7. Gambling activity among teenagers and their parents

7. Gambling activity among teenagers and their parents

Key messages

Gambling participation is common in Australia. Estimates suggest that two in five Australian adults (6.8 million people) gambled in a typical month in 2015, with total annual gambling expenditure among regular gamblers estimated to be around $8.6 billion (Armstrong & Carroll, 2017). The most common forms of gambling in Australia include lottery, instant scratch tickets (scratchies), Electronic Gambling Machines (EGMs i.e. 'pokies' or 'poker machines'), race betting and sports betting (Armstrong & Carroll, 2017).

For some people, gambling participation can be associated with harm, including financial, relationship, social, health and emotional/psychological harm (Browne et al., 2017). In 2015, it was estimated that 8% of Australian adults (approximately 1.39 million people) had experienced one or more gambling-related problems (according to an instrument known as the Problem Gambling Severity Index), and that 1% or 193,000 adults could be classified in the high-risk category of 'problem gambling' (Armstrong & Carroll, 2017).

Although it is illegal for Australians under the age of 18 to gamble, research indicates that around half of all young people in Australia have participated in some type of gambling by age 15, increasing to around three quarters of young people by age 19 (Delfabbro, King, Lambos, & Puglies, 2009; Purdie et al., 2011). Compared to adults, adolescents may be even more vulnerable to the harmful effects of gambling, as their ability to assess risks is still developing (Miller, 2017). Regular involvement in gambling during adolescence can lead to a variety of issues including relationship problems, delinquency and criminal behaviour, depression, poor school outcomes and future unemployment (Derevensky & Gupta, 2004; Messerlian, Derevensky, & Gupta, 2005). Young people are often influenced by the gambling attitudes, beliefs and behaviours of family members, with adolescents in families that participate in gambling more likely to gamble themselves (Delfabbro & Thrupp, 2003).

Given the potential short-term and long-term consequences for adolescents, family members, and society at large, it is important to better understand the level and nature of gambling behaviours and experience of related harm at a family level. This chapter uses LSAC data to describe levels of gambling involvement and gambling-related problems among 16-17 year olds and their parents, as well as the role of selected gambling-related factors (e.g. risky behaviours, gambling-like 'electronic games', peers' characteristics). These insights may help inform a range of policy and practice initiatives to prevent or address gambling-related harm for families and young people.

7.1 Gambling activities among teenagers

Box 7.1: Gambling activities

In Wave 7 of LSAC (2016), 16-17 year olds and their parents were asked whether they had spent money on the following activities in the past 12 months:

- instant scratch tickets ('Scratchies')

- bingo

- Lotto or lottery games (e.g. Powerball, Oz lotto)

- Keno

- private betting with friends or family (e.g. cards, mahjong, pool, sports)

- poker

- casino table games (e.g. blackjack (21), roulette)

- poker machines ('pokies') or slots

- betting on horse or dog races (but not sweeps)

- betting on sports (e.g. football, cricket, e-Sports, gaming tournaments).

Items on gambling participation were designed in LSAC in collaboration with the Australian Gambling Research Centre (AGRC).

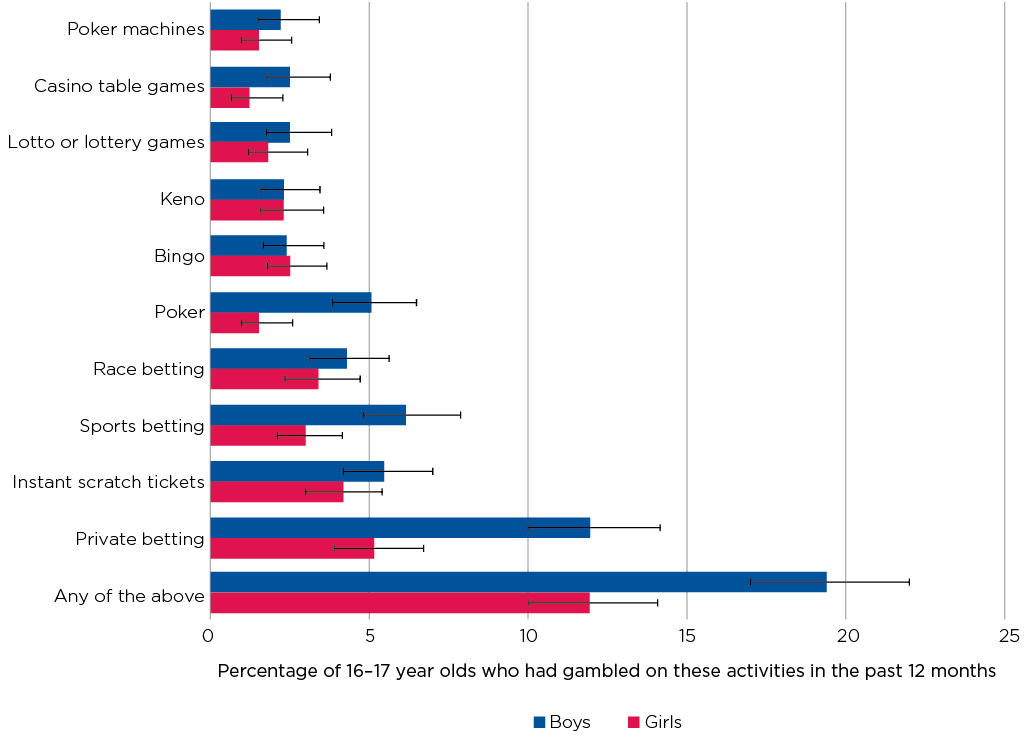

The LSAC data (n = 2,936) show that around one in five boys and one in eight girls (aged 16-17 years) reported having spent money on at least one gambling activity in the past 12 months (Figure 7.2).

