Adolescents online

Adolescents online

Snapshot Series - Issue 5

What do we know?

Online communication and social networking sites (SNS) are central to the lives of young people. These media often help young people to strengthen 'offline' relationships and develop connections regardless of physical location. This can be particularly helpful for young people who lack social support or are at risk of social exclusion. However, there are concerns about the risks from cyberbullying and potential harmful effects on mental health. Little is known about how these risks vary for different groups of adolescents. Longitudinal research can provide insights into the online experiences of adolescents and how these may affect their mental health over time.

What can we learn?

Using data from Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC), this snapshot examines reports of online interactions from adolescents as they aged from 12-13 years to 16-17 years.1 This snapshot also looks at how these online interactions relate to adolescents' mental health, with a specific focus on the use of social networking sites (SNS). Two issues are examined in this snapshot: (1) adolescents' attitudes and behaviours online, and (2) connections between SNS use, cyberbullying and mental health across the secondary school years.

Key Findings

In focus

Young people reported on their online behaviour at ages 12-13 (2012), 14-15 (2014) and 16-17 (2016). At all three time points, young people were asked: 'How often do you use a computer or computer-like device to spend time on social networking sites?' Adolescents reported on their mental health (depression and anxiety symptoms) at these three time points. Information was also collected about their attitudes towards their online and offline interactions (at age 16-17), as well as their experiences of cyberbullying (at 14-15 and 16-17).

Given their higher risk of social exclusion, in this snapshot, we focus on the online interactions of particular groups of adolescents. These include adolescents with autism,2 those with long-term health conditions3 and adolescents experiencing mental health problems.

Adolescents' attitudes and behaviours online

Do adolescents spend more time with friends in person or via devices?

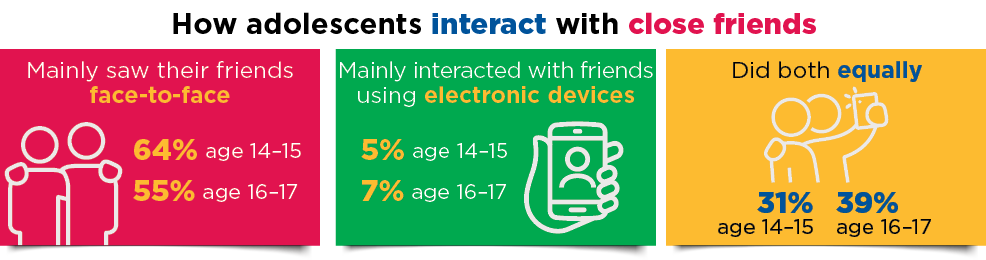

The majority of adolescents aged 14-17 spend more time interacting with close friends in person than via devices. However, the amount of time adolescents spend with close friends online increases with age.4 At age 16-17, more than a third reported spending equal amounts of time interacting online and offline with close friends.

Note: Percentages may not add to 100 at each age due to rounding.

Source: LSAC K cohort Wave 6-7, weighted. n =3,303 at age 14-15 and n = 2,927 at age 16-17.

