3. Children’s housing experiences

3. Children’s housing experiences

For most Australians, whether owning or renting their home, the provision of housing for themselves and their families involves substantial expenditure throughout most of their lives. Housing costs are often the largest regular expense to be met from a household's current income (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2015). This chapter describes the types of housing that the LSAC study children live in, whether their parents own or rent, the condition of their homes and how often they relocate. The extent to which children experience (short-term or ongoing) housing stress and inadequate housing (e.g. overcrowding, housing in poor condition) is examined. Changes in the housing experiences of children who have moved house and the impact of family separation on housing experiences are also explored.

3.1 Types of housing

Data from the 2016 Census show that while separate houses still account for most homes in Australia (72%), there has been a large increase in other forms of dwelling. Higher density residential development, such as flats, apartments, semi-detached, row housing and town housing, now makes up 26% of all Australian housing (ABS, 2017).

The LSAC data show that most children live in a separate (detached) house. This is likely to be because of a preference among families for more living space, while single people and couples without children have a stronger preference for medium- and high-density housing. A 2011 study of housing preferences in Melbourne and Sydney showed that when making decisions about housing, the presence of children significantly altered households' priorities. The number of bedrooms was the most important consideration, followed by other dwelling features such as the number of living spaces and having a detached house (Weidmann & Kelly, 2011).

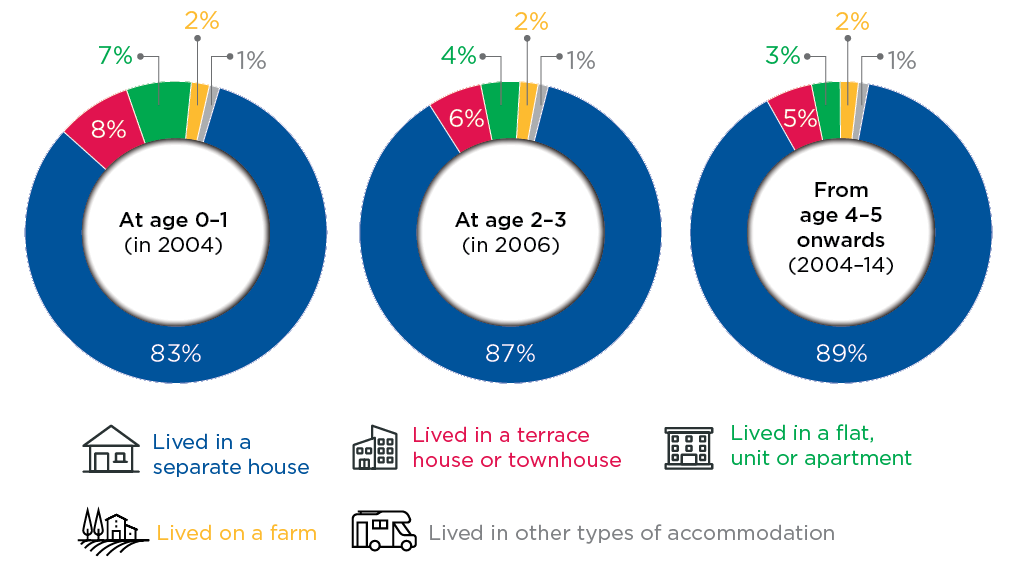

Among children in the LSAC B cohort, 83% lived in a detached house at age 0-1 (in 2004). By age 2-3, 87% were living in a detached house. From age 4-5 onwards, the overall percentage of LSAC study children living in each type of housing remained very stable, with almost 90% living in a separate house (Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1: Housing type, by age (2004-14)

Notes: n = 5,058 at age 0-1 (B cohort); 4,546 at age 2-3 (B cohort); 41,155 for ages 4-5 to 14-15 (B and K cohorts age 4-5 to 10-11 and K cohort age 12-13 and 14-15). Other accommodation includes caravan, cabin, house or flat attached to shop or office. Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Source: LSAC Waves 1-6, B and K cohorts, weighted

The type of housing that children live in varies depending on whether or not they live in a metropolitan area and, to a lesser extent, on household income. A higher percentage of children in low-income households live in higher density housing, compared to children in higher income households.

In metropolitan areas, for example, in 2014:

- Of 14-15 year olds in the lowest quartile of equivalised household income, 81% lived in a separate house, compared to 94% of those in households in the highest quartile of the equivalised income distribution.

- Among 14-15 year olds in the lowest quartile of household income:

- 11% lived in a terrace house or townhouse (compared to 3% of 14-15 year olds in households in the highest income quartile)

- 8% lived in a flat, unit or apartment (compared to only 2% of those in households in the highest income quartile).

In non-metropolitan areas, in 2014:

- Five per cent of 14-15 year olds were living on a farm, and there was no significant variation in this percentage according to household income.

