Adolescents combining school and part-time employment

Adolescents combining school and part-time employment

Snapshot Series - Issue 6

What do we know?

Many Australian school students balance school with part-time work commitments. Australia has one of the highest rates of combining work and study among OECD countries. Researchers have identified positive and negative aspects to combining paid employment with school. Having a job can develop skills and a range of positive behaviours including dependability, diligence, confidence and independence. On the other hand, employed students - particularly when they work for longer hours - may face time pressures and other stresses from the need to balance work commitments with study and other aspects of their lives. This is called 'work-life interference'.

What can we learn?

This snapshot examines the working lives and employment histories of young Australians in their secondary school years. It investigates possible interference with social activities, organised activities, health and study that students in paid employment might experience. An improved understanding of which student and job characteristics are linked to work-life interference can be used to guide students at the start of their working lives.

The snapshot addresses three main questions: (1) How do patterns of paid employment change for students between the ages of 12 and 17? (2) What are the characteristics of employed students aged 16-17 and what are their jobs like? (3) What proportion of working 16-17 year olds report work-life interference, and what job characteristics relate to work-life interference?

In focus

Adolescents in the secondary school years are the focus of this snapshot. This snapshot reports on those who were attending secondary school at age 16-17 1 (Wave 7; 2016) and who reported on their paid employment. Study adolescents were asked about their current employment and to rate how much their job demands and responsibilities interfered with their study, their social activities, their health and their ability to take part in organised activities (e.g. sports). They also rated the quality of their current job by answering questions about control and flexibility, demands and complexity, and security. Employment information collected at ages 12-13 and 14-15 are also examined.

How do patterns of paid work change between the ages of 12 and 17?

On average, students are more likely to take on paid work and work longer hours as they get older. However, these population averages can mask the diverse employment histories of individual students. Patterns of paid work between the ages of 12 and 17 can differ in terms of the age at which a student might start work, the number of hours that they work, and the extent to which a student might move in and out of employment as they get older. The focus of this snapshot is on students who were working at age 16-17 and, in this section, we show how they have experienced different pathways in to employment at that age.

