10. Adolescents’ resilience

10. Adolescents’ resilience

In the course of growing up, young Australians are likely to experience difficult circumstances and stressful life events. For adolescents, these difficult circumstances can include everyday challenges such as arguments with friends, sporting losses or disappointments with test results. More serious problems commonly encountered are family breakdown, illnesses or deaths of family members or friends, or being the victim of bullying. The ability to recover or 'bounce back' from setbacks, adapt to difficult circumstances that cannot be changed, and learn and grow from such experiences is termed 'resilience' (Connor & Davidson, 2003; Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000; Masten, 2014; Rutter, 2006). Resilience is an important skill for navigating life's ups and downs, which would be beneficial to enhance in young people, as there are concerns that resilience in young Australians is in decline (Orygen, 2017).

Research suggests that a person's resilience is determined by a variety of factors, including individual, biological and psychological characteristics, relationships with family and peers, and environmental influences such as those in the school and broader community (VicHealth, 2015b). Throughout their lives, children and adolescents might have different vulnerabilities and protective systems affecting their resilience. For example, adolescents may be particularly vulnerable to stresses relating to family, friends and schools (Wright & Masten, 2005). Significant changes in social environments in late adolescence and the transition to adulthood - including employment, tertiary education and/or leaving the family home - may also affect resilience (Burt & Paysnick, 2012; Masten et al., 2004).

Resilience can change as individuals interact with and respond to people in their lives and their environments. This creates opportunities to promote resilience in young people in different settings (Masten, 2009). This chapter explores levels of self-reported resilience at age 16-17 years and examines whether resilience differs according to characteristics of the individual and their family, peer and school environments. The insights in this chapter may help us to understand which aspects of adolescents' lives are related to their resilience and how policy and practice interventions can be designed to help prepare adolescents for the transition into adulthood.

10.1 How resilient are teenagers?

There are many different aspects to resilience, including the ability to cope and adapt with changes and challenges, the capacity to deal and persist with problems without being overwhelmed, and self-belief in one's ability to deal with obstacles (see Box 10.1).

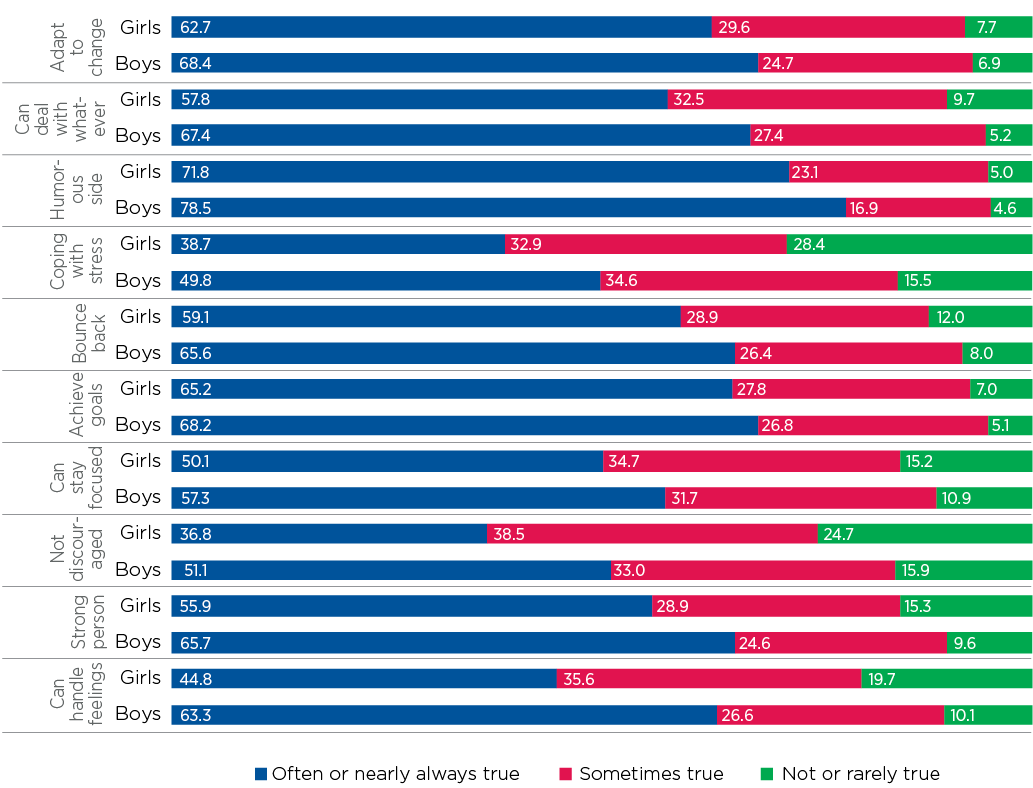

Of all the resilience statements, boys and girls at 16-17 years old rated trying to see the humourous side of things most highly, reflecting a common ability to use humour when faced with problems (Figure 10.1). However, fewer boys and girls felt that coping with stress strengthened them or that they were not easily discouraged by failure. This suggests that many young people do not feel that they can persist when faced with adversity.

Overall, a significantly greater proportion of boys than girls reported higher levels of resilience, saying that they often (or nearly always) displayed characteristics related to being resilient. For example:

- Fifty-one per cent of boys and 37% of girls said that they were not easily discouraged by failure.

