8. Shop or save: How teens manage their money

8. Shop or save: How teens manage their money

Key messages

Managing money day to day - keeping track of expenses and avoiding getting into debt - is an important life skill. Money management, along with financial information seeking and the ability to plan and save for important purchases and unexpected expenses, makes people financially capable (Australian Securities & Investments Commission (ASIC), 2018).1 For many people, economic socialisation, the process of acquiring and building financial skills, knowledge and attitudes, including emotional attitudes, starts in childhood and continues to develop in adolescence (Rinaldi & Bonanomi, 2011). Money habits are difficult to change later in life (Hornyák, 2015) and can therefore influence financial behaviour in adulthood (Nagy & Tóth, 2012).

In many ways the economic world of adolescents is different from that of adults, most of whom are financially independent:

- Most adolescents are not responsible for their living costs. However, some adolescents begin to work and to live more independently, taking on greater responsibility for regular bills (e.g. food) and larger financial commitments (e.g. buying a car).

- Some parents offer their children opportunities to develop financial capability. For example, they might provide pocket money and expect their adolescent child to cover certain necessities, e.g. mobile phone bills (Otto, 2009).

- Adolescents' reasons to save might be different from those of adults. For example, saving money 'for a rainy day' might not be as important for adolescents living with parents who take responsibility for unexpected expenses (Luksander, Németh, & Zsótér, 2017), but 'precautionary savings' are important for many adults.

- Adolescents' financial freedom is somewhat limited - they are likely to be given some guidelines or rules on what they may spend their money on - and they are not 'contractually capable'. That is, they cannot legally buy certain things, such as cigarettes or alcohol, and cannot enter into a mobile phone contract without a parent's permission.

- Young people are growing up in a society where money is becoming invisible, making it harder for them to fully understand what things cost.

This chapter examines money management styles at age 16-17.2 The analysis considers three groups of adolescents based on their approach to money management: 'savers' (adolescents with an inclination to saving), 'spenders' (adolescents with a tendency to spending), and adolescents with a more neutral money management style. The chapter contributes to the understanding of the determinants of money management styles in adolescence.3 In particular, the chapter describes how 16-17 year olds use and manage their money, and the degree of parental financial support provided. It then examines associations between money management styles and the opportunities that children might have had to practise money management throughout childhood. For example, are there differences in the money management styles of young people who received pocket money and had savings accounts when they were growing up?

8.1 How do teens use and manage their money?

At age 16-17, most study teenagers were still in secondary school and almost all were still living in their parents' home.4 While some 16-17 year olds have part-time jobs, the majority are likely to rely on their parents for everyday living expenses. At ages 16-17, some teens may save for major purchases such as a car or overseas travel, while others might prefer to spend on present-focused things such as clothes, phones, technology, games, or sports and social activities.

Box 8.1 Money management styles

In Wave 7 of LSAC, study children in the K cohort (aged 16-17) were asked: 'When dealing with your money on a day-to-day basis, how much does this statement sound like you?

- I like to look ahead and plan for the future financially.

- I am cautious with my money and try to avoid getting into debt as much as possible.

- I am present-focused and financially like to live for today.

- I find it very easy to spend my money.

- I like to save money and I would say that the phrase 'save for a rainy day' applies to me.

- 'Spend, spend, spend' is a phrase that applies to me.'

These questions were adapted from the Financial Services Authority (FSA), 18-24 Ethnographic sessions recruitment questionnaire from 2004.

Study participants could choose from the following options: 1 'Not at all', 2 'A little', 3 'Somewhat', 4 'Quite a lot' or 5 'Very much'.

Responses to these questions were summed (with scores for the statements 3, 4 and 6 reversed) to create a standardised measure of money management behaviours (Cronbach's alpha 0.78). This scale, consisting of summed responses, was then divided into three groups of equal size (tertiles), representing 'spenders', 'savers' and those with a more neutral money management style.

