Adolescent injury

Adolescent injury

Snapshot Series - Issue 3

What do we know?

Injury is the leading cause of death and a major cause of disability among Australian adolescents. Often believed to be the consequence of random events, injuries are largely preventable. Much of what we currently know about adolescent injury is based on hospital emergency and admission data. However, not all injuries require hospital treatment, so the true extent of injury within the community is likely to be underestimated. Longitudinal studies that collect information on young people's experiences of injury at multiple time points can help us to better understand how and where injuries happen and identify factors that might increase the risk of injury at different ages.

What can we learn?

Using data from Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC), this snapshot looks at 16-17 year olds' experiences of injury, with a focus on their most serious injury within the previous two years. Injuries did not have to result in hospital treatment to be included in the analyses. Three main questions are addressed: (1) How common is injury among Australian adolescents? (2) What is the nature of adolescent injuries (type, place, cause, person treating)? (3) What personal and environmental factors increase the risk of adolescent injury?

In focus

In 2016, when aged 16-17, study adolescents reported the number of injuries they had experienced in the previous two years that had resulted in them missing two or more days of school or work. Further details were collected about what they considered to be their most serious injury during this period, such as injury type, cause, where it had happened and who provided treatment.

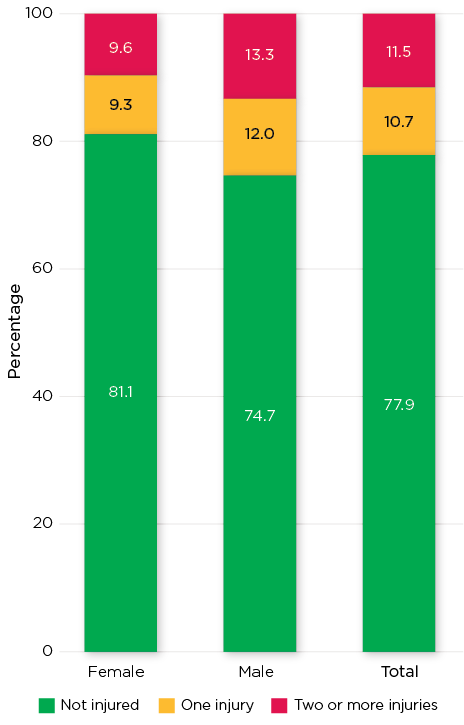

How common is adolescent injury?

Injury was common among adolescents, with higher rates for males. In 2016, more than one in five (22%) 16-17 year olds reported being injured in the previous two years (Figure 1). This equates to 53,512 Australian adolescents sustaining a significant injury or injuries.

More males than females had been injured (25% vs 19%). Similar gender differences have been found in other injury research using hospital admission and mortality data to examine rates of injuries among this age group.

It was common for injured adolescents to report having been injured multiple times. Over half (52%) of injured adolescents (11% of all adolescents) had been injured on multiple occasions in the previous two years. Around one in eight (13%) (3% of all adolescents) had sustained five or more injuries during this period.1

Figure 1: Proportion of adolescents aged 16-17 years who reported injury in the previous two years

Notes: Adolescent self-report at age 16-17

Source: LSAC K cohort, Wave 7, weighted. n = 1,451 for female, n = 1,498 for male, n = 2,949 for total

What is the nature of adolescent injuries?

Adolescents were asked further questions about their recent injury (or their most serious injury if they had had multiple injuries). Questions included cause of injury; type of injury; where the injury happened; who treated the injury and the number of days of school or work missed due to injury.

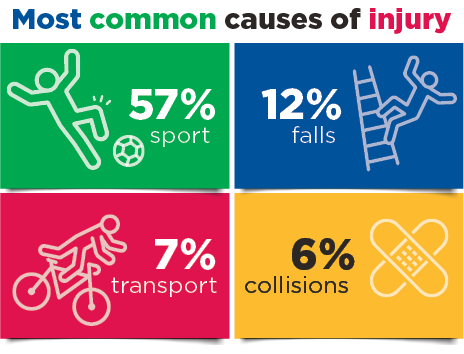

Cause of injury

Playing sport was the most common cause of injury, accounting for over half of all injuries.2 Males were more likely than females to have sustained an injury playing sport (61% of injuries to males were caused by sport vs 51% of injuries to females).

Other causes of significant injury were much less prevalent, with the next most common causes being falls, transport-related injuries (including car, motorbike, bicycle and pedestrian injuries) and collisions.

Adolescents were not asked whether their injuries were intentional or unintentional. While not directly comparable, parent survey responses indicated that 95% of injuries experienced by their children aged 16-17 in the previous year were unintentional.

