Prosocial behaviours and the positive impact on mental health

Prosocial behaviours and the positive impact on mental health

Snapshot Series – Issue 9

What do we know?

Prosocial behaviours are any activities that have the aims of benefiting others or society. These behaviours can include volunteering, contributing to others’ wellbeing through acts of kindness, or helping those who are less fortunate. Prosocial behaviours differ from caring done out of necessity, such as caring for a sick significant other. Prosocial behaviours towards others are developmentally important, as they can help children and young people learn to take another person’s perspective, negotiate difference, and develop social and emotional skills.

Federal and state governments are actively promoting the importance of volunteering through the development of a National Strategy for Volunteering.

What can we learn?

This snapshot follows a nationally representative sample of children from age 4–5 years through to 16–17 years. We examine what effect, over time, the cultivation and/or promotion of informal (e.g. spontaneous and unstructured) and formal (e.g. structured and organised) prosocial behaviours has on poor mental health (emotional problems). Specifically, we examine the following: (1) To what extent are Australian children involved in informal prosocial behaviours, and does this change with age? (2) To what extent do symptoms of poor mental health change with age? (3) During the childhood and adolescent years, to what extent is engagement in prosocial behaviours and volunteering associated with improved mental health as they develop?

In focus

This snapshot reports on data collected across a 12-year period from parents in both of the LSAC cohorts. The study child’s primary parent reported on their child’s prosocial behaviours and their child’s mental health every two years between 2008 and 2018 for the B cohort (ages 4–5 years to 14–15 years) and between 2004 and 2016 for the K cohort (ages 4–5 years to 16–17 years). This was measured using the ‘Prosocial Behaviour’ and ‘Emotional Symptoms’ scales, respectively, in the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ).

Specifically, prosocial behaviour was assessed by summing responses to questions about five types of behaviour such as ‘sharing readily with others’ and ‘often volunteers to help others’ (see supplementary materials for more detailed information on this and other measures).

Volunteering was assessed by self-report in 2016 when children in the B cohort were 12–13 years old and the K cohort children were 16–17 years old.

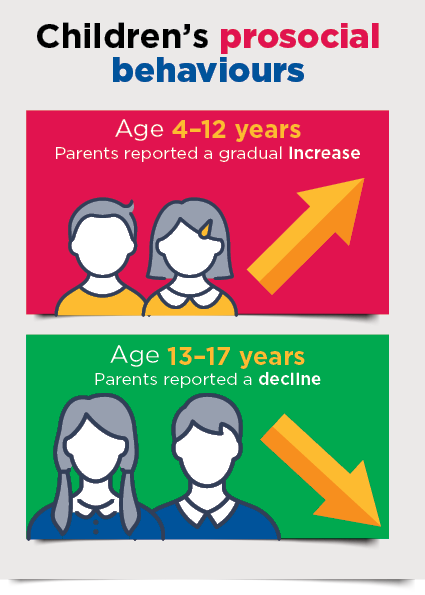

Children’s prosocial behaviours

Between the ages of 4 and 17, most children and young people engage in some form of prosocial behaviours. At least 80% of parents reported that their child showed prosocial behaviours between the ages of 4 and 17.1 This included helping another child if that person was hurt or upset, sharing with others and spontaneously volunteering to help others.

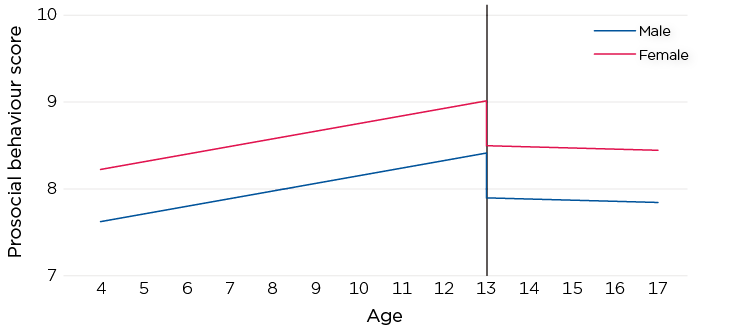

Prosocial behaviours (the total prosocial behaviour score) change with age (Figure 1). Parents reported their children’s inclination for prosocial behaviours gradually increased between the ages of 4 and 12 years. During the teenage years, parents report observing a decline in their children’s level of prosocial behaviours. Parents also report that after the decline at approximately age 13, prosocial behaviours remain low and stable between the ages of 14 and 17. The trend was similar for both males and females. However, parents of females reported higher levels of prosocial behaviours, compared with parents of males.

