Self-injury among adolescents

Self-injury among adolescents

Snapshot Series - Issue 4

Overview

AIFS recognises that each of the numbers reported here represents an individual. AIFS acknowledges the devastating effects suicide and self-injury can have on people, their families, friends and communities.

This snapshot discusses self-injury and presents material that some people may find distressing. If you or someone you know is feeling depressed or suicidal, please contact one of the following services:

In an emergency, call 000

Lifeline: 13 11 14

MensLine Australia: 1300 789 978

Kids Help Line (5-25 years): 1800 55 1800

QLife: 1800 184 527

Beyond Blue: 1800 512 348

Suicide Call Back Service: 1300 659 467

What do we know?

People who engage in non-suicidal self-injury deliberately hurt their bodies (e.g. by cutting or burning) as a way to manage intense emotional distress. Non-suicidal self-injury is a concern in young people as it often goes undetected. It is associated with long-term poor physical and mental health outcomes that extend into adulthood, and is also frequently linked to suicidality. Official statistics are likely to under-represent non-suicidal self-injury as they record hospitalised injuries only. Research suggests that population-level prevalence may be twice as high or higher than shown in national statistics.

What can we learn?

This snapshot explores the prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury (from here referred to as self-injury) thoughts and behaviours in Australian adolescents between 14 and 17 years, and how engagement in self-injury may change or persist in that time. It identifies socio-demographic, psychosocial, family and school factors across childhood that are associated with risk for engaging in self-injury. The following research questions are addressed: (1) How common are thoughts and acts of self-injury among young people in Australia? (2) Do young people who engage in self-injury continue to do so? What are the patterns over time? (3) What individual, family and school experiences or factors across the childhood life cycle put young people at higher or lower risk of engaging in self-injury?

Media release

Around one in three adolescents have considered self-injury

30 SEPTEMBER 2021

The study found that thirty percent of respondents had considered non-suicidal self-injury between the ages of 14 and 17, while 18% reported acts of self-injury.

News stories

In focus

The main outcomes of interest are the presence/absence of thoughts and acts of self-injury in the past 12 months as self-reported by LSAC study children at ages 14-15 (2014) and 16-17 (2016). 'Any self-injury' (self-injury at either time point) was used to examine factors associated with this behaviour. Factors included experiences from their early years (age 4-5, 2004), early adolescence (age 12-13, 2012), adolescence (age 14-15, 2014) and school experiences (age 14-15, 2014). Parents reported on their own and their children's wellbeing and parenting in the early years, and young people were asked about their relationships and mental wellbeing at age 14-15. School information and characteristics were taken from linked MySchool data.1