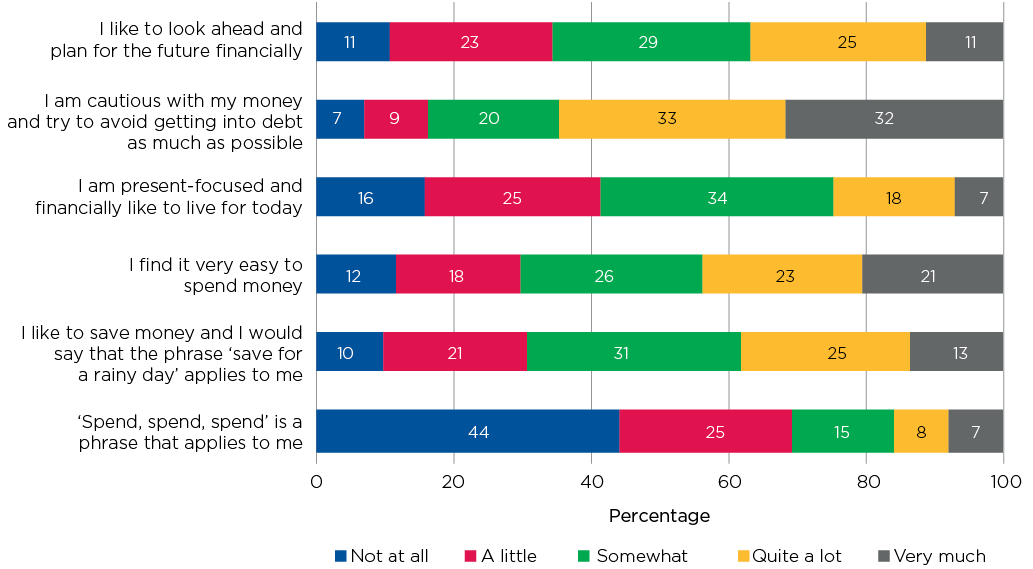

The LSAC data show that, while some 16-17 year olds were more cautious with their money than others, most had a reasonably cautious style towards money management. For example, around one in seven 16-17 year olds responded either 'quite a lot' or 'very much' to the statement, '"Spend, spend, spend" is a phrase that applies to me', while almost half (44%) responded 'not at all' ( Figure 8.1 ). More boys than girls disagreed with this statement, with two out of five girls and three out of five boys saying that it did not apply to them.

Over 40% said that they found it very easy to spend their money (either quite a lot or very much). A higher percentage of girls than boys said that they found it very easy to spend their money - 18% of boys and 23% of girls responded 'very much' to this statement (results not shown).

While there were differences in boys' and girls' responses to the statements about spending habits, with girls having a slightly higher preference for spending, there were no significant differences in boys' and girls' responses to the statements about planning for the future financially, saving money and avoiding debt.

Responses to the statements, 'I like to look ahead and plan for the future financially' and 'I like to save money and would say that "save for a rainy day" applies to me' were relatively evenly spread across the scale, with just over one third of 16-17 year olds responding either 'quite a lot' or 'very much', around three out of 10 responding 'somewhat' and the remaining third saying 'a little' or 'not at all'. Similarly, while one in four 16-17 year olds responded either 'quite a lot' or 'very much' to the statement, 'I am present focused and financially like to live for today', around two in five responded 'not at all' or 'a little', and around one third responded 'somewhat'.

At this age, money management style is more about preferences rather than responsibility. While some teenagers have a preference for planning for the future, it is also not uncommon for 16-17 year olds with relatively few financial responsibilities and limited income, either from part-time work or pocket money, to be focused on the near future when it comes to money.

Figure 8.1: Money management behaviour, 16–17 year olds

Note: n = 2,947.

Source: LSAC Wave 7, K cohort, weighted

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

In the matter of being cautious with money and avoiding getting into debt, almost two thirds of 16-17 year olds responded 'quite a lot' or 'very much'. While this suggests that most 16-17 year olds are cautious when it comes to money, this result is likely to be at least partly because, for 16-17 year olds, opportunities for getting into debt are limited. In Australia, people under the age of 18 cannot legally apply for credit cards in their own name, but parents are able to add their children as supplementary cardholders to their credit card account - and remain legally responsible for all expenses. For young people in this age group, debt may be a result of borrowing money from friends or family members.

Responses to the six statements about money management, described above, were summed to create a scale that was subsequently divided into three groups of equal size (tertiles), representing adolescents (Box 8.1, above):

- who have an inclination to save - 'savers' (top 33%)

- those with a preference for spending - 'spenders' (bottom 33%)

- those with a more neutral money management style, with no strong preference for being either present-focused or future-focused when it comes to money - 'neutral' (middle 33%).

It is important to keep in mind when considering these three groups that these are money management 'styles' - being in the 'spender' category does not necessarily mean that they do not save any money at all; and while 'savers' were more cautious with their money and had a higher preference for saving than the 'spender' group, most said that they found it 'a little' easy to spend their money. Below, money management styles of 16-17 year olds are examined by financial support from parents and opportunities to practise money management, i.e. receipt of pocket money, spending habits and use of financial services.

