Room et al., 2010).

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study suggests that the burden attributable to substance use increases substantially in adolescence and young adulthood (Degenhardt, Stockings, Patton, Hall, & Lynskey, 2016).1 Alcohol use during early adolescence is a major risk factor for later alcohol abuse and dependence (Hingson & Zha, 2009). Alcohol can also have short-term consequences for adolescents such as injury, violence, self-harm and risky sexual behaviour (Hall et al., 2016). Excessive drinking may also have lasting effects on adolescent brain development (Jacobus & Tapert, 2013). Therefore, research that improves our understanding of the risk factors for adolescent drinking is needed to inform policy aimed at improving the health and social outcomes for young Australians.

Adolescent drinking and the family environment

For most children, the family environment is the earliest source of alcohol exposure. Alcohol is part of many family and community celebrations and cultural events. In Australia, most parents drink alcohol at least occasionally, and over 20% drink heavily (Maloney, Hutchinson, Burns, & Mattick, 2010). Most investigations show a positive association between adolescents' use of alcohol and their parents' drinking behaviour.

Early drinking behaviours such as alcohol initiation (i.e. the first drink) may be largely influenced by environmental factors, including parental drinking, attitudes and supervision practices (Richmond-Rakerd, Slutske, Heath, & Martin, 2014). Social learning theories suggest that children learn about alcohol, how it is used and its effects by observing their parents drink and hearing their parents talk about drinking. Finally, parental drinking may be associated with less effective monitoring of adolescents' activities, which may, in turn, increase the likelihood that adolescents can access opportunities to use alcohol (Dishion, Capaldi, & Yoerger, 1999; Tildesley & Andrews, 2008; King & Chassin, 2004).

The vast majority of Australian children and adolescents are exposed to drinking situations, either at home or in other social settings. A recent poll of Australians found that 79% of drinkers with children under 18 years living in their home reported consuming alcohol around their children (Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education, 2013). Social learning theory would suggest that adolescents engage in behaviour modelled by their parents. Despite Australia's legislative requirements regarding the purchase of alcohol (restricted to those aged 18 or over; with laws specifically targeting the purchase of alcohol by an adult for a minor), parents are a common source of alcohol for young adolescents. For many, drinking initiation occurs at a family event (Hearst, Fulkerson, Malonado-Molina, Perry, & Komro, 2007; Gilligan & Cypri, 2012). Research suggests that parent drinking is associated with adolescent drinking, independent of a range of other socio-demographic risk factors for early alcohol use (van der Vorst, Engels, Meeus, Dekovic, & van Leeuwe, 2005). A few Australian studies have demonstrated this association (Alati et al., 2014; Kelly et al., 2011; Mattick et al., 2015), although none have had access to reports of drinking by both parents over time.

One explanation for the association between parents' drinking and adolescents' alcohol use rests with genetics. Studies of alcohol use among children of alcoholics clearly show that the symptoms of alcohol dependence tend to cluster in families. However, these studies focus mainly on alcohol use in adulthood (Latendresse et al., 2008; McGue, Malone, Keyes & Iacono, 2014). Studies of adolescent alcohol use suggest that genetic influences on drinking behaviour in early adolescence are quite small, becoming more pronounced in later adolescence and adulthood.2

Gaps in the existing literature

Despite generally positive correlations between parental drinking and adolescent drinking, a number of important questions about this association remain. One gap in the literature is knowledge about the nature of drinking among parents of young adolescents. Most longitudinal studies of parental drinking in relation to adolescent drinking include self-reported drinking from the child's mother. If information about the father's drinking is available, it is usually reported by the mother and, in most cases, these reports are averaged across parents for analysis (e.g., Cortes, Fleming, Mason, & Catalano, 2009; Fergusson, Horwood, & Lynskey, 1995; Harrington-Cleveland & Wiebe, 2003; Peterson, Hawkins, Abbott, & Catalano, 1994; Tyler, Stone, & Bersani, 2006). This is common practice even in studies where self-reported drinking from both parents was available (e.g., Donovan & Molina, 2011; Duncan, Duncan, & Strycker, 2006; Duncan, Gau, Duncan, & Strycker, 2011; Latendresse et al., 2008).

For these reasons, the literature is unclear with regards to the role fathers' drinking plays, the relative importance of mothers' and fathers' drinking, and the extent to which parents' drinking has additive or interactive effects for adolescents' drinking. Some studies have found that the drinking of both parents predicts adolescent drinking (Alati et al., 2014; van der Zwaluw et al., 2008; Vermeulen-Smit et al., 2012) while others have found only maternal drinking to be uniquely associated with adolescent drinking (Coffelt et al., 2006; Kelly, Chan et al., 2016). None have examined the potential contribution of alcohol use in separated families by non-resident parents or where parents share care and the young person regularly spends time across two households (where there may or may not be other co-resident adults).

Whether the importance of the role of a mother's or father's drinking varies depending on the gender of the adolescent (Coffelt et al., 2006) is also unclear. While some studies have found no observed associations between parents' drinking and their children's alcohol use (e.g. Kelly, Chan et al., 2016), others (e.g., Hung, Chang, Luh, Wu, & Yen, 2015) have found that the influences of fathers' and mothers' drinking on the drinking behaviour of children differed depending on the child's gender.

Moreover, the results were rarely reported in a way that could be interpreted using concrete levels of parental drinking such as number of drinks per week. This is important because policy-makers and those who design interventions would be interested in knowing whether parental drinking that falls within recommended guidelines increases the risk for adolescent drinking, or whether the risk is mainly found in parental drinking that exceeds the guidelines. This information is also likely to be of interest to parents of adolescents. In the UK, Kelly, Chan et al. (2016) found that both light and heavy maternal drinking (compared to no drinking) increased the odds of drinking in 11 year olds. Dutch adolescents drank more between the ages of 12 and 15 if either parent drank heavily at least once a week, but were not at increased risk if their parents drank at lower levels (Vermeulen-Smit et al., 2012). Comparable evidence does not presently exist for Australian adolescents.

Another important issue is the role of parental monitoring. More monitoring of adolescents' behaviour and rule setting are consistently associated with less adolescent drinking (Peterson et al., 1994; Thompson, Roemer, & Leadbeater, 2015; Hayes et al., 2004). Some studies further suggest that parental drinking limits parents' capacities to monitor adolescents effectively (Dishion et al., 1999; Tildesley & Andrews, 2008; King & Chassin, 2004) but this aspect of the relationship between family environment and adolescent drinking has been less thoroughly explored. It is also unclear whether monitoring is always protective if adolescents are exposed to regular drinking at home. As drinking early in adolescence is a potent risk factor for later alcohol abuse as well as other problematic outcomes such as antisocial behaviour (Jackson, Barnett, Colby, & Rogers, 2015; Bonomo, Bowes, Coffey, Carlin, & Patton, 2014), it is important to examine the connections between adolescent drinking, parental drinking and parental monitoring.

In this chapter we examine linkages between parents' drinking and the drinking of their 14-15 year old children. The first aim of this chapter is to document the relationship between parental drinking and early adolescent drinking, exploring how this differs by the gender of the parents and the adolescent. The second aim is to examine the role of parental monitoring in the relationship between parental drinking and adolescent drinking. We address the following research questions:

- What are the levels of drinking among mothers and fathers of young adolescents?

- What are the levels of drinking among 14-15 year old adolescents, and what are the characteristics of those who drink alcohol?

- How do different levels of mothers' and fathers' drinking, (separately and in combination) relate to the probability of adolescent drinking, and does this vary by the gender of the parent(s) and/or the gender of the adolescent?

- Do mothers' and fathers' drinking (separately and in combination) predict a higher likelihood of adolescent drinking after controlling for socio-demographic risk factors?

- Does poorer parental monitoring explain relationships between parental drinking and adolescent drinking?