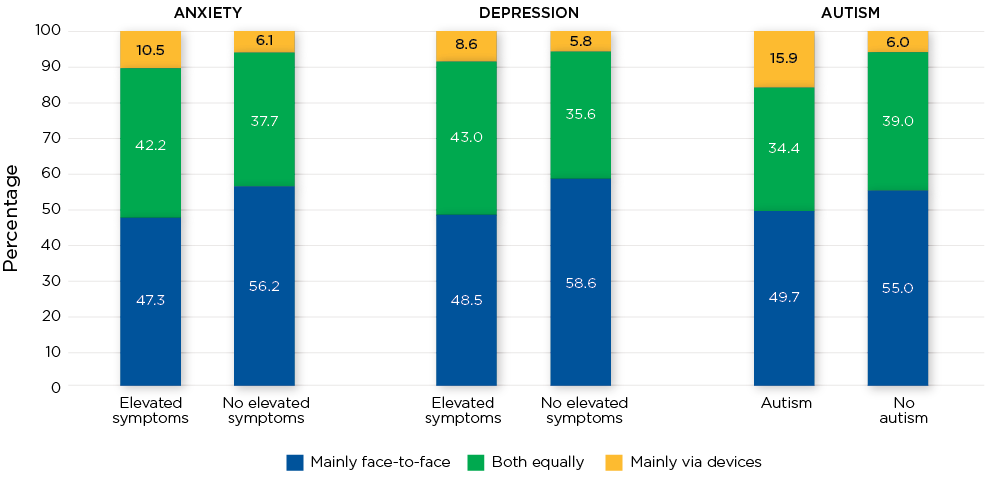

Adolescents with certain health conditions were greater users of electronic devices than adolescents with no conditions. Those with autism or elevated anxiety symptoms at age 16-17 were more likely to interact with close friends mainly through electronic devices (Figure 1). Similarly, adolescents with elevated depressive symptoms were less likely to interact with close friends mainly face-to-face.

Figure 1: Interaction with close friends at age 16-17 by subgroup

Notes: 'No autism' includes adolescents with no other long-term health conditions. See supplementary materials for more details on the measures of anxiety and depression.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Wave 7 (age 16-17), weighted. n = 518 for elevated anxiety symptoms; n = 2,421 for no elevated anxiety symptoms; n = 1,147 for elevated depressive symptoms; n = 1,765 for no elevated depressive symptoms; n = 84 for autism spectrum; n = 2,262 for no autism (and no long-term health conditions).

How comfortable do adolescents feel online?