8.2 Financial support from parents

Money management styles might be linked to the financial support that parents give to their children. LSAC has collected information about the types of financial support that parents give to the study child, above and beyond household expenses (Box 8.2). Adolescents who receive financial support from their parents may value the role that their parents play in their monetary matters and be inclined to budgeting (Kidwell, Brinberg, & Turrisi, 2003). Alternatively, they might not feel responsible for managing their budget and could be inclined to spending more than saving (Kidwell et al., 2003).

Box 8.2: Financial support from parents

In Wave 7 of LSAC, adolescents in the K cohort were asked whether, in the last 12 months, their parents or other family members provided them with any of the following types of financial support:

- Purchasing real estate (including mortgage repayments, outright purchases and purchasing investment properties)

- Paying for accommodation (rent or board payments)

- Other household expenses (e.g. gas and electricity)

- Purchasing a car or similar (including car loans or outright purchases)

- Other motor vehicle costs (car insurance, motor vehicle running costs, registration, petrol)

- Education fees (e.g. university or TAFE fees or other study-related costs)

- Extracurricular activity costs (e.g. sports and sports gear, singing or music lessons, and musical instruments etc.)

- Personal bills or expenses (phone, credit card bills etc.)

- Paying fines

- Medical costs (including individual health insurance, dental expenses etc.)

- A general living allowance (e.g. pocket money)

- Ad hoc money as needed

- Allowing them to live in their or another family member's investment property rent free or for low rent

- Other expenses.

Adolescents who lived at home at the time of the survey or at any time in the last 12 months were asked to exclude household expenses that were meant for all people in that household (e.g. rent or mortgage payments, electricity/gas, family health insurance etc.)

Information on financial support from parents was obtained from the Youth in Focus, Wave 2 Continuing Youth Respondents Questionnaire (Australian National University, 2018).

Most 16-17 year olds were still at school, and while almost half had part-time jobs, parents were still responsible for the majority of their children's day-to-day expenses. The amount of financial support that parents provided for their teenage children was substantial, ranging from helping with the purchase of a car to education and medical costs, as well as extracurricular activities, personal bills and general living expenses (Table 8.1). Around half of 16-17 year olds received a general living allowance (pocket money). On average, those who received regular pocket money were given around $40 per week.

Money management style by parental financial support

The types and amounts of financial support that parents provided for their children at 16-17 years varied considerably, and there were relatively few significant associations between parental financial support and adolescents' money management styles. The only type of parental financial support that was associated with money management style in adolescents was support for medical expenses - the percentage of spenders was significantly higher among those who said they did receive parental support for medical costs (38% compared to 30% for those who did not receive this support).

Notes: n = 2,907. Sample excludes 32 study participants who were no longer living with their parents.

Source: LSAC Wave 7, K cohort, weighted

8.3 Opportunities to practise money management at an early age

Parents are thought to play a key role in teaching children about money and money management (Gudmunson & Danes, 2011; Kim, LaTaillade, & Kim, 2011). Parents can provide opportunities for money management by providing pocket money or an allowance, by guiding them on how to spend the money and by opening a savings account for them from a young age (Lewis & Scott, 2000). These practices can be a starting point for conversations about money, a discussion that 84% of students in Australia have with their parents at least once a month (Thomson & De Bortoli, 2017). The opportunities to familiarise children with the concepts of owning money, spending money and saving money start them on the way to developing money management skills that can be carried through to adulthood.

Pocket money

Giving children and adolescents pocket money can improve their knowledge about money (Edwards, 2014), providing them with an opportunity to manage their own money and allowing them to practice delayed gratification - deciding whether to spend their money now or save it for something bigger in the future.

Data from the International Student Assessment (PISA) showed that around 76% 15-year-old Australian students received pocket money in 2012 (32% without having to do any chores at home and about 44% for regularly doing chores at home) (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD], 2014). In 2018, a survey by the Financial Planning Association of Australia (FPA, 2018) found that 73% of 14-18 year olds received pocket money, 46% of them got between $10 and $39 each week and one in seven got over $40 each week.

