Alcohol use among teens allowed to drink at home

Alcohol use among teens allowed to drink at home

Snapshot Series - Issue 2

What do we know?

Although more young Australians are delaying their first alcoholic drink, many still begin drinking before 18. In addition to experiencing negative drinking-related outcomes such as injuries and mental ill-health, early alcohol use can lead to harmful drinking practices and alcohol use disorders later in life. Adolescent alcohol consumption can also adversely affect brain development. Identifying modifiable factors associated with adolescent alcohol use, such as parenting practices, is important for preventing alcohol-related harms among young people.

Prior to 2009, in Australia, official advice suggested that alcohol use was a 'normal' part of adolescent development, and that supervised alcohol consumption could reduce potential harm. Therefore, parents may choose to allow their underage teens to drink at home to help young people learn responsible drinking practices. However, with mounting evidence about the numerous risks of underage alcohol use, current National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) guidelines1 suggest delaying alcohol use until at least the age of 18.

What can we learn?

This snapshot uses data from Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) to answer three main research questions: (1) How many Australian teens are allowed to drink at home? (2) Does permission to drink at home result in teens drinking more and a greater risk of experiencing alcohol-related harm? (3) Which teens are more likely to be allowed to drink at home?

Media release

More than one in four adolescents under 18 years old allowed to drink at home

12 AUGUST 2021

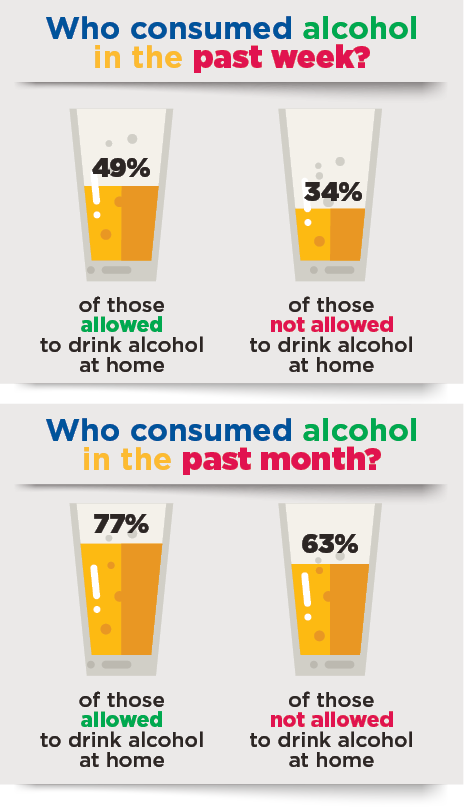

Among teens who had ever drunk alcohol, those with permission to drink at home were significantly more likely to have drunk in the past month (77%, compared to 63%) and in the past week (49%, compared to 34%).

News stories

- Parents warned against allowing teens to drink as study reveals underage alcohol use in Australia

- Quarter of 16-17 year olds drink at home

- Warning for parents who allow underage children to drink alcohol

In focus

Australian teens aged 16-17 years are the focus of this snapshot. For the first time in 2016 (Wave 7), parents were asked questions about whether they allowed their children to drink alcohol at home, and whether their children were allowed to take alcohol to parties or other social events. Since 2012 (Wave 5), study children have been asked whether they have ever drunk alcohol. If they have, they are asked further questions about their recent and current patterns of drinking and their experience of certain alcohol-related harms. For this snapshot, 'underage drinking' is defined as alcohol use before the age of 18, the legal purchasing age in Australia.

How many teens are allowed to drink at home?