- However, a higher percentage of 14-15 in households in the lowest quartile of income were living in medium-density housing, with 7% of those in households in the lowest quartile of equivalised household income living in semi-detached houses, terrace houses or townhouses, compared to only 1% of those in households in the highest quartile.

3.2 Housing tenure

Data from the ABS Survey of Income and Housing ([SIH], 2015) show:

- The proportion of Australian households that own their own home (with or without a mortgage) has declined from 71% in 1994-95 to 67% in 2013-14.

- The proportion of households that are renting from a private landlord has risen from 18% in 1994-95 to 26% in 2013-14.

The most recent census data confirm the shift towards renting, with 31% of Australian households now paying a landlord, up from 27% in 1991 (ABS, 2017).

The percentage of Australian households that own their home outright has also continued to decline, with 31% of households owning their home outright in 2016, compared to over 40% in 1991 (ABS, 2017).

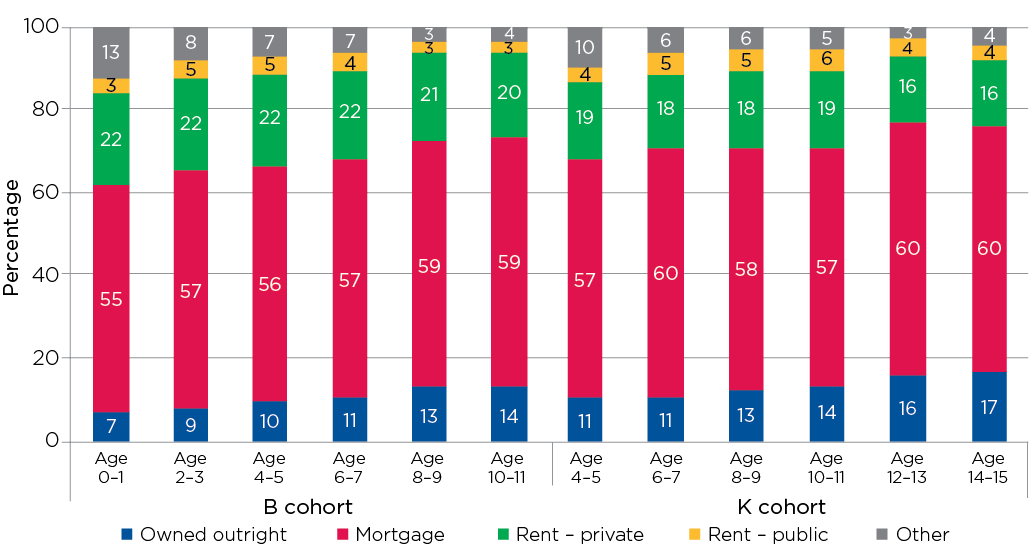

Across all waves of LSAC, the majority of study children (55-60%) lived in a household in which their parents were paying off a mortgage (Figure 3.2). The percentage of children living in a home that was owned outright increased with the age of the study child, with 7% of 0-1 year olds (in 2004) living in a home that was owned outright, compared to 17% of 14-15 year olds in 2014.

Box 3.1: Housing tenure

The classification of the housing tenure of the LSAC children's families is consistent with that used by the ABS (2015) in the SIH. Households where at least one parent owns the dwelling outright are defined as 'Owner without a mortgage'. If the study child's primary carer states that there is currently a mortgage or a secured loan against their dwelling, the household is classified as 'Owner with a mortgage'.

Renters are divided into two different types according to the type of landlord. Those who pay rent to a state or territory housing authority are classified as 'Renter - Public housing'. Those who pay rent to a private landlord who does not reside in the same household are classified as 'Renter - Private landlord'.

The category of 'Other housing' captures those who do not fit into the owner or renter categories, including those paying rent in caravan parks, those who rent from housing cooperatives or community organisations, those who occupy a dwelling rent free and those who occupy their dwelling as part of a life tenure, rent/buy or shared equity scheme.

Figure 3.2: Housing tenure, by cohort and age (2004-14)

Notes: n ranges from 5,100 (B cohort, age 0-1) to 3,451 (K cohort, age 14-15). 'Other' includes: those paying rent in caravan parks, those who rent from housing cooperatives or community organisations, those who occupy a dwelling rent free and those who occupy their dwellings as part of a life tenure, rent/buy or shared equity scheme. Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Source: LSAC Waves 1-6, B and K cohorts, weighted

The percentage of LSAC study children aged 10 or younger living in private rental accommodation remained quite stable, at around 20% across all waves (Figure 3.2). Among children aged 12-13 and 14-15 (in 2012 and 2014), the percentage in private rental accommodation decreased to 16%, as the percentage whose parents either owned their home outright or were paying off a mortgage increased. Living in other types of housing, such as a house or flat attached to a shop or office, or a caravan or cabin, became less common as children got older - from 13% of 0-1 year olds in 2004 to 4% of 10-11 year olds in the B cohort and 4% of 14-15 year olds in the K cohort in 2014.