This chapter uses contemporary, nationally representative data to address some of the limitations identified earlier. We examine self-reported drinking from both parents, and we consider differences for girls and boys. We use information about the quantity and frequency of parents' drinking to examine different levels of alcohol use with reference to the NHMRC drinking guidelines. In describing the association between parental drinking and adolescent drinking, we control for a number of potentially confounding variables.

The chapter will first explore the levels of alcohol consumption among parents of adolescents. We then describe the levels of alcohol consumption of young adolescents; and how child and family characteristics are associated with the likelihood of adolescents having had an alcoholic drink. The association between adolescents' alcohol consumption at age 14-15 and their parents' alcohol consumption two years before is then described, with separate analysis for mothers and fathers in the primary household; and fathers who were not living in the primary household.3 Multivariate analysis is then used to examine the influence of parents' risky drinking, after controlling for socio-demographic characteristics. Finally, we examine the role of parental monitoring in explaining the relationship between parental drinking and adolescent drinking.

4.2 Data and methodology

This chapter uses data from the LSAC K cohort. We focus on the relationship between parental drinking at Wave 5 (when children were aged 12-13) and the study child's drinking at Wave 6 (age 14-15).4 For study children, we examine whether the child reported having had an alcoholic drink in the last 12 months, and in the last 4 weeks.5 Information about the study child's alcohol use was collected through the audio-computer-assisted interview. This method allows sensitive content to be answered by the child in total anonymity.

For information on parents' drinking, we firstly use information collected from parents in the study child's primary household; that is, the household in which they are enumerated for LSAC.6 Also, if children have parents who live apart, the parent living elsewhere is invited to participate in LSAC if they have some contact with the study child. We therefore have additional information about parents living outside the study child's primary household. However, the sample of parents living elsewhere is not representative of all separated parents, being biased toward parents who are more involved in their children's lives (Baxter, Edwards, & Maguire, 2012).

The sample used for this analysis is restricted to children with self-reported alcohol consumption data in Wave 6, whose primary caregiver was interviewed in Wave 5. It is important to note that there is a considerable amount of missing information about parents' alcohol consumption, particularly for parents who do not reside in the primary household. For this reason, and because the focus of this chapter is on the alcohol consumption of the study child, indicators of missing data for a parent's alcohol consumption are included in this analysis. Table 4.1 provides a summary of the percentage of adolescents aged 14-15 in the Wave 6 LSAC sample for whom information about parents' alcohol consumption was available.

Notes: a This category includes non-resident parents who completed the Parent Living Elsewhere (PLE) questionnaire but skipped the questions about alcohol, those who did not complete the PLE questionnaire and those who have no contact with the study child and therefore were not given the opportunity to complete the PLE questionnaire. Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 5 and 6

Our measures of parents' alcohol consumption levels are based on the NHMRC (2009) Australian guidelines and calculated based on reports of parents' usual frequency and quantity of alcohol consumption.7 Four measures of parental drinking were created:

- long-term risk: usually have more than two drinks on any day, regardless of frequency;

- short-term risk: five or more drinks on any occasion, at any time in the last year;

- regular short-term risk: five or more drinks on any occasion, at least twice a month;8 and

- level of frequent drinking: this measure differentiates between frequent drinkers who drink within the guideline for long-term risk and frequent drinkers who exceed the guideline for long-term risk. There are three categories:

- people who drink less than four days per week;

- people who drink four or more days per week, 1-2 drinks per day on average; and

- people who drink four or more days per week and drink three or more drinks per day on average.

We derived these measures for mothers and fathers in the primary household and, where applicable, for parents living elsewhere. For all parents, the variables measuring alcohol consumption include an additional category for "No information available", either because the parent did not answer the questions about their alcohol consumption or did not complete the questionnaire at all.

Most of the analyses are descriptive, documenting levels of drinking among both parents and adolescents, and how these overlap. Across all analyses, we compare outcomes for male and female adolescents. As much as is practical, we also compare influences from mothers and fathers. Multivariate logistic regression is used to examine whether parental drinking predicts adolescents drinking.

In considering the relationship between parental and adolescent drinking, it is important to control for risk factors that are associated with both, and which may confound the relationship between the two. In this study we control for:

- a family history of alcohol problems in the parents' families. In this case, we look at the study children's grandparents.

- parents' socio-economic position, which has an unclear association with drinking. Some studies suggest that while adolescents and adults of higher socio-economic positions are more likely to drink alcohol, the risk of harm is higher among those of lower socio-economic positions (Giskes, Turrell, Bentley, & Kavanagh, 2011; Melotti et al., 2011).

- whether the adolescent speaks a language other than English at home and the mother's country of birth. Both adolescent and adult Australians from non-English speaking backgrounds have lower rates of risky alcohol use than English-speaking Australians (AIHW, 2014; Livingston, Laslett, & Dietze, 2008).

The variables used here describe these characteristics for the primary household. That is, while we include some analyses of drinking by parents living elsewhere, we have not analysed their or their households' characteristics in this chapter.

We also control for three risk factors that are proximal predictors of early drinking:

- birth order, as later-born children may be more likely to use alcohol (Argys, Rees, Averett, & Witoonchart, 2006);

- adolescents' pubertal status at age 12-13, as more advanced puberty, especially in girls, is associated with risky behaviour (Patton & Viner, 2007); and

- whether the adolescent has friends who drink alcohol. In longitudinal studies, affiliation with alcohol-using peers is usually the most robust predictor of an adolescent's own drinking (Leung, Toumbourou, & Hemphill, 2014).

We also test a simple mediation model examining whether mothers' short-term risky drinking is related to poorer parental monitoring, subsequently predicting a higher likelihood of adolescent drinking. Parental monitoring (reported by the study child's main carer, 95% of whom are the study child's mother) is considered at Wave 6, as this is most proximal to adolescents' reported alcohol use. The measure of parental supervision is calculated from the main carer's responses to six questions related to how well they know their child's close friends and their parents; how often they know where their child is and who they are with; and how strongly they agree with statements such as: "It is important that parents know where their child is and what they are doing all the time." The responses to these questions were combined to create a standardised measure of parental monitoring (with a mean of 0, variance of 1 and Cronbach's alpha 0.60). This scale was then divided into quartiles.

4.3 Levels of alcohol consumption among parents of young adolescents

In each wave of LSAC, parents of the study child are asked how often they have a drink containing alcohol. Table 4.2 provides a summary of the levels of alcohol consumption of mothers and fathers who provided information about how often they drank alcoholic drinks and how much alcohol they drank. Levels of alcohol consumption for mothers not living in the study child's primary household are not presented, as estimates are unreliable due to the small number of observations.

Notes: For each measure, column total plus the "Abstainer" percentage adds to 100.0. Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 5 and 6

When interpreting these figures, it is important to keep in mind that information about alcohol consumption was missing for 14% of fathers in the primary household, 48% of fathers living elsewhere and 42% of mothers living elsewhere (Table 4.1); and it is possible that the estimates of the level of alcohol consumption for these parents in Table 4.2 is not representative of the national population.

- Just over 20% of mothers in the primary household, and around 11% of fathers (in the primary household or living elsewhere) drank no alcohol at all.

- Only 23% of mothers in the primary household reported drinking more than two drinks per day on any occasion, compared to 44% of fathers in the primary household and 47% of fathers living elsewhere.

- The percentage of mothers who reported drinking more than five drinks on the same day at any time in the last year was 38%, compared to 65% of fathers in the primary household and 68% of fathers living elsewhere.

- However, only 11% of mothers and 30% of fathers in the primary household and 37% of fathers living elsewhere drank at this level (more than five drinks on one occasion) more than once a month.

- The majority of parents drank alcohol less often than four days a week. However, 4% of mothers living in the study child's primary household, 15% of fathers in the primary household and 16% of fathers living elsewhere) reported having at least three drinks per day at least 4 days a week.