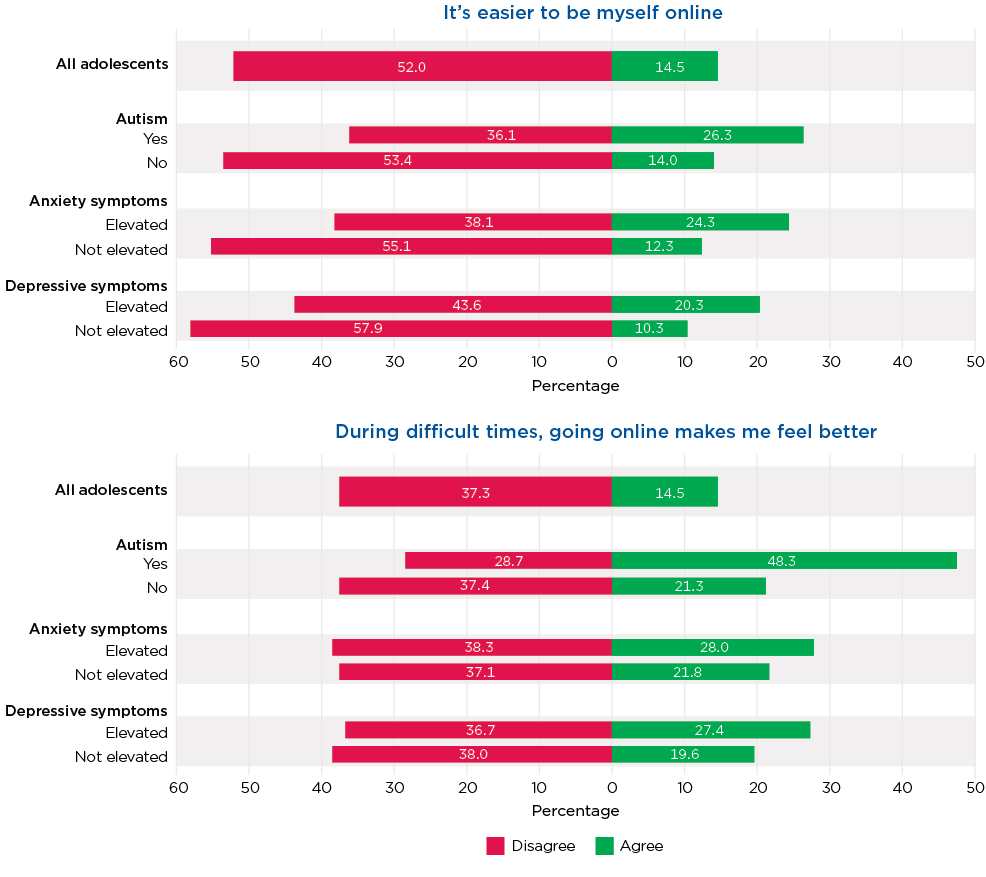

A small proportion of 16-17 year olds are more comfortable online than offline. Approximately 15% found it easier to be themselves online, and 11% found it easier to talk online about private things that they did not share with people face-to-face. This was similar for males and females.

Females were more likely than males to agree that 'during difficult times, I go online less often'. However, views on this issue were quite mixed. While almost a third of adolescents spent less time online when experiencing difficulties, 23% found going online made them feel better when going through difficult times. Although we do not know what types of activities young people were engaging in online, research suggests that adolescent males are more likely to spend time on online gaming whereas females are more likely to use social media.5

Although disagreement was more common, adolescents with autism, or elevated symptoms of anxiety or depression, were relatively more likely to agree that it was easier to be themselves online (Figure 2) (compared to those without autism, with low anxiety and low depressive symptoms). Similarly, young people with autism and adolescents with elevated depressive symptoms were more likely to agree that during difficult times, going online made them feel better (Figure 2), compared with adolescents without the relevant characteristic.6

Figure 2: Level of agreement with statements about 'being online' by specific groups of adolescents

Notes: 'Neutral' category was omitted in the figures. The category 'no autism' includes adolescents with no other long-term health conditions.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Wave 7, weighted. n = 87 for autism; n = 2,262 for 'no autism'; n = 525 for elevated anxiety symptoms; n = 2,421 for no elevated anxiety symptoms; n = 1,155 for elevated depressive symptoms; n = 1,765 for no elevated depressive symptoms.

Social networking sites, cyberbullying and mental health

How often do young people use social networking sites (SNS)?