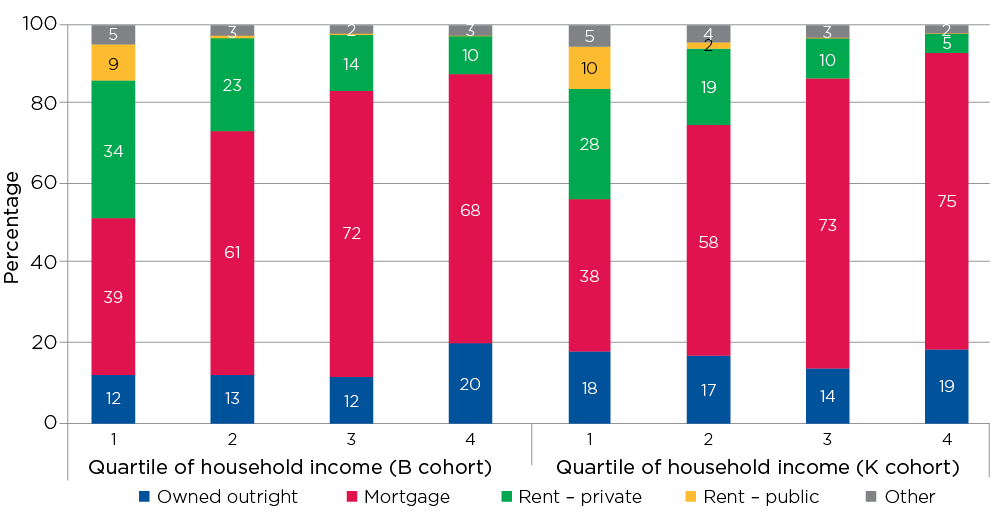

Housing tenure varies considerably depending on household income (Figure 3.3). In 2014, living in a privately rented home was much more common among children in households in the lowest quartile of household income. Among 10-11 year olds, for example, just over one-third of those in households in the lowest income quartile were living in a home that was privately rented, compared to 10% of those in the highest income quartile.

Children living in households at the higher end of the income distribution were more commonly living in homes that their parents were buying (with a mortgage) or owned outright. Almost 90% of 10-11 year olds and 94% of 14-15 year olds in households in the highest income quartile were in homes that their parents either owned or were buying, compared to less than 60% of children in households in the lowest quartile of household income.

Figure 3.3: Housing tenure, by quartile of equivalised household income, 2014

Notes: n = 3,915 for B cohort and 3,147 for K cohort. 'Other' includes: those paying rent in caravan parks, those who rent from housing cooperatives or community organisations, those who occupy a dwelling rent free and those who occupy their dwellings as part of a life tenure, rent/buy or shared equity scheme. Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Source: LSAC Wave 6, B and K cohorts, weighted

3.3 The cost of housing

Housing costs account for a significant part of household income. Across Australia, in 2014, owners with a mortgage paid an average of $453 per week, households renting from private landlords paid an average of $376 per week and households renting from state and territory housing authorities paid an average of $148 per week (ABS, 2015).

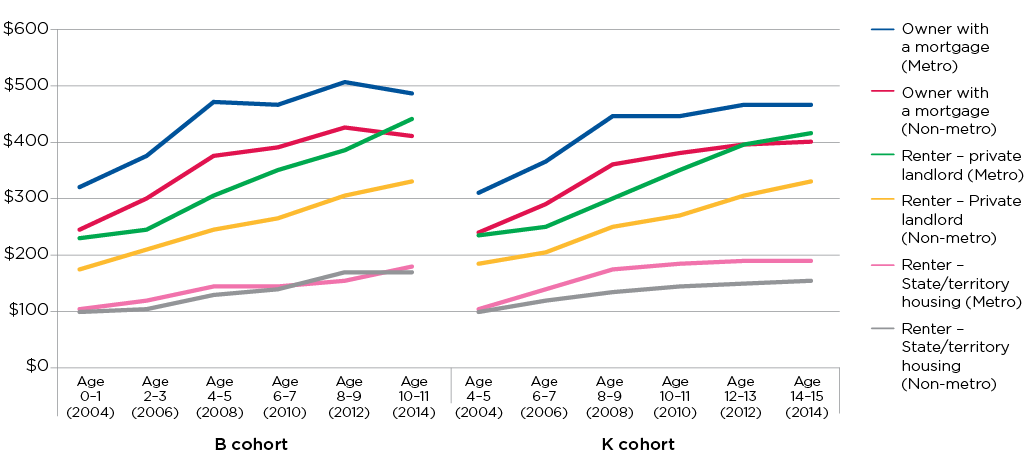

The LSAC data show that the average weekly cost of housing was highest for those families who were living in a metropolitan area and paying off a mortgage (Figure 3.4). The amount that families in metropolitan areas were paying for private rental accommodation increased considerably over the 10-year period between 2004 and 2014. While average rental payments in non-metropolitan areas were significantly lower than those in metropolitan areas, they also increased considerably over this period. However, the rate of increase was not as high as for those in metropolitan areas, particularly between 2008 and 2014.