Because sports injuries were the most common cause of injury among adolescents and accounted for more than 50% of all injuries, results are reported separately for sports and non-sports injuries throughout the remainder of the snapshot. It should be noted that 'non-sports injuries' include a wide range of causes (e.g. falls, transport-related causes, animal contact, collision with or being struck by a person or object).

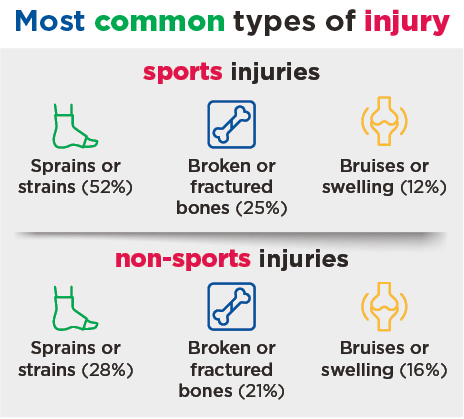

Type of injury

The types of injuries sustained playing sport and in other settings differed somewhat, with a greater range of injury types being reported in non-sports settings.3

Regardless of injury cause, the most common types of injuries were sprains or strains and broken or fractured bones. Around one in seven injury events (14% of sports and 15% of non-sports) involved multiple types of injury. Gender differences in the severity of injuries were observed: males were more likely to experience broken or fractured bones (e.g. 33% of sports injuries to males involved broken or fractured bones, compared to 12% of sports injuries to females) and females were more likely to sustain sprains and strains (63% of sports injuries to females involved sprains or strains, compared to 45% of sports injuries to males). Six per cent of sports injuries and 4% of non-sports injuries involved concussion.

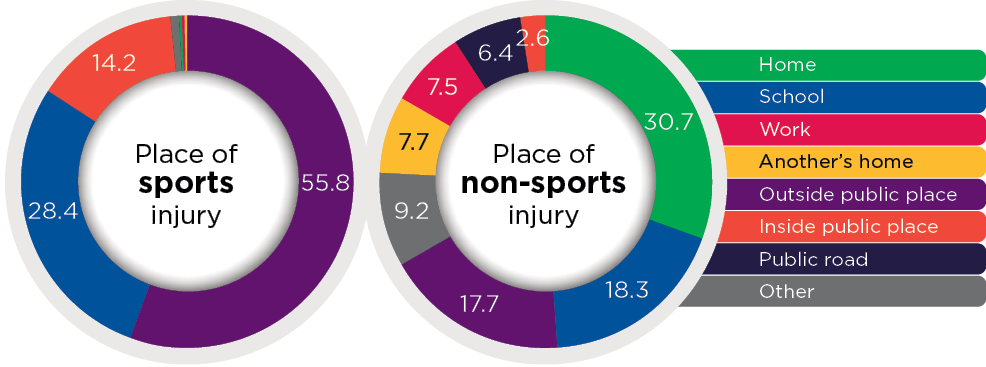

Where the injury happened

Adolescents sustained non-sports injuries in a wider range of locations than sports injuries.4 Nearly all sports injuries happened in one of three places: an outside public place (56%), school (28%) or an inside public place (14%). While non-sports injuries happened in a range of locations, the greatest number were at home (31%) or at school (18%). No gender differences were found.

Figure 2: Place where injuries happened, sports injuries and non-sports injuries

Notes: Respondents were asked to consider their most serious injury in the past two years. 'Other' injury locations were unspecified. 'Outside public place' includes areas such as playgrounds, sportsgrounds, beaches or public parks and excludes roads. 'Inside public place' includes areas such as gyms, indoor sports centres or shopping centres.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Wave 7, weighted. n = 387 for sports injury, n = 262 for non-sports injury

Who treated the injury?

A wide range of people treated adolescent injuries. Most injuries (69% of sports-related and 62% of non-sports-related) were treated outside a hospital environment. While it was common for adolescents to seek treatment from medical professionals, other people such as parents, teachers, coaches and allied health professionals were also often involved in injury treatment.5

Sports injuries were most commonly treated by a:

- medical specialist (32% of sports injuries)

- doctor or nurse at hospital (31%)

- doctor or nurse at a GP clinic (28%)

- coach or teacher (19%).

27% of sports injuries were treated by multiple people.

Non-sports injuries were most commonly treated by a:

- doctor or nurse at hospital (38% of non-sports injuries)

- doctor or nurse at a GP clinic (35%)

- medical specialist (20%)

- parent (18%).

35% of non-sports injuries were treated by multiple people.

Days of school or work missed

Non-sports injuries were associated with higher absenteeism than sports injuries. On average, approximately four days of school or work were missed due to a non-sports injury, compared to three days for sport injuries.6 No gender differences were found.

More than a quarter (26%) of adolescents who had experienced a non-sports injury had missed more than 10 days of school or work due to the injury within the past two years, compared to about one in six (17%) adolescents who had sustained sports injuries.