The most common gambling activity that 16-17 year olds reported engaging in was private betting with friends or family; around one in eight boys and one in 20 girls reported engaging in this in the past 12 months. Private betting included activities with no legal age restrictions, such as cards or mahjong.

Despite the legal age restrictions around race and sports betting in Australia, approximately 5% of 16-17 year olds reported gambling on these activities in the past 12 months:

- Six per cent of boys and 3% of girls had bet on sports.

- One in 25 (4% of boys and 3% of girls) had bet on horse or dog races.

Both sports and race betting can be done online, and teenagers may be able to get around age restrictions when placing bets online.

In a recent Australian study of the sports‐betting motivations, attitudes and behaviours of young men aged 18-35, Jenkinson, de Lacy-Vawdon and Carroll (2018) found that 23% of bettors reported being under 18 when they first placed a bet on sports; and that sports betting had become normalised among this population of young men, facilitated by the growing accessibility of gambling and new technologies.

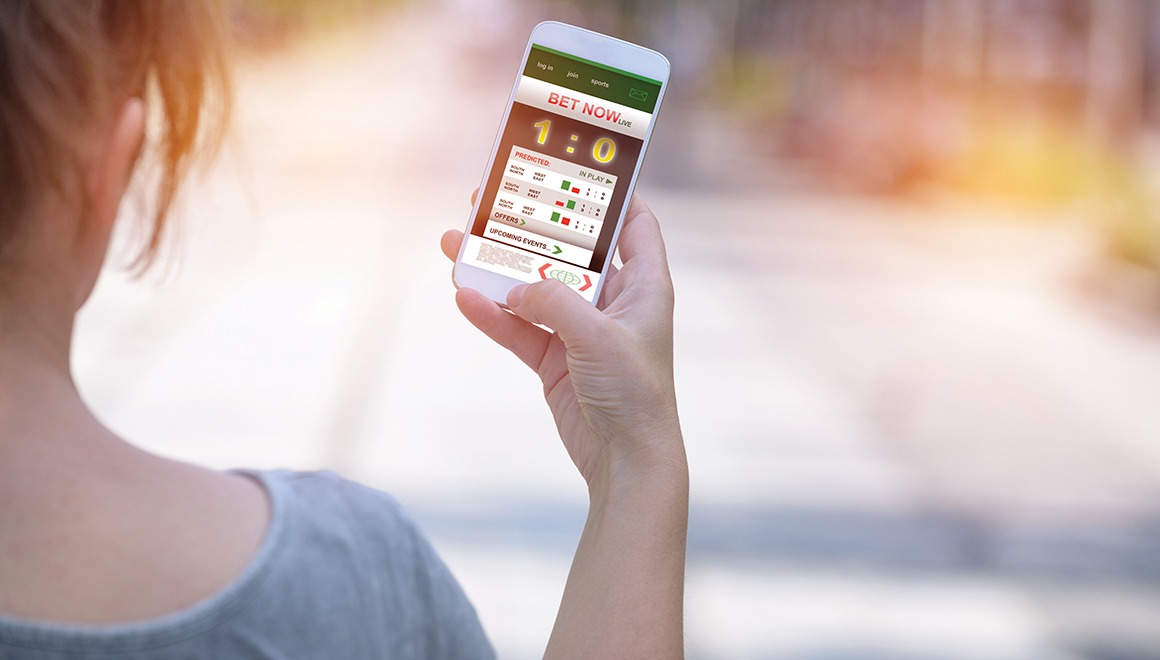

Figure 7.1: One in six 16-17 year olds reported having gambled in the past year

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Figure 7.2: Gambling activities of 16-17 year olds in 2016

Notes: 95% confidence intervals are shown by the 'I' bars in each row. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the differences in values are statistically significant. n = 1,491 boys and 1,445 girls.

Source: LSAC Wave 7 (2016), K cohort, weighted

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Instant scratchies and lottery games were reportedly less common gambling activities for 16-17 year olds:

- Around one in 20 (5%) had spent money on instant scratchies.

- Three per cent had spent money on lottery (e.g. Oz Lotto or Powerball).

This is likely due to age restrictions on the sale of these items. For example, under the Tattersalls retail code of practice in Victoria and Tasmania, 'retailers should not knowingly sell Lottery products or pay prizes to minors' (Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation, 2018).