By 2014, families in metropolitan areas paying rent to private landlords were paying more per week, on average, than those who were paying off a mortgage in a non-metropolitan area. This is consistent with ABS data for the Australian population, which show that for owners with a mortgage, the proportion of household income spent on mortgage costs fell from 18% in 2011-12 to 16% in 2013-14, as a result of an increase in mean gross household income and a period of low home-loan interest rates. However, private renters spent 20% of gross household income on housing costs in 2013-14, the same rate as 2011-12 (ABS, 2015).

Housing affordability stress is an important issue for the wider community, and especially for families. With the increasing cost of purchasing a home and a shift from mortgages to rental accommodation, many families are facing housing affordability stress, despite lower interest rates.

Figure 3.4: Average weekly cost of housing, by housing tenure and location, 2004-14

Notes: n ranges from 4,785 (B cohort, 2004) to 2,523 (K cohort, 2014). Values adjusted for inflation to 2014 dollars.

Source: LSAC Waves 1-6, B and K cohorts, weighted

Box 3.2: Housing affordability stress

The 30:40 indicator identifies households as being in housing affordability stress when the household has an income level in the bottom 40% of Australia's income distribution and is paying more than 30% of its income in housing costs.

The underlying assumption is that those on higher incomes who pay more than 30% of their income for housing do so as a choice and that such housing costs have little or no impact on the household's ability to buy life's necessities (Australian Household and Urban Research Institute [AHURI], 2016). The measure of housing stress in this chapter is based on gross rather than disposable household income.

Notes: n ranges from 5,100 (B cohort, 2006) to 3,027 (K cohort, 2014). Household income not available in Wave 1. Estimates of housing affordability stress for those in public rental and other accommodation not presented here due to the small number of observations.

Source: LSAC Waves 2-6, B and K cohorts, weighted

Overall, 10-14% of LSAC study children were living in a household experiencing housing stress in any particular wave. However, compared to children living in households where their parents were paying off a mortgage, where 7-9% were experiencing housing affordability stress, those living in rental accommodation were much more likely to be in households experiencing affordability stress. In 2014, around one-third of children in private rental accommodation were living in a household experiencing housing affordability stress (Table 3.1).

By definition, those experiencing housing affordability stress are in the lowest 40% of household incomes. Within this low-income group, it would be expected that households with incomes at the lower end of the income distribution would be more likely to experience financial stress and also housing affordability stress. Research using LSAC data has shown that, compared to children living with two parents, rates of poverty and financial disadvantage are considerably higher among children in single-parent households; and for the vast majority of children living in poverty, at least one parent had government payments as their main source of income (Warren, 2017).

Table 3.2 shows that among children in households with the lowest 40% of household incomes, the odds of living in a household experiencing housing affordability stress are:

- 1.5 times higher for those in private rental accommodation, compared to families paying a mortgage

- 1.6 times higher in metropolitan areas, compared to non-metropolitan areas

- almost 15 times higher in single-parent households, compared to couple households

- 4.3 times higher in households where at least one parent has government payments as their main source of income

- reduced by 50% if there are adults other than the study child's parents living in the household, compared to households with no other adults1

- around 1.5 times higher in all years after 2008, compared to 2006. This result suggests that, after considering factors such as housing tenure, household structure and location, housing affordability stress increased considerably around the time of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008 and, as of 2014, has not returned to pre-GFC levels.

Notes: Sample restricted to those in the lowest 40% of gross household income, n = 12,954. Random effects logistic regression * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

Source: LSAC Waves 2-6, B and K cohorts, unweighted

3.4 Housing quality

Many international studies have shown associations between housing circumstances and a range of child outcomes. Research has shown that there is a significant relationship between aspects of housing conditions and specific health outcomes; for example, cold, damp and mould were significantly associated with childhood asthma and respiratory conditions (Dockery et. al., 2010).