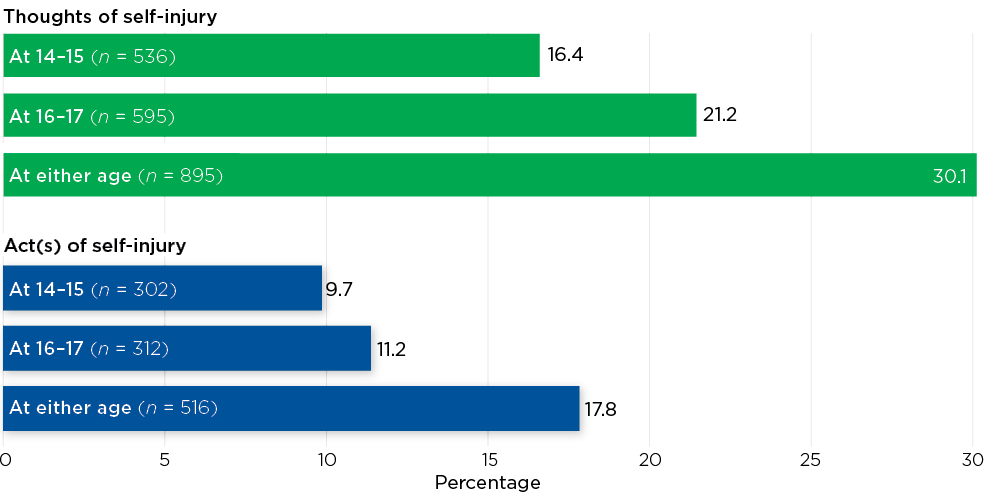

Prevalence of self-injury among young people aged 14-17

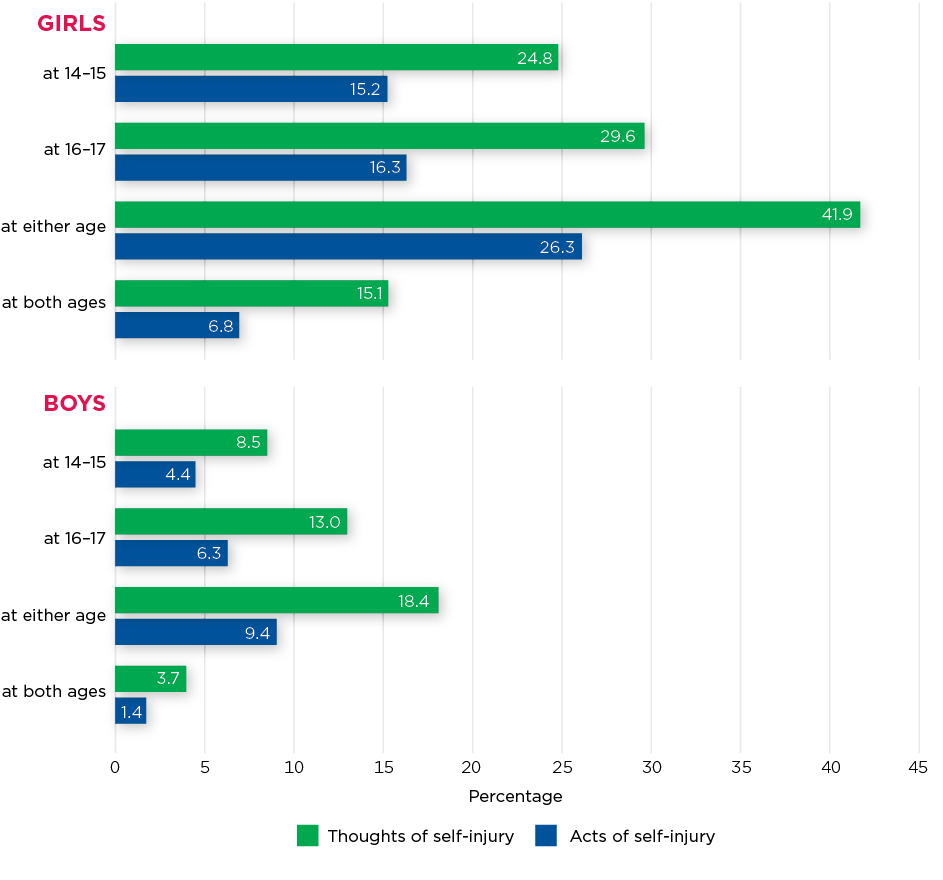

Between the ages of 14 and 17, approximately 30% adolescents had thoughts about self-injury and 18% reported an act(s) of self-injury. The proportion of both thoughts and behaviours increased from the ages 14-15 to 16-17 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Self-injury thoughts and behaviours from age 14-15 to 16-17

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 6-7, weighted. n = 3,319-3,321 at age 14-15 and 2,913-2,914 at age 16-17. At either age n = 2,790 for thoughts and n = 2,768 for acts.

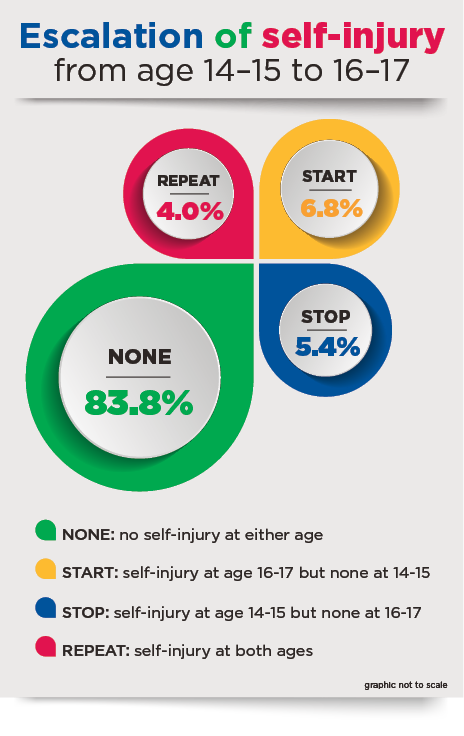

Self-injury patterns over time

The majority of young people did not report self-injury acts between the ages of 14 and 17. Five per cent reported self-injury at age 14-15 but not at age 16-17. Approximately 7% reported self-injury at age 16-17, and around 4% reported engaging in self-injury at both ages 14-15 and 16-17 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Escalation of self-injury from age 14-15 to 16-17

Notes: Categories were created using self-injury data from ages 14-15 and 16-17 to identify changes over time.

