5. Relationships between parents and young teens

5. Relationships between parents and young teens

Parent-child relationships evolve as children grow. This is particularly the case as children enter adolescence and their independence and relationships with peers become more central to their lives (Hill, Bromell, Tyson, & Flint, 2007; Steinberg & Silk, 2002). Despite this increased focus on peers, family relationships remain central to children's lives during the early adolescent years and remain positive for many adolescents (Smart, Sanson, & Toumbourou, 2008). Research has shown that a positive parent-child relationship is predictive of better outcomes for adolescents (Fosco, Stormshak, Dishion, & Winter, 2012; Hoeve et al., 2009; Steinberg & Silk, 2002). Understanding how parent-child relationships develop as children move into adolescence can provide insights that may help families, teachers and service providers best support these relationships in this important period of life.

This chapter describes parent-child relationships at ages 10–11, 12–13 and 14–15 years. The quality of adolescents' relationships with parents is explored using a number of measures that provide different views on this relationship. These measures include children's reports of enjoyment in spending time with their parents; their closeness to their mother and father; who they talk to when they have a problem; and parents' reports of conflict with their children. In this chapter, we focus on relationships with parents who are living in the study child's main household.1

5.1 Enjoying time spent with parents

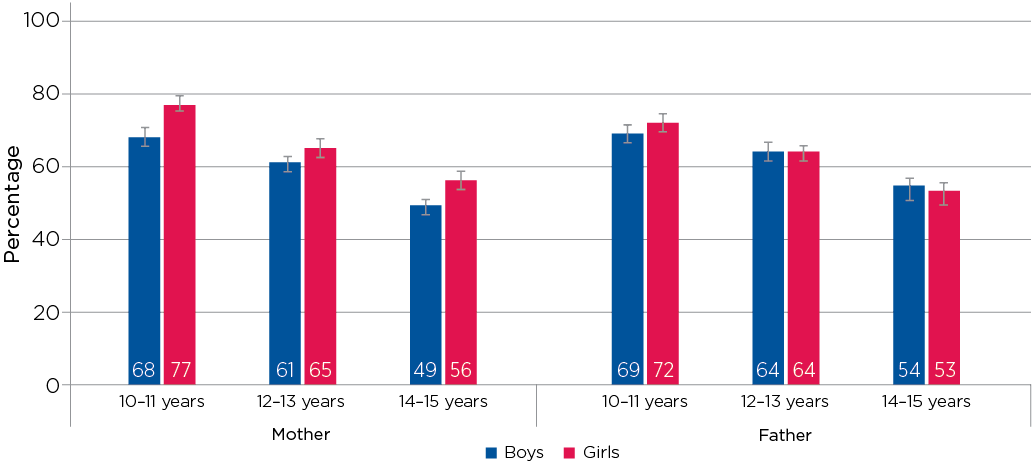

The majority of young people aged 10–11, 12–13 and 14–15 years said that they enjoyed spending time with their parents, with a substantial proportion saying it was 'definitely true' (Figure 5.1). However, the percentage of boys and girls who said they enjoyed spending time with their mothers and fathers ('definitely true') decreased as study children got older - from around 70% at age 10–11 to just over 50% at age 14–15.

Across all age groups, a higher percentage of girls than boys reported that they definitely enjoyed spending time with their mother, but similar percentages of boys and girls said that they definitely enjoyed spending time with their father.

Box 5.1: Enjoying time spent with parents

At ages 10–11, 12–13 and 14–15 years, LSAC study children were asked whether it was 'definitely true', 'mostly true', 'mostly not true' or 'definitely not true' that they enjoyed spending time with their mother and with their father.

Figure 5.1: Enjoyment of time spent with parents, by age and gender of study child

Notes: The percentages refer to study children's reports that it was 'definitely true' that they enjoy time spent with their father and their mother. For reports about mothers, n = 3,986 at 10–11 years, 3,726 at 12–13 years and 3,240 at 14–15 years. For reports about fathers, n = 3,346 at 10–11 years, 3,161 at 12–13 years and 2,734 at 14–15 years.