In Australia, housing conditions have been shown to be related to a variety of developmental outcomes, including physical health, socio-economic wellbeing and learning. A study of the association between housing conditions and children's developmental outcomes, using the LSAC data, found that while there was a statistically significant relationship between some housing-related factors and a child's physical health, socio-emotional wellbeing and learning outcomes, the role of housing in shaping children's wellbeing in Australia was quite modest overall (Dockery, Ong, Colquhoun, Li, & Kendall, 2013). While overcrowding had the largest negative impact for learning outcomes; frequent moves, renting rather than owning and being in financial stress were the aspects of housing that were shown to be negatively associated with children's social and emotional wellbeing.

In this section, the LSAC data are used to describe various aspects of housing quality, including overcrowding, neighbourhood liveability and interviewer-observed condition of the dwelling, and the factors associated with children's experiences of poor housing quality.

Overcrowding

In 2015-16, almost 4% of Australian households required at least one additional bedroom to meet the requirements of the household, while 78% of all households had one or more bedrooms more than the minimum number required, based on the Canadian National Occupancy Standard (CNOS) definition of overcrowding (ABS, 2017).& However, in households with dependent children, the percentage experiencing overcrowding was higher, with 6% of couple families with dependent children, 11% of single-parent households and 32% of multi-family households experiencing overcrowding in 2015-16 (ABS, 2017). Renters were less likely than home owners to occupy dwellings with more bedrooms than required, with around 60% of renters having surplus bedrooms, compared to 85% of home owners.

The LSAC data indicate that at age 2-3, 6% of children were living in overcrowded households (Table 3.3). By age 6-7, this percentage had increased to around 9% and, at age 14-15, 8% of study children were living in overcrowded housing.

Overcrowding was much more common among those in households in the lowest quartile of equivalised household income, where up to 20% of children were living in overcrowded conditions, compared to 2-3% of those in the highest quartile of equivalised household income.

Box 3.3: Overcrowding

A commonly used measure of crowding is the Canadian National Occupancy Standard (CNOS), which assesses the bedroom requirements of a household based on the following criteria:

- There should be no more than two persons per bedroom.

- Children less than five years of age of different sexes may reasonably share a bedroom.

- Children five years of age or older of opposite sex should have separate bedrooms.

- Children less than 18 years of age and of the same sex may reasonably share a bedroom.

- Single household members 18 years or older should have a separate bedroom, as should parents or couples.

Using this measure, households that require at least one additional bedroom are considered to experience some degree of overcrowding.

Note: #Estimate not reliable (cell count < 20).

Source: LSAC Waves 2-6, B and K cohorts, weighted

Table 3.4 shows that, after accounting for other factors, the odds of living in a household experiencing overcrowding are:

- 2.2 times higher in households in private rental accommodation and 3.8 times higher among those in public rental accommodation, compared to those living in homes owned outright

- 1.3 times higher in single-parent households, compared to couple households

- almost three times higher in households where at least one parent has government payments as their main source of income

- 1.5 times higher in households where no parent has a post-school qualification

- reduced by 27% for those in households in the highest quartile of equivalised household income, compared to households in the lowest quartile

- 14 times higher if there are adults other than the study child's parents living in the household, compared to households with no other adults

- higher in every interview year since 2008, compared to 2004.

Notes: n = 42,924. Random effects logistic regression * p< .05; ** p < .01; *** p< .001.

Source: LSAC Waves 1-6, B and K cohorts, unweighted

Neighbourhood liveability

Neighbourhood liveability is an important aspect of housing quality, as it is not just the house itself, but access to services and community spaces and also feeling safe in the area that you live in that has an influence on wellbeing.

The percentage of parents reporting low levels of neighbourhood liveability declined as children got older, with almost 7% of parents of 2-3 year olds in 2006 reporting low levels of neighbourhood liveability, compared to 3% of parents of 10-11 year olds and 4% of parents of 14-15 year olds in 2014 (Table 3.5).

Across all waves of LSAC, children in lower income households were more likely to live in 'less liveable' neighbourhoods. For example, among children aged 2-3 in 2006, 11% of those in the lowest quartile of equivalised income were living in a neighbourhood that their parents rated low on the liveability scale, compared to 4% of children in households in the highest quartile of equivalised household income.

Box 3.4: Neighbourhood liveability

The LSAC data included a series of questions relating to the liveability of the neighbourhood and available neighbourhood facilities. The responding parent was asked their agreement on a four-point scale with the statements:

- This is a safe neighbourhood.

- There are good parks, playgrounds and play spaces in this neighbourhood.

Responses to these questions were averaged to create the neighbourhood liveability scale. In most waves of LSAC, the scale had a range of 1-4, where 1 means 'strongly agree' and 4 means 'strongly disagree'. Those with a score of 3 or higher were considered to be living in a neighbourhood with poor liveability. However, in Wave 5, the neighbourhood liveability questions were asked on a scale of 1-5 and those with scores of 3.5 or higher were considered to be living in a neighbourhood with poor liveability.

