Young adults returning to live with parents during COVID-19

Young adults returning to live with parents during COVID-19

Snapshot Series - Issue 8

What do we know?

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, young adults in their late teens to mid-twenties have experienced significant disruptions to their studies, employment and social lives. These disruptions have occurred during an important phase of life when young people increasingly take on 'adult' roles and responsibilities and become more independent from their parents.

During times of uncertainty and stress, parents can provide economic, emotional and practical support to their children, which may help improve their resilience and ability to cope. In Australia, around a fifth of young adults have moved out of the family home by 21 years of age. Some of them return each year but this 'boomerang' phenomenon may have been exacerbated by the pandemic as young adults turned to parents for help and assistance. The COVID-19 pandemic may have significant implications for the future health, social and economic wellbeing of this age group.

What can we learn?

The experiences of young adults during the COVID period are not well understood. This snapshot reports on data from two national longitudinal studies of young people: Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) and the Longitudinal Surveys of Australian Youth (LSAY), that both surveyed 20-21 year olds in the first year of the pandemic in mid to late 2020. We examine the difficulties faced by young adults during the first national COVID-19 restrictions between March and May 2020 and young adult returns to the family home during the first year of the pandemic. This snapshot addresses four main questions: (1) What difficulties did young adults experience at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic (March-May 2020)? (2) Was there an increase in the number of young adults in Australia returning to live with their parent(s) during 2020? (3) What were the characteristics of young adults who returned to live with parents? (4) What supports were needed and obtained from parents?

In focus

This snapshot draws on the relative advantages of the LSAC and LSAY datasets. Both studies captured information from 20-year-old young adults in 2020. LSAC data provided nuanced information on difficulties experienced during the first COVID-19 restriction period and multi-dimensional measures of support, allowing us to describe young adult experiences and needs at that time. LSAY data comprised a larger sample and included information on residential status in 2019, making it informative for modelling young adult returns to living with parents. Further details follow.

LSAC: The normal sequencing and methodology of data collection for Growing Up in Australia was disrupted during 2020. Planned face-to-face interviews were replaced with a shortened questionnaire completed by study children (young adults) and their parents online. New questions were introduced to capture short-term impacts and experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. This wave of data collection (referred to as Wave 9C1) took place between October and December 2020 and achieved a lower participation rate compared to previous waves. There were 1,361 K cohort participants aged 20-21 years who completed the 9C1 survey (36% of the original eligible Wave 1/2004 sample and 45% of the Wave 8/2018 sample).

The young adults were asked to reflect back on circumstances experienced during the coronavirus restriction period (CRP). The CRP was defined as the period when governments first put in place restrictions and recommendations designed to curb the spread of COVID-19. For most Australians, this was between March and May 2020. The circumstances examined during the CRP were changes to household living arrangements including returning to live with parents, employment, study experiences, receipt of government benefits, difficulties due to the restrictions, social isolation and loneliness, and changes in the need for parent/family support.

LSAY: Data was used from the 2015 (Y15) cohort. Participants were aged 15 at commencement and data are drawn from Waves 5 and 6. Most Wave 5 interviews took place between August and December 2019 when participants were typically 19 years old. Wave 6 was administered between June and December 2020 when most respondents were 20 years old. The sample size at Wave 5 was 3,721 and 3,759 at Wave 6; both were approximately 36% of the original Wave 1/2015 sample. At Waves 5 and 6 young adults reported on whether they lived with parents and, in 2020, they were asked if any household move was due to government restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic. In Wave 6 young adults reported on their employment status at each month between March and June 2020. The sample was restricted to young adults with 'single' status in LSAY.

Difficulties experienced by young adults at the outset of COVID-19

The first national restriction period involved the closure of schools, universities and workplaces, limits on social gatherings and directives to stay at home. LSAC data suggest that young adults, especially females, experienced a range of difficulties at this time. We examined the extent to which they reported financial, social and emotional difficulties that may have been key drivers of their move to live with parents.1