From when children were aged 10-11 years of age, LSAC has collected information about whether children receive pocket money and how much they receive (Box 8.3). The LSAC data show that fewer adolescents received pocket money at earlier ages. Almost two in five 10-11 year olds (37%) received regular pocket money; and while approximately three out of five 12-13 and 14-15 year olds received some pocket money, less than four in 10 received it on a regular basis (Table 8.2). Among those who received pocket money, average weekly amounts ranged from $8 for 10-11 year olds in 2010 to $17 for 14-15 year olds in 2014. The amount of pocket money that young people received was not associated with their parents' income (Edwards, 2014).

Box 8.3: Pocket money

In Waves 4, 5 and 6 of LSAC, when children in the K cohort were aged 10-11, 12-13 and 14-15, parents were asked: 'Does the child receive pocket money on a regular basis?' (In Waves 5 and 6 they were first asked if the child received pocket money.)

The question on receiving pocket money was drawn from measures used in the Child Employment Survey 2006, by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (ABS, 2007).

The question on receiving pocket money on a regular basis was adapted from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) that was conducted in 1997 (Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, 1997).

If the child received regular pocket money, parents were then asked: 'How much money does the child receive?'

This question was adapted from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) that was conducted in 1997 (Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, 1997).

Parents who said that their child received pocket money (regular or irregular) were asked:

Does the child have to do any of the following to get his/her pocket money?

- Chores or tasks

- Follow household rules

- Homework.

Does the child get extra pocket money for:

- Good behaviour

- Following household rules

- Doing well at school

- Completing homework?

Does the child get any of his/her pocket money stopped or taken away for:

- Poor behaviour

- Not following household rules

- Not doing well at school

- Not completing homework?

These items were designed in LSAC.

Notes: a Sample restricted to those who received regular pocket money. #Estimate not reliable (cell count <20).

Source: LSAC Waves 4-6, K cohort, weighted

Pocket money can be a way of teaching children the link between work and money. While some parents pay children for doing chores, others believe that children should do chores without being paid to contribute to the running of the household. For some, it may be a way of encouraging good behaviour - by giving extra money for good behaviour or doing well in school, or by withholding money or taking it away as a punishment for bad behaviour.

The LSAC data show that at age 10-11, more than three quarters of those who received pocket money were given this money for doing household chores. By age 14-15, pocket money was conditional on doing chores for around two thirds of those who received pocket money (Table 8.3). Making pocket money conditional on following household rules or doing homework was less common.

Overall, around eight out of 10 children at 10-11 and 12-13 years and seven out of 10 at 14-15 years who received pocket money were given money conditional on either chores, homework or following household rules.

Notes: * Indicates differences between the 'regular' and 'irregular' groups at the 5% significance level. Where 95% confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the differences in values are statistically significant. Age 12-13: pocket money conditional on following household rules: 38% for irregular, 50% for regular; conditional on homework: 26% for irregular, 34% for regular; pocket money stopped or taken away: 32% irregular, 43% regular; for poor behaviour: 11% irregular, 21% regular; for not following rules: 23% irregular, 33% regular. Age 14-15: extra pocket money for following rules: 13% irregular, 9% regular; extra for completing homework: 10% irregular, 6% regular.

Source: LSAC Waves 4-6, K cohort, weighted

Across all three age groups, almost three in 10 young people who received pocket money received extra for good behaviour, following household rules, doing well at school or completing homework. Across all age groups, a greater proportion of those who received pocket money received extra for doing well at school, compared to good behaviour and following household rules. Having pocket money stopped or taken away became less common as adolescents got older, with half of the 10-11 year olds and one in three 14-15 year olds who received pocket money having it withheld or taken away for bad behaviour, not following household rules, not doing homework or not doing well at school.

Money management style by pocket money

There were no significant associations between receiving pocket money at ages 10-15, or the amount of pocket money received, and money management style at age 16-17 (results not shown).5 There were also no significant associations between whether pocket money was given freely or conditional on doing chores or homework, or following household rules. However, money management style at age 16-17 was related to receipt of extra pocket money at ages 12-13 and 14-15; and also to having pocket money stopped or taken away.