Figure 1: Children show more prosocial behaviours as they grow older but this declines in the teenage years.

Notes: Mixed effects model adjusted for child temperament, parental efficacy, parent feeling rushed, family cohesion and socio-economic position. ‘Prosocial behaviour score’ refers to the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) prosocial subscale score.

Source: LSAC B and K cohorts, Waves 1–8, unweighted

Change in children’s mental health between 4 and 17 years

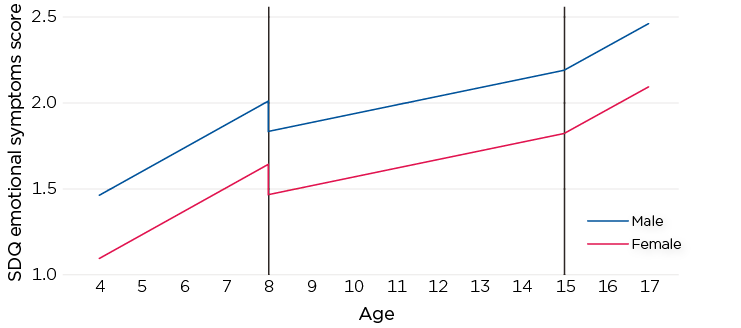

As children develop, poor mental health (a greater number of emotional symptoms) tends to increase. Emotional symptoms included parents reporting their child being worried, unhappy or downhearted, or clingy or easily scared. While most children may experience a slight decrease in symptoms at age 8, the mean level of emotional symptoms a parent reported their child experienced notably increased between the ages of 8 and 15 (Figure 2). Mental health trajectories were similar for males and females, although females were reported to have higher levels of emotional symptoms compared with males at every age.

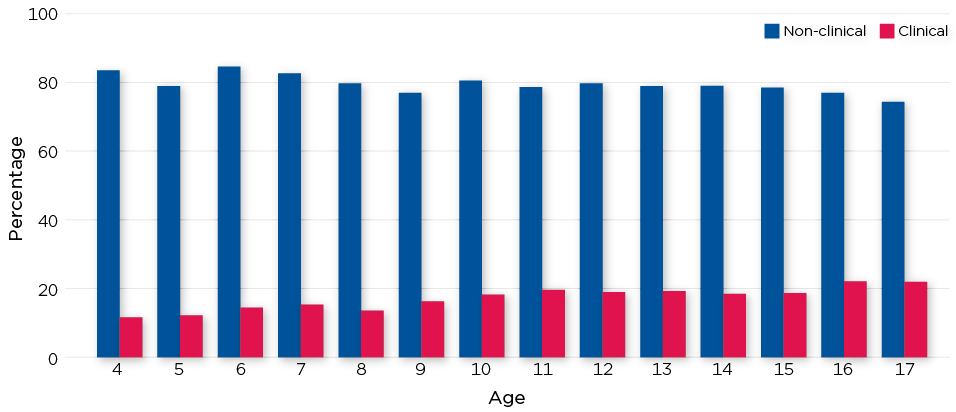

At age 4, approximately 12% of parents reported their children as showing ‘clinical levels’ (as defined by the SDQ categorisation) of emotional symptoms (Figure 3). The proportion of parents reporting ‘clinical levels’ of symptoms increased as children grew older, which is a pattern observed by other studies. By age 13, approximately 20% reported that their child demonstrated ‘clinical levels’ of emotional symptoms. This proportion increased to about 1 in 4 (23%) of children who were 17 years of age.

Figure 2: Overall, children’s poor mental health increases with age.

Notes: Mixed effects model adjusted for child temperament, parental efficacy, parent feeling rushed, family cohesion and socio-economic position. SDQ = Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Clinical levels of emotional symptoms are indicated by a score of 4 or higher on the SDQ emotional symptoms subscale (possible range 0–10).

Source: LSAC B and K cohorts, Waves 1–8. n = 8,173, unweighted

Figure 3: The proportion of children with ‘clinically’ poor mental health increases with age.

Source: LSAC B and K cohorts, Waves 1–8. n = 8,173, unweighted

Are prosocial behaviours associated with better mental health?