- Sixty-three per cent of boys and 45% of girls said that they can usually handle unpleasant feelings.

- Fifty per cent of boys and 39% of girls responded 'often or nearly always true' to the statement 'coping with stress can strengthen me'.

- Sixty-seven per cent of boys and 58% of girls felt that they could (often or always) deal with whatever comes.

On average, the total resilience score for adolescents was 26.5 out of 40.1 This suggests that the 'average' 16-17 year old views themselves as displaying resilient characteristics 'often'. Boys had significantly higher resilience scores than girls - 27.6 out of 40 for boys compared to 25.5 for girls.2

Box 10.1: Resilience measures in LSAC

At age 16-17 (Wave 7), the LSAC K cohort reported for the first time on their perceptions of their resilience. This was measured using the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10) (Campbell-Sills & Stein, 2007). Study adolescents were asked to consider how true the following statements were for them in the past month:

- Able to adapt to change

- Can deal with whatever comes

- Tries to see the humorous side of things

- Coping with stress can strengthen me

- Tend to bounce back after illness or hardship

- Can achieve goals despite obstacles

- Can stay focused under pressure

- Not easily discouraged by failure

- Thinks of self as strong person

- Can handle unpleasant feelings.

They could choose from 'Not true at all' (scored 1), 'Rarely true' (2), 'Sometimes true' (3), 'Often true' (4) and 'True nearly all of the time' (5). If a particular situation had not occurred recently, participants were instructed to answer according to how they think they would have felt.

A total resilience score was created by summing the response score of all 10 items (recoded 0-4). The possible range for the resilience scale was therefore 0-40, with higher scores indicating higher levels of resilience.

Figure 10.1: Percentage of 16-17 year olds reporting aspects of resilience, by gender

Notes: With the exception of 'achieve goals', differences for girls and boys were significant at the 5% level (determined by non-overlapping 95% confidence intervals). n = 1,445 for girls and 1,483 for boys.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Wave 7, weighted

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Higher levels of resilience among boys have been seen in other population studies that have measured resilience in the same way (Campbell-Sills, Forde, & Stein, 2009; VicHealth, 2015a). While it is possible that this may be due to reporting bias, with males perhaps being more likely to appear strong in the face of stress, other studies that have measured resilience in different ways have also shown significantly higher levels of resilience in males (Bonanno, Galea, Bucciarelli, & Vlahov, 2007). The finding that, on average, girls report lower levels of resilience than boys, is also in line with the observation that females have higher rates of psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety and phobias, which may have a stress-related component (Craske, 2003).

10.2 Personality and resilience

Personality traits may be related to successfully coping with negative or stressful life events (Box 10.2). For example, young people with high levels of neuroticism - which includes traits such as anxiety, insecurity, self-doubt, short temper and instability - may be more susceptible to stress and negative emotions, and so have lower resilience (Campbell-Sills et al., 2009).

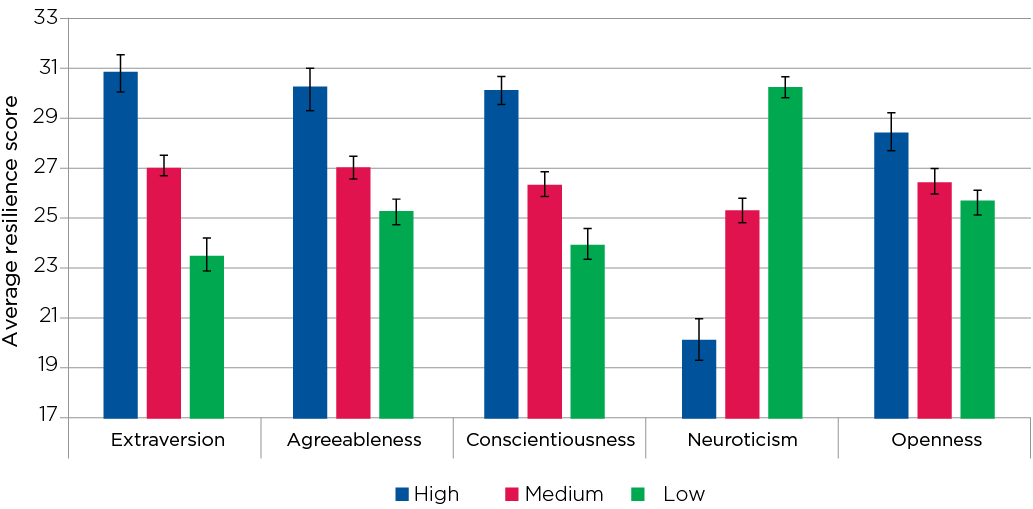

For 16-17 year olds, there were large differences in average levels of resilience according to each of the Big 5 personality traits (Figure 10.2).

Box 10.2: Big 5 personality traits

Personality traits were measured in the LSAC K cohort at Wave 7 using the Big 5 Personality Inventory, (BFI-10) (Rammstedt & John, 2007). Adolescents were asked to rate how well the following 10 statements described their personality on a five-point scale from '1 = disagree strongly' to '5 = agree strongly':

1. Extraversion

- I see myself as someone who is reserved; keeps thoughts and feelings to self. (reversed)

- I see myself as someone who is outgoing, sociable.

2. Agreeableness

- I see myself as someone who is generally trusting.