Source: LSAC Waves 4, 5 and 6, K cohort, weighted

5.2 Closeness with parents

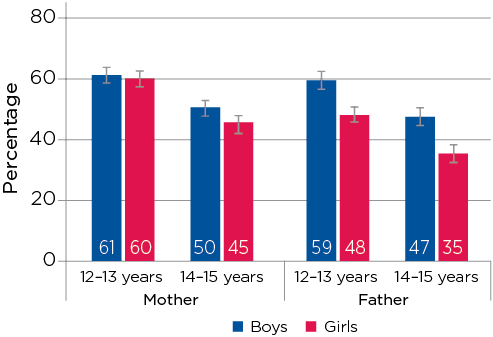

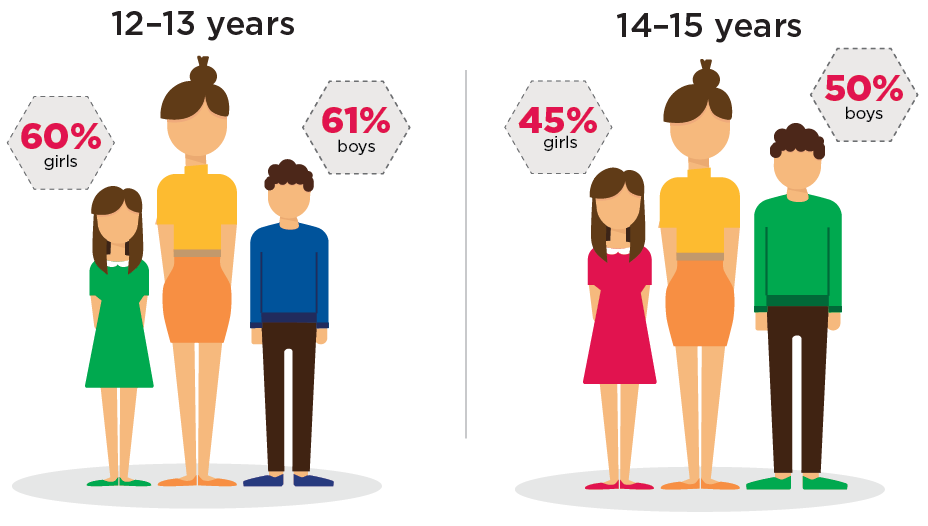

Most adolescents said that they felt either 'very close' or 'quite close' to their mother and father. However, the proportion of adolescents reporting feeling 'very close' to their mothers and their fathers decreased between 12–13 and 14–15 years (Figure 5.2 and Figure 5.3).

Box 5.2: Closeness with parents

At ages 12–13 and 14–15 years, LSAC study children were asked to choose from 'very close', 'quite close', 'not very close' and 'not close at all' in responding to the question, 'How close do you feel to your mum/dad?'.

At age 12–13, around 60% of boys and girls said that they were very close to their mother. By age 14–15, 50% of boys and only 45% of girls said they were very close to their mother.

For boys, the percentage reporting being very close to their father was similar to that for their mother. However, fewer girls reported being very close to their fathers than to their mothers - at age 14–15, 47% of boys, but only 35% of girls, said that they were very close to their father.

The percentage who said that they enjoyed spending time with their mother and father was higher than the percentage who said they were very close with each parent, particularly for girls. For example, while 53% of girls at 14–15 years old said they enjoy spending time with their father, only 35% said they felt very close. This suggests that for some adolescents, especially girls, time spent with their parents is enjoyable, even though they don't consider their relationship to be a very close one.

Figure 5.2: Adolescents' reports of feeling very close to their parents at 12–13 and 14–15 years

Notes: For reports about mothers, n = 3,691 at 12–13 years and 3,199 at 14–15 years. For reports about fathers, n = 3,007 at 12–13 years and 2,591 at 14–15 years.