Change in difficulties experienced over time

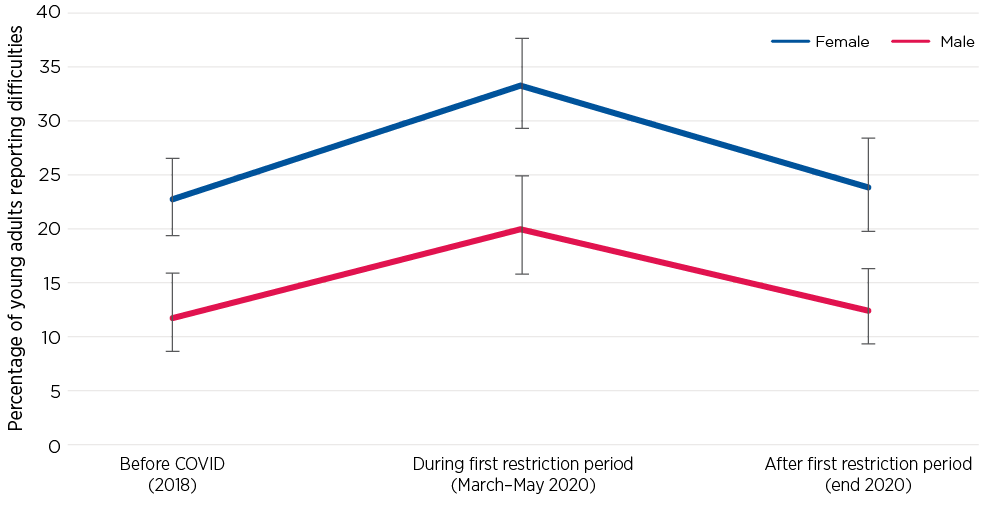

The proportion of young adult males and females reporting difficulties with life increased during the restriction period compared to before. Young adults in LSAC were asked a general question about the degree to which their life was difficult at three points in time: before the pandemic in 2018, retrospectively in 2020 for the restriction period and at the time of the survey in late 2020. More females than males reported 'many' or 'very many' difficulties in life at each time point. The proportion of males and females experiencing difficulties increased substantially during the restriction period, before falling back to pre-pandemic levels by late 2020 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Self-reported difficulties increased substantially in the first national COVID-19 restriction period (March-May 2020) but returned to pre-COVID levels at the end of 2020

Notes: Matched panel. 95% confidence intervals are shown by the 'I' bars at the end of each data point. Where confidence intervals for the data points being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the differences in values are statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Source: LSAC K cohort, Waves 8 and 9C1, weighted. n (males) = 489; n (females) = 686

Types of difficulties during the restriction period

Difficulties relating to COVID restrictions

Many young adults reported difficulties directly related to the restrictions. Overall, three-quarters (75%) of young adults found at least one aspect of the restrictions difficult.2 Females were more likely to report difficulties than males (84% reported at least one difficulty versus 64% of males).

Common difficulties related to missing people or events such as 'not seeing friends or family in person' (60% females and 47% males), 'missing important events' (65% females and 40% males), or to uncertainty about the future: 'not knowing how long the isolation would last' (56% females and 39% males). Difficulties relating to being confined to the home and family were less common: around one in three females (34%) and one in four males (23%) reported difficulty having to stay home and only one in five females (19%) and one in eight males (12%) had difficulty spending more time with family.