Very few 16-17 year olds reported having spent money on gambling activities such as casino table games, EGMs or Keno. This is likely to be a result of the legal age restrictions on entry to casinos and other public gaming venues, such as TABs, hotels and clubs. However, despite acceptable proof of age being required for entry into gaming venues, around 2% of 16-17 year olds had reported having spent money on EGMs in the past 12 months, and similar proportions had spent money on casino table games and Keno. This represents around 9,000 17 year olds across Australia who had played either Keno, poker machines or casino table games in 2016.1

In order to better understand gambling-related problems among young people and their parents, the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI) was administered to young people who reported having gambled at least once in the previous 12 months (Box 7.2).

Box 7.2: Gambling-related problems

The Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI) includes nine questions that capture problematic gambling behaviour and the extent to which a person's gambling is likely to be problematic or causing harm (Ferris & Wynne, 2001). In Wave 7, LSAC study children in the K cohort, and their resident parents, were asked to rate how often their gambling activities had caused them the following problems:

- Have you bet more than you could really afford to lose?

- Have you needed to gamble with larger amounts of money to get the same feeling of excitement?

- When you gambled, did you go back another day to try to win back the money you lost?

- Have you borrowed money or sold anything to get money to gamble?

- Have you felt that you might have a problem with gambling?

- Has gambling caused you any health problems, including stress or anxiety?

- Have people criticised your betting or told you that you had a gambling problem, regardless of whether or not you thought it was true?

- Has your gambling caused any financial problems for you or your household?

- Have you felt guilty about the way you gamble or what happens when you gamble?

Responses were on a four-point scale where 0 meant 'never', 1 'sometimes', 2 'most of the time' and 3 'almost always'. These were summed to create the PGSI score, which ranged from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating a greater risk that gambling is a problem. The scores were then divided into four categories:

- Score of 0: Non-problem gamblers

- Score of 1-2: Low level of problems with few or no negative consequences.

- Score of 3-7: Moderate level of problems leading to some negative consequences.

- Score of 8 or more: Problem gambling with negative consequences and a possible loss of control

According to the PGSI score, of the 16% of 16-17 year olds (n = 462) who reported having gambled at least once in the previous 12 months, 17% of boys and 4% of girls would be classified as being at risk of, or already experiencing, gambling-related problems (i.e. a score of 1+ on the PGSI). Around 10% of boys who reported gambling would be classified as already experiencing moderate or high-level gambling problems (PGSI scores of 3 or higher, see Table 7.1). Numbers for girls are too small to be reliable; that is, seven girls scored 1+ on the PGSI.

Notes: Sample restricted to young people who reported gambling in the past 12 months. #Estimate not reliable (cell count < 10).

Source: LSAC Wave 7 (2016), K cohort, weighted

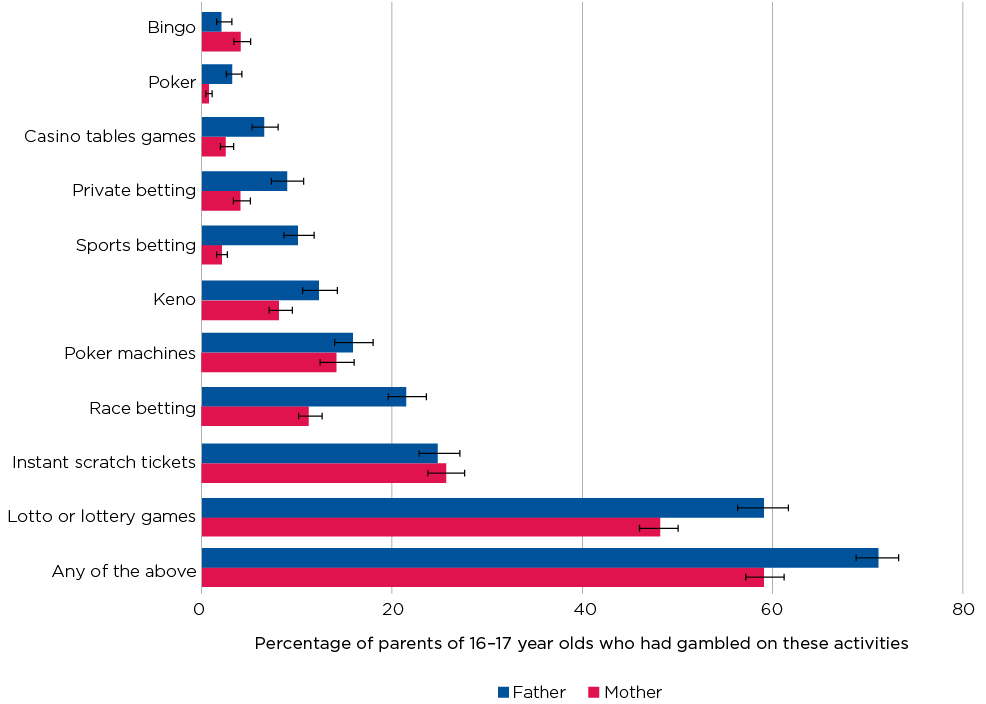

7.2 Gambling activities among parents

The LSAC data show that among parents of 16-17 year olds in 2016, six out of 10 mothers and seven out of 10 fathers reported having spent money on some type of gambling activity in the previous 12 months (Figure 7.3).2 For most parents, this gambling activity was more likely to be the purchase of a lottery ticket or instant scratch ticket, rather than a gambling activity such as EGMs or casino table games, which may be associated with greater levels of harm (e.g. Armstrong & Carroll, 2017).