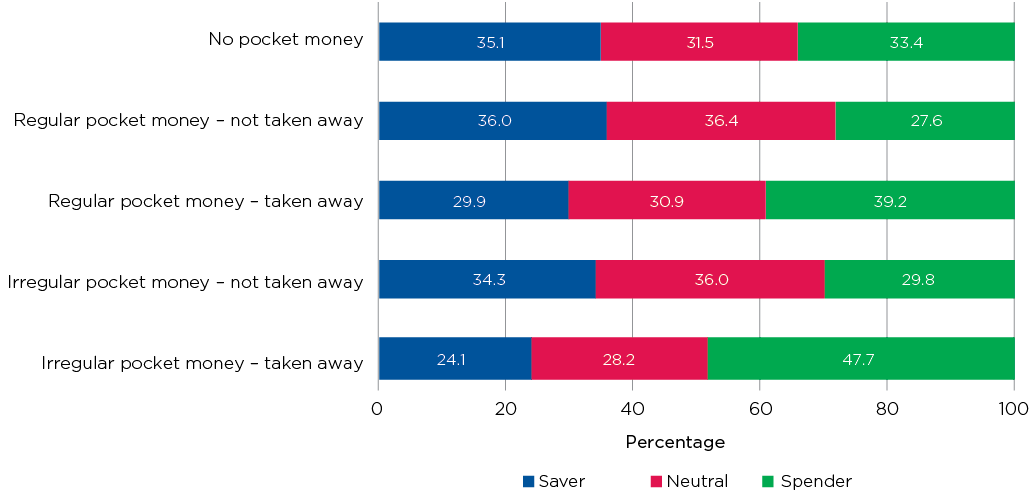

Among those who were given irregular pocket money and received extra money for good behaviour, chores or doing well at school at age 14-15, the percentage of 16-17 year olds in the 'spender' category was significantly higher than for those who did not receive extra pocket money, and those who received no pocket money at all (Figure 8.2). Almost half (46%) of those who received irregular pocket money 'with extra' were spenders, compared to around one third of other 16-17 year olds.

Among 16-17 year olds who received irregular pocket money at age 14-15, with money stopped or taken away under certain conditions, almost half (48%) had a 'spender' money management style, as did around two in five (39%) of those who received regular pocket money at age 14-15 and had it stopped or taken away (Figure 8.3). Among those who received regular or irregular pocket money at 14-15 and did not have it stopped or withheld, less than three in 10 were in the spender category.

Figure 8.2: Money management style, 16-17 year olds in 2016, by receipt of extra pocket money at age 14-15

Notes: The proportions of children who are 'savers', 'spenders' and in the 'neutral' categories are compared between groups, e.g. proportion of savers is compared between those receiving 'no pocket money' and those receiving 'regular pocket money - with extra'. The percentage of spenders in the 'Irregular pocket money - with extra' group is significantly higher (at the 5% level) than that of other groups. Where 95% confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the differences in values are statistically significant. Similar associations were found for pocket money at age 12-13 and money management at age 16-17. n = 2,947.

Source: LSAC Waves 6 and 7, K cohort, weighted

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Figure 8.3: Money management style, 16-17 year olds in 2016, by whether pocket money was withheld or taken away at age 14-15

Notes: The proportions of children who are 'savers', 'spenders' and in the 'neutral' categories are compared between groups, e.g. proportion of savers is compared between those receiving 'no pocket money' and those receiving 'regular pocket money - taken away'. The percentage of spenders in the 'irregular pocket money - taken away' and 'regular pocket money - taken away' groups are significantly higher (at the 5% level) than those in other groups. Similar associations were found for pocket money at age 12-13 and money management at age 16-17. n = 2,947.

Source: LSAC Wave 7, K cohort, weighted

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

These results suggest that while money management style at age 16-17 was not related to whether adolescents had received pocket money in early adolescence, how much they got or whether or not they received money for doing chores, it may be related to the way that parents gave pocket money to their children and, in particular, whether pocket money was used as a reward or a punishment. It is also possible that children may have tried harder to please their parents when they had something that they especially wanted to buy. When money is given as a reward, parents may also encourage adolescents to spend the money on something that they wanted, rather than save it. On the other hand, having money taken away or withheld, particularly if pocket money was not received on a regular basis, may create uncertainty about the amount of money that will be available from week to week, and this may influence adolescents' money management styles. This pattern of having money taken away or withheld could also be related to parental inconsistency over time and between the mother and father, which is associated with poor mental health in adolescents (Dwairy, 2010).

Figure 8.4: Teenagers who were saving or investing at age 12-13 were more likely to be savers at age 16-17

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

8.4 What do teenagers spend their money on?

Money management styles in adolescence might also be associated with the way children spend their money earlier on, which in turn depends on the combination of how much money they have and what they want or need to pay for independently. According to parents' reports, most teenagers spent their money mainly on personal expenses - increasing from almost 70% for 12-13 year olds to 82% of 16-17 year olds (Table 8.4). Savings and investment also increased as teenagers got older, with just over 40% of 12-13 year olds and 52% of 16-17 year olds using their money for saving or investment.