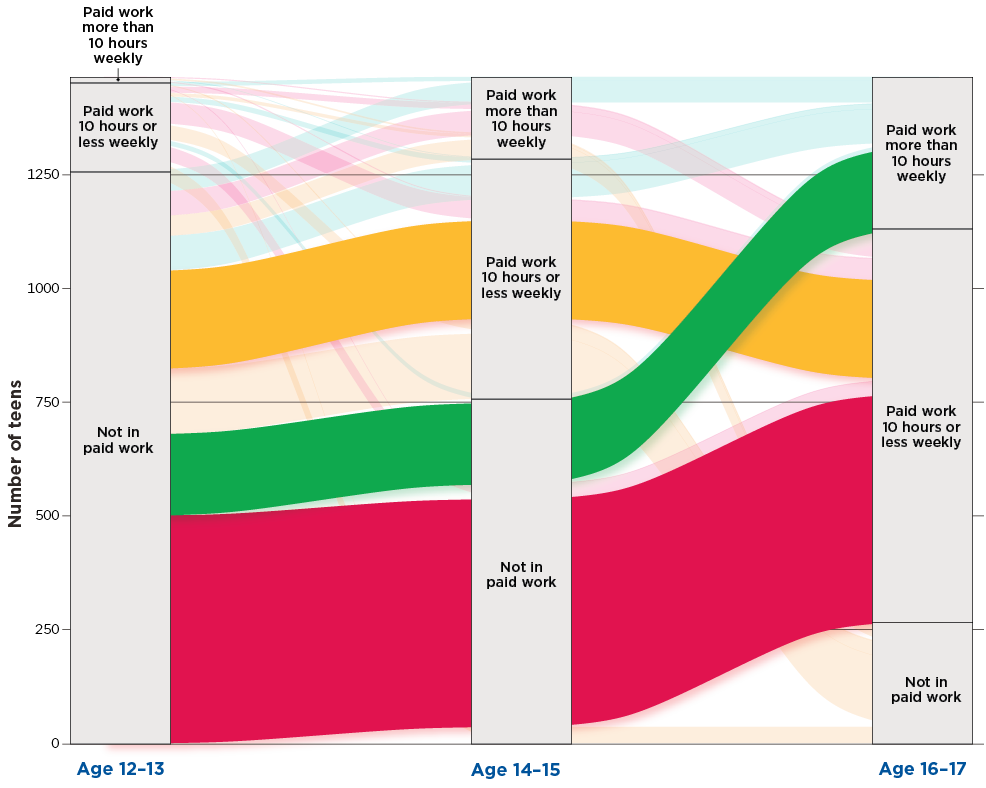

We classified paid employment in to less than or more than 10 hours a week and examined the work histories of 16-17 year old students who had reported working at some point since the age of 12-13. Those who did not have employment data available for each occasion (i.e. at ages 12-13, 14-15 and 16-17) were removed from this part of the analysis. Figure 1 is a visual depiction of the varied and complex employment histories that were analysed, and highlights the three most common pathways taken by students in to paid work at 16-17.2

Contrary to what might be expected, students didn't necessarily increase their time in employment gradually as they got older. We could expect students to move from not working at 12-13 to working for less than 10 hours at 14-15, and then increase their hours to work for more than 10 hours at 16-17. However, only 5% of the histories examined followed this pattern, with the majority of students showing a different pathway.

The green pathway in Figure 1 shows that 12% of students in the sample first reported working for more than 10 hours at age 16-17, after reporting as not working when they were younger. Just over one-third reported working for less than 10 hours at 16-17 with no recorded history of prior work (red pathway). Around 15% first reported work at age 14-15 for less than 10 hours per week and had that same level of hours at 16-17 (yellow pathway). Overall, movement in and out of paid work was common among students. For example, 13% were not working at 12-13, reported working at 14-15 (either less than or more than 10 hours of work per week) but reported not working at 16-17.

This analysis of individual employment patterns shows that, among students who have worked, patterns of participation and hours at work vary between the ages of 12-13 and 16-17. Many of those who are in paid employment at 16-17 have taken different routes to get there, rather than following a pattern of gradually increasing hours. In the next section of this snapshot the characteristics of these students who are working at 16-17 are explored in more detail, along with important features of their jobs.

Figure 1: Employment pathways of secondary school students

Notes: 'Paid work' is defined as work for money or other payment, and excludes unpaid work experience, voluntary work and household chores for pocket money. The sample is comprised of students who have employment data available at ages 12-13, 14-15 and 16-17 years and who have been in paid work at one or more ages and excludes unpaid work experience, unpaid work in family businesses, voluntary work and household chores for pocket money. Employment status at ages 12-13 and 14-15 was derived from parent report of whether the study adolescent worked in the past 12 months. Status at age 16-17 was determined by study adolescent report of current employment status.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 5-7, unweighted. n = 1,453

Characteristics of employed school students aged 16-17 and their jobs

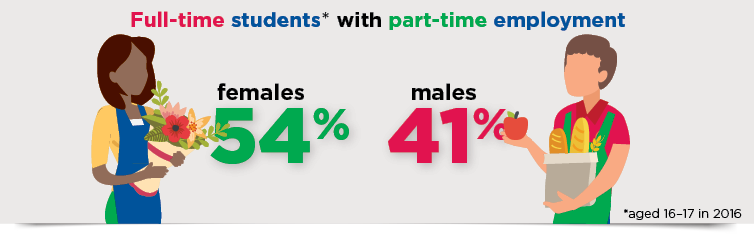

In 2016, 48% of secondary school students aged 16-17 were in part-time paid employment. A higher proportion of females (54%) were employed than males (41%).