Source: LSAC Waves 5 and 6, K cohort, weighted

Figure 5.3: Boys and girls who reported they were very close to their mother

5.3 Going to parents with problems

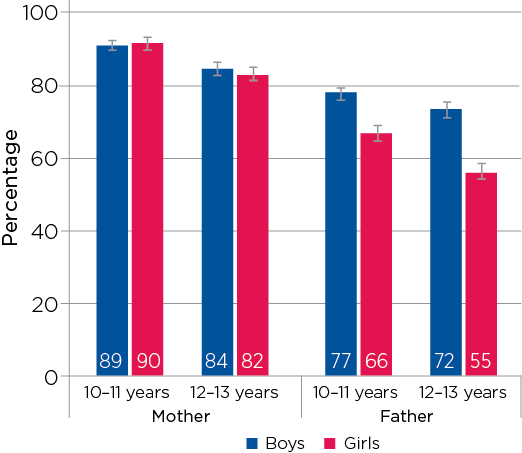

Young people's ability and willingness to talk to their parents about problems is an important indicator of a healthy parent-child relationship. The LSAC data show that most 10–11 and 12–13 year olds felt comfortable talking to either of their parents if they had a problem.

Box 5.3: Who would you go to if you had a problem?

At ages 10–11 and 12–13 years, LSAC study children were asked who they would go to if they had a problem. They were given a list of possible people including their mother, their father, other relatives, friends and teachers.

They could choose as many people as they liked from the list.

Overall, adolescents were more likely to say that they would go to their mother if they had a problem, rather than their father. It was less common for children to say they would go to a parent about a problem at age 12–13 than it was at age 10–11 (Figure 5.4).

- At age 10–11, around 90% of boys and girls said they would go to their mother if they had a problem. Only 77% of boys and 66% of girls said they would go to their father.

- At age 12–13, over 80% of boys and girls said they would go to their mother with a problem. Only 72% of boys and 55% of girls said they would go to their father.

Figure 5.4: Children's reports of who they would go to with problems, at 10–11 and 12–13 years

Notes: For reports about mothers, n = 4,066 at 10–11 years and 3,846 at 12–13 years. For reports about fathers, n = 3,429 at 10–11 years and 3,250 at 12–13 years.

Source: LSAC Waves 4 and 5, K cohort, weighted

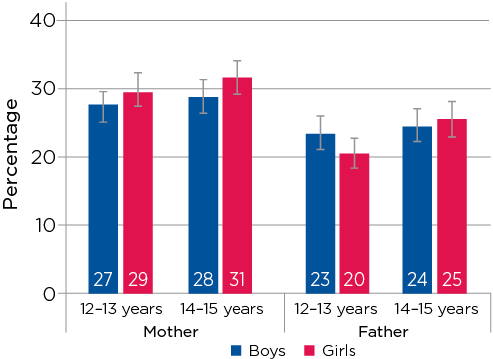

5.4 Conflict between adolescents and their parents

Rapid physical, emotional and social changes in adolescence may result in heightened conflict and diminished closeness within some parent-child relationships (Laursen & Collins, 2009). Overall, around 30% of mothers reported having at least some parent-child conflict when their child was 12–13 years old, and a similar proportion of mothers reported some conflict when their child was aged 14–15. Fathers' reports of experiencing parent-child conflict were slightly lower than those of mothers. There were no significant differences in the percentage of parents reporting some conflict, depending on the gender of the study child (Figure 5.5).

Figure 5.5: Parents' reports of at least some conflict with the study child

Notes: For conflict reported by mothers, n = 3,726 at 12–13 years and 3,266 at 14–15 years. For conflict reported by fathers, n = 2,414 at 12–13 years and 2,289 at 14–15 years.