4.4 Adolescent drinking at age 14-15

Adolescents at ages 12-13 (Wave 5) and 14-15 (Wave 6) were asked: "Have you ever had even part of an alcoholic drink?" Table 4.3 shows that while just over 40% of adolescents had had a few sips of an alcoholic drink by the age of 14-15, only 16% had drank at least one alcoholic drink; and there was no significant difference in the percentage of boys and girls who had ever had an alcoholic drink.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 5 and 6

Those who reported having had at least one alcoholic drink were asked how old they were when they had their first full serve (a glass) of alcohol. Table 4.4 shows that among the 16% of adolescents who had consumed at least one full serve of an alcoholic drink, it was more common for boys than for girls to have had a full serve of alcohol before the age of 13. Only 2.5% of all girls aged 14-15 had had an alcoholic drink before the age of 13, compared to 4.4% of boys. This difference is reflected in the average age at which boys and girls consumed their first full serve of alcohol. Although the difference between the average age of first alcoholic drink for boys and girls is only seven months, it is statistically significant.

Notes: Differences in average age are statistically significant at the 0.1% level. Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding. Sample excludes 12 study children who said they did not know how old they were when they had their first alcoholic drink or refused to answer this question.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 5 and 6

Of those who reported having at least one drink, the majority (93%) had consumed an alcoholic drink in the 12 months prior to their Wave 6 interview, but Table 4.5 shows that for most 14 and 15 year olds, drinking alcohol was not a regular practice, with only 7% of boys and 8% of girls saying they had had an alcoholic drink in the past four weeks. Differences by child gender were not statistically significant.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Wave 6

Furthermore, among those who reported having had an alcoholic drink in the past four weeks, more than half had not had a drink in the previous week (Table 4.6). Around one-third of boys and girls who reported having had an alcoholic drink in the past four weeks had had more than one drink in the last week, with boys having had an average of 3.9 and girls an average of 2.3 alcoholic drinks in the past week. Differences by child gender were not statistically significant, with the higher average for boys being a result of more of them being likely to say they had had a large number (20 or more) of alcoholic drinks in the last week.

Note: # Estimate not reliable (cell count less than 20). Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Wave 6

4.5 Characteristics associated with adolescents' drinking

In Table 4.7 and Table 4.8 we examine the association between adolescents' drinking and selected characteristics of the child and their family. The key outcome variable is whether the study child has had an alcoholic drink in the last 12 months. As we are interested in factors associated with adolescents' alcohol use that may have occurred up to 12 months prior to the Wave 6 interview, most of the characteristics analysed (including parents' alcohol use) are measured at Wave 5, when the study children were aged 12-13, rather than at Wave 6. One exception is the measure of whether the study child has friends who drink alcohol, which is measured at age 14-15 (Wave 6), as the likelihood of having friends who drink alcohol will change considerably between the ages of 12-13 and 14-15. Similarly, birth order is measured at age 14-15 to account for any siblings born within the last two years; and area of residence is measured at 14-15 to account for changes in residence since the Wave 5 interview.

As shown in Table 4.7, the following adolescent characteristics were significantly associated with adolescent drinking:

- Birth order: Almost 30% of girls and 19% of boys who were the only child reported having had an alcoholic drink in the past 12 months, compared to only 11% of adolescents who were the oldest child and 16% of those who were the youngest child in the family.

- Pubertal status: There were considerable differences in the percentage of adolescents who drank alcohol in the last 12 months depending on their pubertal status, with almost 20% of adolescents who were in the later stages of puberty reporting having at least one alcoholic drink, compared to 11% of those in the early stages of puberty.

- Friends' drinking: Adolescents with friends who drank alcohol were much more likely to drink. Almost half of the adolescents who said they had some friends who drank alcohol; and over 70% of adolescents who said most or all of their friends drank reported having had an alcoholic drink in the past year, compared to only 5% of those who said that none of their friends drank.

Notes: # Estimate not reliable, cell count less than 20. Number of observations ranges from 3,230 for pubertal status to 3,339 for Indigenous status. * Indicates that differences in the percentage of adolescents reporting having had an alcoholic drink in the past 12 months are statistically significant at the 5% level.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 5 and 6

As shown in Table 4.8, the following family characteristics were significantly associated with adolescent drinking.

- Family type and employment status:

- Compared to adolescents living with both their biological parents, the percentage of 14-15 year olds who drank alcohol in the past 12 months was almost double for those in single-mother households.

- Among adolescents living with two parents, the percentage of adolescents who drank alcohol was approximately 4 percentage points higher for those with two parents employed, compared to those whose father was in paid employment but their mother was not.

- Socio-economic position: Compared to adolescents living in households in the highest quartile of socio-economic position, the percentage of 14-15 year olds in households in the lowest quartile of socio-economic position who drank alcohol in the past 12 months was almost double.

Notes: # Estimate not reliable, cell count less than 20. Number of observations ranges from 2,984 for father's religion to 3,339 for remoteness. Family type, parents' employment status and socio-economic position are based on parents in the primary household only. * Indicates that differences in the percentage of adolescents' reporting having had an alcoholic drink in the past 12 months are statistically significant at the 5% level.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 5 and 6

- Parents' country of birth: Compared to adolescents whose mother was born in Australia, the percentage of adolescents who drank alcohol in the past 12 months was significantly lower among those whose mother was born in a mainly English speaking country other than Australia, and lower again among those whose mother was born in a non-English speaking country. For girls, but not for boys, differences according to their father's country of birth were also significant.

- Grandparents' problematic alcohol use: The percentage of adolescents who reported having an alcoholic drink in the last 12 months was approximately 5 percentage points higher for those who had at least one grandparent who had a problem with alcohol (reported by the parents of the study child).

4.6 The association between parents' drinking and their children's alcohol use

In this section, we describe the association between adolescents' alcohol consumption at age 14-15 and their parents' alcohol consumption two years before. This section concentrates on drinking by parents in the primary household (refer to section 4.7 for analysis of drinking by fathers living elsewhere) and presents bivariate analyses.9 Table 4.9 and Table 4.10 show the percentage of boys and girls who reported having at least one alcoholic drink by the time they were age 14-15, according to the level of alcohol consumption of their parents in their primary household.

Notes: Sample includes step, foster and adoptive mothers in the primary household, excludes mothers living elsewhere # Estimate not reliable, cell count less than 20. * Indicates that differences in the percentage of adolescents' reporting having had an alcoholic drink in the past 12 months are statistically significant at the 5% level.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 5 and 6

Compared to those whose mother did not drink alcohol at all, the percentage of adolescents who had an alcoholic drink in the last 12 months was 10 percentage points higher among those whose mother did drink alcohol (at any level and frequency). This difference was statistically significant (p < .05).

Among 14-15 year olds whose mother drank some alcohol:

- For girls, and overall, but not for boys, the percentage of adolescents who drank alcohol in the past 12 months was significantly higher among those whose mother drank at a long-term risky level (more than two drinks on any occasion in the last 12 months).

- For girls and boys, the percentage that drank at least one alcoholic drink in the last 12 months was significantly higher among those whose mother drank alcohol at the level considered to be risky in the short term (five or more drinks on any occasion).

- Comparisons for level of frequent drinking showed that the prevalence of drinking among adolescents whose mother frequently drank 1-2 drinks per day were not significantly higher than the prevalence of drinking among adolescents whose mother drank alcohol less often than four days per week. However, there was a significant difference between those whose mothers drank alcohol less frequently and those who had three or more drinks per day, at least four days a week (17% compared to 23%). This difference is significant overall but not for boys and girls separately, presumably due to the limited number of observations.

Notes: Sample includes step, foster and adoptive fathers in the primary household, excludes fathers living elsewhere. # Estimate not reliable, cell count less than 20. * Indicates that differences in the percentage of adolescents' reporting having had an alcoholic drink in the past 12 months are statistically significant at the 5% level.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 5 and 6. Sample restricted to adolescents with alcohol consumption data in Wave 6, whose primary carer was interviewed in Wave 5.