Although additional questions relating to access to public transport and facilities such as shops, banks and medical services were asked in some waves, only the two questions above were asked in all waves. Therefore, the liveability scale used in this analysis is based on these two items.

Note: #Estimate not reliable (cell count < 20).

Source: LSAC Waves 2-6, B and K cohorts, weighted

Interviewer observations of housing conditions

Interviewer observations were used to assess characteristics of the home environment including clutter, noise and the condition of the exterior of the home. Around 5% of children were living in households that were described by their interviewer as being in poor or badly deteriorated conditions, with poor external conditions more common for those in lower income households (Table 3.6). While the percentage of children living in homes in poor external condition ranged from 9-13% among those in households with equivalised household income in the lowest quartile, very few children in households in the top half of the equivalised income distribution (up to 3% in the third quartile and less than 2% in the highest quartile) were living in homes that the LSAC interviewers described as being in poor external condition.

Box 3.5: External condition of the dwelling

Interviewers were asked to record observations about the study child's home, including the external condition of the dwelling. The external condition was rated on a scale of 1-4, with 1 meaning 'badly deteriorated', 2 'poor condition with paint peeling and in need of repair', 3 'fair condition' and 4 'well-kept with good repair and exterior surface'.

Note: #Estimate not reliable (cell count < 20).

Source: LSAC Waves 2-6, B and K cohorts, weighted

3.5 Moving house and changes in housing quality

Australian families move house quite often. In 2013-14, 1.26 million households (14% of all households) moved house at least once in the previous 12 months (ABS, 2015). While the percentage of couple families with dependent children that had moved at least once in the last 12 months was 14%, similar to that for all households, 21% of single parents with dependent children had moved at least once in the previous 12 months.

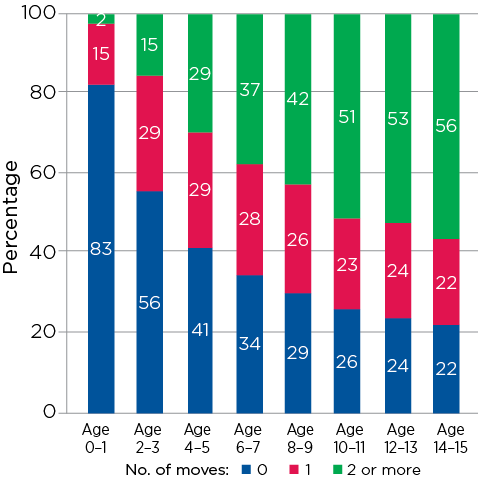

At age 0-1, 17% of children had moved at least once. By age 14-15, only 22% had remained in the same home for their entire life - 22% had moved once and 56% had moved house at least twice since birth (Figure 3.5).

Several large-scale studies from the United States have shown that higher levels of residential mobility have a negative influence on children's wellbeing. This is mainly due to disruptions to social connections within neighbourhoods, particularly if children have to move schools and make new friends (Boyle, 2002; Dockery et al., 2010; Harkness & Newman, 2005; Jelleyman & Spencer, 2008). Using LSAC, Taylor and Edwards (2012) found that the developmental outcomes of children may be more sensitive to residential mobility between the ages of four and five years than at older ages. However, it may be the change in family circumstances around the time of the move, such as parental separation, or changes in parents' work arrangements, resulting in a reduction in household income, rather than the move itself, that contributes to these poorer outcomes.

Figure 3.5: Number of house moves since birth

Notes: Cohorts are combined for ages 4-5 to 10-11. No significant difference in number of homes, by age of study child, between cohorts. Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Source: LSAC Waves 1-6, B and K cohorts, weighted

For many children, moving house is likely to be a positive experience, particularly if it involves an improvement in housing quality or moving to a better neighbourhood.

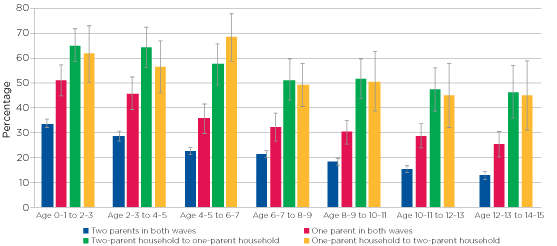

The LSAC data show that changes in household structure are often associated with a residential move.2 The percentage of children who had moved house at least once since the previous wave of LSAC was considerably higher among those whose primary carer had either separated or re-partnered during that time (Figure 3.6). For example, among children whose parents had separated between the time that they were aged 4-5 and 6-7, more than half had moved house, compared to 35% of those who were living with only one parent at both ages, and just over 20% of those who had remailed in a two parent household.