- I see myself as someone who tends to find fault with others. (reversed)

3. Conscientiousness

- I see myself as someone who tends to be lazy. (reversed)

- I see myself as someone who does things carefully and completely.

4. Neuroticism

- I see myself as someone who is relaxed, handles stress well. (reversed)

- I see myself as someone who gets nervous easily.

5. Openness

- I see myself as someone who doesn't like artistic things (plays, music). (reversed)

- I see myself as someone who has an active imagination.

For each of the five personality traits, the average of the two items formed a scale ranging from 1 to 5. Each of the personality traits was then classified as High (top 25%), Medium (middle 50%) or Low (lowest 25%).

Figure 10.2: Average resilience scores, by Big 5 personality traits

Notes: 95% confidence intervals are shown by the 'I' bars at the top of each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the values are significantly different. n = 2,933.

Source: LSAC Wave 7, K cohort, weighted

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

On average, higher levels of extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness and openness were associated with higher resilience scores. However, those with higher levels of neuroticism had lower resilience scores - 16-17 year olds with high levels of neuroticism had average resilience scores that were 10 points (approximately 1.5 SD) lower than those with low levels of neuroticism (Figure 10.2). It is possible that this relationship may partly account for the observation that girls report lower levels of resilience than boys. Females consistently report higher levels of neuroticism than males (Schmitt, Realo, Voracek, & Allik, 2008) and the LSAC data show that at age 16-17, 19% of females were high in neuroticism, compared to 7% of boys.

These findings, which have also been observed in many other studies (Oshio, Taku, Hirano, & Saeed, 2018), support the idea that the main elements of resilience include a higher level of self-control and motivation towards accomplishments, a higher level of positive emotions and engagement with social activity, and a higher level of emotional stability or lower level of negative emotions.

10.3 Parent-child relationships and resilience

Close relationships between adolescents and their parents are known to promote and support positive development (Masten, 2018; Masten & Shaffer, 2006). Even though adolescents become less dependent on their parents as they grow, their relationship with their parents continues to be a major influence in their lives (Collins & Roisman, 2006; Smart, Sanson, & Toumbourou, 2008). Stable and supportive parent-child relationships can be protective in helping adolescents deal with stress and challenges (Bowes, Maughan, Caspi, Moffitt, & Arseneault, 2010; Garmezy, 1985). Growing up in a family environment characterised by instability, conflict or neglect has a well-documented negative effect on adolescent development and may compromise resilience (Walper & Beckh, 2006).

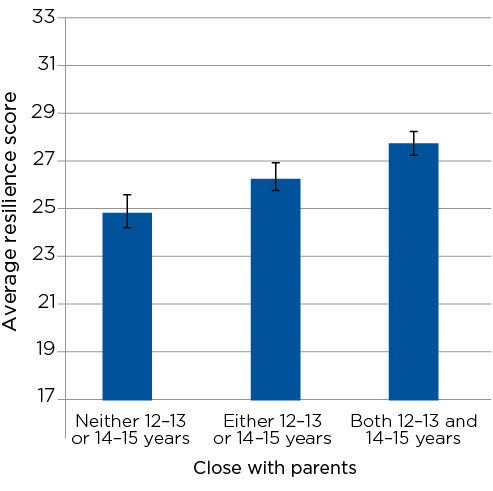

Using the same data, another study has shown that the proportion of adolescents reporting feeling 'very close' to mothers and fathers decreased between ages 12-13 and 14-15 (Yu & Baxter, 2018). When considering how many of the 16-17 year olds had been 'very close' with one or both parents when they were 12-13 and 14-15 years of age, approximately half reported very close relationships at both ages, 29% had been very close at one age only and 22% had not been very close at either age. Teenagers' resilience levels differed depending on their relationship with their parents in early and mid-adolescence (ages 12-13 and 14-15). On average, teenagers who reported having a very close relationship with one or both of their parents during early and mid-adolescence had higher levels of resilience at age 16-17 (by almost 3 points, approximately 0.5 SD) compared to those who were not close to their parents at either age (Figure 10.3).

Box 10.3: Closeness with parents

At ages 12-13 and 14-15, the LSAC study children were asked:

- 'How close do you feel to your mum?'

- 'How close do you feel to your dad?'

with the following response options: 'very close', 'quite close', 'not very close', and 'not close at all'.

At each age, children were rated as 'very close with at least one parent' if they responded 'very close' to either mum or dad or both.

These questions were adapted from the Adolescent Survey of the Longitudinal Study of Separated Families (Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2009).

Figure 10.3: Average resilience scores, by closeness with parents at 12-13 and 14-15 years

Notes: 95% confidence intervals are shown by the 'I' bars at the top of each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the values are significantly different. n = 2,542.

Source: LSAC Waves 5-7, K cohort, weighted

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Box 10.4: Parent-child conflict

Parent-child conflict was assessed based on parent responses to a series of questions about different types of conflict when their child was aged 12-13 (Wave 5) and 14-15 (Wave 6). Mothers and fathers responded separately on how often they experienced the following situations on a five-point scale (1 = 'not at all', 2 = 'a little', 3 = 'sometimes', 4 = 'pretty often', 5 = 'almost all the time'):

- We disagree and fight.

- We bug each other.

- We yell at each other.

- We stay angry for a very long time.

- I refuse to talk to the study child.

- The study child stomps out of the house.