Turning now to the differences in the percentage of adolescents who reported drinking alcohol in the last 12 months, according to their father's levels of alcohol consumption, Table 4.10 shows that compared to those whose father did not drink alcohol at all, the percentage of adolescents who had an alcoholic drink in the last 12 months was 5 percentage points higher among those whose father did drink alcohol (at any level and frequency).10

Among adolescents whose father drank some alcohol:

- For girls and boys, the percentage of adolescents who drank alcohol in the past 12 months was significantly higher among those whose father drank at a long-term risky level (more than two drinks on any occasion in the last 12 months).

- Overall, and for girls (but not for boys when considered separately), the percentage who drank at least one alcoholic drink in the last 12 months was significantly higher among those whose father drank alcohol at the level considered to be risky in the short term (five or more drinks on any occasion).

- Compared to adolescents whose father drank alcohol less often than four days per week, the percentage who reported drinking alcohol in the last 12 months was significantly higher among those whose father reported having three or more alcoholic drinks per day, at least four days a week (19% compared to 12%).

In Table 4.11 the percentage of adolescents aged 14-15 who reported having at least one alcoholic drink in the last 12 months is compared according to whether they have one or two parents in their primary household and if either or both of their parents regularly drink at a level that is considered risky in the short term (i.e., five or more drinks on a single occasion, at least twice a month). For two-parent households, the sample is restricted to adolescents with information about the alcohol consumption of both parents. In single-parent households, the sample is restricted to adolescents with information available about that parent's level of alcohol consumption.

Notes: Risky drinking is defined as having five or more alcoholic drinks per day, at least twice per month. Sample is restricted to adolescents in two-parent households where information about both parents drinking is available and those in single-parent households (the majority in single-mother households) where the parent has provided information about their alcohol consumption. # Estimate not reliable, cell count less than 20. Significance (chi-square) tests indicate that for boys and girls, the proportions are different at the 5% significance level. * Indicates that differences in the percentage of adolescents' reporting having had an alcoholic drink in the past 12 months are statistically significant at the 5% level.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 5 and 6

The prevalence of having had a drink in the last 12 months was around 9% for adolescents in two-parent households where neither parent drank at a risky level. This increased to 16% for those whose father drank alcohol at the short-term risky level; and to 23% when both parents reported regularly drinking at the short-term risky level. Comparisons for adolescents whose mother (but not father) drank at a risky level were not possible due to small numbers of families where this was the case.

For adolescents in single-parent households (91% in single-mother households), the percentage that reported having an alcoholic drink in the last 12 months was 22% among those whose parent did not drink alcohol at a risky level. This percentage is almost as high as that of children living in a two-parent household in which both parents drank at risky levels. Further, among adolescents in single-parent households in which their parent reported drinking at a level that is considered risky in the short term, one-third reported having at least one alcoholic drink in the past 12 months.

The association between alcohol consumption of parents living elsewhere and their children's alcohol use

For adolescents with parents who do not live in their primary household, it is important to also consider the levels and frequency of alcohol consumption of the parent living elsewhere, if they have contact with the study child. The LSAC data are unique in having information about the alcohol consumption levels of parents who do not live in the primary household, allowing these associations to be tested for the first time. Table 4.12 shows that among adolescents with a father living elsewhere, the percentage that reported having at least one alcoholic drink (22%) in the past 12 months was considerably higher than the overall average of around 16% (see Table 4.3). Due to the small number of observations, we do not present a table of adolescent drinking according to the alcohol consumption of mothers who do not live in the primary household.

Note: # Estimate not reliable, cell count less than 20. ns Indicates that differences in the percentage of adolescents' reporting having had an alcoholic drink in the past 12 months are not statistically significant at the 5% level.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 5 and 6

While the percentage of adolescents who reported drinking alcohol in the past 12 months was higher among those with a father living elsewhere who drank alcohol, compared to those with a father living elsewhere who did not drink at all ("abstainer"), these differences were not statistically significant. This lack of statistical significance was influenced by the small number of observations for fathers living elsewhere who were abstainers. Similarly, among adolescents whose father living elsewhere did drink alcohol, differences in the percentage who reported having at least one alcoholic drink in the last 12 months were not statistically significant depending on whether their father drank at levels that were considered to be risky in either the short or the long term.

It is important to note that, in addition to the high level of non-response among parents living elsewhere and bias in this subsample, the influence of the alcohol consumption of a father who does not live in the primary household is likely to depend on the amount of contact the adolescent has with their father. However, due to the limited number of observations for non-resident fathers, this type of analysis is not possible.

4.7 Does parents' drinking predict the likelihood of adolescent drinking after controlling for socio-demographic risk factors?

In this section, we use a multivariate approach to examine the association between parents' alcohol consumption and adolescents' drinking. Our key variable of interest is whether adolescents have drunk alcohol in the last 12 months. To test for associations with parents' drinking our primary focus is on the measure of parents regularly drinking alcohol at a level that is considered risky in the short term - five or more drinks on any day, at least twice a month. This measure of parents' alcohol consumption was chosen as the descriptive evidence showed the largest differences in adolescents alcohol use.11

As there is a considerable amount of missing data about parents' alcohol consumption, particularly for fathers, the measures of parents' risky alcohol consumption are categorical variables, with four categories:

- parent does not drink at a risky level, including abstainers (reference category);

- parent drinks at a risky level;

- no information about parents' drinking; and

- no father/mother in the primary household.12

To estimate the association between parental drinking and adolescent drinking, we run five sets of logistic regressions, adding covariates in stages (Table 4.13).

- The baseline model (Model I) controls only for mother's risky alcohol consumption.

- In Model II, father's risky short-term drinking is added.

- In Model III, measures of the drinking levels of parents living elsewhere (mainly fathers) are added.

- In Model IV, characteristics of the child and their family are added to the model; and

- In Model V, an indicator of having at least one friend who drinks alcohol is added to the set of control variables. Friends' drinking is illustrated separately in Model V because of the magnitude of its relationship with adolescent drinking.

Regressions are run separately for boys and girls, as the descriptive evidence earlier in this chapter suggests that there are gender differences in the factors associated with adolescent drinking.13

Notes: *** p < .001, ** p < .01, and * p < .05. Covariates included in Models IV and V: birth order, quartile of socio-economic position, whether the study child speaks a language other than English, mother's country of birth, pubertal status category at age 12-13, Indigenous status, parental employment and an indicator of whether a grandparent had a problem with alcohol.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 5 and 6

Our estimates of the association between parents' and adolescents' drinking show that:

- Before controlling for any other factors, the baseline model (Model I) suggests that the odds of having had an alcoholic drink in the last 12 months for adolescents whose mother regularly drank at the short-term risky level was 2.2 times higher than that of those whose mothers did not drink at this level.

- When an indicator of father's risky drinking was included in the model (Model II), mother's alcohol consumption remained statistically significant for boys and girls. For girls, but not for boys, there was a significant additional effect of the father's alcohol consumption. That is, after controlling for the mother's risky drinking, the odds of having had an alcoholic drink in the last 12 months for girls whose father drank at a risky level were 2.5 times the odds for girls whose father did not drink at this level.

- Model III shows that the indicators of risky drinking of a parent living elsewhere were not statistically significant, and the results concerning the risky drinking of parents in the primary household were very similar to those for Model II. This does not necessarily mean that the alcohol consumption of parents living elsewhere has no significant influence on adolescents' alcohol use. It must be kept in mind that there was a considerable amount of missing data about the alcohol use of parents living elsewhere; and the results may be biased in the sense that parents living elsewhere who drink at risky levels may be less likely to have contact with their children (and therefore are less likely to complete the PLE questionnaire).