The gender differences in the patterns of participation in the gambling activities of parents were similar to those of the 16-17 year olds. Males were more likely than females to spend money across the entire range of gambling activities, except bingo and instant scratch tickets. This pattern of participation for different gambling activities has been found in previous studies, with males more likely than females to engage in gambling activities such as card games (Hing, Russell, Tolchard, & Nower, 2016; Holdsworth, Hing, & Breen, 2012).

Figure 7.3: Gambling activities of parents of 16-17 year olds

Notes: Sample restricted to resident parents, n = 2,877 mothers and 1,857 fathers. 95% confidence intervals are shown by the 'I' bars at the top of each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the differences in values are statistically significant.

Source: LSAC Wave 7 (2016), K cohort, weighted

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

| Among mothers of 16-17 year olds: | Among fathers of 16-17 year olds: |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Parents who reported having spent money on one or more gambling activities in the past 12 months were also administered the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI). Among resident mothers who gambled, around 8% may were classified as being at risk of, or already experiencing, gambling-related problems, compared to 12% of resident fathers who reported having gambled in the past 12 months (Table 7.2).3 Using the 2015 Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey data, Armstrong and Carroll (2017) estimated that around 17% of Australian adults who reported having gambled regularly in the past 12 months (in a typical month) had experienced one or more gambling-related problems (PGSI scores of 1 or more).

Notes: Sample restricted to resident parents who reported gambling in the last 12 months. #Estimate not reliable (cell count < 10).

Source: LSAC Wave 7 (2016), K cohort, weighted

7.3 Behaviours associated with teenagers' gambling

Research suggests that a range of factors may influence gambling attitudes and behaviours among adolescents, including individual differences, the family environment and friends' behaviours. For example, adolescents' mental health problems, poor academic performance, and personal and peers' drinking and drug use have been found to be associated with gambling involvement (Dickson, Derevensky, & Gupta, 2008; Dowling & Brown, 2010).

Family environment

Family characteristics such as socio-economic position, parents' employment status, whether the study child speaks a language other than English at home, family structure (whether they lived with two biological parents, lived in a single-parent household or had a step-parent), and whether they lived in a major city or a regional or remote area were also considered in this research. The LSAC data suggest that these family characteristics were not significantly associated with whether or not 16-17 year olds reported having gambled in the previous 12 months.4

Some differences were observed in young people's gambling behaviour according to their parents' gambling behaviour. Among 16-17 year olds in households where no resident parent reported having gambled in the previous 12 months, 11% reported having spent money on some type of gambling activity during that time, compared to 17% of 16-17 year olds in households where one or both resident parents had gambled.5 These differences were not statistically significant. However, it should be noted that the lack of statistical significance for these characteristics may be partly due to the small numbers of LSAC study children who reported having engaged in gambling activities, particularly for girls.

Smoking, drinking and gambling

Previous studies have reported a link between adolescent gambling and other types of risky behaviour, such as consuming drugs and drinking alcohol (e.g. Dowling et al., 2017). For some young people, engagement in these behaviours may reflect a broader underlying tendency towards risk-taking (Kryszajtys et al., 2018; Shead, Derevensky, & Gupta, 2010).

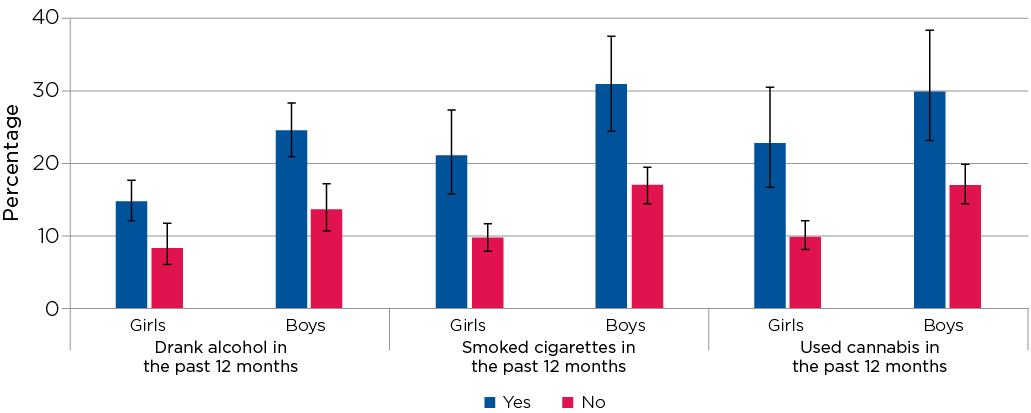

The LSAC data show that 16-17 year olds who reported drinking alcohol, smoking cigarettes or using cannabis in the past 12 months were more likely to also report having spent money on one or more forms of gambling in the past 12 months (Figure 7.4):

- Almost one in four boys, and around one in seven girls, who reported drinking alcohol in the past 12 months had also gambled during that time, compared to around one in eight boys and one in 12 girls who had not drunk alcohol.

- Three in 10 boys, and one in five girls, who reported smoking or using cannabis in the past 12 months had also gambled during that time, compared to around one in six boys and one in 10 girls who reported not smoking or using cannabis.