Source: LSAC K cohort, ages 14-15 and 16-17, weighted, total n = 2,724

Sex and other differences

Sex differences

Girls display higher rates of thoughts and acts of self-injury (Figure 3). Close to half (42%) of girls reported thinking about self-injuring at 14-15 or 16-17, compared to 18% of boys. Similarly, 26% of girls reported self-injury at either 14-15 or 16-17, compared to 9% of boys. Girls who had thought about hurting themselves at 14-15 were more likely than boys to go on to engage in acts of self-injury.2

Girls are also more likely to engage in repeated self-injury (Figure 3). Around 7% of girls reported self-injury at both ages 14-15 and 16-17, compared to 1% of boys.

Figure 3: Prevalence of self-injury at ages 14-15 and 16-17, by sex

Source: LSAC K cohort, ages 14-15 and 16-17, weighted. n = 1,390 to 1,695 for boys and n = 1,330 to 1,626 for girls

Other differences

Those who were same-sex attracted at age 14-15 (lesbian, gay or bisexual) were more likely to report having self-injured at some point between the ages of 14 and 17 compared to those who were not same-sex attracted (heterosexual, unsure or no attraction: 55% vs 15%). They were also more likely to engage in repeated self-injury (22% vs 3%, respectively).3

The impact of repeated self-injury

Repeated self-injuring is strongly associated with suicidal behaviour. Among LSAC participants, 65% of those who engaged in repeated self-injury reported attempting suicide at age 16-17.

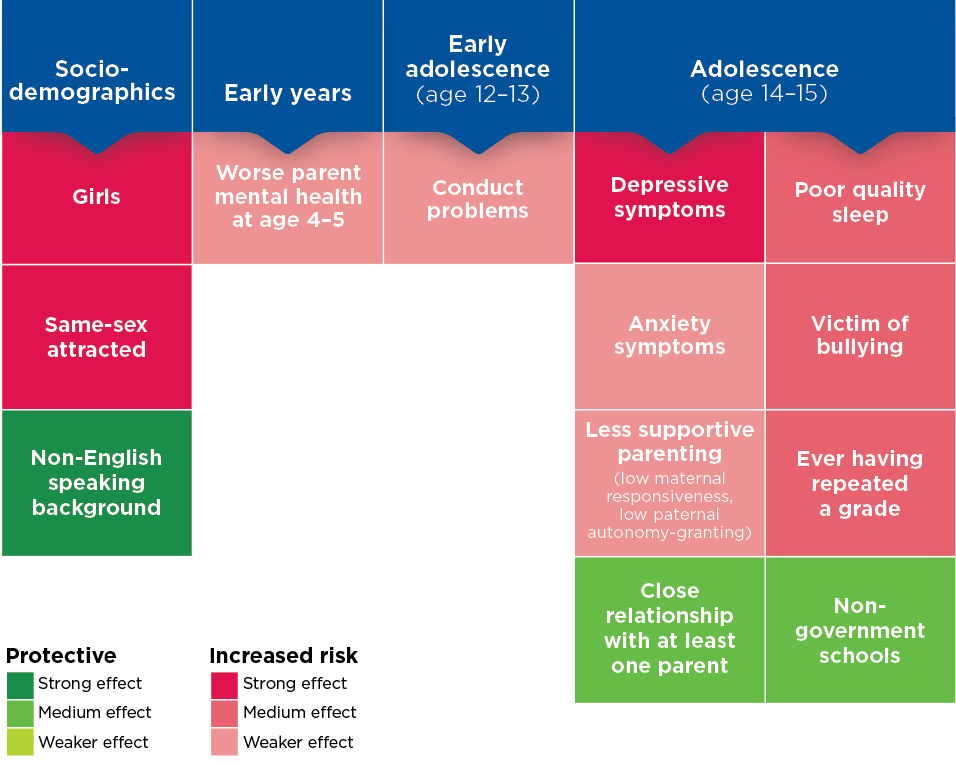

Childhood experiences associated with adolescent self-injury

A variety of factors during the childhood years between the ages of four and 15 - some modifiable - were examined for positive and negative associations with self-injury at ages 14-17 (Figure 4).4