- After controlling for a range of covariates, including whether a grandparent had a problem with alcohol (Model IV), mother's risky drinking remained statistically significant for boys, and father's risky drinking remained significant for girls. For boys whose mother regularly drank at a risky level, the odds of having had an alcoholic drink were 2.6 times those of boys whose mother did not; and, for girls, the odds of having consumed an alcoholic drink were doubled if their father drank at a risky level. However, this does not necessarily mean that mother's alcohol consumption is not an important factor influencing adolescent girls' alcohol consumption; or that father's alcohol consumption is not an important factor in boy's alcohol use. This may reflect the combination of mother's and father's drinking where, for example, a significant coefficient for mother's drinking is an indicator of a household where both parents drink heavily. There may also be differences between the group of parents who provided information about their alcohol consumption and those who did not; and it is possible that the alcohol consumption of parents whose alcohol consumption data were missing consumed alcohol at higher levels than those who provided information about their alcohol consumption.14

- Having at least one friend who drank alcohol (Model V) was a very strong predictor of adolescents having had an alcoholic drink. When this indicator was included in the model, only mother's risky drinking remained significant for boys. This result suggests that there is some shared variance between parents' drinking and friends' drinking. That is, adolescents who had parents who drank at risky levels may be more likely to have friends who drank alcohol, and were also more likely to have tried alcohol themselves.

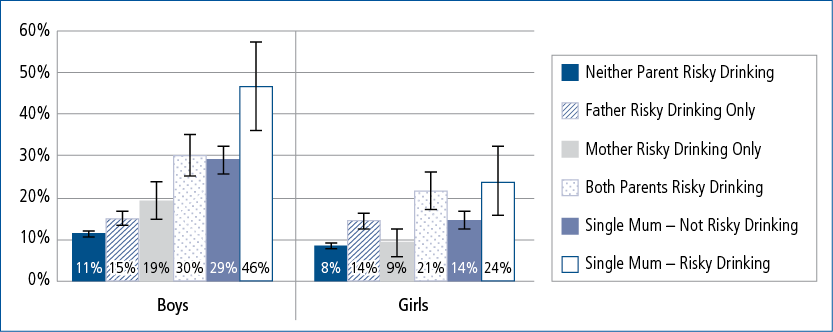

Figure 4.1 provides a summary of these results, showing predicted probabilities of having had an alcoholic drink, based on predicted probabilities calculated from Model V in Table 4.13.

Figure 4.1: Predicted probability of adolescents age 14-15 drinking (in the last 12 months), by levels of parents' risky drinking

Notes: Predicted probabilities derived from model IV for adolescents either in two parent households with information about both parents dinking, or single mother households with information about their mothers drinking. Predicted values are calculated at the sample average of all other variables included in the model. Sample size was too small to include predicted probabilities for single father households. The "I" bars represent 95% confidence intervals. "I" bars that do not overlap indicate there is a statistically significant difference between the groups.

- The predicted probabilities of 14-15 year olds having had an alcoholic drink in the last 12 months ranged from 8% for girls and 11.2% for boys in two-parent households in which neither parent drank at a risky level to 46.3% for boys in single-mother households in which the mother drank at a risky level.

- For boys and girls, the predicted probability of having had an alcoholic drink was highest among those in single-mother households in which the mother drank at a risky level.

- Among adolescents in two-parent households, the predicted probability of having had an alcoholic drink was significantly higher for those living in households where both parents drank at a risky level, compared to those in households where neither parent drank at a risky level.

- For boys, but not for girls, the predicted probability of having had an alcoholic drink was significantly higher for those in single-mother households where the mother drank at a risky level, compared to those in two-parent households where both parents drank at a risky level.15

4.8 Does poorer parental monitoring explain relationships between parent drinking and adolescent drinking?

This section addresses the final research question and examines whether the association between adolescents' drinking and parents' drinking is explained by poorer levels of parental monitoring among parents who consume alcohol at risky levels. There is some evidence that peer pressure to drink is more strongly related to adolescent alcohol use in the presence of poor parenting (Nash, McQueen & Bray, 2005). A large US study of young adolescents showed that effects of parental monitoring on adolescent drinking were mediated by peer effects and, taken together, parental monitoring and peer effects accounted for all variability in alcohol use by ethnicity and family structure (Wang, Simons-Morton, Farhart, & Luk, 2009). It is also possible that problem behaviour such as drinking and associating with deviant peers leads to decrements in parenting, as these children may be difficult to effectively monitor (Trucco, Colder, Wieczorek, Lengua, & Hawk, 2014).

Table 4.14 shows that the percentage of adolescents who reported having at least one alcoholic drink in the last 12 months was considerably higher among those receiving lower levels of parental monitoring, compared to those with high levels of parental monitoring. Almost one quarter of boys and 19% of girls who experienced low levels of parental monitoring reported having had an alcoholic drink, compared to 8% of boys and 11% of girls whose parents reported high levels of parental monitoring.

Notes: Significance (chi-square) tests indicate that the proportion who reported having had an alcoholic drink according to the main carers reports of parental monitoring are different: p < .05.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Wave 6

A structural equation model (mediation model) is used to examine whether the association between maternal alcohol consumption and adolescents' drinking is to some extent an indirect association, occurring via lower levels of parental monitoring among those parents who drink at risky levels.

As our measure of adolescent drinking is binary (0 if the adolescent has not had an alcoholic drink and 1 if they had), a generalised structural equation model is estimated and odds ratios are reported.

The sample is restricted to adolescents whose mother provided information about her alcohol consumption. This allows the "mother drinks at a risky level" variable to be measured as a binary variable. Similarly, the measure of "low parental monitoring" is set to 1 if the parental monitoring score is in the lowest quartile and zero otherwise. Measures of (resident and non-resident) father's risky drinking are included in the set of control variables, along with a set of socio-demographic characteristics including birth order, quartile of socio-economic position, whether the study child speaks a language other than English, mother's country of birth, pubertal status category at age 12-13 and an indicator of whether a grandparent had a problem with alcohol.

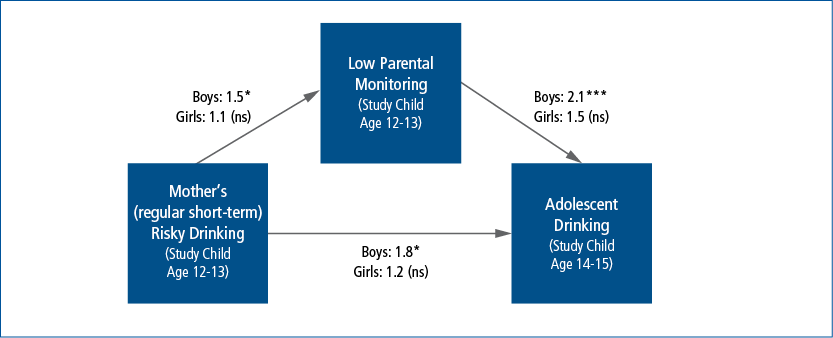

Estimates of the direct and indirect influence of mother's risky alcohol consumption on the odds of adolescent boys' and girls' drinking at age 14-15 are presented in Figure 4.2. Exponentiated coefficients are reported on the diagrams, so that a coefficient above 1 represents a positive influence (increasing the odds of having had an alcoholic drink) and a coefficient below 1 represents a negative influence.

Figure 4.2: The influence of mothers' risky alcohol consumption on the odds of adolescents' drinking at age 14-15

Note: *** p < .001, ** p < .01, and * p < .05. n.s. indicates a non-significant result. n = 1,309 for boys and 1,255 for girls. Controls include an indicator of risky drinking of a resident father and parent living elsewhere, birth order, quartile of socio-economic position, whether the study child speaks a language other than English, mother's country of birth, pubertal status category at age 12-13, Indigenous status, parental employment and an indicator of whether a grandparent had a problem with alcohol.

For example, for boys, the coefficient representing the association between mothers' risky drinking and low parental monitoring is 1.5. This means that for boys whose mother drank at a risky level, the odds of receiving low levels of parental monitoring are 1.5 times the odds of low levels of parental monitoring for boys whose mother did not drink at this level. Similarly, for boys who experienced low levels of parental monitoring, the odds of having had an alcoholic drink in the last 12 months were 2.1 times the odds of having had an alcoholic drink in the last 12 months for boys who experienced higher levels of parental monitoring. For boys, there is also a significant direct influence of having a mother who drank at a risky level, with the odds of having had an alcoholic drink being twice those for boys whose mother did not drink at this level. The significant direct and indirect influences of maternal risky drinking indicate that it is not only the influence of maternal drinking via a lack of parental monitoring that increase the likelihood of boys drinking if their mother drinks at this level.