Loneliness and social isolation

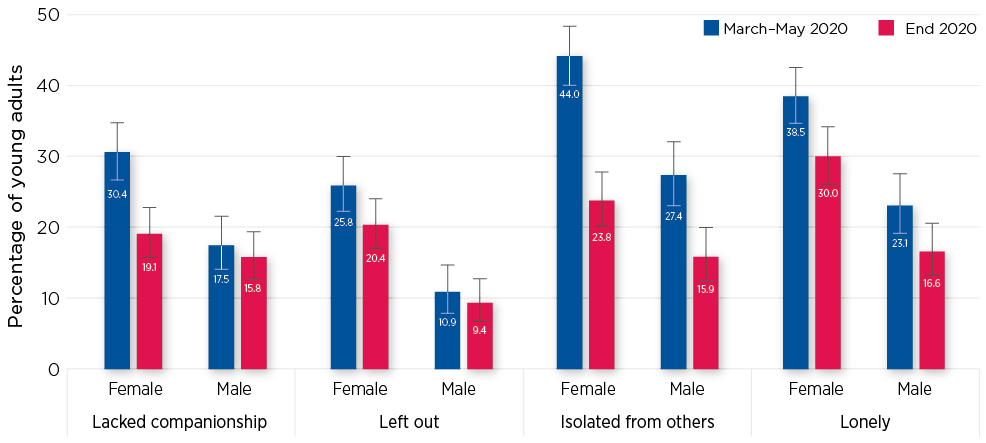

Unsurprisingly, more young adults reported being lonely and socially isolated during the restriction period compared to the end of 2020. A gender difference was observed, with more females than males reporting all four aspects of loneliness during restrictions. When reflecting back to the restriction period, 44% of females and 27% of males said that they had 'often' or 'always' felt isolated from others. At the end of 2020, these proportions had almost halved to 24% and 16% respectively (Figure 2).

For males, there was no change in the other loneliness measures (lacking companionship, feeling left out, and feeling lonely) between the restriction period and the end of 2020. In contrast, there were significant increases in the proportion of females lacking companionship and feeling lonely in the restriction period. The proportions of males and females feeling 'left out' did not differ between the two periods, most likely reflecting the universal nature of the restrictions, which meant young adults had little to miss out on.

Figure 2: Rates of loneliness and social isolation among young adult females were significantly higher in March-May 2020 (first national COVID-19 restriction period) compared to the end of 2020; less so for males

Notes: 95% confidence intervals are shown by the 'I' bars at the end of each bar. Where confidence intervals for the groups being compared do not overlap, this indicates that the differences in values are statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Source: LSAC K cohort, Wave 9C1, weighted. n (males) = 570-571; n (females) = 767-773 (The exact n varied according to missing data on study variables.)

Employment

Loss of employment or reduction in working hours during the restriction period were common. Over half (54%) of those who were in full- or part-time paid employment during the restriction period experienced a reduction in work hours and/or pay or lost their job.3 The most common impacts on employment were a reduction in hours worked (45%) and loss of work because their employer temporarily ceased business (21%). There were no statistically significant differences in employment impacts between males and females.

Financial stress

Approximately one in seven (14%) young adults reported difficulties in the past year (from late 2019 to late 2020) with meeting their necessary cost-of-living expenses such as housing, electricity, food, health care, clothing and transport. Despite no major differences in employment impacts between males and females, more females than males reported financial stress (18% vs 11%). Estimates of financial stress among 15-24 year olds from other sources indicate that the numbers experiencing financial stress in the pre-pandemic years (between 2008 and 2018) were lower at around one in 10 young people.4

Study difficulties and access to study resources

Many young adults who were in education experienced difficulties with their study during the restriction period. Over half (52%) reported low study motivation and 50% reported low concentration on their studies. High levels of study stress were reported by 47%.5 There were some differences by gender suggesting females had more difficulties: more females than males reported low concentration on their studies (56% vs 43%) and more males than females reported high study motivation (27% vs 17%).

The majority of young adult students (81%) had sufficient electronic devices for their needs but fewer always had reliable internet (61%) or sufficient space for their study and other needs (61%). Females were less likely than males to report having sufficient space for their study and other needs (55% vs 68% males).6

Young adults beginning to live with parents at the start of COVID-19

Data from both LSAC and LSAY suggest there was a substantial increase in the rate of boomerang returns to living with parents at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. LSAC data on all 20-21 year olds, regardless of who they were living with at the start of the pandemic, showed that 5% (an estimated 10,354 young adults) returned to live with their parent/s during the first restriction period, March-May 2020. The majority (91%) said that the move was because of the COVID-19 restrictions. More females returned to live with parents during the restriction period (34% vs 18% males), which may reflect gender differences in the age at which young adults tend to move out of home (more young adult females than males live away from their parents).7

These findings are complemented by data from LSAY, which allowed examination of the subgroup of young adults who were living away from their parents in 2019. In LSAY, 19% of 19-year-olds were living away from their parents prior to the pandemic in 2019.8 Fifty-nine per cent of these were female. LSAY data showed that 24% of young adults living away from their parents in 2019 (5% of all young adults) had moved home to parents in 2020 and 24% of these (5% of all young adults) moved home to parents between 2019 and 2020. Half of these young adults said the move was due to the restrictions imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic, implying that these moves occurred after March 2020 and that the rate was an increase over 'normal' rates of return. Among this group of young adults who were living away from parents in 2019, there was no difference between males and females in the rate of return to living with parents.