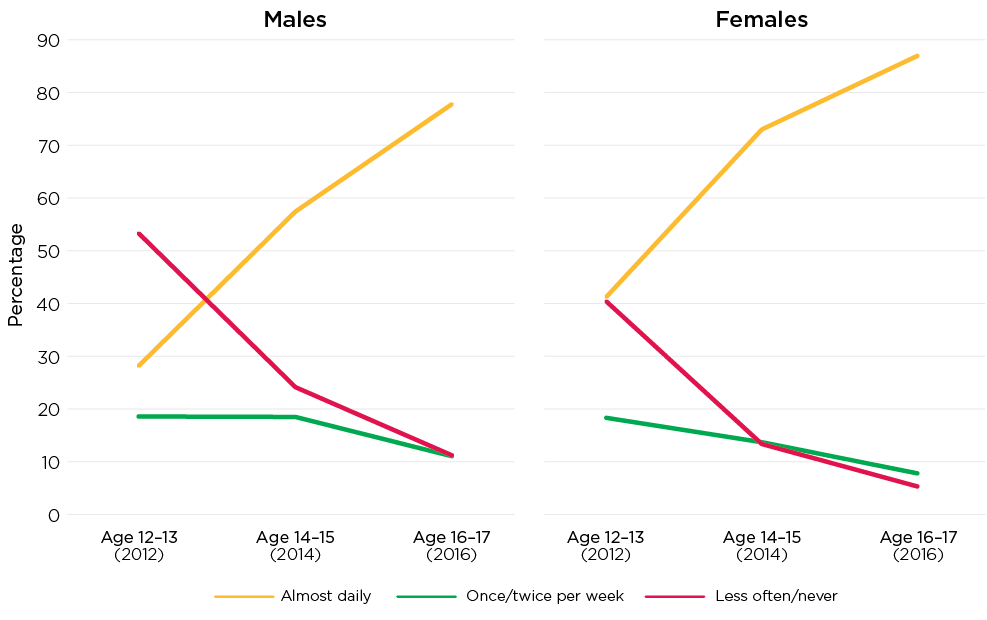

Use of SNS is common for the majority of 16-17 year olds. By this age most adolescents (78% of males and 87% of females) were using SNS almost daily. Females adopted SNS use earlier and their frequency of use was higher than males' at every age (Figure 3).

However, some adolescents are not as engaged with SNS. At age 16-17, close to a third of teens with autism (36%) reported that they never used SNS, and 8% of those with long-term health conditions and 7% of other adolescents reported that they were not daily users of SNS.

Figure 3: Frequency of use of social networking sites by sex between ages 12-13 and 16-17

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 5-7, weighted. n = 3,850 at age 12-13, n = 3,317 at age 14-15, n = 2,947 at age 16-17.

Is SNS use related to mental health?

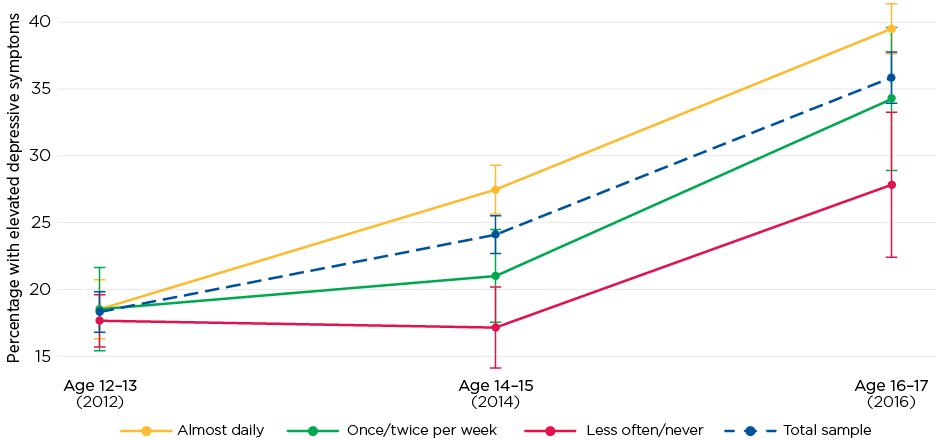

Increased frequency of SNS use over time is associated with greater levels of depressive symptoms, and this association is stronger at older ages (Figure 4).7 The risk of experiencing elevated depressive symptoms increased significantly among adolescents who went from using SNS weekly or less than weekly to almost daily over time. Increased frequency of SNS use was also associated with a higher risk of elevated anxiety symptoms.8

Figure 4: Mean trajectories of elevated depressive symptoms by frequency of SNS use from ages 12-13 to 16-17

Notes: Average trajectories based on multi-level mixed-effects logistic regression model of risk of elevated depressive symptoms (final model with time interaction). Models controlled for socio-demographic characteristics, temperament, relationships with peers and parents, parental mental health, experiences of bullying and cyberbullying.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 4-7 (ages 10-11 to 16-17).

Cyberbullying and mental health

Cyberbullying is a relatively common experience for adolescents. Cyberbullying refers to the use of technology, especially online forums, social media platforms and text messaging, to bully a person with the intent to hurt or intimidate them. This includes behaviours such as threats and name-calling. Approximately one quarter (25%) of adolescents between the ages of 14 and 17 reported having been the victim of cyberbullying in the past year.