Figure 7.4: Percentage of 16-17 year olds who had gambled, by other types of risky behaviour

Notes: 95% confidence intervals are shown by the 'I' bars at the top of each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the differences in values are statistically significant. n = 1,487 boys and 1,444 girls.

Source: LSAC Wave 7 (2016), K cohort, weighted

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Role of peers

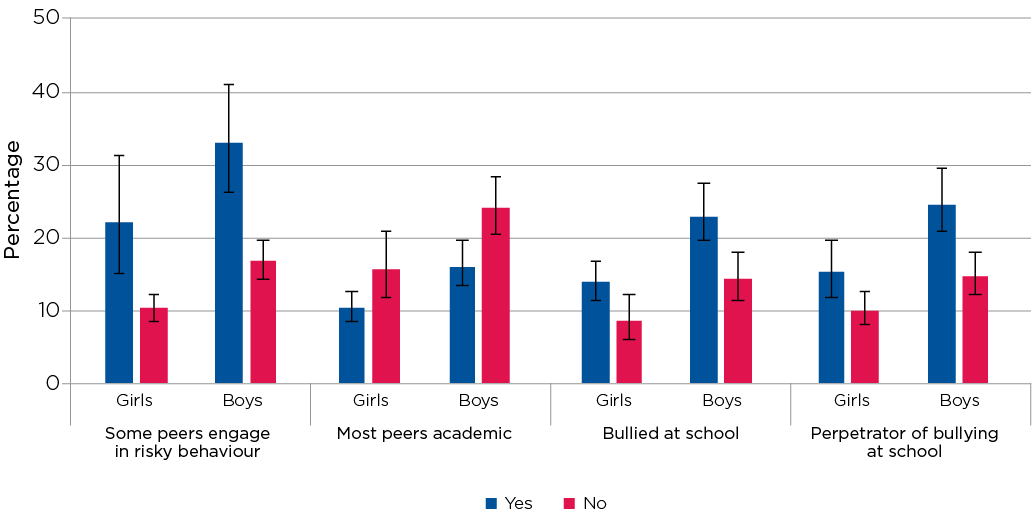

As teenagers get older, their friends may have a greater influence on their decisions about risky behaviour such as gambling. Research has shown that for young adults, friends can have a greater influence than family on their gambling behaviour (Fortune et al., 2013) as well as on their antisocial and delinquent behaviour (Farrington, Kazemian, & Piquero, 2018). The LSAC data suggest that at age 16-17, boys and girls were more likely to report having gambled if their friends had engaged in risky behaviours such as trying drugs, smoking cigarettes, breaking the law or getting into fights (Figure 7.5). On the other hand, they were less likely to report having gambled if their friends had a positive attitude towards academic achievement and were interested in doing well at school. Boys who had either been the victim or perpetrator of bullying at school were more likely to have gambled in the past year;6 however, the association between gambling and experiences of bullying was not statistically significant for girls.

These results show that in addition to the influence of parents and family, friends can play an important role in teenagers' decisions about gambling. Research suggests that while parents act as a dominant influence for the acquisition of gambling behaviours in adolescence, friends aid in the maintenance of gambling behaviours through adulthood (Gupta & Derevensky, 1997). A recent Australian study found that low- and moderate-risk gamblers were more likely to associate with friends who also gambled - and also smoked and drank alcohol - than non-gamblers and non-problem gamblers. This suggests that for gambling, there may be a role of either normalisation of behaviour through social influence or social selection, where people associate with others who share their interests (Russell, Langham, Hing, & Rawat, 2018).

Figure 7.5: Percentage of 16-17 year olds who had gambled, by peer behaviour

Notes: Peer group characteristics were measured using items adapted from the 'What my friends are like' questionnaire. Some peers engage in risky behaviours - some, almost all, or all of the study child's peers were engaged in risky behaviours (e.g. kids you know drink alcohol). Most peers academic - most or all of the study child's peers were academically oriented (e.g. kids you know work hard at school). 95% confidence intervals are shown by the 'I' bars at the top of each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the differences in values are statistically significant. n = 1,491 boys and 1,445 girls.

Source: LSAC Wave 7 (2016), K cohort, weighted

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

7.4 Gambling-like electronic games

Simulated gambling has been shown to be a risk factor that increases the likelihood of teenagers gambling with real money, and of developing gambling problems (Griffiths, 2015; Dickins & Thomas, 2016). In recent years the availability, interest in and use of gambling-like electronic games has increased sharply (Gainsbury, Hing, Delfabbro, Dewar, & King, 2015). Gambling-like electronic games, such as Zynga Poker and Big Fish Casino, imitate the characteristics of gambling but do not provide an opportunity to stake, win or lose real-world money. For this reason, these games are not currently classified as gambling. However, these games can lead to commercial gambling due to the blurred boundaries between the two, and exposure to gambling-like games at an early age may serve to normalise gambling as a suitable and acceptable activity (Griffiths & Parke, 2010).

Box 7.3: Gambling-like electronic games

In Wave 7 of LSAC, the K cohort children and their parents were asked:

'Thinking about the last 12 months, how often have you played free games like these: for example, Zynga Poker, Slottomania, Big Fish Casino. Such games could be played on social network sites (e.g. Facebook), smartphones or tablet devices or gaming consoles (e.g. PlayStation, Xbox).'