These items were adapted from the Canadian National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (NLSCY) (Statistics Canada, 2000)

From these responses, average parent conflict scores were derived, ranging from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating higher frequency of parent-child conflict. Parents were considered to have experienced no conflict if their average conflict score was less than 2 and to have experienced 'at least some' conflict if their scores were 2 or higher.

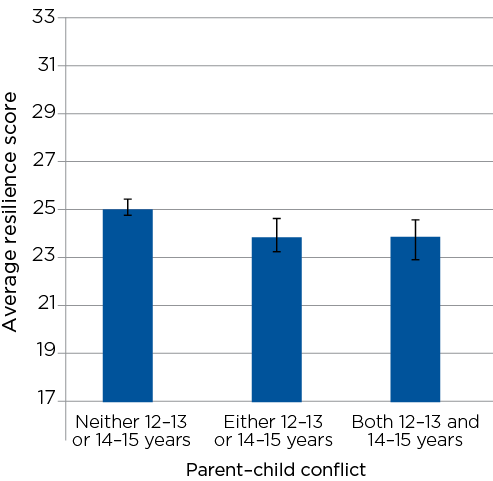

Adolescence can often be a time of increased parent-child conflict as adolescents develop their own identity and assert their independence from their parents. While a certain level of conflict might be considered normal during this period, high levels of conflict can have a negative effect on adolescents' psychological development (Steinberg, 2001). Based on parents' reports of parent-child conflict when the study child was aged 12-13 and 14-15, approximately 19% of 16-17 year olds had been exposed to parent-child conflict at one age only and 13% had experienced parent-child conflict at both ages. Two thirds of parents (67%) reported that they had not experienced conflict with their child when they were 12-13 or 14-15 years old.

On average, resilience scores were higher (1.6 points or 0.2 SD) among 16-17 year olds whose parents did not report any conflict, compared to those experiencing conflict in one or two waves (Figure 10.4). There was no difference in resilience scores between adolescents whose parents reported conflict at just one wave or at both, suggesting that any conflict, even non-sustained or episodic parent-child conflict, may be damaging to adolescent resilience.

Figure 10.4: Average resilience scores, by parent-child conflict at 12-13 and 14-15 years

Notes: 95% confidence intervals are shown by the 'I' bars at the top of each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the values are significantly different. n = 2,608.

Source: LSAC Waves 5-7, K cohort, weighted

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

10.4 Family factors and resilience

Family factors beyond the parent-child relationship, such as family structure and demographic characteristics, may also influence adolescents' resilience. For example, socio-economic disadvantage has been associated with lower resilience in adults (Campbell-Sills et al., 2009).

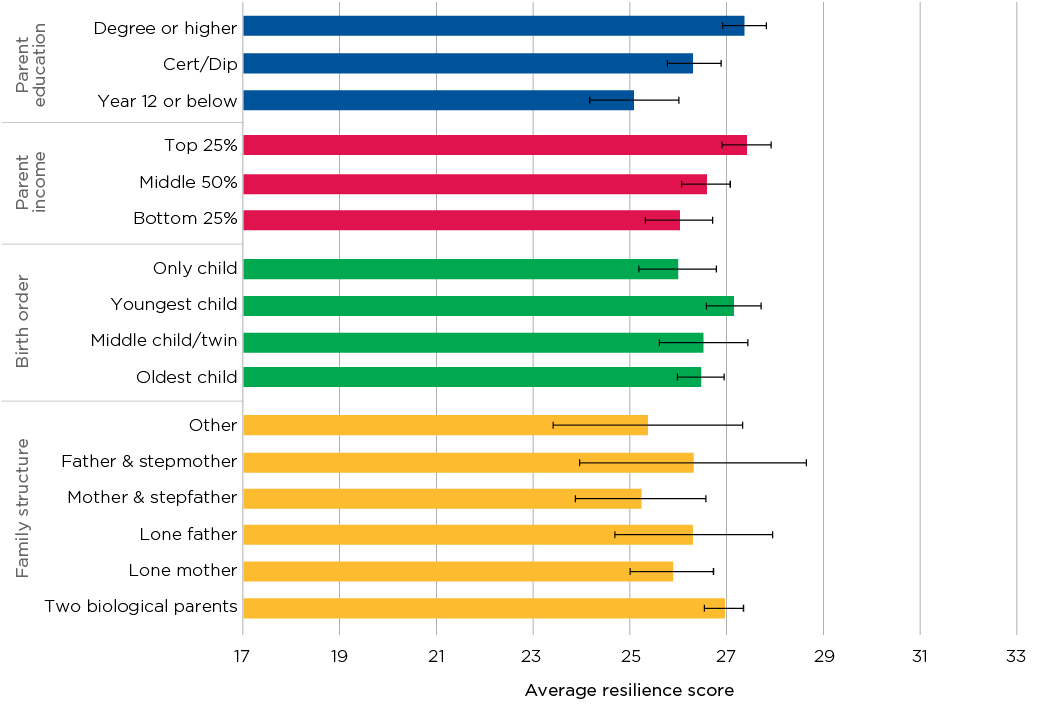

Average resilience scores differed depending on family characteristics such as family structure, birth order, parents' combined income and parents' education levels (Figure 10.5). However, these differences were not as large as those related to parent-child closeness (Figure 10.3). Compared to 16-17 year olds whose parents' income was in the top 25%, those whose parents' income was in the lowest quarter had resilience scores that were, on average, over 1.4 points (0.2 SD) lower (Figure 10.5). Resilience also differed by parents' education levels, with those whose parents had a degree or higher having resilience scores that were 2.3 points (0.3 SD) higher than those with parents whose highest level of education was Year 12 or below. It is likely that higher levels of parent education and income provide cognitive and material resources that help to lower stress and increase resilience in adolescents (Campbell-Sills et al., 2009).3