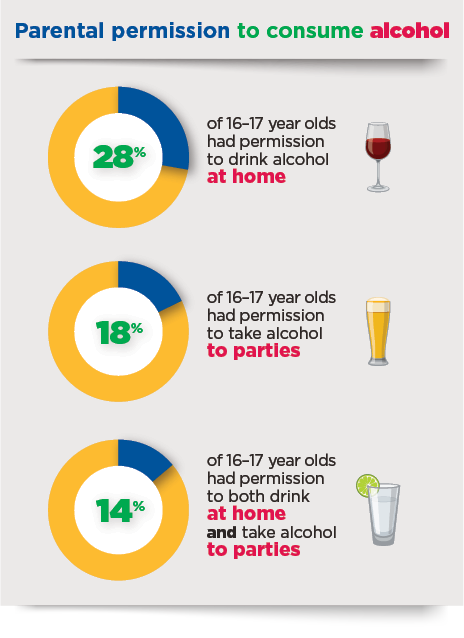

In 2016, just over one-quarter (28%) of Australian teens aged 16-17 had permission from their parents to drink at home. This was similar for females (29%) and males (27%). Parental reports indicate that, of the teens permitted to drink at home, most (70%) did so less frequently than monthly, and around 2% drank alcohol at home on at least a weekly basis. One-fifth (20%) had never drunk alcohol at home or had not done so in the past year, despite being allowed to.

These teens were first allowed to drink a full serve of alcohol at home at an average age of 16.0 years (SD = 1.5). This was similar for males (16.0) and females (15.9).

Close to one-fifth (18%) of teens aged 16-17 years had parents who allowed them to take alcohol to parties or social events. This group was mostly (75%) comprised of teens who were also allowed to drink at home. Again, there was little difference between female (19%) and male (17%) teens with regard to being allowed to take alcohol to parties/social events.

Does permission to drink at home result in teens drinking more?

In 2016, teens aged 16-17 years who were allowed to drink at home were more likely to have reported having ever drunk alcohol (88%) compared to those not permitted to drink at home (49%).

Recent and current alcohol use

Among teens who had ever drunk alcohol, nearly all (98%) had done so at least once in the past year. Most (69%) had drunk alcohol in the past month, and 40% in the last week.

Compared to teens without parental permission to drink at home, those with permission were significantly more likely to have drunk alcohol in the past month (approximately 20% more likely) and in the past week (almost 45% more likely).

Drinking quantity

The amount of alcohol recently drunk (at home or elsewhere) by teens permitted to drink at home was comparable to the amount drunk by those not permitted to drink at home. Among teens who had drunk any alcohol in the past week, those whose parents allowed them to drink at home had consumed an average of 6.5 standard alcoholic drinks in the past week (95% CI [5.7, 7.3]), compared to an average of 6.3 drinks consumed by teens not allowed to drink at home (95% CI [5.3, 7.3]).2

Are teens allowed to drink at home more likely to experience alcohol-related harms?

Alcohol use can lead to numerous types of harms, including negative physical, mental, financial and social outcomes such as:

- trouble at school or work the day after drinking

- arguments with family members

- alcohol-related injuries or accidents

- violence or involvement in a fight due to alcohol

- having sex with someone due to alcohol and regretting it later.

Teens whose parents permitted them to drink at home were significantly more likely to have ever experienced any alcohol-related harm (i.e. one or more of the above harms) compared to those not allowed to drink at home (23% vs 17%, respectively).

Which teens are more likely to be allowed to drink at home?

When taking a number of socio-demographic and psychosocial characteristics into account in a multivariable analysis, the following parental (primary parent/carer), familial and individual factors were found to be associated with an increased likelihood of teens aged 16-17 years being permitted to drink at home:3

- living in more socio-economically disadvantaged neighbourhoods:

- Around 30% of teens living in the most disadvantaged neighbourhoods (the lowest quartile of advantage) were allowed to drink at home, compared to 24% of those in the most advantaged neighbourhoods (the highest quartile).4

- residing in inner or outer regional areas compared to major cities in Australia:5

- Around 35% of teens in outer regional or remote areas were allowed to drink at home, compared to 30% of those in inner regional areas and 25% of those in major cities.

- being an only child:

- One-third (33%) of teens who were only children were allowed to drink at home, compared to 28% of those who were youngest children, and 26% of those who were the oldest child.

- having a younger primary parent/carer:

- Every one-year increase in primary parent/carer age was associated with a 2% decrease in the likelihood of parents allowing their teens to drink at home.

- having a less educated primary parent:

- Thirty-six per cent of teens with parents with a Year 12 education (maximum) were permitted to drink at home, compared to 24% of those with parents with a university education.

- residing with one biological parent and one step-parent (compared to two biological parents):

- Thirty-seven per cent of teens living with one biological parent and one step-parent were allowed to drink at home, compared to 27% of those with two biological parents and 26% of those living with a single parent.