Items on frequency of playing gambling-like games were designed in LSAC, in collaboration with the Australian Gambling Research Centre (AGRC).

In addition to gambling-like games, where no real money is won or lost, micro-transactions for chance-based items in many popular video games are becoming an increasing concern. Many popular online multiplayer games, such as Overwatch and Counter-Strike, offer a variety of virtual items (e.g. more powerful weapons) in addition to standard game features. Players can obtain these items either through game play (i.e. winning or scoring), trading them with other players, or via in-game purchases of 'loot boxes' for real or in-game currency (Cleghorn & Griffiths, 2015). The widespread availability of loot boxes in modern video games has led to questions over whether they should be regulated as a form of gambling (Griffith, 2018), especially given findings from recent research that found that the more money an adult video game player spent buying loot boxes, the more likely they were to be classified as experiencing gambling problems (Zendle, McCall, Barnett, & Cairns, 2018).

The LSAC data shows that, at age 16-17, around one in four boys (24%) and one in seven girls (15%) reported having played gambling-like games in the past 12 months. Boys played these types of games more often than girls did - with around one in 10 boys, and less than one in 20 girls, playing either monthly or weekly (Figure 7.6). Still, relatively few teenagers were frequent players - only 5% of boys and 2% of girls played weekly or more often.

While more fathers than mothers of 16-17 year olds reported spending money on gambling activities, a higher percentage of mothers, compared to fathers, reported playing gambling-like games (Figure 7.6).

Figure 7.6: How often 16-17 year olds, and their parents, played gambling-like electronic games, 2016

Note: n = 1,446 boys and 1,490 girls, 2,879 mothers and 1,861 fathers.

Source: LSAC Wave 7 (2016), K cohort, weighted

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Almost one in 10 mothers reported playing gambling-like games at least weekly, compared to one in 20 resident fathers. One possible explanation for this difference is that mothers may be more risk averse, compared to fathers. That is, mothers may enjoy playing these games, but prefer not to risk money on them; while for fathers, the aim of these activities may be more about financial gain, winning, or enjoying the risk itself, rather than enjoyment of the game (Eckel & Grossman, 2008; Nelson, 2015). It is also important to keep in mind that we might be underestimating the percentage of fathers who have played gambling-like games, as non-resident parents were not asked these questions, and a relatively high proportion of resident fathers either did not answer the LSAC questionnaire or did not answer the questions about gambling and gambling-like games.7

The percentage of girls who reported having played gambling-like games was significantly higher if they had a parent who also played these types of games. However, this was not the case for boys:

- Twenty-one per cent of girls whose mothers played gambling-like games also played these games, compared to 13% of girls whose mother did not play.

- Twenty-two per cent of girls who had a resident father who played gambling-like games also played, compared to 13% of girls whose father did not play these games.

- For boys, the percentage who played gambling-like games ranged from 20-24% and there were no significant differences depending on whether or not their mother or father played these games.

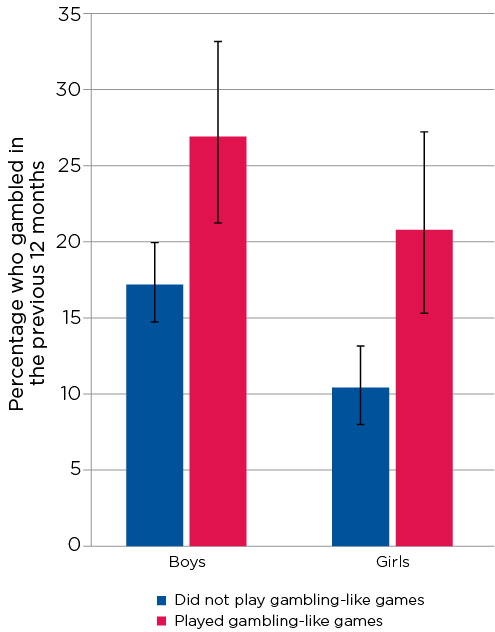

The percentage of 16-17 year olds who reported having spent money on at least one gambling activity in the past 12 months was significantly higher among those who had also played gambling-like games during that time; three out of 10 16-17-year-old boys and one in five 16-17-year-old girls who had played gambling-like games in the past 12 months had also spent money on gambling during that time (Figure 7.7). These results support the theory that, for teenagers, playing gambling-like games may increase the likelihood of transitioning to commercial gambling in the future.

Figure 7.7: Percentage of 16-17 year olds who had gambled in the past 12 months, by playing of gambling-like games

Notes: 95% confidence intervals are shown by the 'I' bars at the top of each column. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the differences in values are statistically significant. n = 1,490 boys and 1,446 girls.

Source: LSAC Wave 7, K cohort, weighted

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Summary

This chapter has provided a snapshot of gambling participation and related risk and experience of harm among Australian 16-17 year olds and their parents, and the association between parents' reported gambling activities and those of their children.

In 2016, 16% of 16-17 year olds - one in five boys and one in eight girls - reported having spent money on at least one gambling activity in the past 12 months. Just under 5% (one in 20), or around 9,000, 17 year old children in Australia reported having spent money on gambling activities that would be illegal due to age restrictions such as poker machines, poker, and casino table games.