Data from other sources9 show that only around 1% of young Australians aged 18-21 returned to live with parents during the entire year of 2017 (approximately 1.1% males; 0.9% females), which is considerably fewer than observed in LSAC and LSAY for the 2020 period.

Characteristics of young adults who moved back home with parent(s)

According to LSAY data, there was no difference in the likelihood of returning to live with parents between males and females. Providing unpaid care (for parent(s), a child relative or a non-parental adult relative) and being a student were each related to moving back to live with parents.

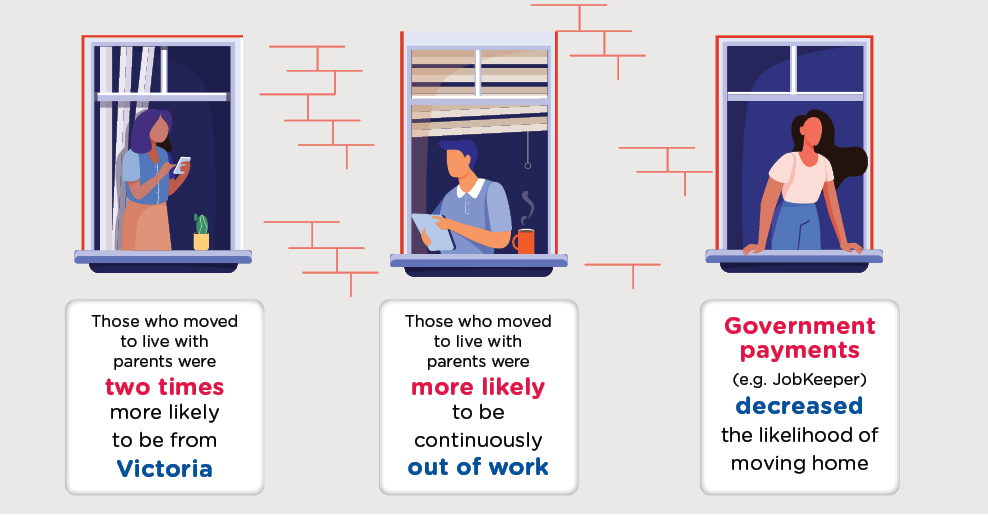

Those who moved to live with parents due to COVID-19 restrictions were two times more likely than those who didn't to be from Victoria (RRR = 2.0),10 where a second lengthy restriction period had taken place; to be continuously out of work during the first restriction period (RRR = 2.1); or to have left work during the first restriction period (RRR = 2.1). Government payments (e.g. JobKeeper) decreased the likelihood of moving home due to restrictions by an estimated 68% (RRR = 0.3). These factors were not related to moving to live with parents for reasons other than the COVID-19 restrictions.11