Source: LSAC Waves 5 and 6, K cohort, weighted

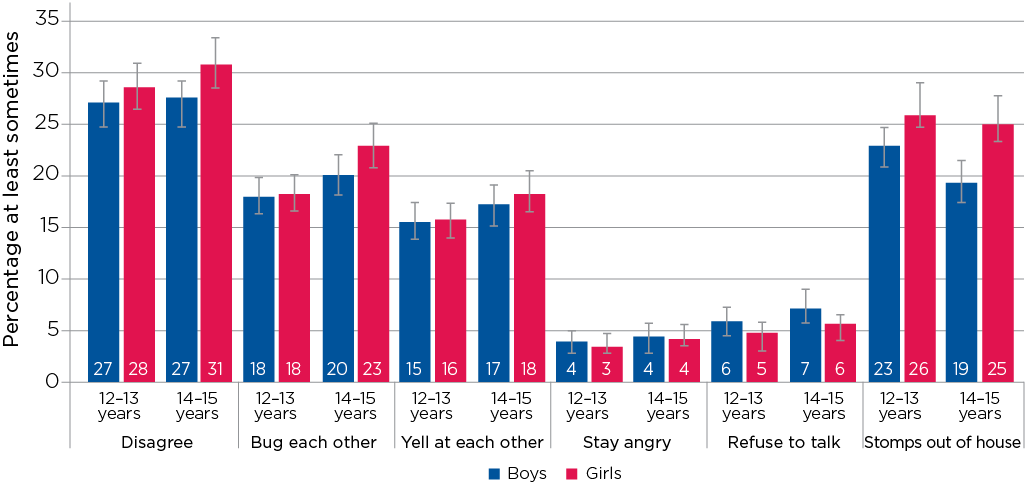

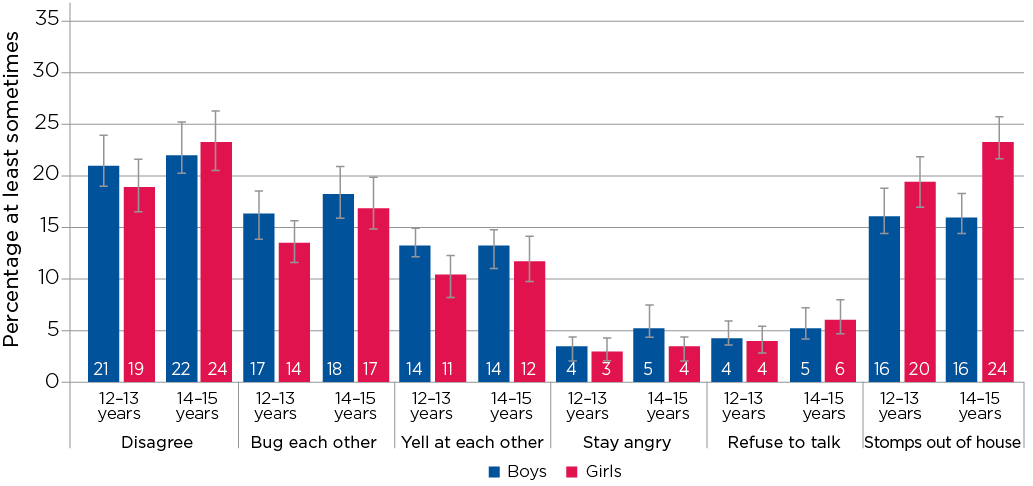

Some aspects of parent-child conflict are more prevalent than others. While 20-30% of parents say that they sometimes disagree and fight with their child, it is quite rare for parents to report that arguments with their child lead to them staying angry with each other for a very long time, or that they refuse to talk to their child (Figure 5.6 and Figure 5.7).

A higher percentage of mothers, compared to fathers, reported experiencing some conflict with their child. With the exception of mothers' reports of the study child stomping out of the house, reports of experiencing these types of conflict, at least sometimes, were slightly higher when study children were aged 14–15, compared to age 12–13.

Box 5.4: Parents' reports of conflict with their children

Parents of 12–13 and 14–15 year olds were asked about the frequency of experiencing six common situations that are indicative of conflict with the study child:

- We disagree and fight.

- We bug each other.

- We yell at each other.

- We stay angry for a very long time.

- I refuse to talk to the study child.

- The study child stomps out of the house.

Mothers and fathers responded separately using a five-point scale (1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = sometimes, 4 = pretty often, 5 = almost all the time). From these responses, average conflict scores were derived for mothers and fathers, ranging from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating more conflict between parent and child. At both time points, average conflict scores for mothers and fathers were less than 2, indicating that most parents were not experiencing a lot of conflict with their child.

For analysis of specific types of parent-child conflict, parents were considered to have experienced 'at least some' conflict with their child, if their average conflict score was 2 or higher.