There were some differences in gambling activities of young people by demographics. Boys were more likely to report having gambled than girls, and were more likely than girls to have gambled on private betting, sports betting and poker. Those who engaged in other risky behaviour such as smoking and drinking alcohol, or had friends who smoked or drank, were also more likely to gamble. Boys, but not girls, who had been either the victim or perpetrator of bullying at school were also more likely to report having gambled. On the other hand, teenagers who were more academically oriented and interested in doing well at school were less likely to have gambled. Universal school-based programs that target a number of risky behaviours might be effective in helping young people to develop an understanding of the potential risks and harms associated with gambling. However, more research is needed to test the effectiveness of school-based gambling education programs as evaluations of similar education programs about alcohol and tobacco have shown that, while they can raise awareness, they could have no, or even opposing, behavioural impacts (Productivity Commission, 2010).

Young people who reported playing gambling-like games in the previous 12 months were more likely to have also spent money on gambling. As with gambling activities, boys were more likely to engage in gambling-like games than girls over the last 12 months - one in four boys compared to one in seven girls had played these games. Some psychologists suggest that while gambling-like games and randomised 'loot-boxes' within online games are not currently classified as gambling, exposure to these activities at a young age may normalise gambling behaviour in the future (Griffiths, 2018). In Australia, while these activities are still legal, in a submission to the Senate Inquiry into gaming micro-transactions for chance-based items, Deblaquiere, Carroll, and Jenkinson (2018) recommended the prohibition of micro-transactions for chance-based items in online games available in Australia in order to alleviate the public health risks and associated costs with further normalising gambling in the Australian community through the provision of these items.

Parents also played an important role in young people's engagement in gambling activities and gambling-like games. For girls, but not for boys, having a parent who played gambling-like games was associated with playing these games. These results suggest that there may be benefits in engaging parents in preventive initiatives - focusing on informing parents about the role that their gambling behaviour might play in influencing young people's decisions around gambling and gambling-like games; and raising awareness of the potential harms of gambling for parents and their children.

Future policy and practice initiatives aimed at reducing the health, social and economic harms to young people and their families might consider limiting the availability and marketing of gambling activities; ensuring that tailored and targeted health promotion messages are built into online games that include gambling-like features; and stricter enforcement of acceptable proof of age for entry into gaming venues.

References

Armstrong, A., & Carroll, M. (2017). Gambling activity in Australia. Melbourne: Australian Gambling Research Centre, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Browne, M., Greer, N., Armstrong, T., Doran, C., Kinchin, I., Langham, E., & Rockloff, M. (2017). The social cost of gambling to Victoria. Melbourne: Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation. Retrieved from responsiblegambling.vic.gov.au/resources/publications/the-social-cost-of-gambling-to-victoria-121/

Cleghorn, J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). Why do gamers buy 'virtual assets'? An insight in to the psychology behind purchase behaviour. Digital Education Review, 27, 98-117.

Deblaquiere, J., Carroll, M., & Jenkinson, R. (2018). Submission to senate environment and communications references committee. Inquiry into gaming micro-transactions for chance-based items. Melbourne: Australian Gambling Research Centre, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Delfabbro, P., King, D., Lambos, C., & Puglies, S. (2009). Is video-game playing a risk factor for pathological gambling in Australian adolescents? Journal of Gambling Studies, 25(3), 391-405.

Delfabbro, P., & Thrupp, L. (2003). The social determinants of youth gambling in South Australian adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 26(3), 313-330.

Derevensky, J. L., & Gupta, R. (Eds.). (2004). Gambling problems in youth: Theoretical and applied perspectives. Springer Science & Business Media.

Dickins, M., & Thomas, A. (2016). Is it gambling or a game? Simulated gambling games: Their use and regulation (AGRC Discussion Paper No. 5). Melbourne: Australian Gambling Research Centre, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Dickson, L. M., Derevensky, J. L., & Gupta, R. (2008). Youth gambling problems: Examining risk and protective factors. International Gambling Studies, 8(1), 25-47.

Dowling, N. A., & Brown, M. (2010). Commonalities in the psychological factors associated with problem gambling and Internet dependence. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 13(4), 437-441.

Dowling, N. A., Merkouris, S. S., Greenwood, C. J., Oldenhof, E., Toumbourou, J. W., & Youssef, G. J. (2017). Early risk and protective factors for problem gambling: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 51, 109-124.

Eckel, C. C., & Grossman, P. J. (2008). Men, women and risk aversion: Experimental evidence. Handbook of Experimental Economics Results (pp. 1061-1073). Elsevier.

Farrington, D. P., Kazemian, L., & Piquero, A. R. (Eds.). (2018). The Oxford handbook of developmental and life-course criminology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ferris, J., & Wynne, H. (2001). The Canadian problem gambling index: Final report. Canada: The Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. Retrieved from www.ccgr.ca/en/projects/resources/CPGI-Final-Report-English.pdf

Fortune, E. E., MacKillop, J., Miller, J. D., Campbell, W. K., Clifton, A. D., & Goodie, A. S. (2013). Social density of gambling and its association with gambling problems: An initial investigation. Journal of Gambling Studies, 29(2), 329-342.