Figure 4: Key risk factors across childhood associated with self-injury

Notes: Each box represents a significant predictor from the final multivariable logistic regression model predicting self-injury between ages 14 and 17. The logistic regression model adjusted for a range of factors including area of residence, emotional and peer problems, social functioning, school functioning, alcohol consumption, temperament, school size and peer relationships.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 1-7, unweighted, n = 2,504

| + increase in risk - decrease in risk | |

|---|---|

| + | Girls were twice as likely to report self-injury in adolescence compared to boys. |

| + | Young people who were same-sex attracted were much more likely to self-injure. |

| - | Children from non-English speaking backgrounds were half as likely to report self-injury. |

| Early years | |

| + | Poor parental mental health was associated with a higher risk of children reporting self-injury.5 |

| Adolescence (age 14-15) | |

| + | Having high symptoms of depression |

| + | Experiencing high anxiety |

| + | Sleeping poorly in the past month |

| + | Experiencing less supportive parenting (such as low responsiveness from mothers and low autonomy-granting from fathers) |

| - | having a close relationship with a parent |

| + | Having been the victim of bullying in the past year |

| + | Ever having repeated a school grade |

| - | Attending Catholic or independent/private secondary schools |

Relevance for policy and practice

Self-injury is prevalent among adolescents between the ages of 14 and 17, especially among girls. There are several family, school and community-based preventative options to consider:

- Family: Parents' mental health and parenting approach are cornerstones of children's development and wellbeing well into adulthood. The promotion of positive parental mental health and parenting practices from early childhood is a key avenue for supporting children and young people and reducing the risk of self-injury. This may include educating families to recognise signs of mental distress, particularly depression and self-injury, as well as supporting parents to know how to safely talk about mental health, self-injury and help-seeking.

- School: School is an important environment for young people, and peers and school health professionals are key supports. Building general mental health literacy among young people, in addition to supporting educators, is important for young people to know how and where to seek help for themselves and others. School health professionals can learn how to recognise signs of self-injury through training, and schools have a range of programs available to teach and promote mental health literacy and general wellbeing. Strategies to increase students' sense of belonging or connection with school are likely to increase the uptake and impact of these programs.

- Community: Where young people do report or demonstrate self-injury behaviour, it is vital that there is adequate treatment and follow-up. Avoiding repeated and persistent self-injury behaviours over time is critical to improve long-term outcomes and reduce overall rates of self-injury. The recent report by the Productivity Commission into Mental Health6 makes several recommendations for how this can be achieved and the role that individuals, schools and community and health services can play.

Potential of the Growing Up in Australia study

There are valuable insights that can be gained from LSAC in the future to build on this work, as more data waves become available and the cohort transitions into young adulthood. Future possibilities include:

- After the release of future data waves, there will be multiple waves of data on self-injury from ages 14-19 and beyond, allowing the exploration of long-term patterns of self-injury and suicidality from adolescence to early adulthood.

- Life course data could be used to assess risk factors for self-injury in particularly vulnerable subpopulations, and identify critical periods of intervention to prevent ongoing self-injury and the potential escalation to suicide attempts.

- Three waves of data (age 14-15, 16-17 and 18-19) will allow the examination of associations between thoughts and acts of self-injury, and progression into suicidal behaviour.

Further details

Technical details of this research, including description of measures, detailed results and bibliography are available to download as a PDF [123.52 KB]

About the Growing Up in Australia snapshot series

Growing Up in Australia snapshots are brief and accessible summaries of policy-relevant research findings from Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC). View other Growing Up in Australia snapshots in this series.

1 Full information on the data used is available in the supplementary materials.

2 More information is available in the supplementary materials.

3 More information is available in the supplementary materials.

4 Full information on regression models is available in Table S1 in the supplementary materials.

5 More information on early life experiences and childhood trajectory modelling is available in Figure S1 in the supplementary materials.

6 The Productivity Commission's report and recommendations can be found at: www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/mental-health/report

Acknowledgements

Authors: Sonia Terhaag and Pilar Rioseco

Series editors: Dr Bosco Rowland and Dr Tracy Evans-Whipp

Copy editor: Katharine Day

Graphic design: Lisa Carroll

This snapshot benefited from academic contributions from Dr Jennifer Prattley and Dr Tracy Evans-Whipp.

This research would not have been possible without the invaluable contributions of the Growing Up in Australia children and their families.

Website: growingupinaustralia.gov.au

Email: [email protected]

The study is a partnership between the Department of Social Services, the Australian Institute of Family Studies and the Australian Bureau of Statistics, and is advised by a consortium of leading Australian academics. Findings and views expressed in this publication are those of the individual authors and may not reflect those of the Australian Institute of Family Studies, the Department of Social Services or the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Featured image: © GettyImages/Tetiana Garkusha

Publication details

Terhaag, S., & Rioseco, P. (2021). Self-injury among adolescents (Growing Up in Australia Snapshot Series - Issue 4). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.