Factors not significantly associated with permitting teens to drink at home included: sex of adolescent and primary parent, Indigenous status of adolescent, language background, and level of parental monitoring.

Associations with parental drinking patterns

When taking socio-demographic and psychosocial factors into account,6 having a primary parent/carer with a history of alcohol problems (as a child and/or as an adult) was not associated with allowing an adolescent to drink at home underage. However, having a primary parent who drank at all when their child was aged 14-15 years was significantly associated with allowing teens to drink at home when they were aged 16-17 years.

More frequent alcohol consumption by parents was associated with a greater likelihood of allowing teens to drink at home. When taking key characteristics into account (e.g. socio-economic status, family structure, parent age), each incremental increase in parental drinking frequency was associated with a 23% increase in the odds of parents allowing their 16-17 year old teen to drink at home, compared to parents who did not drink at all.

Relevance for policy and practice

These findings reveal that, in 2016, a significant proportion of parents allowed their teens aged 16-17 to drink alcohol at home. Given previous harm reduction recommendations, some Australian parents might think that if they allow their child to drink alcohol in moderation at home (such as having a beer or glass of wine at home with dinner), this will lead to a more responsible relationship with alcohol. However, greater rates of recent alcohol use and an increased likelihood of experiencing alcohol-related harms among those with permission to drink at home provide further evidence to support the NHMRC's guideline that children and people under 18 years of age should not drink alcohol, even in environments or circumstances that might be considered 'low risk'.

To this end, parents can reduce their child's risk of harm by encouraging them to delay drinking alcohol for as long as possible. Educating parents and their children about current national alcohol use guidelines and alcohol-related consequences among young people, such as via the media and schools, might help to address alcohol harms in Australia.

Potential of the Growing Up in Australia study

Understanding when and how teens start drinking, and changes to drinking patterns over time, is important for identifying opportunities for interventions to address alcohol-related harms in Australia. Changes to alcohol legislation warrant ongoing investigations of any resultant impacts on the drinking practices and experiences of young people. The ongoing nature of LSAC will allow us to monitor this. Specific research questions to answer using LSAC data include:

- How do changes to alcohol legislation (e.g. 'secondary supply' laws) affect the extent that children are provided with alcohol and their developmental trajectories?

- What types of family factors, such as family conflict, family discipline and family management, influence parental provision of alcohol to teens?

- What individual, family and lifestyle factors are associated with a delayed uptake of alcohol use among young Australians and a reduced likelihood of engaging in riskier alcohol consumption patterns?

Further details

Technical details of this research, including description of measures, detailed results and bibliography are available to download as a PDF [123.52 KB]

About the Growing Up in Australia snapshot series

Growing Up in Australia snapshots are brief and accessible summaries of policy-relevant research findings from Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC). View other Growing Up in Australia snapshots in this series.

1 The National Health and Medical Research Council's Australian Guidelines to Reduce Health Risks from Drinking Alcohol:

www.nhmrc.gov.au/health-advice/alcohol#download

2 Data on volume of alcohol consumed were only collected for the past week (see the supplementary materials).

3 For the full results see Table S1 of the supplementary materials.

4 This measure uses the SEIFA index of relative socio-economic disadvantage.

5 Areas are rated by the Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS).

6 For the full results see Table S1 of the supplementary materials.

Acknowledgements

Author: Dr Brendan Quinn

Series editors: Dr Galina Daraganova and Dr Bosco Rowland

Copy editor: Katharine Day

Graphic design: Lisa Carroll

This snapshot benefited from academic contributions from Kelly Hand, Dr Tracy Evans-Whipp and Suzanne Vassallo.

This research would not have been possible without the invaluable contributions of the Growing Up in Australia children and their families.

Website: growingupinaustralia.gov.au

Email: [email protected]

The study is a partnership between the Department of Social Services, the Australian Institute of Family Studies and the Australian Bureau of Statistics, and is advised by a consortium of leading Australian academics. Findings and views expressed in this publication are those of the individual authors and may not reflect those of the Australian Institute of Family Studies, the Department of Social Services or the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Featured image: GettyImages/master1305

Publication details

Quinn, B. (2021). Alcohol use among teens allowed to drink at home (Growing Up in Australia Snapshot Series - Issue 2). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.