Who is more likely to be injured?

A range of factors were associated with an increased risk of injury among adolescents. A history of prior injury (between ages 12-15) was related to a markedly increased risk of both sports and non-sports injuries at 16-17 years. Compared to those with no prior injury, adolescents with a prior injury were at a 1.7 times greater risk of sustaining a sports injury (17% vs 10%; Figure 3) and a 1.8 times greater risk of having a non-sports injury (14% vs 8%; Figure 4), even after accounting for a broad range of other factors associated with injury risk (see supplementary materials for details).7

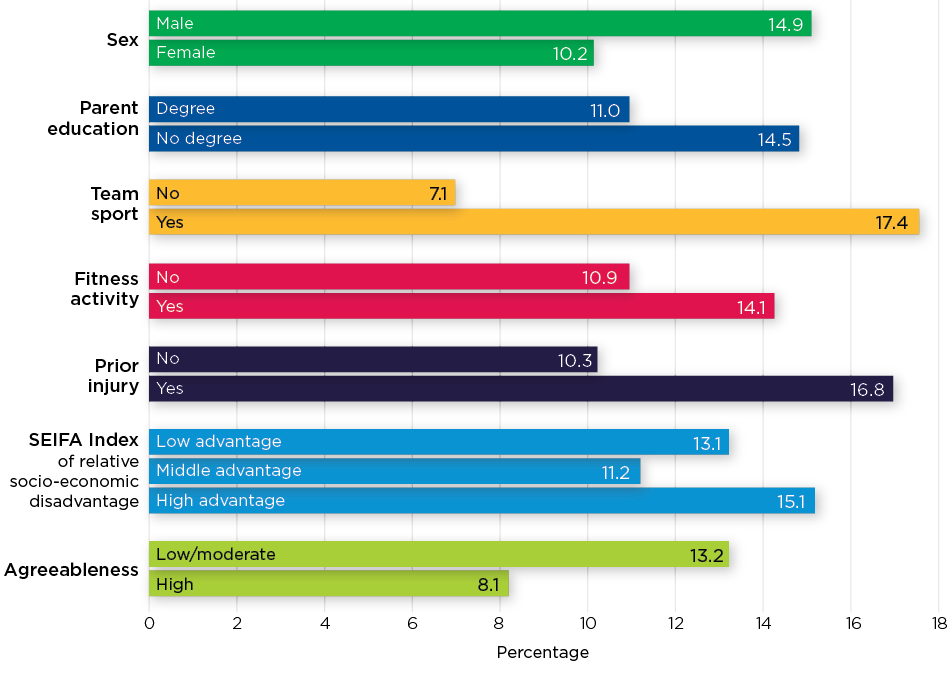

Figure 3: Percentage of adolescents with a sports injury, by adolescent characteristics

Notes: Percentages are predicted from a multivariate logistic regression model including all variables shown as well as: remoteness area of residence, equivalised parent income, extraversion, conscientiousness, neuroticism, openness personality traits, individual sports participation, school sector, employment, alcohol use and parent monitoring. 'Team sport' refers to past week participation in team sports at age 14-15. 'Prior injury' refers to any past year report of injury requiring medical attention at age 12-13 and/or 14-15. SEIFA = Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 5-7, unweighted. n = 2,096

Other factors related to the risk of adolescent sports injuries were:

- being male (1.5 times higher risk than being female)

- having parents who have not completed a tertiary degree (1.3 times higher risk than having degree-educated parents)

- participation in team sports (2.5 times higher risk than non-participation)

- participation in fitness activities (1.3 times higher risk than non-participation)

- living in an area of high economic advantage (SEIFA) (1.3 times higher risk than living in an area of middle economic advantage)

- having a low/moderate score for the agreeableness personality trait (1.6 times higher risk than high score).

Figure 4: Percentage of adolescents with a non-sports injury, by adolescent characteristics

Notes: Percentages are predicted from a multivariate logistic regression model including all variables shown as well as: sex, remoteness area of residence, SEIFA index, extraversion and agreeableness personality traits, individual sports participation, fitness activity participation, risky driving and alcohol use. Prior injury refers to any past year report of injury requiring medical attention at age 12-13 and/or 14-15.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 5-7, unweighted. n = 2,022

In addition to prior injury, other factors related to adolescent non-sports injuries were:

- living in a low-income family (1.6 times higher risk than living in a middle-income family)

- having parents who have not completed a tertiary degree (1.4 times higher risk than having degree-educated parents)

- not being in school (1.6 times higher risk than if attending a government school)

- employed full-time or part-time (1.4 times higher risk than not in employment)

- non-participation in team sports (1.7 times higher risk than team sport participation)

- low monitoring (supervision) of adolescent's activities by parents (1.4 times higher risk than moderate or high monitoring)

- having the following personality traits: high neuroticism (1.5 times higher risk), high openness (1.5 times higher risk) and low/moderate conscientiousness (1.6 times risk).