Moving house became less common as children got older, but even at age 14-15, over 40% of those who had experienced a change in household structure had moved house in the previous two years, compared to a quarter of teens who had remained in a single-parent household, and only 13% of those who had remained in a two-parent household.

When families move house, most do not move very far. For at least 40% of children, their family's most recent move was within the same town or suburb, and a further 35-40% had moved within the same area or region. To some extent, the distance that families move depends on the reason for the move. Among children whose families moved house when they were between the ages of 0-1 and 2-3, for example, 57% of those whose parents had separated moved somewhere within the same town or suburb, compared to 44% of those whose parents did not separate around the time of moving house.

Changes in housing conditions

For most children who had lived in a household experiencing housing affordability stress, this was a temporary situation, with 14% of children in the B cohort and 13% of children in the K cohort experiencing housing stress in two or more waves (Table 3.7). In terms of overcrowding, almost one in five children had lived in overcrowded conditions in at least one wave, while 11-12% had lived in overcrowded conditions in two or more waves. Similarly, around 15% of children had lived in a home that the interviewer considered to be in poor external condition in at least one wave but only around 6% lived in a home in poor external condition in two or more waves.

Figure 3.6: Housing mobility (percentage who moved since the previous wave), by change in parents' relationship status

Notes: Cohorts are combined for ages 4-5 to 10-11. n ranges from 4,606 between age 0-1 and 2-3 to 3,266 between age 12-13 and 14-15.

Source: LSAC Waves 1-6, B and K cohorts, weighted

Notes: Balanced panel. Housing affordability based on Waves 2-6. Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Source: LSAC Waves 1-6, B and K cohorts, weighted

To a large extent, neighbourhood liveability is beyond the control of individuals, and improvements in neighbourhood liveability are generally achieved only by moving to a different neighbourhood. Almost 20% of children experienced poor neighbourhood liveability in at least one wave, but only 2-3% were living in neighbourhoods with poor liveability for three or more waves. However, it is possible that the persistence of housing difficulties is underestimated somewhat, as those in households who were experiencing housing difficulties had significantly lower response rates in the subsequent wave of LSAC.3

Looking at changes in housing conditions from one wave of LSAC to the next, study children who remained in two-parent households were the least likely to experience housing affordability stress, with 86% who had moved house and 90% who had not moved since the previous wave experiencing no housing affordability stress (Table 3.8). On the other hand, at least one in four children who had remained in a single-parent household for two consecutive waves had remained in a situation of housing affordability stress.

Among children whose parents had separated since the previous wave, 41% of those who had moved house and 30% of those who had remained in the same home had moved into a situation of housing affordability stress. On the other hand, those whose primary carer had re-partnered since the previous wave were most likely to have moved out of housing stress, with 39% of those who had moved and 26% of those who had stayed in the same home no longer living in a household experiencing housing affordability stress.

Notes: Pooled data (n = 24,224). #Estimate not reliable (cell count < 20). Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Source: LSAC Waves 2-6, B and K cohorts, weighted

While a high percentage of children with parents who had recently separated were living in households experiencing housing affordability stress, only 10% of children who had moved house around the time their parents separated had moved into overcrowded conditions (Table 3.9). Around 12% of children whose primary carer had re-partnered since the previous wave had moved into overcrowded conditions, regardless of whether or not they had moved house. As a change from a single-parent to a two-parent household makes no difference to the overcrowding measure, this change is presumably because of new (step- or half-) siblings in the household.

Notes: Pooled data (n = 27,339). #Estimate not reliable (cell count < 20). Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Source: LSAC Waves 1-6, B and K cohorts, weighted

Among those who had moved house since their last interview, only 4% had moved into a neighbourhood that their parents rated 'poor' in terms of liveability, while 6% moved into a better (more liveable) neighbourhood (Table 3.10).

Most children who had moved house around at the time their parents separated had not moved into a worse neighbourhood in terms of liveability - only 3% had moved into neighbourhoods that their parents rated poor on the neighbourhood liveability scale, while 6% had moved to a more liveable neighbourhood. Among those who changed from a single-parent to a two-parent household around the time of their move, 8% had moved from a 'poor liveability' neighbourhood to a more liveable neighbourhood.

Notes: Pooled data (n = 8,252). Sample restricted to those who moved house since the previous wave. #Estimate not reliable (cell count < 20). Percentages may not total exactly 100.0% due to rounding.

Source: LSAC Waves 1-6, B and K cohort, weighted

Among children who had moved house since the previous wave, only 3% had moved from a house in good external condition to a house that was in poor condition (Table 3.11). For most children, living in a dwelling considered to be in poor condition was not an ongoing issue, with 9% of children in single-parent households and 7% of children whose parent had re-partnered moving from a home in poor or badly deteriorated condition to a home in good external condition.