Gainsbury, S. M., Hing, N., Delfabbro, P., Dewar, G., & King, D. L. (2015). An exploratory study of interrelationships between social casino gaming, gambling, and problem gambling. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 13(1), 136-153.

Griffiths, M. D. (2015). Adolescent gambling and gambling-type games on social networking sites: Issues, concerns, and recommendations. Aloma: revista de psicologia, ciències de l'educació i de l'esport Blanquerna, 33(2), 31-37.

Griffiths, M. D. (2018). Is the buying of loot boxes in video games a form of gambling or gaming? Gaming Law Review, 22(1), 52-54.

Griffiths, M. D., & Parke, J. (2010). Adolescent gambling on the Internet: A review. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 22(1), 59-75.

Gupta, R., & Derevensky, J. (1997). Familial and social influences on juvenile gambling behavior. Journal of Gambling Studies, 13(3), 179-192.

Hing, N., Russell, A., Tolchard, B., & Nower, L. (2016). Risk factors for gambling problems: An analysis by gender. Journal of Gambling Studies, 32(2), 511-534.

Holdsworth, L., Hing, N., & Breen, H. (2012). Exploring women's problem gambling: A review of the literature. International Gambling Studies, 12(2), 199-213.

Jenkinson, R., de Lacey-Vawdon, C., & Carroll, M. (2018). Weighing up the odds: Young men, sports and betting. Melbourne: Australian Gambling Research Centre, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Kryszajtys, D. T., Hahmann, T. E., Schuler, A., Hamilton-Wright, S., Ziegler, C. P., & Matheson, F. I. (2018). Problem gambling and delinquent behaviours among adolescents: a scoping review. Journal of Gambling Studies, 34(3), 893-914.

McComb, J. L., & Sabiston, C. M. (2010). Family influences on adolescent gambling behavior: a review of the literature. Journal of Gambling Studies, 26(4), 503-520.

Messerlian, C., Derevensky, J., & Gupta, R. (2005). Youth gambling problems: A public health perspective. Health Promotion International, 20(1), 69-79.

Miller, H. (2017). Gen Bet: has gambling gatecrashed out teens? Melbourne: Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation.

Nelson, J. A. (2015). Are women really more risk‐averse than men? A re‐analysis of the literature using expanded methods. Journal of Economic Surveys, 29(3), 566-585.

Productivity Commission. (2010). Gambling Inquiry Report (Report no. 50). Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Purdie, N., Matters, G., Hillman, K., Murphy, M., Ozolins, C., & Millwood, P. (2011). Gambling and young people in Australia. Melbourne: Gambling Research Australia.

Russell, A., Langham, E., Hing, N., & Rawat, V. (2018). Social influences on gamblers by risk group: An egocentric social network analysis. Melbourne: Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation.

Shead, N. W., Derevensky, J. L., & Gupta, R. (2010). Risk and protective factors associated with youth problem gambling. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine And Health, 22(1), 39.

Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation. (2018). Tatts Responsible Gambling Code of Conduct. Melbourne: Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation. Retrieved from www.vcglr.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/archive_codes_of_conduct_tatter...

Zendle, D., McCall, C., Barnett, H., & Cairns, P. (2018). Paying for loot boxes is linked to problem gambling, regardless of specific features like cash-out and pay-to-win: A preregistered investigation. doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/6e74k

1 At Wave 7 of LSAC, study children were aged 16 or 17. Study children in the K cohort were born between March 1999 and May 2000, and the majority (54%) were aged 16 at the time of their Wave 7 interview.

2 In Wave 7 of LSAC, parents who lived in the study child's main household were asked about whether they had engaged in any gambling activities in the past 12 months. While the majority of mothers (96%) responded to the questions about gambling, 29% of resident fathers either did not answer the questions about their gambling participation, or did not complete the questionnaire at all. Therefore, when interpreting the figures for fathers' gambling, it is important to keep in mind that the estimates of their gambling activities may not be representative of the national population.

For the purpose of this chapter, 'parents' include biological, step, foster and adoptive parents. Of the 3,034 study children in the K cohort in Wave 7, 2.8% had no resident mother in their primary household, 93.7% had a resident mother who responded to the gambling questions and 3.5% had a resident mother who either did not answer the question about their gambling participation or did not complete the questionnaire at all; 21.2% had no resident father in their primary household, 56.2% had a resident father who responded to the gambling questions and 22.7% had a resident father who either did not answer the question about their gambling participation or did not complete the questionnaire at all. Parents who did not live in the study child's primary household were not asked about their gambling activities.

3 It is important to keep in mind that for fathers, this figure may be an underestimate due to the relatively high percentage of resident fathers who did not provide information about their gambling activities.

4 These results differ from previous research (McComb & Sabiston, 2010).

5 Includes two-parent households in which at least one parent had gambled; and single-parent households in which the parent had gambled.

6 At 16-17 years, 80% of adolescents who said they had bullied others in the past 12 months also reported having been bullied during that time.

7 This issue remains even after survey weights are applied as the weights are household specific rather than parent specific.

Acknowledgements

Featured images: © GettyImages/humonia