Supports needed by returning young adults

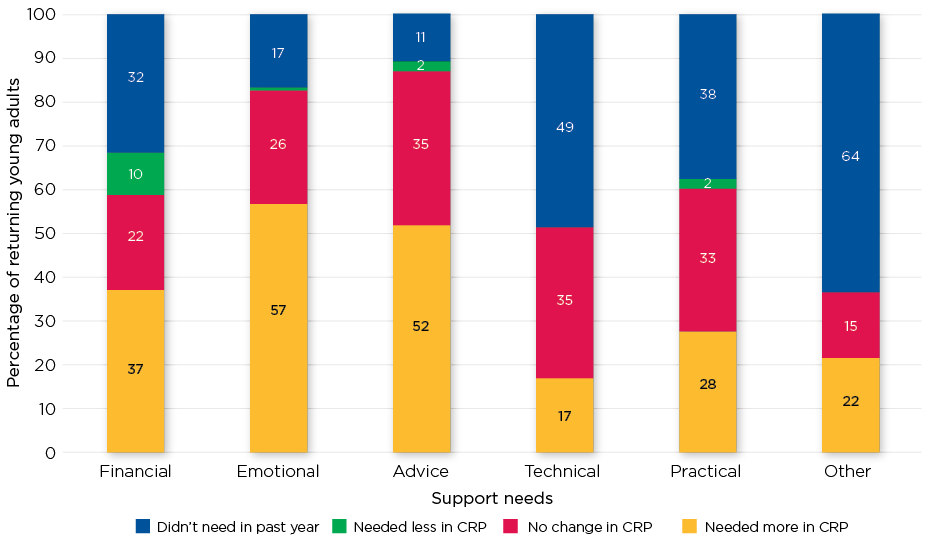

LSAC data were used to examine the support needs of young adults who returned to live with parents during the restriction period. The majority of returners needed more support from parents and family members since the start of the restrictions. Several types of support from parents or family were examined (Figure 3). Nearly all (89%) young adults who returned to live with parents needed advice from their parents in the past year. Emotional support (83%) and financial support (68%) were also commonly needed. For many young adults, the need for each of these increased during the restriction period. Compared to before the restrictions, more than half needed more emotional support (57%) and more advice (52%) and 37% needed more financial support. Overall, almost three-quarters (72%) of the young adults returning to live with parents had an increased need for at least one type of support during the restriction period. This was similar for males and females (67% and 73% respectively).12

One in 10 young adults who began to live with their parents needed less financial support during the restrictions compared to before. This group may include young adults who returned to live with parents at the start of the restriction period and who had a reduction in living costs (i.e. those who had already received financial support from their parents). In addition, some young adults in casual employment may have experienced greater certainty of income in the restriction period due to government financial assistance payments introduced in response to COVID-19.

Although generally positive, the experience of living with parents again was not easy for some young people. Of those who returned, 20% found having to spend more time with their family in the restriction period difficult and 11% reported that their parents had not met their needs for support since the start of the restriction period. These proportions did not differ between males and females.

Figure 3: The majority of young adults who returned to live with parents had increased needs for financial and emotional support and advice

Note: CRP = COVID-19 restriction period.

Source: LSAC K cohort, Wave 9C1, weighted. n (other) = 92, n (technical) = 100, n (practical) = 102, n (financial and emotional) = 103 and n (advice) = 105

Relevance for policy and practice

These findings reveal that young adults in Australia experienced significant challenges in many aspects of their lives during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. The snapshot shows that for most young adults, parents and families provided crucial support when the pandemic took away many of the normal scaffolding of supports they relied on, and there was a marked increase in the numbers of young adults returning to live with their parents. These young adults had especially high needs for emotional and financial support, which parents mostly provided. However, parent and family support was not available or sufficient in all cases. Two important messages arise from these findings:

- the need to consider young adults as an especially vulnerable group in policy responses to future national and international crises

- the need to monitor the ongoing health, social and economic wellbeing of the current generation of young adults who were so severely disrupted at the start of the pandemic.

Some specific recommendations:

- Ongoing monitoring of those young adults who returned to live with parents is important.

A minority who returned home reported a strain on family relationships or not having their needs met and may be at risk of deteriorating mental health. This may be especially apparent where young adults felt they had no alternative other than to return home and/or when cultural clashes between the generations occurred. In addition, living with parents in the longer term may result in disruptions to normal young adult transitions in education, career establishment, partnering and family formation. This may be particularly the case for young people who have moved to live with their parents in areas where social and employment opportunities are limited. - Young adults may require additional financial supports during the pandemic and in future crises.

Young people are often in more precarious employment (work with insecure and casual contracts and in industries most affected by the pandemic) and loss or reduction of paid employment during the restriction period was common. Although emergency government payments were found to be successful in reducing the financial impact on young people, some fell through the gaps: one in seven (14%) young people were unable to meet their necessary cost-of-living expenses. - Special attention should be directed to young adult females.

Females were more likely than males to report difficulties in the restriction period and female returners may have had different experiences living with their parents again due to established gender role norms. One example of this is that parents may have had higher expectations of females than of males to contribute to household and caring duties in the family. - Improved public health messaging targeted towards young adults may alleviate some of the difficulties relating to uncertainty about restrictions.

Although governments were responding to rapidly changing circumstances in the early phase of the pandemic, involving young people in developing messaging, possibly targeted specifically to females or males, during future crisis situations will be invaluable.

Potential of Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children

The COVID-19 restriction period disrupted traditional young adult milestones such as leaving the parental home, employment and study. The medium- and long-term social and economic impact of these disruptions can be monitored with ongoing follow-up of the LSAC sample. For example:

- Did young adults who remained living with parents for an extended period experience disruptions in their study, employment or social lives, or did the financial and emotional benefits lead to better future outcomes?