For analysis of the association between parent-reported conflict and children's reports about their relationship with their parents, conflict scores were categorised as:

- no conflict (score of 1 to below 1.4)

- little conflict (scores of 1.4 to below 2)

- some conflict (scores of 2 or above).

Approximately one quarter of parents were in this 'some conflict' category.

Reports of the study child stomping out of the house as a result of parent-child conflict were more common among mothers and fathers of girls, with larger gender differences in this behaviour when study children were aged 14–15, compared to age 12–13. A quarter of mothers of girls aged 14–15 years old said that their daughter sometimes stomped out of the house, compared to 19% of mothers of boys aged 14–15 (Figure 5.6). Fathers' reports of this type of conflict were similar to those of mothers, with 24% of fathers of girls aged 14–15 years old saying that this sometimes happened, compared to only 16% of fathers of boys aged 14–15 (Figure 5.7). For other types of parent-reported conflict, there were no significant differences depending on the gender of the study child.

Figure 5.6: Mothers' reports of at least 'sometimes' experiencing specific types of conflict with their teenage child

Note: n = 3,707 at 12–13 years and 3,251 at 14–15 years.

Source: LSAC Waves 5 and 6, K cohort, weighted

Figure 5.7: Fathers' reports of at least 'sometimes' experiencing specific types of conflict with their teenage child

Note: n = 2,381 at 12–13 years and 2,252 at 14–15 years.