Notes: Sample excludes 32 study participants who were no longer living with their parents. n.a. = not asked at age 12-13 and 14-15. #Estimate not reliable (cell size <20).

Source: LSAC Waves 5-7, K cohort, weighted

Money management style by spending habits

In terms of money management style at age 16-17, saving habits at age 12-13 and 14-15 were related to money management at age 16-17, with significantly more of those whose parents reported that they were saving or investing earlier in adolescence having a 'saver' money management style at age 16-17 (Table 8.5). On the other hand, compared to other 16-17 year olds, a significantly higher percentage of those who had been spending their money on personal expenses since early adolescence were spenders at age 16-17. Most 16-17 year olds had their own phone. Teens aged 16-17 were more likely to be spenders if they had paid for their own mobile or internet data when they were 14-15 years old, than if they had not.

Notes: * Indicates a significant difference from the 'Yes' category at the 5% level of significance. Where 95% confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the differences in values are statistically significant. There were no significant differences in adolescents' money management styles according to other types of spending listed in Table 8.4. n = 2,879 at age 12-13, 2,821 at age 14-15 and 2,868 at age 16-17.

Source: LSAC Waves 5-7, K cohort

8.5 Use of financial services

Having a savings account from a young age can help to familiarise children with the concept of saving money, starting them on the way to developing money management skills. When children receive a bank statement, it provides an opportunity for parents to talk with their child about how much money they have saved and how much interest they have received. In the teenage years, having a bank account with an EFTPOS facility, or access to a credit card, provides young people with more opportunities for spending their money, and independence in making decisions about how to spend their money.

In LSAC, information about use of financial products was collected from age 12-13 (Box 8.4). At age 12-13, 41% of teenagers reported having a savings account in their own name and 7% had an account that allowed them to withdraw money (Table 8.6). By age 16-17, 79% of teenagers reported having a bank account with an EFTPOS facility and less than 3% had access to a credit card.

Box 8.4: Bank accounts and credit cards

In Waves 5 and 6 of LSAC, when children in the K cohort were aged 12-13 and 14-15, parents were asked: 'Does study child have any of the following?

- Use of a savings account in his/her own name

- Use of a credit card

- Use of an ATM pin number/account

- None of the above.'

In Wave 7, when study children were aged 16-17, the list of financial products was changed to:

- A bank account with a debit/ATM/EFTPOS card in their own name

- Use of a bank account with a debit/ATM/EFTPOS card in someone else's name

- A bank account without a debit/ATM/EFTPOS card

- A credit card in their own name

- Use of a credit card in someone else's name

- None of the above.

Information on bank accounts and credit cards was obtained from the Child Employment Survey 2006, and by the ABS and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (ABS, 2007).

Source: LSAC Waves 5-7, K cohort, weighted

Money management style by use of financial services

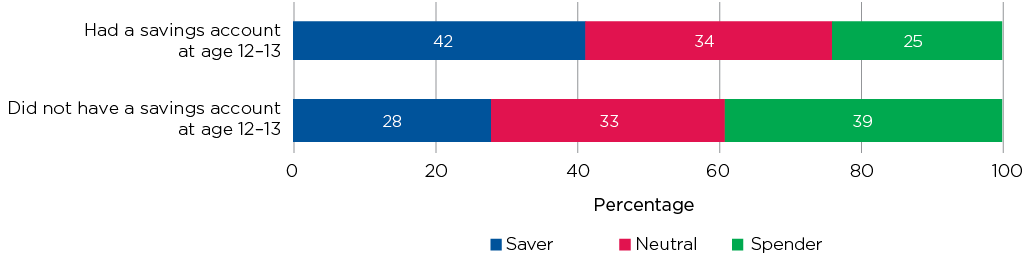

Having a savings account at age 12-13 was related to money management style at age 16-17. Among those who had a savings account at that age, just over two out of five had a 'saver' style of money management, and one in four had a 'spender' style (Figure 8.5). Of those who did not have a savings account at age 12-13, almost two in five were 'spenders' and almost three out of 10 were 'savers'.

This difference in adolescents' money management styles suggests that encouraging young people to save money early in adolescence is associated with their money management style in the teenage years. Having a savings account may also help young people resist the temptation to spend money that they have saved. It can also protect young people from 'financial exclusion' in adulthood. Financial exclusion is when 'individuals lack access to appropriate and affordable financial services and products - the key services and products are a transaction account, general insurance and a moderate amount of credit' (Connelly, 2014). In 2013, 17% of Australian adults (18+) were either fully excluded (with no financial services products) or severely excluded (with only one financial services product) from financial services. Rates of exclusion were substantially higher among those with incomes below $15,000 (Connelly, 2014).