While parental separation can be a stressful and even traumatic experience affecting resilience (Schaan & Vögele, 2016), average resilience scores did not differ greatly between adolescents in different family types. There were no significant differences in average resilience scores among 16-17 year olds in single-parent households and those living with both their biological parents, though average resilience scores for those who were living with their mother and a stepfather were 1.8 points (0.25 standard deviations) lower than those living with both biological parents.

There has been some anecdotal evidence to suggest that levels of resilience may differ depending on birth order, with middle children being more flexible and resilient than other children (Adler, 1964; Grose, 2003); however, the LSAC data show no significant differences in average levels of resilience at the age of 16-17 according to birth order. It is possible that certain characteristics typically found in first-born children (persistence and self-efficacy) and youngest or only children (affability and positive outlook) contribute to resilience in different but positive ways.

Figure 10.5: Average resilience scores, by family demographic factors

Notes: 95% confidence intervals are shown by the 'I' bars at the top of each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the values are significantly different. n = 2,893 for birth order and family structure; n = 2,876 for parent income; n = 2,803 for parent education.

Source: LSAC Wave 7, K cohort, weighted

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Family support refers to having people in your immediate or extended family who you trust when you want to talk about things that upset or worry you. At ages 10-11 and 12-13, LSAC study children were asked who they would talk to if they had a problem (Box 10.5).

Box 10.5: Family support

At ages 10-11 and 12-13, LSAC study children were asked, 'If you had a problem, who would you talk to about it?' They were given a list of possible people including their mother, their father, a sibling and other relatives. They could choose as many people as they liked from the list (Gray & Daraganova, 2018).

Study children were classified as having no family support if they responded 'no' to all four family options (mother, father, sibling and other relative).

A significant minority of approximately 16% of young people who had a lack of family support; that is, have not had people in their immediate or extended family who they trusted when they wanted to talk about things that made them upset or worried them consistently through their early adolescent years (10-13 years old), reported lower resilience levels at age 16-17. The average resilience score at age 16-17 for this group who lacked family support in early or mid-adolescence was 25.3 (95% CI: 24.4 - 26.2), approximately 0.2 SD lower than for those who had support at one or both ages 26.8 (95% CI: 26.4 - 27.2).

10.5 Peer relationships and resilience

Peer relationships are very important in adolescence. During this time, adolescents develop autonomy from their parents and increasingly turn to their peers for social interaction, advice and support (del Valle, Bravo, & Lopez, 2010).

Box 10.6: Good friendships

Having at least one good friend was measured at age 16-17 using an item from the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) Peer Problems subscale (Goodman, 1997), in which adolescents rated their agreement to the statement, 'I have one good friend or more', on a scale of '1 = Not true', '2 = Somewhat true' and '3 = Certainly true'. Approximately 84% of 16-17 year olds indicated they had at least one good friend by responding 'Certainly true'.

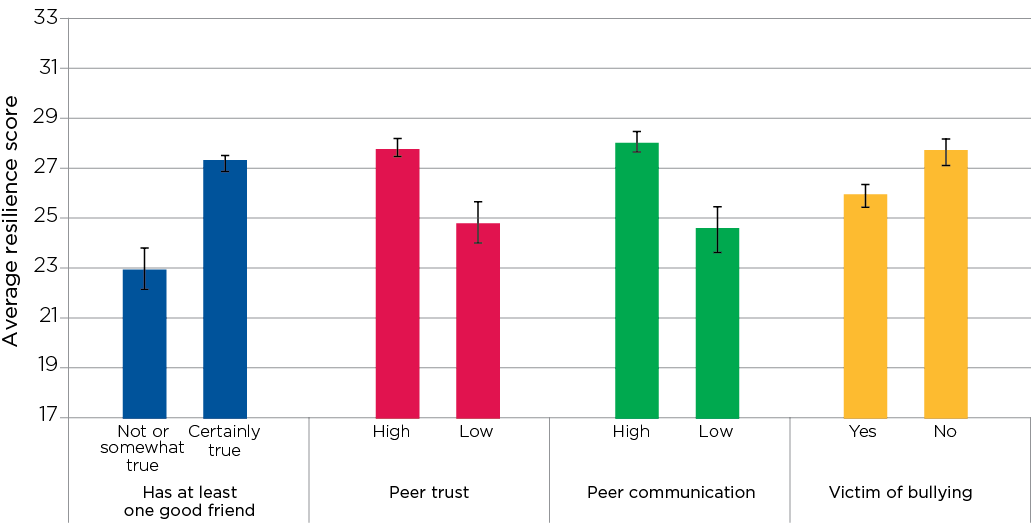

Figure 10.6: Resilience levels were higher among 16-17 year olds with at least one good friend

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Box 10.7: Peer relationships

The quality of peer attachments was measured in LSAC using the Peer Trust and Peer Communication subscales of the Peer Attachment Scale of the Inventory of Peer and Parental Attachment (Gullone & Robinson, 2005).