Source: LSAC Waves 5 and 6, K cohort, weighted

5.5 Do children's reports of relationship quality correspond to parents' reports of conflict?

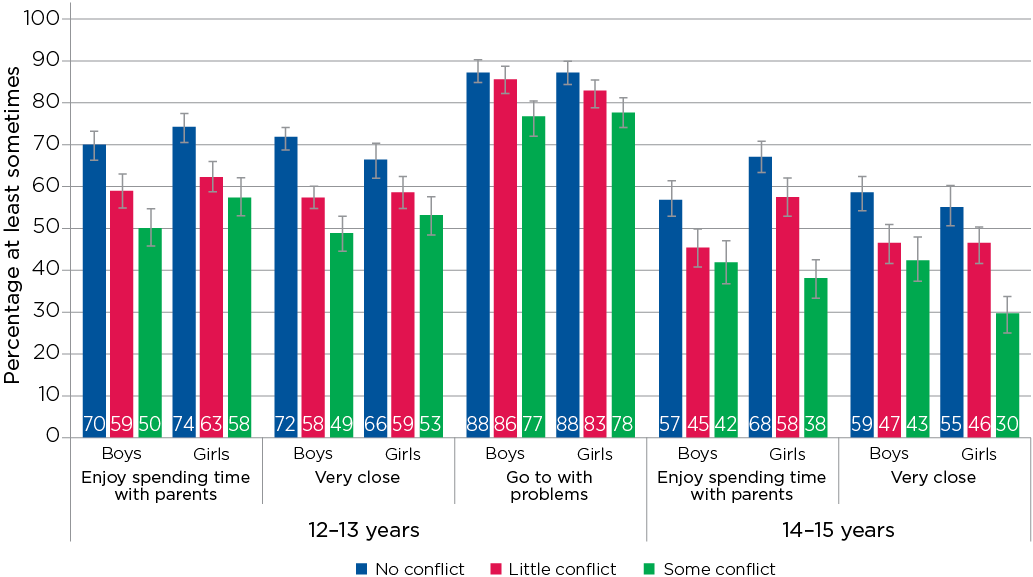

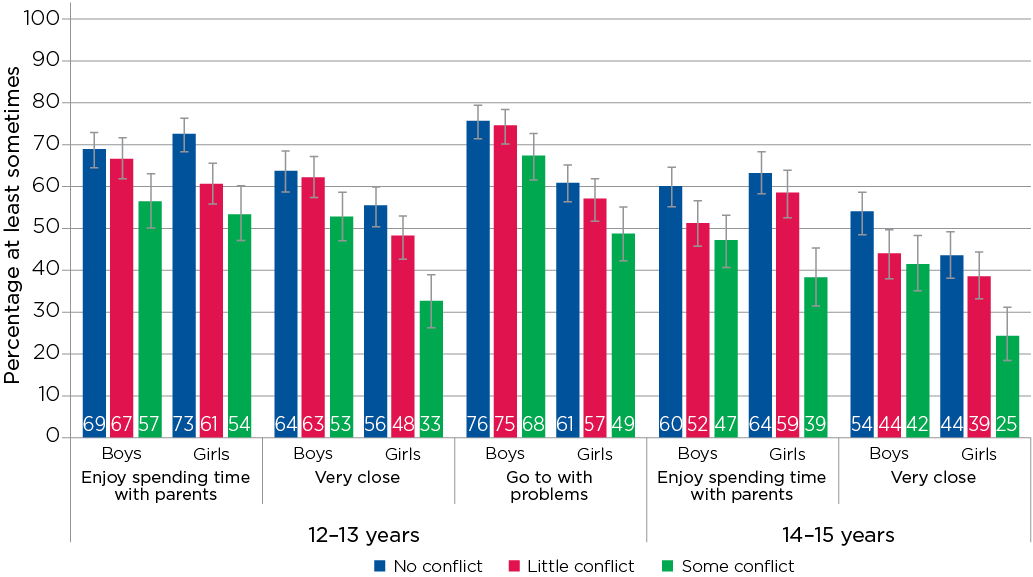

Higher levels of parent-reported conflict are related to more distance in the parent-child relationship, as indicated by children's reports. When parents report experiencing some conflict in their relationship with their child, children are less likely to enjoy spending time with their parents, less likely to feel very close to them, and less likely to go to them if they have a problem (Figures 5.8 and 5.9).2

At ages 12–13 and 14–15, the percentage of boys and girls who said that they enjoyed spending time with their mother, felt very close to their mother and would go to their mother with problems (at age 12–13) was significantly lower among those whose mother reported experiencing some conflict with the study child, compared to those whose mothers reported no conflict (Figure 5.8). For example, at age 12–13, the percentage of boys and girls who said they would go to their mother with problems, was 88% among those whose mother reported having no conflict with their child, compared to 77% of boys and 78% of girls whose mother reported having some conflict with the child.

At age 14–15, 59% of boys and 55% of girls whose mother said they had no parent-child conflict said they were very close to their mother, compared to 43% of boys and only 30% of girls whose mother reported having some conflict with the study child. The differences were more obvious among girls than boys at age 14–15. This suggests that mother-child conflict may have a stronger impact on mothers' relationships with their daughters than with their sons.

There were also significant differences in child-reported relationship quality, according to fathers' reports of conflict with the study child (Figure 5.9). For example, at age 12–13, 56% of girls and 64% of boys whose fathers reported experiencing no conflict with their child said they were very close to their father, compared to 33% of girls and 53% of boys whose father reported some conflict. At age 14–15, 64% of girls and 60% of boys whose fathers reported no conflict said they enjoyed spending time with their father, compared to only 39% of girls and 47% of boys whose father said there had been some conflict. At 12–13 and 14–15 years, these differences were more obvious among girls than boys. This suggests that, as was the case for mothers, father-child conflict may have a stronger impact on fathers' relationships with their daughters than with their sons.

Nevertheless, it is important to note that the levels of conflict parents reported were not high, even in the 'some conflict' group. It is therefore not surprising that even among parents who reported 'some conflict' with their child, high proportions of children were not distant from their parents.

In particular, it is interesting to note that at age 12–13 years, 78% of children whose mothers reported experiencing some conflict with the study child said that they would go to their mother if they had a problem. At age 12–13, there was no significant difference in the percentage of boys who said they would go to their father if they had a problem, regardless of the level of father-reported conflict. However, for girls, the percentage who said that they would go to their father with a problem was significantly lower among those whose father reported having at least some conflict with their daughter (49%, compared to 61% of girls whose father reported no conflict).

Figure 5.8: Association between mother-reported conflict and child-reported relationship quality at 12–13 and 14–15 years

Notes: n = 3,707 at 12–13 years and 2,381 at 14–15 years. 'Go to with problems' not measured at 14–15 years.