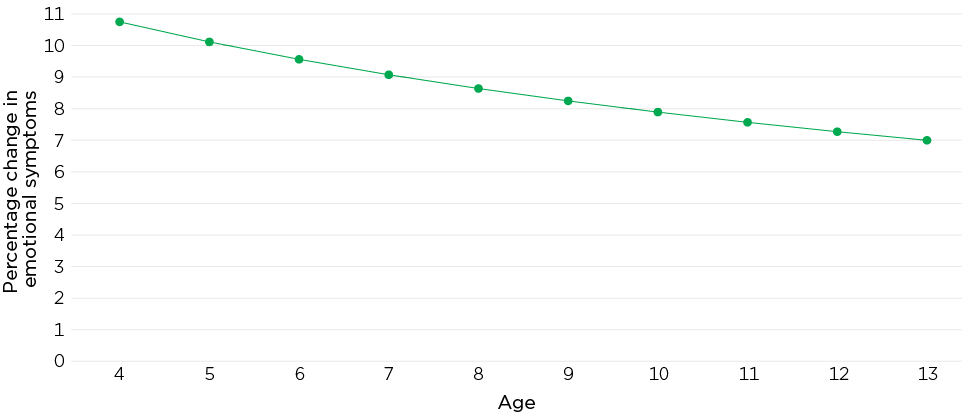

There is a strong and positive association between children engaging in prosocial behaviours and their level of reported emotional symptoms. Modelling indicated that in the pre-teenage years, if a child who is not showing prosocial behaviours develops more prosocial behaviours, this can significantly reduce their levels of emotional symptoms (Figure 4). However, this effect diminishes with age. At age 4, if a child with low prosocial behaviours develops more prosocial behaviours, emotional symptoms are reduced by an estimated 11%. At age 13, if a child becomes more prosocial, emotional symptoms can be reduced by approximately 7%. Results were similar for males and females. There was no association between prosocial behaviours and emotional symptoms between ages 14 and 17.

Figure 4: The benefit to mental health of developing a prosocial orientation declines as children age from 4 to 13 years.

Notes: Model prediction adjusts for underlying factors (e.g. parenting factors, SES and temperament).

Source: LSAC B and K cohorts, Waves 1–8. n = 8,096, unweighted

Does engagement in volunteering activities by age 12 benefit mental health during adolescence?

Although prosocial behaviours were not associated with mental health in the teenage years, participation in volunteering activities at this age is. By the age of 12, approximately 50% of children participate in at least one type of volunteering activity (Table 1). The predominant forms of volunteering for young people were with sporting clubs and their school. Controlling for a variety of factors (e.g. parenting factors, SES and temperament), we identified that if by age 13 a young person was involved in volunteering, the odds of having ‘clinical levels’ of emotional symptoms two years later were reduced by approximately 28%.2

| Any | Sport | School | Community | Church | Adventure | Culture* | Environment | Animal | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 49.7 | 18.2 | 14.3 | 12.6 | 9.1 | 10.3 | 3.9 | 3.6 | 2.0 | 9.8 |

| N | 3,064 | 1,125 | 879 | 777 | 560 | 635 | 239 | 221 | 121 | 606 |

Note: *Culture includes arts, heritage, cultural and musical volunteering activities.

Source: LSAC B cohort, Wave 7. n = 3,010, unweighted

Relevance for policy and practice

These findings show that prosocial behaviours and volunteering have psychological benefits for the person giving the care. The findings emphasise the importance of promoting and cultivating a prosocial orientation in childhood and early adolescence. The earlier a child under the age of 13 develops a prosocial orientation, the greater the positive impact on their mental health and wellbeing.

Given the sustained number of young people who are presenting with elevated mental health symptoms, teaching children to be prosocial and kind at an early age and providing them with opportunities to volunteer in civic and social settings may help to reduce the growing burden on the health system. There are a number of Australian-tested and effective (evidence-based) parenting and school and community programs (e.g. Triple P (PPP), Strengthening Families, You Can Do it and Friends for Life) that promote prosocial behaviours. These programs help parents, teachers and guardians to model, promote and reward prosocial behaviours. These programs have been evaluated through randomised control trials and are shown to improve the prosocial behaviours of parents, guardians, children and young people. These interventions can easily be delivered on scale across regions and communities. They could be made part of school curriculums, parent training interventions and community programs.

Potential of Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC)

Potential future research analysis could examine the following:

- Use linked data to examine the associations between prosocial behaviour and civic engagement with mental health service use.

- Examine associations of prosocial activities and civic engagement in childhood and adolescence with mental health and wellbeing in the adult years.

- Examine associations of prosocial behaviours with other wellbeing outcomes, such as optimism and resilience.

- Examine associations of prosocial behaviours with other important developmental outcomes such as educational performance.

Further details

Technical details of this research, including description of measures, detailed results and bibliography are available to download as a PDF [682 KB]

About the Growing Up in Australia snapshot series

Growing Up in Australia snapshots are brief and accessible summaries of policy-relevant research findings from Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC). View other Growing Up in Australia snapshots in this series.