Figure 8.5: Money management style at age 16-17, by whether they had a savings account at age 12-13

Notes: The proportions of children who are 'savers', 'spenders' and in the 'neutral' categories are compared between those who did and did not have savings accounts. Differences between the percentage of spenders and the percentage of savers, according to whether they had a savings account are statistically significant at the 5% level. Where 95% confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the differences in values are statistically significant. n= 2,663.

Source: LSAC Waves 5 and 7, K cohort, weighted

Credit: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2019 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Summary

This chapter has provided a snapshot of money management behaviours of 16-17 year olds in 2016. It looked at the relationship between money management styles at age 16-17 and concurrent financial support from parents. It also examined the associations between money management styles at age 16-17 and receiving pocket money throughout childhood and early adolescence, how money was spent and use of a savings account.

Parents are thought to play a key role in teaching children about money and money management (Gudmunson & Danes, 2011; Kim, LaTaillade, & Kim, 2011). Understanding people's money management styles in adolescence and the characteristics that determine these styles may help reduce the risks associated with the financial decisions that young people face, especially in a climate where the accumulation of relatively large amounts of debt (e.g. credit card debt and bank loans) by early adulthood is relatively common (Hoeve et al., 2014; Lusardi, Mitchell, & Curto, 2010).

Most 16-17 year olds were supported by their parents and had no financial responsibilities. The money they had at their disposal was also relatively small. Receiving pocket money at ages 10-15, the amount of pocket money received and the conditions placed on receiving pocket money (e.g. doing household chores) were not related to money management styles at age 16-17. However, receiving pocket money irregularly 'with extra' and having pocket money stopped or taken away were associated with a higher inclination to spend money. Therefore, whether pocket money is a useful tool for developing young people's money management skills is likely to depend on the regularity and freedom that parents give their children about how pocket money should be used.

While some parents might place no restrictions on what the pocket money is used for or give it to their children as 'spending money', others may encourage the idea of saving for a larger purchase in the future, donating to charity, or a combination of all three (i.e. no restrictions, saving and donating). For example, the Australian Securities & Investments Commission (ASIC) suggests that children have three jars for their pocket money - one for spending, one for saving and one for donating (ASIC, 2019). Another suggestion for teaching children about the importance of saving money is to save 50%, spend 40% and donate the remaining 10% to charity (ASIC, 2019). As teenagers get older, parents may be less likely to influence behaviours through pocket money.

Developing savings habits early in life was found to be important, with higher percentages of those who had savings accounts and who were saving or investing at age 12-13 reporting a 'saver' money management style at age 16-17.

Teaching adolescents about money is important for life. Money skills should be developed from an early age and fostered into young adulthood. The more financially knowledgeable children and adolescents are and the more opportunities they have to practice money management skills, the better spending and saving decisions they are likely to make throughout their lives.

References

Ali, P., Anderson, M. E., McRae, C. H., & Ramsay, I. (2014). The financial literacy of young Australians: An empirical study and implications for consumer protection and ASIC's National Financial Literacy Strategy. Company and Securities Law Journal, 32(5), 334-352.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2007). 6211.0 - Child Employment, Australia, Jun 2006. Canberra: ABS. Retrieved from www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/6211.0Main+Features1Jun%202006?OpenDocument

Australian National University (ANU). (2018). Youth in Focus - College of Business and Economics - ANU. Canberra: ANU. Retrieved from https://www.rse.anu.edu.au/research/centres-projects/youth-in-focus/

Australian Securities & Investments Commission (ASIC). (2018). National Financial Capability Strategy. Canberra: ASIC. Retrieved from financialcapability.gov.au/#fh5co-strategy

ASIC. (2019). Giving kids pocket money | ASIC's Money Smart. Canberra: ASIC. Retrieved from www.moneysmart.gov.au/life-events-and-you/families/teaching-kids-about-m...

Connolly, C. (2014). Measuring Financial Exclusion in Australia. Centre for Social Impact (CSI) - University of New South Wales, for National Australia Bank. Retrieved from www.nab.com.au/content/dam/nabrwd/documents/reports/financial/2014-measu...