Relevance for policy and practice

These findings show that adolescent injury is relatively common and can have significant impacts on school and work participation, highlighting the importance of injury prevention to improving adolescent health. The findings suggest:

- Further work is needed to reduce injury prevalence and risk in team sports settings, particularly for males. The National Injury Prevention Strategy 2020-2030 (draft) 8 provides a number of recommendations about how this may be achieved. These include supporting sports clubs and schools to develop, implement and enforce safety policies and practices, compulsory use of relevant protective equipment, rules for safe play and accreditation of coaches and coaching standards.

- Intervention near the time of injury may reduce the risk of re-injury. In line with other research, findings showed that adolescents who had been injured were at higher risk of future injury. Targeted and individual interventions for those who have been injured may prevent future injuries.

- Further investigation and tailored services and programs for youth from families with low education and/or resources may reduce the risk of non-sports injuries. An association between socio-economic disadvantage and injury is recognised in the National Injury Prevention Strategy 2020-2030 (draft). All efforts to redress inequities in education, employment, income and housing are likely to reduce injury risk in low socio-economic status families. Addressing these social and cultural determinants will also lead to improved access to health information and health services, which will improve recovery after injury.

- Injury prevention resources would be most effective if tailored to a range of audiences. As adolescent injuries take place in different settings and most do not require hospital treatment, it is important to tailor injury prevention and management to a range of targets. This may include sports coaches, teachers, GPs, physiotherapists, dentists and parents.

- Home was the most common setting for adolescent non-sports injuries and low parental monitoring increased injury risk. These findings highlight the importance of interventions aimed at reducing risks within the home environment and involving parents in injury prevention efforts.

- Strategies to reduce injuries among working adolescents may be helpful given the high numbers of adolescents in full- or part-time employment and their increased risk of injury. These strategies may include improving workplace safety through health and safety training, ensuring tasks are developmentally appropriate, and providing adequate supervision. Additionally, prevention efforts could address non-workplace factors such as fatigue or substance use, which may lead working adolescents to be at higher risk of injury.

Potential of the Growing Up in Australia study

Data from Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) provide comprehensive and useful insights into adolescent injuries, including information about the substantial number of injuries not requiring hospital treatment. The broad range of contextual information across childhood available in LSAC provides a comprehensive picture of the circumstances that lead to injury, informing prevention efforts. Further follow-up of the LSAC sample will continue to provide details of injury and re-injury as adolescents mature into adults, as well as ongoing problems arising from injury. For example, the following questions could be investigated:

- What are the individual and environmental factors early in childhood that place adolescents at risk of - or protect against - adolescent injury?

- Are there critical developmental ages and stages for intervention to reduce childhood and adolescent injury?

- What places young adults at risk of injury?

- What are the lasting impacts of adolescent injury in terms of physical health, learning and economic and social participation?

Further details

Technical details of this research, including descriptions of measures, detailed results and bibliography are available to download as a PDF [200 KB]

About the Growing Up in Australia snapshot series

Growing Up in Australia snapshots are brief and accessible summaries of policy-relevant research findings from Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC). View other Growing Up in Australia snapshots in this series.

1 Full results are available in Table S1 of the supplementary materials.

2 Full results are available in Table S2 of the supplementary materials.

3 Full results are available in Table S3 of the supplementary materials.

4 Full results are available in Table S4 of the supplementary materials.

5 Full results are available in Table S5 of the supplementary materials.

6 Full results are available in Table S6 of the supplementary materials.

7 Full results are available in Table S7 of the supplementary materials.

8 www.health.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/national-injury-prevention-strategy-2020-2030-0

Acknowledgements

Authors: Dr Tracy Evans-Whipp and Suzanne Vassallo

Series editors: Dr Galina Daraganova and Dr Bosco Rowland

Copy editor: Katharine Day

Graphic design: Lisa Carroll

This snapshot benefited from academic contributions from Kelly Hand and Dr Jennifer Prattley.

This research would not have been possible without the invaluable contributions of the Growing Up in Australia children and their families.

Website: growingupinaustralia.gov.au

Email: [email protected]

The study is a partnership between the Department of Social Services, the Australian Institute of Family Studies and the Australian Bureau of Statistics, and is advised by a consortium of leading Australian academics. Findings and views expressed in this publication are those of the individual authors and may not reflect those of the Australian Institute of Family Studies, the Department of Social Services or the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Featured image: © GettyImages/SolStock

Publication details

Evans-Whipp, T., & Vassallo, S. (2021). Adolescent Injury (Growing Up in Australia Snapshot Series - Issue 3). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.