For girls, there was no significant direct or indirect influence of maternal drinking on the odds of having had an alcoholic drink in the last 12 months. This is to be expected given the lack of significance of mother's risky drinking, once socio-demographic factors were controlled for in the logistic regression models presented in Table 4.13.

4.9 Summary and conclusion

This chapter documented the association between parental and adolescent drinking, exploring how this differed by gender of both parent and adolescent, and examined the role of parental monitoring in accounting for this association. Unlike many previous studies, we were able to describe levels of self-reported drinking in parents with reference to NHMRC guidelines in a large, nationally representative sample of 14-15 year old adolescents.

What are the levels of drinking among mothers and fathers of young adolescents?

- About 80% of mothers and almost 90% of fathers of adolescents had consumed some alcohol in the past 12 months. This is quite similar to population estimates from other survey data for males and females aged 35-64 (AIHW, 2014).

- Also consistent with national figures, the percentage of parents who drank at levels that exceeded guidelines for reducing both lifetime and single-occasion risk was high: about a quarter of resident mothers drank more than two drinks per occasion on average, and almost 40% had drunk more than four drinks on a single occasion at least once in the past 12 months.

- Although most parents did not drink daily, of those that did, more men exceeded guidelines for long-term risk (more than two drinks per day). Non-resident fathers drank at levels similar to resident fathers. Levels of risky drinking were substantially higher in non-resident mothers compared to resident mothers but because of the very small number, it was not possible to draw conclusions about this group of women.

- While many parents exceeded guidelines for minimising risk in the short and long term, a substantial minority drank at more risky levels. Around 11% of mothers and 30% of fathers reported drinking more than four standard drinks on a single occasion at least twice a month, and about 15% of fathers reported drinking more than two drinks per day on at least four days per week.

What are the levels of drinking among 14-15 year old adolescents; and what are the characteristics of those who drink alcohol?

- The percentage of 14-15 year olds who had had an alcoholic drink in the last 12 months was 14.8%, which is similar to the 15.2% of 12-15 year-olds in the 2013 National Drug Strategy Household Survey (AIHW, 2014).

- Adolescents who drank alcohol were likely to be more advanced in pubertal status at age 12-13, to be an only child or have older siblings, to have friends who drank alcohol at age 14-15, to have parents born in Australia or an English-speaking country, and to have a grandparent who had an alcohol problem. Several of these characteristics are risk factors for delinquent and problem behaviour more generally, highlighting the problematic nature of early-adolescent drinking.

- Being in the lowest quartile of socio-economic position also increased the likelihood of adolescent drinking. This result differs from the findings from contemporary UK research (Melotti et al., 2011), which found that drinking alcohol was more common among young people from higher-income households (but less common with higher levels of maternal education). However, this inconsistency may be due to differences in the age group being considered and the time frame when alcohol use was measured.16 It is also possible that differences in adolescents' alcohol use, by socio-economic position, are greater in Australia than in the UK. While there has been a considerable historical change toward Australian 13-14 year olds adopting NHMRC guidelines to not use alcohol, lower SES parents in Australia may have been slower to adopt these changes (Kelly, Goisis et al., 2016).

- The percentage of adolescents who had had a drink in the last 12 months was about double (25%) for those living in single-mother households compared to those living with both biological parents (12%).

How do different levels of mothers' and fathers' drinking relate to the probability of adolescent drinking, and does this vary by gender?

The following points summarise our descriptive analysis of the association between parents' drinking and the probability of adolescent drinking:

- Adolescents with parents who abstained from drinking were less likely to drink. Overall, the percentage of adolescents of abstaining parents who had had a drink in the last 12 months was less than half the percentage of adolescents of parents who had had a drink in the last 12 months. There may be many social, cultural and individual reasons why parents abstain from drinking, which are also correlated with less adolescent drinking. However, due to small numbers of abstainers, it was not feasible to explore abstention in multivariate models.

- For resident mothers and fathers who were current drinkers, drinking at a risky level was associated with increased rates of adolescent drinking. This was true for all drinking variables. For regular frequent drinking, rates of adolescent drinking were similar for those whose parents drank alcohol less than four days per week compared to those whose parents who drank alcohol four or more days per week within the guidelines for minimising long-term risk. However, rates of adolescent drinking were substantially higher if the regular drinking exceeded this long-term guideline. This top category of frequent drinkers overlapped substantially with those who regularly exceeded the short-term risk guidelines. This indicates that adults (and especially men) who have episodes of heavy drinking also tend to drink regularly. Thus, it is difficult to determine whether regular drinking (of any quantity) increases the risk for adolescent drinking, or whether this association occurs because regular drinking is likely to be accompanied by heavy drinking.

- In two-parent households, rates of adolescent drinking were highest when both parents were risky drinkers. It was unusual for a mother to exceed risk guidelines while the father did not. This applied to only 81 families (3.5% of two-parent households), making cross-tabulations with adolescent drinking unreliable.

- Rates of adolescent drinking were high in single-parent households, and higher still if the parent regularly exceeded the short-term guidelines. In single-parent households the rate of adolescent drinking when the parent did not drink at a risky level was as high as the rate for adolescents in two-parent households where both parents drank at a risky level. Single-parent households experience higher levels of social disadvantage. This may increase the likelihood of living in communities where rates of both adult and adolescent drinking are higher (Winstanley et al., 2008) and may also limit parental resources available to monitor adolescents and their friends (Chilcoat, Breslau, & Anthony, 1996). However, the relationships between family and community disadvantage, family structure and the onset of adolescent drinking remain unclear and should be the focus of further investigation with the LSAC data.

Does parents' drinking predict a higher likelihood of adolescent drinking after controlling for socio-demographic risk factors?

Multivariate modelling was used to examine whether the associations between parent drinking and adolescent drinking that were observed in simple cross-tabulations would persist after controlling for socio-demographic factors that are known to be risk factors for adolescent and/or parent alcohol use. For this analysis we focused on the regular short-term risk variable, which identified parents who drank more than four drinks on one occasion at least twice a month.

In general, results confirmed that parents' risky drinking did have unique associations with early adolescent drinking. However, the roles of mothers compared to fathers drinking and gender differences are still not clear. In models that controlled for all socio-demographic risk factors, except the adolescent's friends' drinking, results suggested that a mother's drinking was more strongly associated with drinking for boys, while a father's drinking was more strongly associated with drinking for girls.

The fact that fathers' drinking was not significant in the final model does not mean that fathers' drinking is not important. Indeed, this may reflect the combination of mothers' and fathers' drinking, where a significant coefficient for mothers' drinking is an indicator of a household where both parents drink heavily. Estimates of the predicted probability of adolescent drinking based on our multivariate models indicate that for adolescents in two-parent households, the predicted probability of having had an alcoholic drink was significantly higher if both parents drank at a risky level, compared to those in households where neither parent, or only one parent, drank at a risky level. Further, missing data on fathers' drinking was significantly associated with adolescent drinking in most models, suggesting that fathers who did not complete these items may have been heavier drinkers.

It was not surprising to see the coefficients for parents' drinking drop substantially after friends' drinking was included in the model (Leung et al., 2014; Scholte, Poelen, Willemsen, Boomsma, & Engels, 2008). This suggests that there is some shared variance between parents' drinking and friends' drinking: that adolescents who had parents who drank at risky levels at age 12-13 were more likely to have friends who drank alcohol at age 14-15, and were also more likely to have tried alcohol themselves. Parental monitoring is likely a key piece to this puzzle, as we discuss below.

Does poorer parental monitoring explain relationships between parental drinking and adolescent drinking?

The mediation model showed that risky maternal drinking when adolescents were aged 12-13 increased the odds of poorer monitoring of children's friends and activities two years later, which was subsequently associated with drinking for boys only. It is possible that parents who drink at risky levels have less organised rules around adolescent activities or other parenting difficulties (Dishion et al., 1999; King & Chassin, 2004). Findings like these suggest that reciprocal influences among parental drinking, parental monitoring, adolescents' behaviour and friends' behaviour need to be considered to understand the processes leading to early adolescent alcohol use.