- Trust reflects the degree of mutual understanding and respect between peers. Adolescents rated how well four statements such as 'I feel my friends are good friends' and 'I trust my friends' reflect their peer relationships on a five-point scale from '1 = Almost always true' to '5 = Almost never true'.

High peer trust was indicated by a mean scale score lower than one standard deviation below the LSAC sample mean. At age 16-17, approximately 58% reported high peer trust.

- Communication reflects the extent and quality of communication in peer relationships. Adolescents rated how well four statements such as 'My friends sense when I'm upset about something' and 'My friends encourage me to talk about my difficulties' reflect their peer relationships on the same five-point scale as for the trust sub-scale.

Good peer communication was indicated by a mean scale score lower than one standard deviation below the LSAC sample mean. At age 16-17, approximately 58% reported good peer communication.

Figure 10.7: Average resilience scores, by peer relationships

Notes: See Boxes 10.6, 10.7 and 10.8 for descriptions of measures. 95% confidence intervals are shown by the 'I' bars at the top of each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the values are significantly different.

n = 2,925 for peer trust and peer communication; 2,934 for has at least one good friend and victim of bullying.

Source: LSAC Wave 7, K cohort, weighted

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

At age 16-17 (see Figure 10.7), average resilience scores were higher for young people who had:

- At least one good friend - average resilience scores were over 4 points (0.6 SD) higher than for those who did not have at least one good friend.

- High levels of trust in their friends - average resilience scores were 3 points (0.4 SD) higher than for those with low levels of trust in their friends.

- Good communication with their friends - average resilience scores were 3.5 points higher (0.5 SD), compared to those who reported poorer communication with their friends.

These results highlight the potential vulnerability of adolescents who do not have a close friend, or friends that they trust to talk with about any difficulties they may be facing. While positive relationships with peers can be a support for building resilience, the experience of being a victim of bullying can damage resilience (Box 10.8). Compared to those who had not experienced any form of bullying in the previous 12 months, those who had been the victim of some form of bullying had average resilience scores almost 2 points (0.25 SD) lower (Figure 10.7). This highlights the insidious nature of bullying and its potential to undermine mental health in the longer term (Vassallo, Edwards, Renda, & Olsson, 2014).

Box 10.8: Bullying

Bullying has been defined as intentional and repeated aggressive behaviour towards a peer that causes them harm (Smith et al., 1999). At age 16-17, LSAC study children were asked if they had experienced any of nine bullying behaviours such as 'someone hit or kicked me on purpose' and 'someone said mean things to me or called me names' in the past year (Brockenbrough, Cornell, & Loper, 2002). Teenagers were considered to have been the victim of bullying if they reported experiencing any act of bullying in the previous last 12 months. At age 16-17, approximately 58% indicated that they had been a victim of bullying.

10.6. School belonging and resilience

Adolescents spend a large part of their lives at school, making it a very important social environment. It is where many of the peer interactions that affect resilience occur and it can play a key role in supporting young people.

Positive interactions with teachers and a feeling of being valued and supported at school may strengthen resilience, especially for adolescents who may show particular personality traits or lack family support (Tiet et al., 2010).

Box 10.9: School belonging

School belonging was measured in the LSAC study using the Psychological Sense of School Membership (PSSM) scale (Goodenow, 1993). This scale measures the extent to which students feel personally accepted, respected, included and supported by others in the school social environment. Students were asked to rate how true the following statements were for them on a five-point scale, ranging from 1 'not true at all' to 5 'completely true':

1.People here notice when I'm good at something.

2.It is hard for people like me to be accepted here.

3.Other students in this school take my opinions seriously.

4.Most teachers at this school are interested in me.

5.Sometimes I don't feel as if I belong here.

6.There's at least one teacher or other adult in this school I can talk to if I have a problem.

7.Teachers here are not interested in people like me.

8.I am included in lots of activities at this school.

9.I can really be myself at this school.

10.The teachers here respect me.

11.I wish I were in a different school.

12.Other students here like me the way I am.

A total score for school belonging was created by summing the score for all 12 items (items 2, 5, 7 and 11 were reverse coded). The scale score had a possible range of 12 (lowest school belonging) to 60 (highest school belonging). School belonging was classified as 'high' (top third of scores), 'medium' (middle third of scores) or 'low' (lowest third of scores).

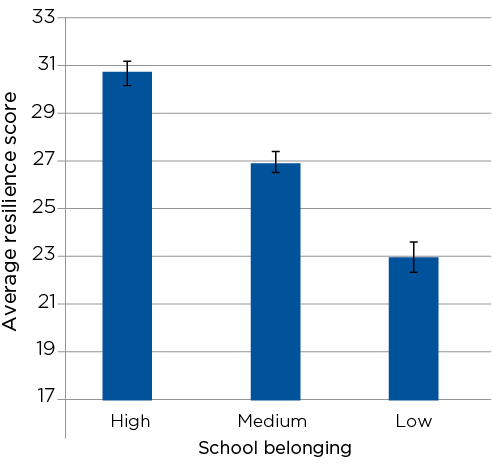

At age 16-17, there were large differences in average resilience scores according to the level of school belonging that young people reported (Box 10.9). Resilience was highest among those who reported a high level of school belonging - around 4 points (0.6 SD) higher than for those with medium levels of school belonging and 7 points (1 SD) higher than for those who reported low levels of school belonging (Figure 10.8).