Job characteristics

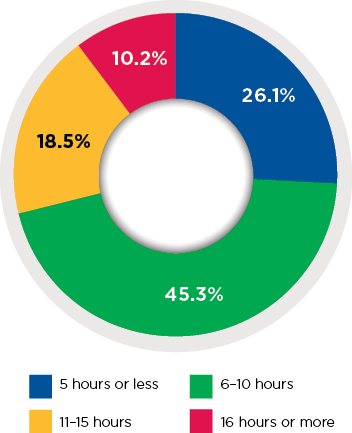

The majority (85%) of employed students had casual contracts. They were commonly employed in the food trade or food preparation (27% of males; 8% of females) and sales (26% of males; 49% of females) occupations. When asked about their reasons for working, most students gave financial reasons including working for spending money (44%) or to save up for something (42%).3 In terms of the timing and duration of work, most worked regularly on weekends (79% of males; 86% of females) and over 70% of employed students worked for 10 or less hours each week (Figure 2). On average, students worked between nine and 10 hours per week; males and females worked a similar number of hours.4

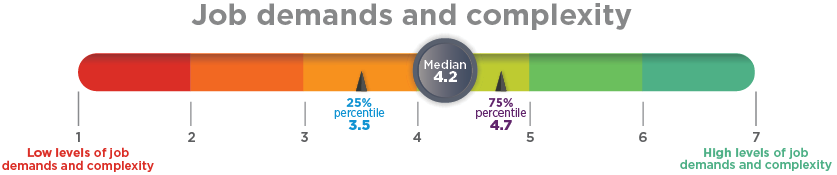

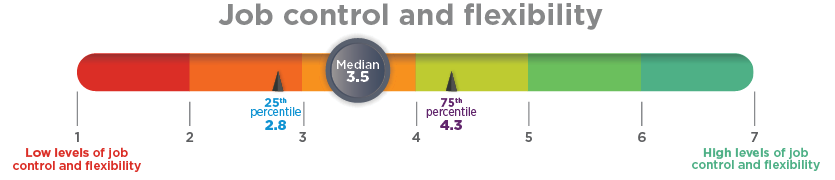

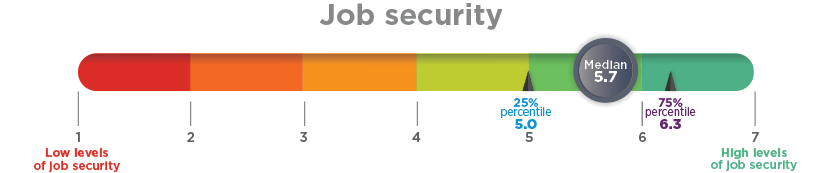

Students rated their jobs (on a scale of one (low) to seven (high)) on three aspects of job quality: 1) demands and complexity; 2) control and flexibility; 3) job security (Figure 3).5 'Demands and complexity' relates to the difficulty of the job and how hard and fast they have to work, with higher scores reflecting higher job demands and complexity. 'Control and flexibility' refers to issues such as freedom to decide how and when to do their work and flexibility in working and break times. Higher scores reflect greater levels of control and flexibility. Most students ranked their job on these two aspects of job quality towards the middle of the scale (median score for 'demands and complexity' was 4.2 and median score for 'control and flexibility' was 3.5), suggesting that they did not find the quality of their jobs too extreme in these aspects. 'Job security' indicates a student's concern about the future of their job, with higher scores reflecting greater job security. Most students rated their job towards the upper end of this scale (median score was 5.7), suggesting that they felt more, rather than less, secure in their employment.

Figure 2: Hours usually worked each week by students aged 16-17 years in paid work

Note: 'Paid work' is defined as work for money or other payment, and excludes unpaid work experience, voluntary work and household chores for pocket money.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Wave 7, weighted; n= 1,236

Figure 3: Job quality ratings by students aged 16-17 years in paid work

Notes: 'Paid work' is defined as work for money or other payment, and excludes unpaid work experience, voluntary work and household chores for pocket money. Median scores are the 50th percentile or centre of the distribution.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Wave 7, unweighted. n = 1,236