Notes: Pooled data (n = 9,291). Sample restricted to those who moved house since the previous wave. #Estimate not reliable (cell count < 20).

Source: LSAC Waves 1-6, B and K cohort, weighted

Summary

This chapter has provided a picture of the housing experience of Australian children between 2004 and 2014. The LSAC data show that while most children do not live in households experiencing issues such as housing affordability stress, overcrowding or poor neighbourhood liveability, there are some whose families do face these issues. For most families who experience difficulties with housing, these are not ongoing issues.

Around 6% of study children were living in a home that was considered to be in poor external condition in two or more waves of LSAC; and a similar percentage had experienced two or more waves of poor neighbourhood liveability. One in 10 children experienced housing affordability stress or overcrowding in at least two waves of LSAC.

For some children, changes in housing are a result of parental separation and, in these cases, housing affordability is more likely to be an issue. Of children who moved house around the time of their parents' separation, 41% moved into a situation of housing affordability stress.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2015). Housing occupancy and costs, 2013-14, ABS Cat. No. 4130.0. Canberra: ABS. Retrieved from www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/4130.0~2013-14~Main%20Features~Key%20Findings~1

ABS. (2017). Housing occupancy and costs, Australia, 2015-16, ABS Cat. No. 4130.0. Canberra: ABS. Retrieved from www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/4130.0~2013-14~Main%20Features~Key%20Findings~1

Australian Household and Urban Research Institute (AHURI). (2016). Understanding the 30:40 indicator of housing affordability stress (AHURI Research Brief). Melbourne: AHURI. Retrieved from www.ahuri.edu.au/policy/ahuri-briefs/2016/3040-indicator

Baxter, J. (2016). The Modern Australian Family (AIFS Facts Sheet). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from aifs.gov.au/sites/default/files/families-week2016-final-20160517.pdf

Bleby, M. (2017, 27 June) Census 2016: Six-person households surge 21%, rental stress rises. Australian Financial Review. Retrieved from www.afr.com/real-estate/census-2016-sixperson-households-surge-21pc-rent...

Boyle, M. H. (2002). Home ownership and the emotional and behavioural problems of children and youth. Child Development, 73(3), 883-892.

Dockery, A. M., Kendall, G., Li, J. H., Mahendran, A., Ong, R., & Strazdins, L. (2010). Housing and children's development and wellbeing: A scoping study (AHURI Final Report No. 149). Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.

Dockery, A. M., Ong, R., Colquhoun, S., Li J. H., & Kendall, G. (2013). Housing and children's development and wellbeing: evidence from Australian data (AHURI Final Report No. 201). Melbourne: AHURI. Retrieved from www.ahuri.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0015/2067/AHURI_Final_Report_No2...

Harkness, J., & Newman, S. J. (2005). Housing affordability and children's wellbeing: Evidence from the National Survey of America's Families. Housing Policy Debate, 16(2), 635-666.

Jelleyman, T., & Spencer, N. (2008). Residential mobility in childhood and health outcomes: A systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 62, 584-592.

Taylor, M., & Edwards, B. (2012). Housing and children's wellbeing and development: Evidence from a national longitudinal study. Family Matters, 91, 47-61.

Warren, D. (2017) Low income and poverty dynamics: Implications for child outcomes (Social Policy Research Paper Number 47). Canberra: Department of Social Services.

Weidmann, B., & Kelly, J-F. (2011). What matters most? Housing preferences across the population. Melbourne: Grattan Institute. Retrieved from grattan.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/109_what_matters_most.pdf

1 Data from the 2016 Census show that there has been a growth in larger households, as rented dwellings account for a larger share of Australia's housing stock; and rental stress is prompting a greater proportion of adult children to stay or move back home (Bleby, 2017). Presumably, housing stress will be reduced by having other adults in the household who are able to contribute to housing expenses (and total household income).

2 Between each wave of LSAC 4-5% of study children went from being in a two-parent household to a one-parent household and 2-3% went from being in a one-parent household to a two-parent household. The percentage of study children who remained in a two-parent household between waves ranged from 85% between ages 0-1 and 2-3 to 78% between ages 12-13 and 14-15; while the percentage who remained in a single-parent household between waves increased from 8% between ages 0-1 and 2-3 to 16% between ages 12-13 and 14-15. See Baxter (2016) for more detailed analysis of changes in family structure in LSAC.

3 For example, among 12-13 year olds who were living in a household experiencing housing affordability stress in 2012, the response rate in 2014 was 79%, compared to 88% for those who were not in households experiencing housing affordability stress in 2012. Similarly, among 12-13 year olds who were living in overcrowded conditions in 2012, the response rate in 2014 was 77%, compared to 87% for those who were not living in overcrowded conditions in 2012.

Acknowledgements

Featured image: © GettyImages/JulieanneBirch