Source: LSAC Waves 5 and 6, K cohort, weighted

Figure 5.9: Association between father-reported conflict and child-reported relationship quality at 12–13 and 14–15 years

Notes: n = 3,161 at 12–13 years and 2,252 at 14–15 years. 'Go to with problems' not measured at 14–15 years.

Source: LSAC Waves 5 and 6, K cohort, weighted

5.6 Differences in the parent-child relationship, according to child and family characteristics

While most adolescents generally report positive relationships with their mother and father, some parent-child relationships appear to become more strained as children progress through the early teenage years. Fewer study children reported feelings of being very close with their parents or enjoying time with their parents when they were 14–15 years old, compared to when they were aged 12–13.

For boys, after accounting for family and child characteristics, there were no significant differences between parent-child relationships in single-parent households, compared to those living with two parents (Table 5.1).3 However, there were differences related to socio-economic position, as well as the birth order and pubertal status of the study child:

- Compared to mothers reporting on the amount of conflict they have with their eldest or only child, the odds of mothers reporting some conflict with their youngest child were reduced by around 30%.

- The odds of reporting some mother-child conflict were reduced by around 40 percentage points among mothers in the top 75% of the socio-economic position scale, compared to those in households in the lowest quartile of socio-economic position.

- Compared to 14–15 year olds in the lowest quartile of socio-economic position, the odds of boys reporting that they enjoy spending time with their father were 1.4 times higher for those in the middle 50% and 1.5 times higher for boys living in households in the top 25% of the socio-economic position scale.

- Similarly, the odds of boys reporting that they were very close to their father were 1.7 times higher for those in the highest 25% of the socio-economic position scale, compared to boys in households in the lowest 25%.

- Compared to boys who were in the early stages of puberty at age 14–15, the odds of saying that they enjoy spending time with their mother were reduced by 40 percentage points among boys in the later stages of puberty; and the odds of boys saying that they were very close to their father were reduced by a similar amount if boys were in the mid or late stages of puberty.

For girls, after taking other child and family characteristics into consideration, there were no significant differences in parent-child relationships in single-parent households, compared to those living with two parents (Table 5.2). However, compared to girls who were living with their biological father, the odds of saying they enjoy spending time with their father were reduced by around 40% among girls living with a step-father; and compared to biological fathers, the odds of reporting some conflict with their (step)daughter were 2.4 times higher among step-fathers.

At age 14–15, all girls in the LSAC sample were either in the late or post pubertal stage, and there were no significant differences in parent-child relationships, according to pubertal status. There were, however, significant differences according to birth order, language spoken at home and socio-economic status:

- The odds of girls reporting being very close to their mother are reduced by around 40 percentage points for girls who are the middle child, compared to girls who are the eldest or only child.

- Compared to girls who are the eldest or only child, the odds of saying that they enjoy spending time with their father are reduced by around 30 percentage points if they are the middle child; and the odds of reporting being very close to their father are reduced by 30-40 percentage points if they are the middle or youngest child in the family.

- Compared to girls whose parents speak a language other than English at home, the odds of reporting enjoying spending time with their father were 1.5 times higher if their parents only spoke English at home.

- The odds of reporting being very close to their mother were 1.4 to 1.6 times higher among girls in households in the top 75% of the socio-economic position scale, compared to those in the lowest 25%. Compared to girls in households in the lowest 25% of the socio-economic position scale, the odds of girls saying they enjoyed spending time with their father were 1.3 times higher among those in the middle 50% of socio-economic position.

Notes: Odds ratios based on logistic regressions. 'Single parent' includes single mothers when exploring child relationships with mothers, and single fathers when exploring child relationships with fathers. Statistically significant associations are noted: * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

Source: LSAC Wave 6, K cohort, weighted

Notes: Odds ratios based on logistic regressions. 'Single parent' includes single mothers when exploring child relationships with mothers, and single fathers when exploring child relationships with fathers. At age 14–15, all girls were either in the late or post pubertal stages. Statistically significant associations are noted: * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

Source: LSAC Wave 6, K cohort, weighted

Summary

As children grow into adolescence, parent-child relationships change. Young people increasingly seek independence from their parents, as relationships with others take on more importance. Despite these changes, parents usually remain integral to their children's lives (Steinberg & Silk, 2002).