Limitations

As mentioned, this study was limited by missing data for fathers' drinking. Future research with these data may benefit from exploiting the longitudinal information available in LSAC and using more complex missing-data techniques (e.g., multiple imputation) to account for this missing information. While dealing with this is challenging, the LSAC data represent a valuable opportunity to examine the usually neglected role of non-resident parents in adolescents' development.

Conclusions

The results showed that risky parental drinking increased the likelihood of adolescent drinking after controlling for a range of socio-demographic risk factors, including drinking among adolescents' friends. Moreover, poorer parental monitoring explained some of this association for boys. However, gender differences in the link between parent and adolescent drinking were not clear. Nor did the results confirm a "safe" level of parental drinking with regard to adolescent use.

Overall, the results suggested that parental drinking (especially if it is frequent and heavy) does increase the likelihood of early adolescent drinking but this association is probably only one part a complex developmental pathway involving parenting practices, family resources, community disadvantage, peer groups and alcohol availability.

4.10 References

Alati, R., Baker, P., Betts, K., Connor, J., Little, K., Sanson, A., & Olsson, C. (2014). The role of parental alcohol use, parental discipline and antisocial behaviour on adolescent drinking trajectories. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 134,178-184.

Argys, L., Rees, D., Averett, S., & Witoonchart, B. (2006). Birth order and risky adolescent behaviour. Economic Inquiry, 44(2), 215-233. doi:10.1093/ei/cbj011

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (ABS). (2015). National Health Survey: First Results, 2014-15. ABS Cat. No 4364.0.55.001. Canberra, ABS.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2014). National Drug Strategy Household Survey detailed report 2013 (Drug statistics series no. 28). Cat. no. PHE 183. Canberra: AIHW.

Baxter, J. A., Edwards, B., & Maguire, B. (2012). New father figures and fathers living elsewhere (FaHCSIA Occasional Paper No. 42). Canberra: FaHCSIA.

Bonomo, Y., Bowes, G., Coffey, C., Carlin, J., & Patton, G. (2004). Teenage drinking and the onset of alcohol dependence: A cohort study over seven years. Addiction, 99,1520-1528.

Chilcoat, H., Breslau, N., & Anthony, J. (1996). Potential barriers to parent monitoring: Social disadvantage, marital status, and maternal psychiatric disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 35, 1673-1682.

Coffelt, N., Forehand, R., Olson, A., Jones, D., Gaffney, C., & Zens, M. (2006). A longitudinal examination of the link between parent alcohol problems and youth drinking: The moderating roles of parent and child gender. Addictive Behaviors, 31,593-605.

Cortes, R., Fleming, C., Mason, W. A., & Catalano, R. (2009). Risk factors linking maternal depressed mood to growth in adolescent substance use. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 17(1),49-64. doi:10.1177/1063426608321690

Degenhardt, L., Stockings, E., Patton, G., Hall, W., & Lynskey, M. (2016). The increasing global health priority of substance use in young people. Lancet Psychiatry, published online 18 February. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00508-8

Dishion, T. J., Capaldi, D. M. & Yoerger, K. (1999). Middle childhood antecedents to progressions in male adolescent substance use: An ecological analysis of risk and protection. Journal of Adolescent Research, 14, 175-205.

Donovan, J., & Molina, B. (2011). Childhood risk factors for early-onset drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 72(5),741-751. doi:10.15288/jsad.2011.72.741

Duncan, S., Duncan, R., & Strycker, L. (2006). Alcohol use from ages 9-16: A cohort-sequential latent growth model. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 81(1), 71-81.

Duncan, S., Gau, J., Duncan, T., & Strycker, L. (2011). Development and correlates of alcohol use from ages 13-20. Journal of Drug Education, 41(3), 235-252.

Fergusson, D., Horwood, J., & Lynskey, M. (1995). The prevalence and risk factors associated with abusive or hazardous alcohol consumption in 16 year olds. Addiction, 90,935-946.

Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education. (2013). Annual alcohol poll: Attitudes and behaviours. Canberra: Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education.

Gilligan, C., & Kypri, K. (2012). Parent attitudes, family dynamics and adolescent drinking: Qualitative study of the Australian parenting guidelines for adolescent alcohol use. BMC Public Health, 12, 491.

Giskes, K., Turrell, G., Bentley, R., & Kavanagh, A. (2011). Individual and household-level socioeconomic position is associated with harmful alcohol consumption behaviours among adults. Aust NZ J Public Health, 270-277. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2011.00683.x

Hall, W., Patton, G., Stockings, E., Weier, M., Lynskey, M., Marley, K., & Degenhardt, L. (2016). Why young people's substance use matters for global health. Lancet Psychiatry, published online 18 February doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00013-4

Harrington-Cleveland, H., & Wiebe, R. (2003). The moderation of genetic and shared-environmental influences on adolescent drinking by levels of parent drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 64(2),182-194.

Hayes, L., Smart, D., Toumbourou, J., & Sanson, A. (2004). Parenting influences on adolescent alcohol use. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Hearst, M., Fulkerson, J., Malonado-Molina, M. Perry, C., & Komro, K. (2007). Who needs liquor stores when parents will do? The importance of social sources of alcohol among young urban teens. Preventive Medicine, 44(6), 471-476.

Hingson, R., & Zha, W. (2009). Age of drinking onset, alcohol use disorders, frequent heavy drinking, and unintentionally injuring oneself and others after drinking. Pediatrics, 123(6), 1477-1484. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-217

Hung, C., Chang, H., Luh, D., Wu, C., & Yen, L. (2015). Do parents play different roles in drinking behaviours of male and female adolescents? A longitudinal follow-up study. BMJ Open, 5. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007179

Jackson, K., Barnett, N., Colby, S., & Rogers, M. (2015). The prospective association between sipping alcohol by the sixth grade and later substance use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 76(2), 212-221.

Jacobus, J., & Tapert, S. (2013). Neurotoxic effects of alcohol in adolescence. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185610

Kelly, A., Toumbourou, J., O'Flaherty, M., Patton, G., Homel, R., Connor, J., & Williams, J. (2011). Family relationship quality and early alcohol use: Evidence for gender-specific risk processes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs,May,399-407.

Kelly, A. B., Chan, G. C., Weier, M., Quinn, C., Gullo, M. J., Connor, J. P., & Hall, W. D. (2016). Parental supply of alcohol to Australian minors: An analysis of six nationally representative surveys spanning 15 years. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 1.

Kelly, Y., Goisis, A., Sacker, A., Cable, N., Watt, R., & Britton, A. (2016). What influences 11 year olds to drink? Findings from the Millennium Cohort Study. BMC Public Health, 16, 169.

King, K., & Chassin, L. (2004). Mediating and moderating effects of adolescent behavioral undercontrol and parenting in the prediction of drug use disorders in emerging adulthood. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18,239-249.

Latendresse, S., Rose, R., Viken, R., Pulkkinen, L., Kaprio, J., & Dick, D. (2008). Parenting mechanisms in links between parents' and adolescents' alcohol use behaviors. Alcohol Clinical and Experimental Research, 32(2), 322-330.

Leung, R. Toumbourou, J., & Hemphill, S. (2014). The effect of peer influence and selection processes on adolescent alcohol use: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Health Psychology Review, 8(4), 426-457. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2011.587961

Livingston, M., Laslett, A., & Dietze, P. (2008). Individual and community correlates of young people's high-risk drinking in Victoria, Australia. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 98, 241-248.

Maloney, E., Hutchinson, D., Burns, L., & Mattick, R. (2010). Prevalence and patterns of problematic alcohol use among Australian parents. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 34(5), 495-501.