Student characteristics

Students in paid employment at age 16-17 differed from those who weren't in paid employment on a number of individual and family characteristics. We compared students who were not in work (52%) with those who were working either 10 or less hours per week (34%) or working more than 10 hours per week (14%). Those who combined school and work (in either of the two working hours categories) were more likely than non-working students to be female, live in rural or remote areas or come from an English-speaking background. Forty-four per cent of non-working students were female, compared to 57% of students who worked less than 10 hours per week and 55% of students who worked more than 10 hours, indicating an over-representation of females among the working student population.6

There is little evidence that students who work 10 or fewer hours per week come from a different socio-economic background to students who don't work. However, those who worked more than 10 hours per week tended to have lower socio-economic backgrounds. They were more likely than students who weren't employed to:

- live in lower or middle SES areas (13% of students working 10 or more hours per week lived in the most advantaged SEIFA quartile, compared to 25% of non-working students)

- attend government or Catholic (rather than independent) schools (12% of students working 10 or more hours per week attended independent schools, compared to 27% of non-working students)

- have parents with lower education levels (16% of students working 10 or more hours per week had parents whose highest qualification completed was Year 12 or less, compared to 12% of non-working students).

This group was also more likely than not-employed students to aspire to go on to trade or vocational training (rather than university) after school.

Work-life interference among students aged 16-17 years

Being employed during school years may increase school and social pressure for some adolescents. A substantial number of working students aged 16-17 reported that the demands and responsibilities of their paid employment interfered with other aspects of their lives.7 Students most commonly reported that paid work affected their social activities and least commonly affected their health:

- 38% reported interference with social activities

- 18% reported interference with organised activities, such as sports

- 15% reported interference with study

- 5% reported their job affected their health.

While each of these four domains reflect unique challenges and pressures for working students; overall, almost half (48%) reported interference between their paid work and at least one other aspect of their life. Similar proportions of males and females reported work-life interferences.

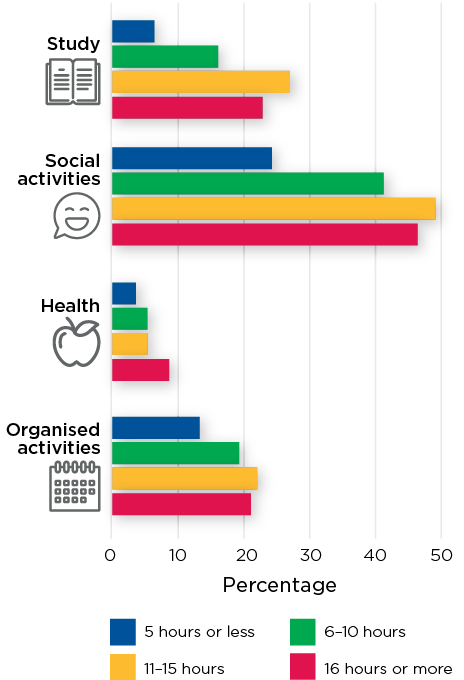

After accounting for a range of student-, family- and job-related factors, two key job-related factors were found to be particularly related to work-life interference: the number of hours worked, and the quality of the job.8

Number of hours worked

The number of hours worked is linked to the extent of work-life interference. For three of the work-life interference domains (study, social activities and organised activities), the proportion of students predicted to report interference increased as their working hours increased up to 11-15 hours per week (Figure 4). Working hours had the greatest impact on work-study interference, with those students working 11-15 hours per week over four times more likely to report interference with study than those working five hours or less (6% vs 27%). The proportion of students working 16 or more hours reporting interference in the study, social activities and organised activities domains was lower than for students working 11-15 hours, although this difference was minimal.

Although fewer students reported work-health interference, working hours were strongly related. Students working 16 hours or more per week were three times as likely than those working five hours or less to report interference with health (9% vs 3%).