- What happened to young adult males and females who had difficulty living with parents again but had no option to change their household circumstances?

- What happened to young adults with unmet needs during the pandemic? Did they obtain support from sources other than parents such as government, charities, employers, education institutions or friends?

- How did living with young adult children again impact parents and other family members?

Further details

Technical details of this research, including description of measures, detailed results and bibliography are available to download as a PDF [204 KB]

About the Growing Up in Australia snapshot series

Growing Up in Australia snapshots are brief and accessible summaries of policy-relevant research findings from Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC). View other Growing Up in Australia snapshots in this series.

1 Difficulties were examined among all young adults, regardless of whether they were living with parents or elsewhere.

2 Full results are available in Table S1 of the supplementary materials.

3 Full results are available in Table S2 of the supplementary materials.

4 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2021). Material deprivation and financial stress. Canberra: AIHW. Retrieved from www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/material-deprivation-and-financia...

5 Full results are available in Table S3 of the supplementary materials.

6 Full results are available in Table S4 of the supplementary materials.

7 ABS census data from 2016 showed more young women aged 20-24 years than same-aged young men had moved out, thus making more eligible to return during the restriction period. See Australian Institute of Family Studies. (2019). Young people living with their parents. Retrieved from aifs.gov.au/facts-and-figures/young-people-living-their-parents. Results from the HILDA study suggest that this gender difference has reduced in recent years, see Vera-Toscano, E. (2019). Family formation and labour market performance of young adults. In R. Wilkins, I. Laß, P. Butterworth, & E. Vera-Toscano (Eds.), The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey: Selected Findings from Waves 1 to 17. Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic & Social Research, University of Melbourne.

8 Full results are available in Table S6 of the supplementary materials.

9 Vera-Toscano, E. (2019). Family formation and labour market performance of young adults. In R. Wilkins, I. Laß, P. Butterworth, & E. Vera-Toscano (Eds.), The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey: Selected Findings from Waves 1 to 17. Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic & Social Research, University of Melbourne.

10 RRR = relative risk ratio

11 Full results are available in Table S6 of the supplementary materials.

12 The small sample size did not allow for gender comparisons for each of the individual support dimensions.

Acknowledgements

Authors: Dr Tracy Evans-Whipp and Dr Jennifer Prattley

Series editors: Dr Tracy Evans-Whipp and Dr Bosco Rowland

Copy editor: Katharine Day

Graphic design: Lisa Carroll

This research would not have been possible without the invaluable contributions of the Growing Up in Australia children and their families.

Website: growingupinaustralia.gov.au

Email: [email protected]

The study is a partnership between the Department of Social Services and the Australian Institute of Family Studies, and is advised by a consortium of leading Australian academics. The Australian Bureau of Statistics were also partners of the study until 2022, with Roy Morgan joining at this point. Findings and views expressed in this publication are those of the individual authors and may not reflect those of the Australian Institute of Family Studies, the Department of Social Services, the Australian Bureau of Statistics or Roy Morgan.

About Growing Up in Australia

Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) is an ongoing national study that, at recruitment, was representative of all Australian children. It follows the lives of children and their families from all over Australia. In 2004, around 5,000 0–1 year olds (B cohort) and 5,000 4–5 year olds (K cohort) and their families were recruited and have been surveyed approximately every two years since. With extensive information on children's physical, socio-emotional, cognitive and behavioural development and linked biomarkers, education, health and welfare data, the study has been a unique resource providing evidence for policy makers to identify opportunities for early intervention and prevention strategies.

Other data source

Data from LSAC is complemented with data from the Longitudinal Surveys of Australian Youth (LSAY). LSAY focuses on the key transitions and pathways in the lives of young people, particularly the transitions from compulsory schooling to further education, training and the labour market. LSAY follows several cohorts of young Australians annually from their mid-teens to mid-twenties across a 10-year period. The LSAY samples are designed to be representative of 15-year-old Australian school students in the year they were recruited into the study. LSAY is managed by the National Centre for Vocational Education Research and conducted by Wallis Social Research on behalf of the Australian Government Department of Education.

Featured image: © GettyImages/Sladic

Publication details

Evans-Whipp, T., & Prattley, J. (2023). Young adults returning to live with parents during the COVID-19 pandemic (Growing Up in Australia Snapshot Series - Issue 8). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.