Consistent with other research (Laursen & Collins, 2009), we find that most young people held positive views about their relationships with their (co-resident) mothers and fathers, based on their feelings of closeness to them and their reports of enjoying time with them and going to them with problems. However, the quality of parent-child relationships decreased slightly over time; and these patterns varied slightly by gender of parent and child.

Early adolescence has been shown to be a time of increased emotional and physical distancing from parents, and one in which increases in conflict are apparent (Steinberg, 2001). However, we find relatively low levels of conflict between mothers and children and fathers and children. Overall reports of parent-child conflict when children were 10–11 were similar to those at age 12–13. At both time points, reports of conflict between mothers and their children were more common than reports of father-child conflict.

There were clear associations between child-reported measures of parent-child relationship quality and the parent-reported conflict measure. When the parents reported having little or no conflict with their children, children were significantly more likely to report enjoying spending time with their parents, feeling very close to their parents and going to their parents with problems.

The factors associated with parent-child relationship quality at age 14–15 differed depending on the gender of the study child. For girls, but not for boys, reports of relationships with fathers were less positive if they were describing their relationship with their step-father, rather than their biological father; and step-fathers were more likely than biological fathers to report having some conflict with daughters. For boys, pubertal status was an important factor, with boys in the later stages of puberty less commonly reporting enjoying time with their mother or being very close to their father, compared to boys in the earlier stages of puberty.

For girls and boys, reports of parent-child relationship quality were more positive among those in households at the higher end of the socio-economic scale, compared to those in the lowest quartile. These differences are likely to be at least partly due to differences in the types of activities that parents and children do together, with those at the higher end of the socio-economic scale able to afford a wider range of leisure activities.

However, it is important to note that we have not looked at all key family characteristics that may make a difference to parent-child relationships; in particular, we have not taken account of the harmony or quality of other relationships within the household. If parents themselves are in conflict, this may have implications for parenting and for their relationships with their children. Other factors that may influence family functioning and parent-child relationships include the physical and mental health of family members, financial stress and other stressful life events that may have occurred within the family.

In addition, this chapter has focused only on parent-child relationships within the household of the children's primary carer. Some adolescents have more complex parental relationships, with parents living in two households. LSAC collects information about these relationships from the study children and, potentially, the parents living in another household, which could fill out this picture. These young people may face additional challenges in negotiating high quality parental relationships.

References

Fosco, G. M., Stormshak, E. A., Dishion, T. J., & Winter, C. E. (2012). Family relationships and parental monitoring during middle school as predictors of early adolescent problem behavior. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 41(2), 202-213.

Hill, N. E., Bromell, L., Tyson, D. F., & Flint, R. (2007). Developmental commentary: Ecological perspectives on parental influences during adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 36(3), 367-377.

Hoeve, M., Dubas, J. S., Eichelsheim, V. I., van der Laan, P. H., Smeenk, W., & Gerris, J. R. (2009). The relationship between parenting and delinquency: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(6), 749-775.

Laursen, B., & Collins, W. A. (2009). Parent-child relationships during adolescence. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology: Contextual influences on adolescent development (pp. 3-42). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Smart, D., Sanson, A., & Toumbourou, J. (2008). How Do parents and teenagers get along together?: Views of young people and their parents. Family Matters, 78, 18-27.

Steinberg, L. (2001). We know some things: Parent-adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 11(1), 1-19.

Steinberg, L., & Silk, J. S. (2002). Parenting adolescents. In M. H. Bornstein, Handbook of parenting: Volume 1. Children and Parenting (pp. 103-133). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

1 Within the primary carer household there are single as well as couple parents, and biological as well as step-parents. Around 15% of the mothers are single mothers while only 2% of the fathers are single fathers. Most mothers and fathers are biological parents (99% of mothers and 94% of fathers).

2 For mother-child relationships and father-child relationships, the associations between child and parents' reports are statistically significant at the 5% level.

3 At age 14–15, very few children were living with a mother who was not their biological mother. For boys, there were no significant differences in relationships with step-parents (step-mothers or step-fathers), compared to biological parents.

Acknowledgements

Featured image: © GettyImages/golero