Figure 4: Adjusted percentage of adolescents with various aspects of work-life interference, according to usual number of weekly hours in paid work

Notes: Percentages are predicted from multivariate logistic regression models including working hours, job quality, educational aspirations, school type, sex, Indigenous status, LOTE, SEIFA index, financial hardship, remoteness area of residence, parent employment and parent education.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Wave 7, unweighted. n = 1,152 for study model, n = 1,154 for social activity, health and organised activities models

Job quality

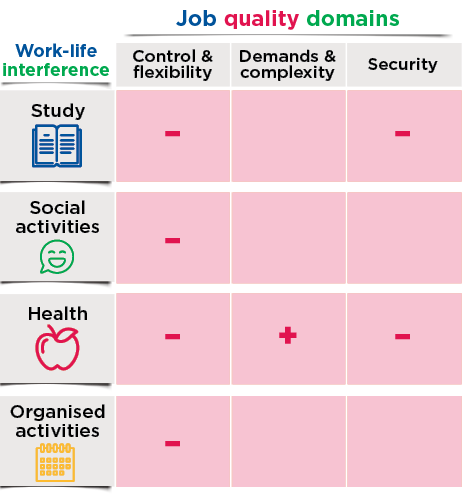

Students who reported they worked in higher quality jobs were less likely to report interference with study, health, and social and organised activities. Higher quality jobs were characterised by higher scores for 'control and flexibility' or 'job security' and lower scores for 'demands and complexity'. After accounting for the number of hours worked and other student, family and job characteristics, a statistically significant association was observed between each of these job quality sub-domains and at least one type of work-life interference (Figure 5).9 'Control and flexibility' affected interference across all four work-life domains, suggesting that this aspect of job quality has wide-ranging implications for students' lives.

Figure 5: Associations between job quality domains and work-life interference

Notes: + represents odds ratios greater than 1; - represents odds ratios less than 1. Associations were non-significant at the p < 0.1 level in blank cells. Results based on four separate multivariate logistic regression models predicting interference with study, social activities, health and organised activities. Models included working hours, job quality, educational aspirations, school type, sex, Indigenous status, LOTE, SEIFA index, financial hardship, remoteness area of residence, parent employment and parent education.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Wave 7, unweighted. n = 1,152 for study model, n = 1,154 for social activity, health and organised activities models

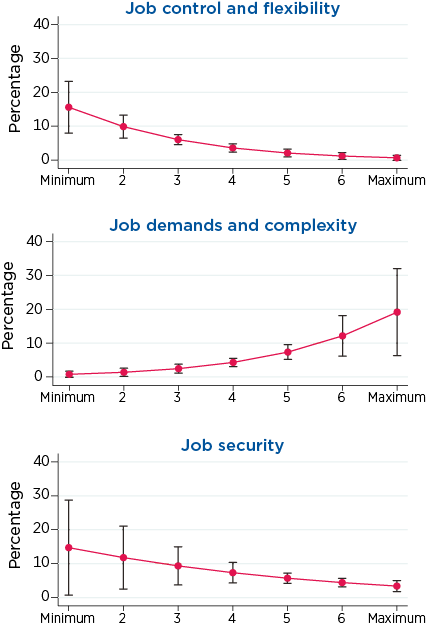

The association between job quality and work-life interference was particularly strong in the health domain: as ratings of 'control and flexibility' or 'security' increased, the odds of work-health interference decreased (Figure 6). The proportion of students estimated to report interference with health ranged from:

- 15.6% at the minimum end of the 'control and flexibility' scale to 0.7% at the maximum end

- 14.7% at the minimum end of the 'security' scale to 3.4% at the maximum end.

In contrast, an increase in the 'demands and complexity' of the job was associated with an increase in the likelihood of work-health interference (from 0.7% at the minimum end of the 'demands and complexity' scale to 19.1% at the maximum end).