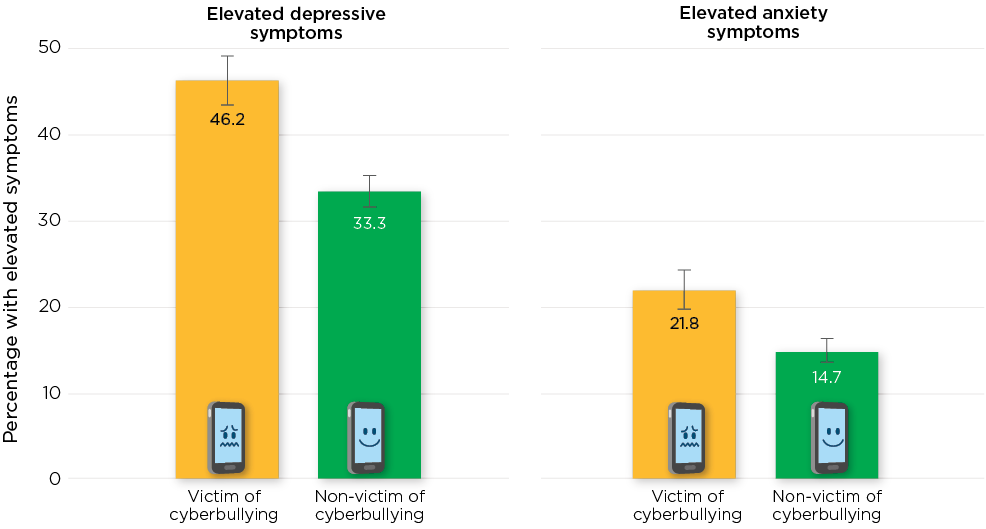

Adolescents who were victims of cyberbullying were more likely to report elevated depressive symptoms or elevated symptoms of anxiety (Figure 5).9 This risk did not vary among adolescents with autism or long-term health conditions.

Figure 5: Predicted percentage of adolescents with mental health problems by experiences of cyberbullying (age 16-17)

Notes: Predicted probabilities based on multi-level mixed-effects logistic regression models of depression (final model with time interaction) and anxiety (full model) from ages 12-13 to 16-17, controlling for socio-demographic characteristics, temperament, relationships with peers and parents, parental mental health, and SNS use. 95% confidence intervals are shown by the 'I' bars at the top of each column.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 4-7 (ages 10-11 to 16-17)

The changing technological environment

Since the current data were collected (between 2012 and 2016), the platforms young people are using to connect have changed substantially and digital devices such as mobile phones have become more readily available to adolescents, including access to multiple SNS mobile applications. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way that many young people interact, with many having to rely heavily on digital technologies to keep in touch with friends and family. Given the rapidly evolving nature of digital technologies, ongoing research into the safe and effective use of online platforms is needed.

Relevance for policy and practice

This snapshot shows that online communication plays a significant role in adolescents' lives and may provide benefits to some adolescents. These findings also add to a growing body of research suggesting that greater time online, particularly on social networking sites (SNS), may place young people at risk of harm, including mental health challenges. The findings suggest that:

- Further research on the mechanisms for the association between SNS and mental health is needed. Although no causal effects can be drawn from the present study, the findings align with emerging evidence showing that increased social media use may lead to poorer mental health.

- Online engagement appears to have benefits for some young people in terms of facilitating social connection and providing support during difficult times.

- Online safety and cyberbullying education programs are key. Providing young people with the skills to interact safely online and deal with cyberbullying is critical. In this context, schools have an important role to play in supporting young people to be safe online. The eSafety Commissioner website provides tools for schools to incorporate online safety into their curriculum, as well as trusted information for young people, parents and teachers.

- Given adolescents' increasing online connectivity, guidelines for balanced use of technology are likely to be beneficial. Creating family agreements or plans around use of technology, and SNS in particular, can support young people to safely engage in online interactions, while allowing time for other activities important for healthy development, such as sleep, exercise and face-to-face interactions.