Figure 10.8: Average resilience scores at age 16-17, by levels of school belonging

Notes: 95% confidence intervals are shown by the 'I' bars at the top of each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the values are significantly different. n = 2,532.

Source: LSAC Wave 7, K cohort, weighted

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

These results confirm that, in general, the school environment, including relationships with teachers, is related to adolescents' resilience. It is not possible to know from these data if there is a direct causal relationship between school belonging and resilience, or whether another factor (e.g. depressive symptoms) is related to both school belonging and resilience. However, it is likely that a strong sense of belonging at school is especially important for adolescents from unstable or unsupportive families, and/or those with certain types of personality; for example, young people with higher levels of neuroticism who may be at risk of lower resilience.

Summary

This chapter has provided a snapshot of self-reported resilience among Australian 16-17 year olds. Resilience levels were related to individual characteristics, such as gender and personality. On average, males reported higher levels of resilience than females and young people with outgoing, conscientious, agreeable and emotionally stable personality traits reported higher levels of resilience. Young people with positive and supportive relationships with their parents and friends were shown to have significantly higher levels of resilience; and those who reported higher levels of school engagement also reported higher levels of resilience. This suggests that supports for teenagers in their family, peer and school networks may serve as opportunities for youth health and wellbeing policy and interventions.

The findings in this chapter raise suggestions for further research. Further analyses using longitudinal data will allow researchers and practitioners to understand how individual, family, peer, school and community factors act together over time to influence resilience. In this chapter resilience has been conceptualised as a character trait, measured by self-rating of resilience competencies. Broader concepts of resilience as a process of adaptation involve consideration and measurement of the internal and external resources available to an individual (Olsson, Bond, Burns, Vella-Brodrick, & Sawyer, 2003). These include those provided by family, friends or school as described in this chapter. Use of LSAC data to measure this form of resilience in young people will provide comprehensive guidance for policy makers as they assess who is at risk of low resilience and where interventions might best be targeted.

In addition, follow-up of the LSAC cohort at older ages will reveal how the self-rated measure of resilience examined in this chapter relates to more objective measures of resilience, such as coping with actual stressful life events as they arise. It will also allow researchers to study the effect of high versus low resilience in late adolescence on later life outcomes, such as employment, relationships, mental and physical health. A better understanding of resilience, along with its causes and effects on life outcomes, will help parents, teachers and others wishing to foster resilience in young people.

References

Adler, A. (1964). Problems of neurosis. Oxford: Harper Torchbooks.

Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS). (2009). The longitudinal study of separated families. Melbourne: AIFS. Retrieved from aifs.gov.au/family-pathways

Balluerka, N., Gorostiaga, A., Alonso-Arbiol, I., & Aritzeta, A. (2016). Peer attachment and class emotional intelligence as predictors of adolescents' psychological well-being: A multilevel approach. Journal of Adolescence, 53, 1-9.

Becker, G. S., & Tomes, N. (1986). Human capital and the rise and fall of families. Journal of Labor Economics, 4(3), S1-S39.

Bonanno, G. A., Galea, S., Bucciarelli, A., & Vlahov, D. (2007). What predicts psychological resilience after disaster? The role of demographics, resources, and life stress. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(5), 671-682.

Bowes, L., Maughan, B., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., & Arseneault, L. (2010). Families promote emotional and behavioural resilience to bullying: Evidence of an environmental effect. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(7), 809-817.

Brockenbrough, K. K., Cornell, D. G., & Loper, A. B. (2002). Aggressive attitudes among victims of violence at school. Education and Treatment of Children, 25(3), 273-287.

Burt, K. B., & Paysnick, A. A. (2012). Resilience in the transition to adulthood. Development and Psychopathology, 24(2), 493-505.

Campbell-Sills, L., Forde, D. R., & Stein, M. B. (2009). Demographic and childhood environmental predictors of resilience in a community sample. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43, 1007-1012.

Campbell-Sills, L., & Stein, M. B. (2007). Psychometric analysis and refinement of The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20(6), 1019-1028.

Collins, W. A., & Roisman, G. I. (2006). The influence of family and peer relationships in the development of competence during adolescence. In A. Clarke-Stewart, & J. Dunn (Eds.), Families count: Effects on child and adolescent development. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. T. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76-82.

Craske, M. G. (2003). Origins of phobias and anxiety disorders: Why more women than men? Oxford, UK: Pergamon.

del Valle, J. F., Bravo, A., & Lopez, M. (2010). Parents and peers as providers of support in adolescents social network: A developmental perspective. Journal of Community Psychology, 38(1), 16-27.

Garmezy, N. (Ed.). (1985). Stress resistant children: The search for protective factors. Oxford England: Pergamon Press.

Goodenow, C. (1993). The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents - scale development and educational correlates. Psychology in the Schools, 30(1), 79-90.

Goodman, R. (1997). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 38(5), 581-6.

Gorrese, A. (2016). Peer attachment and youth internalizing problems: A meta-analysis. Child & Youth Care Forum, 45(2), 177-204.

Gray, S., & Daraganova, G. (2018). Adolescent help-seeking. In Australian Institute of Family Studies (Eds.), Growing up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children, Annual Statistical Report 2017. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Grose, M. (2003). Why first borns rule the world and last borns want to change it. North Sydney, Australia: Random House Australia.