Dwairy, M. (2010). Parental inconsistency: A third cross-cultural research on parenting and psychological adjustment of children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(1), 23-29.

Edwards, B. (2014). Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. Family Matters, 95, 5-14.

Financial Planning Association of Australia (FPA). (2018). Share the dream: Research into raising the invisible-money generation. Sydney: FPA. Retrieved from www.smsfassociation.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/FPA-Share-the-Dream-R...

Gudmunson, C.G., & Danes S.M. (2011). Family Financial Socialization: Theory and Critical Review. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32, 644-667 DOI 10.1007/s10834-011-9275-y

Hoeve, M., Stams, G.J., van der Zouwen, M., Vergeer M., Jurrius K., & Asscher, J. J. (2014). A systematic review of financial debt in adolescents and young adults: prevalence, correlates and associations with crime. Plos One, 9(8).

Hornyák, A. (2015). Attitűdök és kompetenciák a középiskolás diákok, mint potenciális banki ügyfelek körében. (Attitudes and competencies among high school students as potential bank customers.) Doctoral Thesis, University of West Hungary.

Kidwell, B., Brinberg, D., & Turrisi, R. (2003). Determinants of money management behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33(6), 1244-1260.

Kim, J., LaTaillade, J., & Kim, H. (2011). Family process and adolescents' financial behaviors of adolescents. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32, 668-679.

Lewis, A., & Scott, A. (2000). The economic awareness, knowledge and pocket money practices of a sample of UK adolescents: A study of economic socialization and economic psychology. Children's Social and Economics Education, 4, 34-46.

Luksander, A., Németh E., & Zsótér, B. (2017). Financial personality types and attitudes that affect financial indebtedness. International Journal of Social Science and Economic Research, 2(9).

Lusardi, A., Mitchell, O. S., & Curto, V. (2010). Financial literacy among the young. The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 44(2), 358-380.

Nagy, P., & Tóth, Z. (2012). Értelem és érzelem. A lakossági ügyfelek gazdasági magatartása és a bankok- kal kapcsolatos attitűdjei. (Sense and sensibility: Retail customer behaviours and attitudes towards banks.) Hitelintézeti Szemle, (Financial and Economic Review), 11, 13-24.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). (2014). PISA 2012 . Retrieved from passthrough6.fw-notify.net/download/609293/http://www.oecd.org/pisa/keyfindings/PISA-2012-results-volume-vi.pdf

Otto, A. (2009). The Economic Psychology of Adolescent Saving (Thesis). Retrieved from ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/bitstream/handle/10036/83873/OttoA.pdf

Parker, M. (2019). Dr Daryl Collins: Shadow finance is going digital and it's good. Retrieved from financialcapability.gov.au/posts/dr-daryl-collins-shadow-finance-is-going-digital/

Rinaldi, E., & Bonanomi, A. (2011). Adolescents and money: values and tools to handle the future. Italian Journal of Sociology of Education, 3(3).

Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research. (1997). Child development supplement for primary caregiver of target child child booklet. Ann Arbor, Michigan: The University of Michigan, Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research. Retrieved from psidonline.isr.umich.edu/cds/questionnaires/cds-i/english/PCGchild.pdf

Thomson, S., & De Bortoli, L. (2017). PISA 2015: Financial literacy in Australia. Melbourne: Australian Council for Educational Research. Retrieved from www.moneysmart.gov.au/media/560520/pisa2015_financialliteracyreport.pdf

Worthington, A. C. (2016). Financial literacy and financial literacy programmes in Australia. In: Harrison T. (Ed.), Financial literacy and the limits of financial decision-making. Melbourne: Palgrave Macmillan.

1 The terms 'financial literacy' and 'financial capability' tend to be used interchangeably but financial capability is increasingly preferred internationally. In Australia, financial capability is used by the Australian Securities & Investments Commission (ASIC), which is Australia's corporate, markets, financial services and consumer credit regulator.

2 The chapter does not examine young people's knowledge and understanding of financial language, as this information was not collected when LSAC children were 16-17 years old.

3 A summary of current understanding of financial skills, attitudes and money management among the Australian general population can be found in Worthington (2016).

4 Only 32 16-17 year olds in Wave 7 of LSAC were not living with their parents.

5 The 2018 FPA Survey showed similar results - parents stated that children were just as likely to save their pocket money for no particular reason (36%) as they were to spend it on small day-to-day purchases (36%), with the remaining 28% saving their money for larger items (FPA, 2018).

Acknowledgements

Featured image: © GettyImages/travellinglight