Potential of the Growing Up in Australia study

Most research on online communication and mental health has been cross-sectional and in small non-representative samples. LSAC is one of the few large national studies collecting information on adolescents' wellbeing and online interactions in Australia. Furthermore, at age 16-17, LSAC collected detailed information on hours of internet use and online activities, in addition to the information presented in this snapshot. Analysis of these data can provide further insights into the risk factors for children to become heavy social media users in adolescence, and the mechanisms involved in the association between online behaviours and mental health outcomes. For example:

- What are the mechanisms by which online behaviours affect mental health? For instance, does it relate to reduced time spent on face-to-face interactions, exercise or sleep? Is it related to concerns about body image?

- What are the risk factors in childhood and early adolescence for high frequency of online interaction and social media use in the secondary school years?

- How do home and environmental risk factors at various stages of development impact on online activity?

Further details

Technical details of this research, including description of measures, detailed results and bibliography are available to download as a PDF [123.52 KB]

About the Growing Up in Australia snapshot series

Growing Up in Australia snapshots are brief and accessible summaries of policy-relevant research findings from Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC). View other Growing Up in Australia snapshots in this series.

This research would not have been possible without the invaluable contributions of the Growing Up in Australia children and their families.

Website: growingupinaustralia.gov.au

Email: [email protected]

The study is a partnership between the Department of Social Services, the Australian Institute of Family Studies and the Australian Bureau of Statistics, and is advised by a consortium of leading Australian academics. Findings and views expressed in this publication are those of the individual authors and may not reflect those of the Australian Institute of Family Studies, the Department of Social Services or the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

1 It should be noted that data were collected prior to the COVID-19 pandemic in which online usage and activities might have changed substantially.

2 We use person-first language (e.g. 'person with autism') in this snapshot. However, we acknowledge that individuals differ in how they prefer to be described and many people prefer identify-first language (e.g. 'autistic person'), reflecting the belief that autism is a core part of their identity. Includes autism, Aspergers or other autism spectrum.

3 The category 'long-term health conditions' includes children who have a condition that has lasted or is expected to last for at least 12 months that causes them to use medicine prescribed by a doctor, other than vitamins, or more medical care, mental health or educational services. Reported by the primary caregiver.

4 It is unclear how much of this increase is due to age-related factors versus a time-related effect to do with changes in technology, internet access and increased availability of electronic devices.

5 See, for example, Rhodes, A. (2017). Screen time and kids. What's happening in our homes? Australian Child Health Poll, Poll 7. The Royal Children's Hospital. www.rchpoll.org.au/polls/screen-time-whats-happening-in-our-homes and Su, W., Han, X., Yu, H., Wu, Y., & Potenza, M. N. (2020). Do men become addicted to internet gaming and women to social media? A meta-analysis examining gender-related differences in specific internet addiction. Computers in Human Behavior, 113. doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106480

6 Full results are available in Tables S1-S3 of the supplementary materials.

7 Full results are available in Table S4 of the supplementary materials.

8 Full results are available in Table S5 of the supplementary materials.

9 See Tables S4 and S5 in the supplementary materials.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

Authors: Dr Pilar Rioseco and Suzanne Vassallo

Series editors: Dr Tracy Evans-Whipp and Dr Bosco Rowland

Copy editor: Katharine Day

Graphic design: Lisa Carroll

This research would not have been possible without the invaluable contributions of the Growing Up in Australia children and their families.

Website: growingupinaustralia.gov.au

Email: [email protected]

The study is a partnership between the Department of Social Services, the Australian Institute of Family Studies and the Australian Bureau of Statistics, and is advised by a consortium of leading Australian academics. Findings and views expressed in this publication are those of the individual authors and may not reflect those of the Australian Institute of Family Studies, the Department of Social Services or the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Featured image: © GettyImages/FOTOGRAFIA INC.

Publication details

Rioseco, P., & Vassallo, S. (2021). Adolescents online (Growing Up in Australia Snapshot Series - Issue 5). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.