Figure 6: Adjusted percentage of adolescents with work-life interference in the health domain, according to level of job quality sub-domains

Notes: Percentages are predicted from multivariate logistic regression models including working hours, job quality, educational aspirations, school type, sex, Indigenous status, LOTE, SEIFA index, financial hardship, remoteness area of residence, parent employment and parent education.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Wave 7, unweighted. n = 1,154

Relevance for policy and practice

This snapshot shows that it is common for upper secondary school students to take on paid employment, especially for females. It also reveals that many working students experience interference between their work and other aspects of their lives. The hours spent working and the quality of the job separately impact the extent to which work interferes with life. This suggests that we should not only consider the number of hours secondary students work for but also the type of roles and the work environments that they work in.

Therefore, in addition to the financial and other benefits of working, it is important for young people at the start of their working lives, as well as their parents or carers, to be aware of potential work-life interferences. The following suggestions for policy and practice across various domains could be considered:

- For parents - along with the commonly held positive view of teenage employment, it is important for parents and carers to be aware of the potential for paid work to cause disturbances in learning and health, especially if their children are working long hours, are in complex or demanding jobs, where they have minimal control or flexibility, or are in insecure employment.

- For schools - the secondary school curriculum and/or careers programs can help educate students on how to assess job quality and students' rights and responsibilities as paid employees. Schools can provide advice and guidance for students experiencing work-life interference. In light of the many different patterns of employment across the teen years, it would be beneficial to provide these resources regularly as students go through secondary school.

- For employers - it would be beneficial for employers to understand the needs of school-aged employees and provide them with sufficient job control, flexibility and security. For example, by being flexible around work schedules during exam periods or not rostering young people on late-night or long shifts.

- For governments - policy attention can be directed towards improving youth employment regulatory protections with respect to poor quality jobs and working conditions.

Potential of the Growing Up in Australia Study

Data from Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) provide detailed information about young people's study and employment characteristics in addition to a comprehensive range of demographic, family and other contextual factors.

Ongoing follow up of the LSAC sample will provide information about these students as they transition to the next phases of their lives. Further research questions that could be addressed with LSAC data include:

- Does experience of work-life interference relate to difficulties in students' physical wellbeing, mental wellbeing and learning?

- How do external supports from family, schools or employers help to reduce work-life interference?

- What are the benefits of paid employment during the secondary school years to young people's development, and which student and job characteristics predict these?

- What are the effects of combining part-time work and school on young people's transitions into tertiary education and/or employment?

Further details

Technical details of this research, including description of measures, detailed results and bibliography are available to download as a PDF [232.38 KB]

About the Growing Up in Australia snapshot series

Growing Up in Australia snapshots are brief and accessible summaries of policy-relevant research findings from Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC). View other Growing Up in Australia snapshots in this series.

This research would not have been possible without the invaluable contributions of the Growing Up in Australia children and their families.

Website: growingupinaustralia.gov.au

Email: [email protected]

The study is a partnership between the Department of Social Services, the Australian Institute of Family Studies and the Australian Bureau of Statistics, and is advised by a consortium of leading Australian academics. Findings and views expressed in this publication are those of the individual authors and may not reflect those of the Australian Institute of Family Studies, the Department of Social Services or the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

1 Around 16% males and 13% females were no longer attending secondary school at age 16-17.

2 The 15 most common patterns of employment are described in Table S1 of the supplementary materials.

3 Full results are available in Figure S1 of the supplementary materials.

4 Full results are available in Table S2 of the supplementary materials.

5 Items comprising each scale are available in the supplementary materials.

6 Full results are available in Table S3 of the supplementary materials.

7 Full results are available in Table S4 of the supplementary materials.

8 Full results are available in Table S5 of the supplementary materials.

9 Full results are available in Table S5 and Figures S2, S3 and S4 of the supplementary materials.

Acknowledgements

Authors: Dr Tracy Evans-Whipp, Dr Neha Swami and Dr Jennifer Prattley

Series editors: Dr Bosco Rowland and Dr Tracy Evans-Whipp

Copy editor: Katharine Day

Graphic design: Lisa Carroll

Featured image: © GettyImages/Hispanolistic

Publication details

Evans-Whipp, T., Swami, N., & Prattley, J. (2021). Adolescents combining school and part-time employment (Growing Up in Australia Snapshot Series - Issue 6). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.