Gullone, E., & Robinson, K. (2005). The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment - Revised (IPPA-R) for children: A psychometric investigation. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 12(1), 67-79.

Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D., & Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71(3), 543-562.

Masten, A. S. (2009). Ordinary magic: Lessons from research on resilience in human development. Education Canada, 49, 28-32.

Masten, A. S. (2014). Global perspectives on resilience in children and youth. Child Development, 85(1), 6-20.

Masten, A. S. (2018). Resilience theory and research on children and families: Past, present, and promise. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 10(1), 12-31.

Masten, A. S., Burt, K. B., Roisman, G. I., Obradovic, J., Long, J. D., & Tellegen, A. (2004). Resources and resilience in the transition to adulthood: Continuity and change. Development and Psychopathology, 16(4), 1071-1094.

Masten, A. S., & Shaffer, A. (2006). How families matter in child development: Reflections from research on risk and resilience. In A. Clarke-Stewart, & J. Dunn (Eds.), Families count: Effects on child and adolescent development (pp. 5-25). New York: Cambridge University Press.

McLoyd, V. C. (1998). Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist, 53(2), 185-204.

Olsson, C. A., Bond, L., Burns, J. M., Vella-Brodrick, D. A., & Sawyer, S. M. (2003). Adolescent resilience: A concept analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 26(1), 1-11.

Orygen, The National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health. (2017). Under the radar: The mental health of Australian university students. Melbourne: Orygen. The National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health.

Oshio, A., Taku, K., Hirano, M., & Saeed, G. (2018). Resilience and big five personality traits: A meta-analysis. Personality & Individual Differences, 127, 54-60.

Rammstedt, B., & John, O. P. (2007). Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the big five inventory in English and German. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(1), 203-212.

Rutter, M. (2006). Implications of resilience concepts for scientific understanding. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1094, 1-12.

Sapouna, M., & Wolke, D. (2013). Resilience to bullying victimization: The role of individual, family and peer characteristics. Child Abuse and Neglect, 11, 997-1006.

Schaan, V. K., & Vögele, C. (2016). Resilience and rejection sensitivity mediate long-term outcomes of parental divorce. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 25(11), 1267-1269.

Schmitt, D. P., Realo, A., Voracek, M., & Allik, J. (2008). Why can't a man be more like a woman? Sex differences in big five personality traits across 55 cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(1), 168-182.

Smart, D., Sanson, A., & Toumbourou, J. (2008). How do parents and teenagers get along together?: Views of young people and their parents. Family Matters, 78, 18-27.

Smith, P., Morita, Y., Junger-Tas, J., Olweus, D., Catalano, R. F., & Slee, P. T. (1999). The nature of school bullying: A cross-national perspective. London: Taylor & Frances/Routledge.

Statistics Canada. (2000). National longitudinal survey of children and youth (nlscy) cycle 3 survey instruments: Parent questionnaire. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada.

Steinberg, L. (2001). We know some things: Parent-adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 11(1), 1-19.

Tiet, Q. Q., Huizinga, D., & Byrnes, H. F. (2010). Predictors of resilience among inner city youths. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 3, 360-378.

Vassallo, S., Edwards, B., Renda, J., & Olsson, C. A. (2014). Bullying in early adolescence and antisocial behavior and depression six years later: What are the protective factors? Journal of School Violence, 13, 100-124.

VicHealth. (2015a). Community survey of young victorians' resilience and mental wellbeing. Full report: Part A and Part B. Melbourne: VicHealth.

VicHealth. (2015b). Epidemiological evidence relating to resilience and young people: A literature review. Melbourne: VicHealth.

Walper, S., & Beckh, K. (2006). Adolescents' development in high-conflict and separated families: Evidence from a German longitudinal study. In A. Clarke-Stewart, & J. Dunn (Eds.), Families count: Effects on child and adolescent development (pp. 238-270). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Warren, D. (2017). Low-income and poverty dynamics implications for child outcomes (Social Policy Research Paper No. 47). Canberra: Department of Social Services.

Wright, M. O. D., & Masten, A. S. (2005). Resilience processes in development. In S. Goldstein, & R. B. Brooks (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children (17-37). Boston, MA: Springer US.

Yu, M., & Baxter, J. (2018). Relationships between parents and young teens. In Australian Institute of Family Studies (Eds.), Growing up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children, Annual Statistical Report 2017. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

1 Standard deviation (SD) = 7.1

2 Standard deviation: Boys = 7.0; Girls = 7.1

3 Many theories have been put forward to explain the negative impact of low socio-economic status on child and adolescent health and wellbeing outcomes, including resilience (Warren, 2017). Particularly relevant here are the Investment Model and the Family Stress Model. According to the Investment Model (Becker & Tomes, 1986) low income has a direct effect on child outcomes by limiting investments by parents in material resources beneficial for their children's outcomes (e.g. education, health services, extra curricular activities) as well as their own time spent doing activities that benefit the child. According to the Family Stress Model poverty causes stress, which diminishes parents' ability to parent their child, leading to restricted social and emotional development (e.g. McLoyd, 1998). Severe or sustained stress may also affect parents' own resilience, leading to poor role modelling to their children of how to cope successfully with stressful situations.

Acknowledgements

Featured image: © GettyImages/SDI Productions