Mattick, R. P., Wadolowski M., Aiken A., Najman J.,Kypri, K., Slade, T. et al. (2015). Early parental supply of alcohol and alcohol consumption in mid-adolescence: A longitudinal study. in Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, p. 74a. Presented at the 38th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Research-Society-on-Alcoholism, San Antonio, TX, 20-24 June.

McGue, M., Malone, S., Keyes, M., & Iacono, W. (2014). Parent-offspring similarity for drinking: A longitudinal adoption study. Behavior Genetics, 44,620-628. doi:10.1007/s10519-014-9672-8

Melotti, R., Heron, J., Hickman, M., Macleod, J., Araya, R., & Lewis, G. (2011). Adolescent alcohol and tobacco use and early socioeconomic position: The ALSPAC birth cohort. Pediatrics, 127(4), e948-955. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3450

Mattick R. P., Wadolowski, M., Aiken, A., Najman, J., Kypri, K., Slade, T. et al. (2015). Early parental supply of alcohol and alcohol consumption in mid-adolescence: A longitudinal study. Presentation at the 38th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Research-Society-on-Alcoholism, San Antonio, TX, 20-24 June 2015.

Nash, S. G., McQueen, A., & Bray, J. H. (2005). Pathways to adolescent alcohol use: Family environment, peer influence, and parental expectations. Journal of Adolescent Health, 37(1), 19-28.

National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). (2009). Australian Guidelines to Reduce Health Risks from Drinking Alcohol. Canberra: NHMRC

Patton, G., & Viner, R. (2007). Pubertal transitions in health. Lancet, 369, 1130-1139. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60366-3

Peterson, P., Hawkins, D., Abbott, R., & Catalano, R. (1994). Disentangling the effects of parental drinking, family management, and parental alcohol norms on current drinking by black and white adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 4(2), 203-227.

Richmond-Rakerd, L.S., Slutske, W. S., Heath, A. C., Martin, N. G. (2014). Genetic and environmental influences on the ages of drinking and gambling initiation: Evidence for distinct etiologies and sex differences. Addiction, 109, 323-331.

Room, R., Ferris, J., Laslett, A.-M., Livingston, M., Mugavin, J., & Wilkinson, C. (2010). The drinker's effect on the social environment: A conceptual framework for studying alcohol's harm to others. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 7(4), 1855-1871.

Rossow, I., Keating, P., Felix, L., & McCambridge, J. (2016). Does parental drinking influence children's drinking? A systematic review of prospective cohort studies, Addiction, 11(2), 204-217.

Scholte, R. H., Poelen, E. A., Willemsen, G., Boomsma, D. I., & Engels, R. C. (2008). Relative risks of adolescent and young adult alcohol use: The role of drinking fathers, mothers, siblings, and friends. Addictive Behaviors, 33(1), 1-14.

Thompson, K., Roember, A. & Leadbeater, B. (2015). Impulsive personality, parental monitoring, and alcohol outcomes from adolescence through young adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57,320-326.

Tildesley, E., & Andrews, J. (2008). The development of children's intentions to use alcohol: Direct and indirect effects of parent alcohol use and parenting behaviors. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 22,326-339.

Trucco, E. M., Colder, C. R., Wieczorek, W. F., Lengua, L. J., & Hawk, L. W. (2014). Early adolescent alcohol use in context: How neighborhoods, parents, and peers impact youth. Development and Psychopathology, 26(2), 425-436.

Tyler, K., Stone, R., & Bersani, B. (2006). Examining the changing influence of predictors on adolescent alcohol misuse. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Use, 16(2),95-114. doi:10.1300/J029v16n02_05

van der Vorst, H., Engels, R. C., Meeus, W., Dekovic, M., & van Leeuwe, J. (2005). The role of alcohol-specific socialization in adolescents' drinking behaviour. Addiction, 100, 1464−1476. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01193.x

van der Zwaluw, C., Scholte, R., Vermulst, A., Buitelaar, J., Verkes, R., & Engels, R. (2008). Parental problem drinking, parenting, and adolescent alcohol use. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 31,189-200. doi:10.1007/s10865-007-9146-z

Vermeulen-Smit, E., Koning, I., Verdurmen, J., van der Vorst, H., Engels, R., & Vollebergh, W. (2012). The influence of paternal and maternal drinking patterns within two-partner families on the initiation and development of adolescent drinking. Addictive Behaviors, 37, 1248-1256.

Wang, J., Simons-Morton, B. G., Farhart, T., & Luk, J. W. (2009). Socio-demographic variability in adolescent substance use: mediation by parents and peers. Prevention Science, 10(4), 387-396.

Winstanley, E. L., Steinwachs, D. M., Ensminger, M. E., Latkin, C. A., Stitzer, M. L., & Olsen, Y. (2008). The association of self-reported neighborhood disorganization and social capital with adolescent alcohol and drug use, dependence, and access to treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 92(1), 173-182.

Young-Wolff, K., Enoch, M., & Prescott, C. (2011). The influence of gene-environment interactions on alcohol consumption and alcohol use disorders: A comprehensive review. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(5), 800-816. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.03.005

1 Alcohol causes the most health burden in eastern Europe, while the illicit drug burden is higher than that of alcohol in the USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and western Europe (Degenhardt et al., 2016).

2 For a review of the parent drinking-adolescent drinking literature refer to Rossow, Keating, Felix, and McCambridge (2016), for a more general review of parenting influences on adolescent drinking refer to Hayes, Smart, Toumbourou, and Sanson (2004), and for reviews of the behavioural genetic literature refer to Young-Wolff, Enoch, and Prescott (2011).

3 For the purposes of this analysis, the "primary household" is the household in which children are enumerated in the main LSAC interview. Many young people whose parents have separated or divorced will be living in shared care situations where the parent who does not live in the primary household provides a considerable amount of care for the child.

4 Parents who reported having had a drink containing alcohol (including those who had not had an alcoholic drink in the past year) were asked how many standard drinks they would have on a typical day when they were drinking; and how often they would have five or more standard drinks on one occasion. Because the outcome of interest is whether the study child had had an alcoholic drink in the past 12 months, our measures of risky alcohol consumption were constructed based on the information provided by parents in Wave 5, when the study child was aged 12-13. It should be noted that due to parental separation and other changes in household structure, some adolescents will not be living with the same mother/father in Wave 6 as they were in Wave 5.

5 In Waves 5 and 6 (ages 12-13 and 14-15), adolescents were asked "Have you ever had even part of an alcoholic drink?", and if so, at what age they had their first alcoholic drink. Wave 5 data was rolled forward for those who reported having had an alcoholic drink at age 12-13.

6 For the purposes of this analysis, "parents" include biological, step, foster and adoptive parents.

7 The NHMRC (2009) specifies four main guidelines. Guideline 1 relates to reducing the risk of alcohol-related harm over a lifetime: "For healthy men and women, drinking no more than two standard drinks on any day reduces the lifetime risk of harm from alcohol-related disease or injury." Guideline 2 relates to reducing the risk of injury on a single occasion of drinking: "For healthy men and women, drinking no more than four standard drinks on a single occasion reduces the risk of alcohol-related injury arising from that occasion." Guideline 3 relates to children and young people under 18 years of age: "For children and young people under 18 years of age, not drinking alcohol is the safest option." Guideline 4 relates to pregnancy and breastfeeding: "For women who are pregnant, planning a pregnancy or breastfeeding, not drinking is the safest option." Our measures of parental alcohol consumption are based on Guidelines 1 and 2.

8 Short-term risky drinking is quite common. For example, in the 2014-15 National Health Survey, 60-80% of 18-64 year old men who were current drinkers drank more than five drinks on a single occasion at least once in the past 12 months (Australian Bureau of Satistics [ABS], 2015). Presentations of some national surveys such as the National Drug Strategy Household Survey report short-term risky drinking as drinking five or more drinks at least once a month (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2014). The nearest approximation in the LSAC data is drinking five or more drinks on a single occasion at least twice a month.

9 Refer to section 4.8 for multivariate analyses that explores the associations between parents' drinking and adolescents' drinking.